A top U.S. Navy official has laid out new details about the service’s vision for its future carrier air wings, including plans for the replacement of its F/A-18E/F Super Hornet multirole fighters. As well as a Super Hornet successor, which would be developed under the Navy’s Next Generation Air Dominance program, that same initiative is now also planning to replace the EA-18G Growler electronic attack jet, all part of reshaping a carrier air wing that could eventually feature as much as two-thirds unmanned aircraft. At the same time, the officer threw cold water on plans to add a new class of light aircraft carriers to the fleet.

While the Navy is working alongside the Air Force on some aspects of the respective Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) programs, the official said these are expected to result in different airframes and vehicles, but ones that will share some commonality in terms of avionics and subsystems. This suggests a platform-agnostic approach of the type that is a key feature of the Air Force NGAD program, a factor that The War Zone has discussed in the past.

The comments were made yesterday by Rear Admiral Gregory Harris, the director of the Air Warfare Division within the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. The official’s words shed some light on the otherwise murky US Navy iteration of the NGAD program, which is running in parallel to the U.S. Air Force’s own NGAD efforts, and aims to supersede the F-22 and even the F-35, at least to some degree. Last September, it was revealed that some kind of prototype related to the Air Force’s NGAD effort was already flying. The Navy, however, is still fleshing out the requirements for its NGAD initiative.

Like equivalent efforts in the Air Force, as well as in the United Kingdom and elsewhere in Europe, the Navy’s NGAD will be a “family of systems,” as Harris described it, with the F/A-XX as its centerpiece in the carrier air wing as the Super Hornet’s replacement. However, while Harris admitted that F/A-XX “may or may not be manned,” he also said it will “most likely be manned.” Beyond that, however, the overarching NGAD program will include a mix of manned aircraft and drones.

“We believe that as manned-unmanned teaming comes online, we will integrate those aspects of manned and unmanned teaming into that,” Harris added. However, the kinds of drones that NGAD is expected to yield may not be primarily intended to work alongside manned fighters. While the Air Force calls these types of combat drones loyal wingmen, Harris referred to them, informally, as “little buddies.” These drones could equally end up being used as adjuncts to electronic warfare or early warning platforms, as well as fighters.

The reference to early warning aircraft is especially notable. Harris went on to suggest that NGAD might also address a successor to the E-2 Hawkeye radar plane, noting that “We will have to replace the E-2D sometime in the future.” Now, it seems, an unmanned airborne early warning and control platform is a possibility, which would seem to align with U.S. Marine Corps plans in this field.

The Navy NGAD program now includes at least two distinct efforts, Harris confirmed. Increment one is to study replacements for the Super Hornet, which remains the tactical backbone of the carrier air wing, while increment two is focused on a successor to the Growler.

Increment two is also likely to take a family of systems approach, but Harris expects it will emerge as a combination of manned and unmanned systems. That suggests that while the attributes of a manned aircraft are acknowledged to be advantageous for the Super Hornet’s strike fighter role, the Growler’s mission set, which is primarily tasked with defeating hostile air defense systems would benefit from an unmanned platform, flying into harm’s way and perhaps incorporating stealthy and/or attritable design aspects. Meanwhile, the increasing focus on near-peer enemies outlined in the National Defense Strategy implies being prepared to take on the high-end air defense systems of China and Russia, for example. Attritable drones are, by their nature, comparatively low cost, ensuring that commanders are willing to use them in higher-risk scenarios from which they might not return.

