The U.S. Air Force is looking to add new “cognitive” capabilities that leverage artificial intelligence, or AI, and machine learning, into electronic warfare systems now in development for various versions of the F-15, a concept known broadly as cognitive electronic warfare. Though the service has not identified any particular electronic warfare suites it is looking to improve in this way, the forthcoming Eagle Passive/Active Warning Survivability System, or EPAWSS, for its existing F-15E Strike Eagles and new F-15EXs would appear to be the most likely candidate. Cognitive electronic warfare, as a general concept, which you can read about more in this past War Zone piece, seeks to automate and otherwise speed up various aspects of electronic warfare, including the rapid development of new countermeasures, possibly in real-time.

The Air Force Life Cycle Manager Center (AFLCMC) at Wright Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio issued the contracting notice relating to adding cognitive electronic warfare capabilities onto F-15 variants on March 11, 2021. The F-15 Program Office is interested in “cognitive (artificial intelligence/machine learning) EW [electronic warfare] capabilities … that can be fielded in the next two years and incrementally improved upon and integrated into EW systems currently in development for the F-15,” according to that announcement.

This aligns well with the schedule, as we know it now, for the development and fielding of EPAWSS, which will eventually be standard on Air Force F-15E and F-15EX aircraft. Initial Operational Test and Evaluation (IOT&E) of EPAWSS is set to begin in 2023, which is then expected to lead to a decision about whether or not to begin full-rate production of those electronic warfare suites the following year.

EPAWSS is an all-digital self-protection system intended to replace the existing AN/ALQ-135 Tactical Electronic Warfare System (TEWS) found on the F-15E. While its exact capabilities are highly sensitive, we know that the new suite can detect, categorize, and geolocate various kinds of electromagnetic emissions, including those from hostile radars. It can then prioritize which ones present the biggest threats and then employ its jammers and other countermeasures against them.

“Providing both offensive and defensive electronic warfare options for the pilot and aircraft, EPAWSS offers fully integrated radar warning, geolocation, situational awareness, and self-protection solutions to detect and defeat surface and airborne threats in signal-dense contested and highly contested environments,” according to the manufacturer, BAE Systems.

EPAWSS “takes advantages of today’s computing, receiver and transmitter technologies to provide a quicker, smarter response to the threats and better actionable information to the pilot,” Ed Sabat, the Project Development Lead and Civilian Director of Operations at the 772nd Test Squadron, said about the system in 2020.

By every indication, EPAWSS already functions in a highly automated manner. This would make it ideally suited to the integration of cognitive electronic warfare capabilities.

“Cognitive electronic support and electronic attack technologies will investigate/resolve challenges of adaptive, agile, ambiguous, and out of library complex emitters that coexist with background (signals that are not the primary signal of interest) signal challenges,” the AFLCMC’s contracting notice said. “The government is also interested in cognitive technologies which provide rapid EW reprogramming capability or leverage the interplay and accumulation of knowledge for improved system performance.”

