The Pentagon has announced that one of its offices has completed planned research and development work on a number of unmanned swarming technologies and has now turned them over to the U.S. Air Force, Army, Navy, and Marine Corps to support various follow-on programs. The systems in question are the Block 3 version of Raytheon’s Coyote unmanned aircraft and an associated launcher, a jam-resistant datalink, and a software package to enable the aforementioned drones to operate as an autonomous swarm. These developments give us a glimpse into what has been a fairly opaque, integrated development effort to field lower-end swarming drones across the services that leverages common components.

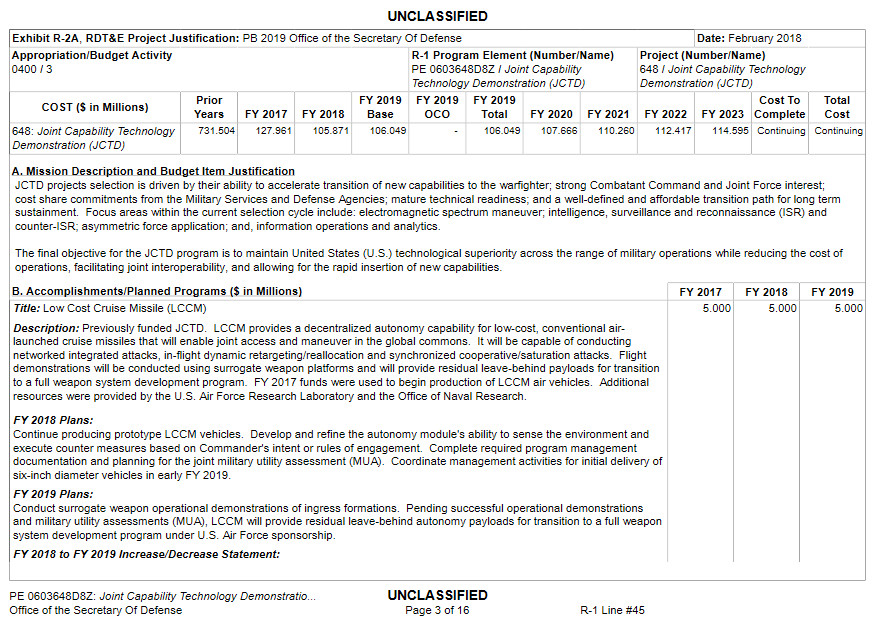

All of these technologies were developed under the auspices of the Low-Cost Cruise Missile (LCCM) effort, led by the Pentagon’s Joint Capability Technology Demonstration (JCTD) program office. The Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) and Office of Naval Research (ONR) were also directly involved in the project, which dates back at least to 2017. While Raytheon led the development of the Coyote and its launcher, L3Harris was the prime contractor for the datalink, and the Georgia Tech Research Institute at the Georgia Institute of Technology headed up work on the “autonomy software module.”

“This successful transition shows the great value of the JCTD program,” Jon Lazar, Acting Director of Prototypes and Experiments within the JCTD, who is also the head of the Rapid Reaction Technology Office within the Office of the Secretary of Defense, said in a statement released on March 16, 2021. “By working closely with our industry partners and combatant command operators, we delivered needed capabilities that will enhance the warfighter’s ability to accomplish their missions.”

Readily available details about the LCCM project are limited. It “provides a decentralized autonomy capability for low-cost, conventional air-launched cruise missiles that will enable joint access and maneuver in the global commons,” according to the Pentagon’s 2019 Fiscal Year budget request “It will be capable of conducting networked integrated attacks, in-flight dynamic retargeting/reallocation and synchronized cooperative/saturation attacks.”

“Flight demonstrations will be conducted using surrogate weapon platforms and will provide residual leave-behind payloads for transition to a full weapon system development program,” it continued. “FY 2017 funds were used to begin production of LCCM air vehicles.”

The press release regarding the transition of the technologies says that multiple “flight tests and operational demonstrations” were conducted at the U.S. Army’s Yuma Proving Ground in Arizona in 2018 and 2019. “In the final operational demonstration in 2020, multiple cruise missiles were pneumatically launched in a matter of minutes,” it adds.

“The swarm of LCCM vehicles then dynamically reacted to a prioritized threat environment while conducting collaborative target identification and allocation along with synchronized attacks,” the release continues. “The LCCM project also enabled significant improvement in understanding the relationship between communications and autonomy in collaborative vehicles.”