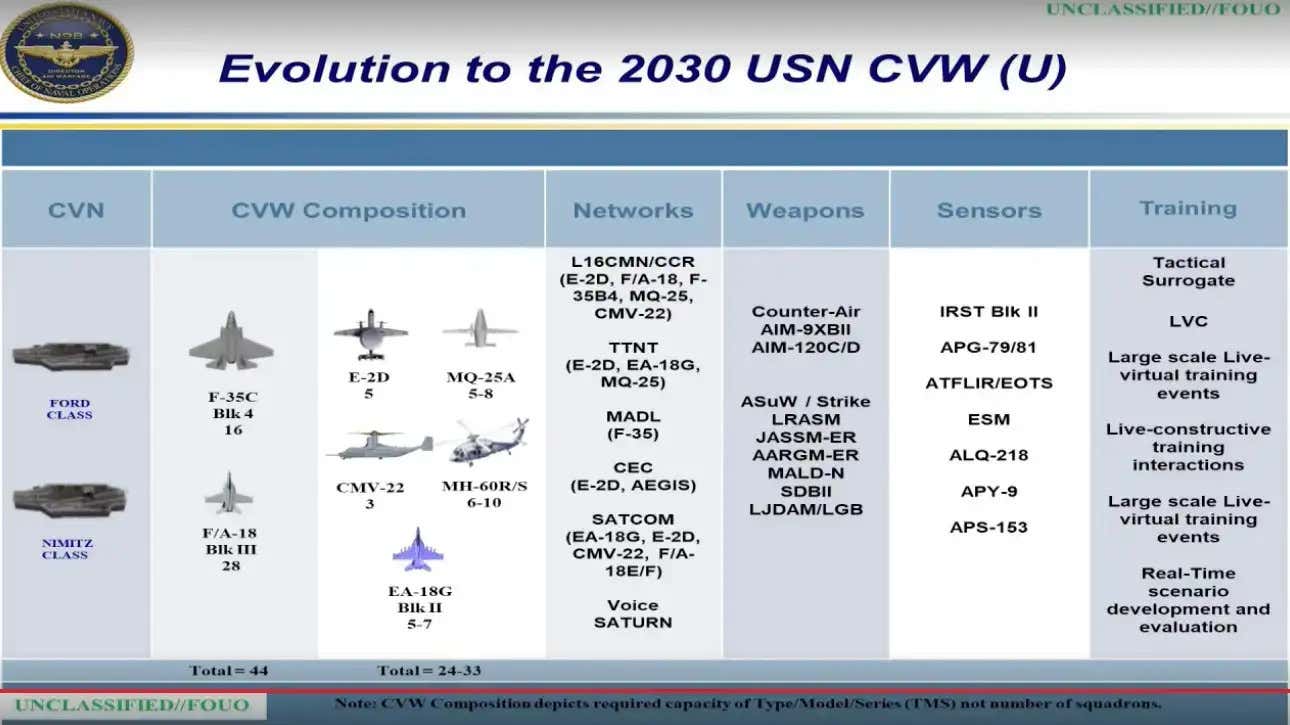

Overall, despite talk of a manned Super Hornet successor, the carrier air wing of the future is still likely to be dominated by unmanned platforms, Harris contended. He said the service is looking to move to a 40-60 unmanned-manned split, before transforming that to a 60-40 unmanned-manned split in the long term. Those aspirations make an interesting comparison with a depiction of a notional carrier air wing as of 2030 that the service has previously disclosed. As seen in the graphic below, in that previous concept, manned aircraft still vastly outnumber unmanned platforms in 2030, but that could still fit with the timeline for NGAD’s introduction.

Whether that manned/unmanned ambition plays out will depend heavily on the fortunes of the Navy’s MQ-25 Stingray tanker drone, which will be the Navy’s first operational, carrier-based unmanned aircraft. The MQ-25 will help prove concepts of operations, communication links, and more, that will help usher in more unmanned types into the carrier air wing.

There will very likely also be a role for the E-2D in the introduction of more drones to the carrier air wing. Earlier this month the Navy announced plans to modify the Advanced Hawkeye’s mission computer so it can also serve as a drone controller, as part of a manned-unmanned teaming experiment. That would allow off-ship command-and-control of the MQ-25, and potentially future drones, too.

Regarding the timeline on NGAD, and when it might actually yield new aircraft for the carrier air wing, tentative plans call for replacement of the Super Hornet and Growler beginning in the 2030s. That ambitious plan could also be another reason to favor a manned replacement for the F/A-18E/F since it represents less of a technological challenge compared to a multi-mission carrier-based fighter drone.

The aim of getting new platforms into service in the 2030s also puts a possible question mark over the status of the ongoing Super Hornet Block III and EA-18G Block II upgrade programs, which you can read more about here and here. The Super Hornet Block III upgrade, for example, which also includes a service life modification (SLM) effort, is projected to run through 2033.