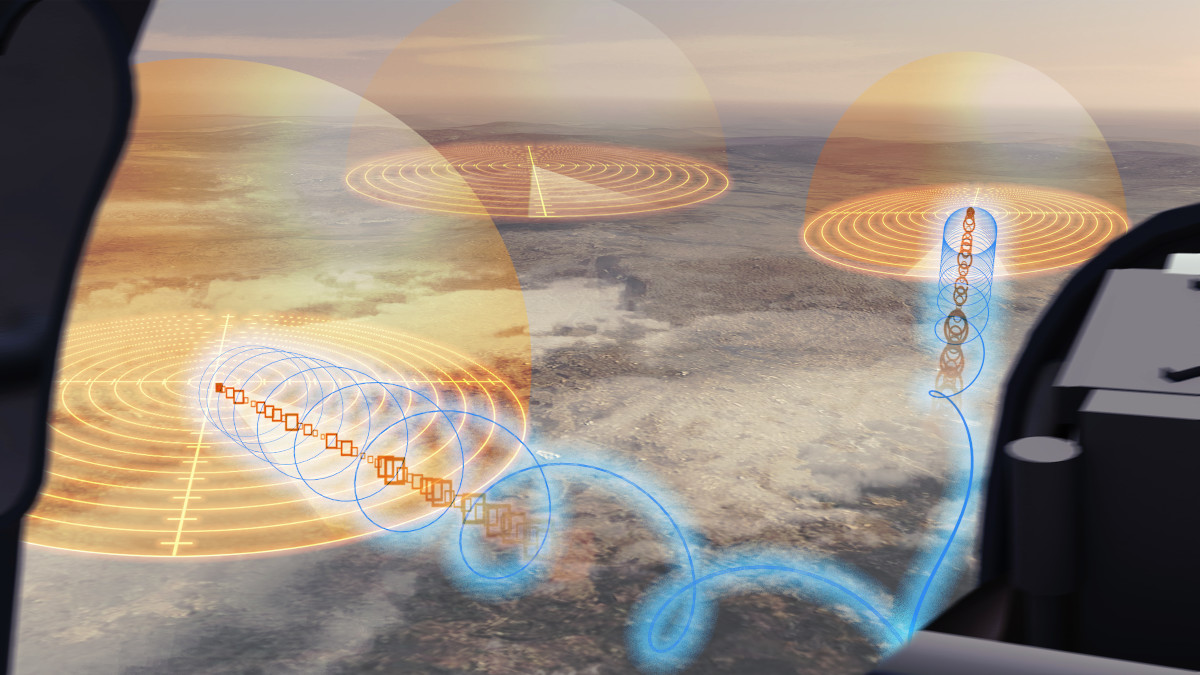

What this means in layman’s terms is that the Air Force wants to use AI and machine learning to enable electronic warfare systems, such EPAWSS, to be better able to perform its core functions even if the exact signals it picks up aren’t in its pre-programmed database or are being received in a confusing manner, possibly because they are being sent out in a new or unusual way or are just jumbled together with other more benign electromagnetic emissions. The idea is that advanced algorithms would be able to automatically respond, at least to some degree, to those challenges, working to at least categorize novel signals based on existing data or spot threatening ones in the clutter, all in real-time.

When it comes to aerial electronic warfare packages, the issue as it stands now is that they can only work with the information they have programmed inside them. This inherently presents the risk that they may be less effective when presented with previously unseen threats, such as a new radar, during any particular mission. Even after such a new enemy system is uncovered, intelligence analysts and engineers typically need a not-insignificant amount of time to gather information about it and then update existing countermeasures to be able to respond to it.

Cognitive electronic warfare presents a path to fundamentally change that process. The hope is that this technology will eventually allow for the ability to quickly transform any new information an electronic warfare system scoops up about previously unknown signals into all-new countermeasures or other capabilities. This is the “rapid EW reprogramming capability” that the AFLCMC contracting notice is talking about.

One early version of this capability could involve a suite like EPAWSS identifying novel signal data by itself, doing some initial analysis automatically, and then passing it along via various networks to personnel on the ground. Those individuals could then immediately begin to further analyze the information and, if necessary, start working out possible ways to respond to the new threats.