Given that the earlier budget document says that at least some testing would be conducted using “surrogate” systems, it’s unclear how much of this testing involved the Block 3 Coyote design, as well as the iterations of the datalink and autonomy software, which have now been transitioned to various branches of the U.S. military. It’s also worth noting that the exact configuration of that unmanned aircraft is unclear. The Block 2 type, which Raytheon publicly unveiled in 2018, has a completely different planform and propulsion system from the original Block 1, which first flew in 2007. You can read more about these two earlier versions, both of which can be configured to serve in a wide variety of roles, in this past War Zone piece. Calling any variant of the Coyote a “cruise missile” is certainly interesting in itself and highlights the often blurry distinction between certain unmanned aircraft designs and traditional missiles.

The Pentagon has only provided a few details about how the technology developed will now be leveraged Air Force, Army, Navy, and Marine Corps. For instance, the press release just said that the Block 3 Coyote would form “the baseline for numerous follow-on activities and programs within the Navy, Air Force, and Army.”

We do know what at least one of these other projects is thanks to a contracting announcement the Navy issued in February, which called for the acquisition of Block 3 Coyotes configured as loitering munitions, commonly known as “suicide drones,” that could operate in swarms after being launched from unmanned surface and undersea vehicles, or USVs and UUVs. You can read more about what we know about that project in this previous War Zone piece.