In particular, Harris pointed to air-to-air combat as being a difficult hurdle for unmanned aircraft to master. He also referred to the challenges of introducing combat drones into existing rules of engagement, target verification, and battlespace awareness.

Currently, according to USNI reports, the Navy NGAD program is in the “concept refinement phase,” with the service working with industry to study available and emerging technologies, including in the unmanned realm. While Harris has tipped a manned successor to the Super Hornet as the most likely route, a final decision on this can be expected in two or three years, he said.

Whatever form the Super Hornet successor takes, it’s likely to offer more range than the F-35C, the carrier version of the Joint Strike Fighter stealth fighter that it will fly alongside. That aircraft has a combat radius of 700 nautical miles, while this is likely to increase to far beyond a thousand nautical miles via a new fighter. That would help in an Indo-Pacific scenario, for example, allowing the carrier to launch sorties while standing off far enough to be outside the heart of China’s anti-ship ballistic and cruise missile engagement envelope, as well as that of emerging hypersonic weapons.

Harris provided little in the way of detail about the types of drones that could form part of the NGAD family. However, he described the potential use of a missile-carrying drone ‘weapons truck’ as “not a step too far, too soon.” That would potentially enable a manned fighter, like the Super Hornet or its manned successor, to increase its available ‘magazine capacity,’ with a drone launching weapons at a target designated by the crew of the manned jet. Similar thinking is also behind a program called LongShot, led by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, in which contractors are crafting designs for an air-launched missile-toting air-to-air combat drone. In that concept, a larger manned aircraft would fire this unmanned air vehicle, which could then fly to a certain area and engage multiple aerial threats with its own weapons. This, in turn, would extend the range of the launch platform and reduce its vulnerability to hostile aircraft or air defenses, among many other benefits.

Harris also hinted at potentially adopting an approach somewhat similar to the Air Force’s ambitious ‘Digital Century Series,’ in which new technology is rapidly inserted into airframes, and even new fighter jet designs might be built at a rate of once every five years. Harris talked about open mission system architecture allowing new sensors to be added rapidly to platforms, avoiding the risks of “vendor lock” — when an established company has the entire responsibility for a particular system or set of systems. This can result in a platform being tied to a particular mission system that might be inferior and more costly than alternatives.

“We firmly believe that competition will give us a better reliability, lower sustainment costs, and lower the overall costs,” Harris added, before observing that he wanted to make more use of smaller companies to meet these aims.

While the idea of small-deck aircraft carriers has been entertained in recent years—by analysts, lawmakers, and naval officers alike—Harris made it clear that he sees the various NGAD assets operating from traditional nuclear-powered supercarriers, like the latest Ford class. In the past, the Navy has conducted studies into aviation-focused versions of the America class amphibious assault ships as well as a “light” derivative of the new Ford class, among others.

Harris said he doesn’t see a requirement for small carriers and that this requirement is already adequately filled by the Navy’s amphibious assault ships, which routinely embark U.S. Marine Corps short takeoff and vertical landing (STOVL) F-35Bs and AV-8Bs. Plans call for the latter type to have been entirely replaced by the F-35B by 2030. Meanwhile, the Marine Corps has also been looking at options for transforming existing amphibious assault ships into so-called “Lightning Carriers,” which would involve deploying between 16-20 F-35Bs.

Small-deck carriers, with conventional propulsion, would be cheaper than nuclear-powered carriers and potentially better able to project power in different parts of the globe as part of a more ‘distributed’ force posture. They would also be more flexible when it comes to deployability and less tied to programmatic maintenance. On the other hand, smaller carriers can be slower, have reduced and less capable air wings, and can’t carry as much fuel, weapons, and stores. They also are more dependent on underway replenishment.

While a formal Navy study into options for light aircraft carriers and future supercarrier designs is due next year, Harris said he was “confident that over the long run, we’ll find that there’s not a compelling return on investment to make a smaller carrier.”

Whatever route NGAD takes and whatever the makeup of the future carrier air wing, the plan to start fielding a successor to the Super Hornet and Growler in the 2030s, whether manned or unmanned, represents a significant challenge.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com