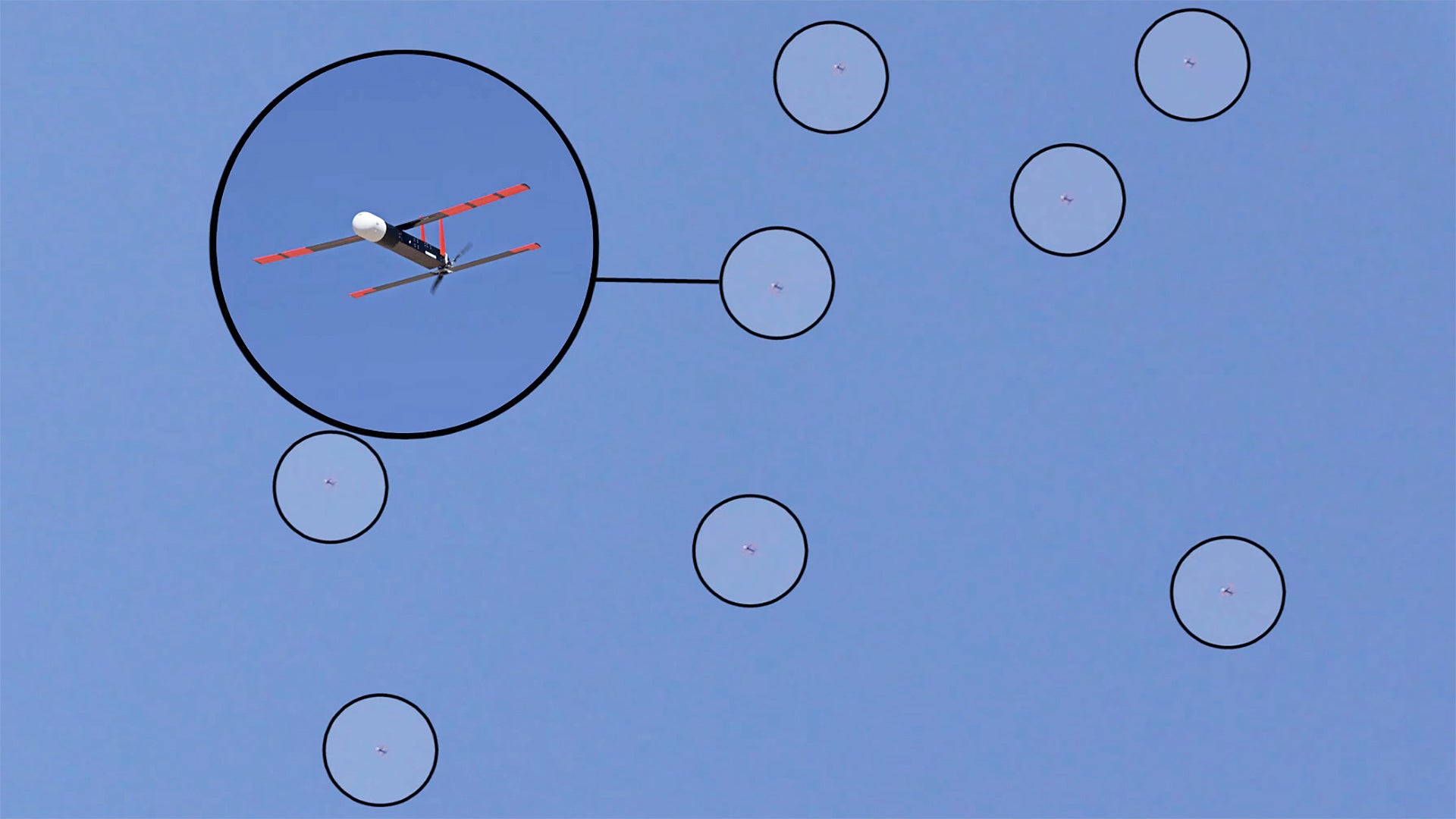

We also know that ONR has experimented with swarms of Block 1 Coyotes as part of its Low-Cost UAV Swarming Technology program, or LOCUST, and that the Air Force has also tested those drones, including in an air-launched environment from AC-130 gunships. In 2018, the Army also announced it would buy Block 2 Coyotes for use as counter-drone interceptors.

The video below of a LOCUST demonstration that ONR conducted in 2016 is the source for the image used at the top of this story.

The Pentagon’s description of the LCCM project also raises questions about its possible relation to other ONR efforts, including various “Super Swarm” experiments. Last year, that Navy office disclosed it had conducted a “record-setting effort [that] simultaneously launched 1,000 unmanned aerial vehicles out of a C-130 and demonstrated behaviors critical to future super swarm employment” known as the “Close-in Covert Autonomous Disposable Aircraft super swarm.”

Similarly, the Army is now looking to develop an entire family of air-launched swarming drones with various capabilities as part of its Air Launch Effects (ALE) program. Coyote Block 3, coupled with the other technologies developed under LCCM, certainly sounds like it could have the potential to meet many of the ALE requirements.

In 2017, the same year the Pentagon says work began to build actual air vehicles for the LCCM project, AFRL also initiated its own low-cost swarming cruise missile program, called Gray Wolf. That Air Force effort was canceled in 2019, with the focus shifting toward a related AFRL program, known as Golden Horde, which is developing technologies to enable various munitions to operate as networked swarms.

Golden Horde flight tests, which began late last year, have been demonstrating capabilities that sound virtually identical to the LCCM’s stated objectives of exploring “networked integrated attacks, in-flight dynamic retargeting/reallocation and synchronized cooperative/saturation attacks.” This is perhaps not surprising since the Pentagon says that this Air Force program will be one of the beneficiaries of the datalink and the autonomy module from the LCCM effort.

The datalink will also be used in “several spiral development programs,” according to the Pentagon. The autonomy software “will transition to the Marine Corps Long-Range Unmanned Surface Vehicle Program of Record and MITRE’s Simulation Experiments along with several Air Force and Navy spiral development programs,” the press release added.

In January, the Marines choose Louisiana-based shipbuilder Metal Shark to develop the Long-Range Unmanned Surface Vehicle (LRUSV), which the company described as a “tiered, scalable weapons system [that] will provide the ability to accurately track and destroy targets at range throughout the battle space,” in a press release. “While fully autonomous, the vessels may be optionally manned and they will carry multiple payloads, which they will be capable of autonomously launching and retrieving,” it continued, adding that loitering munitions would be part of the LRUSV’s arsenal. That specific element of the LRUSV effort sounds very similar in many respects to the Navy’s aforementioned plans to acquire Block 3 Coyotes configured as suicide drones for employment from other unmanned platforms.

It’s certainly no secret that the U.S. military, as a whole, is increasingly interested in unmanned swarming capabilities of various kinds, well beyond even the various programs mentioned already in this piece. Swarms, which are also gaining traction among military forces around the world, inherently have the ability to overwhelm, disorient, and confuse opponents. This makes swarms of drones particularly ideal for targeting enemy air defense networks, but they are just as applicable against other ground targets and in maritime environments, where they could potentially knock out the ability of warships to continue the fight.

Swarms also present novel ways to potentially reduce costs, since not every unmanned vehicle within one would have to be configured in the same way with the same capabilities. Certain platforms might be equipped with sensor packages to locate targets, while others could carry other payloads, such as electronic warfare packages or high-explosive warheads, to actually engage those threats. Advanced autonomous capabilities, supported by developments in artificial intelligence and machine learning, would enable the various elements of a swarm to apply their individual capabilities in the most effective manner and rapidly shift their focus to respond to pop-up threats and other changes in the battlespace.

All told, even from the limited information we have about this Pentagon project, it underscores the scope and scale of swarming programs across the rest of the U.S. military and looks to be an important link between many of them. A multitude of existing and future programs now look set to leverage the technologies developed under the LCCM effort as future unmanned swarms continue to take shape across the services.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com