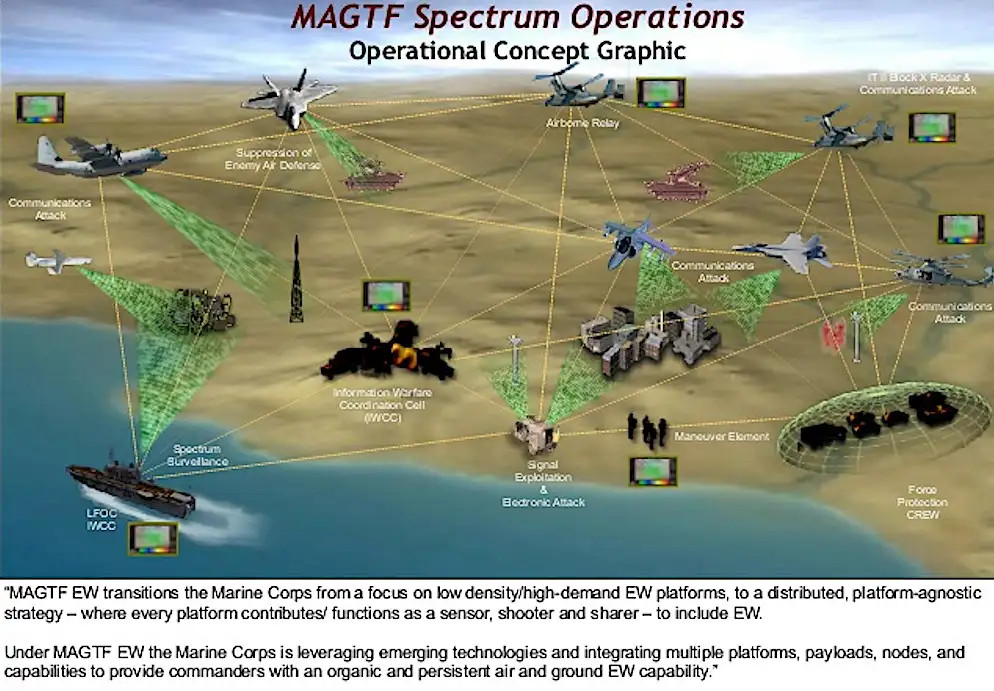

“In the near term, proven EW platforms within the land, maritime, air, and space domains would host cognitive EW capabilities as part of their detection and identification suite. Onboard these platforms organically collected and off-board feeds would provide spectrum domain awareness and emitter characterization to these platforms hosting cognitive EW toolkits,” Air Force Major John Casey wrote in an article discussing future cognitive electronic warfare concepts of operation last year. “Forward and remote operators aided by cognitive EW toolkits would scrutinize the EMS [electromagnetic spectrum] feeds off the sensors to rapidly characterize the spectrum and when necessary, immediately start the development [of] countermeasures.”

The absolute “holy grail” of this concept is electronic warfare suites that can do all of this internally by themselves in real-time. With regards to a system on an aircraft, this would mean that in the middle of a sortie, if an all-new electronic threat were to pop-up, the equipment onboard could immediately begin working on reprogramming its jammers to respond in the most effective way possible. With all this in mind, it’s very important to point out that the AFLCMC’s contracting announcement calls for technology that it could start to field now and then expand the capabilities as time goes on.

With regards to EPAWSS specifically, BAE Systems has already done some amount of work on cognitive electronic warfare capabilities as part of the separate Adaptive Radar Countermeasures (ARC) project, which the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) ran. “In Phase 2, we successfully demonstrated the ability to characterize and adaptively counter advanced threats in a closed-loop test environment,” Louis Trebaol, BAE’s ARC Program Manager, said in 2016 after the company received a contract to proceed to Phase 3 of that effort. “We will now continue to mature the technology and test it against the most advanced radars in the U.S. inventory in order to successfully transition this important technology to the warfighter.”

It is also worth noting that, in addition to the need to develop the kinds of algorithms to enable this kind of capability, this would demand significant processing power to work on any kind of truncated timetable. There is already separate work being done on the development of more compact computers that are still capable of high-volume processing, with a specific eye toward running AI-driven systems. The possibility of using networks to leverage off-board processing capacity for various purposes is something the Air Force, in cooperation with Lockheed Martin, is now exploring now, too.

In addition, there’s the definite possibility that the Air Force could look port whatever cognitive electronic warfare capabilities it acquires for use on its F-15s, which will be largely software-defined, into similar systems on other aircraft, so long as they have or can accommodate the necessary hardware. In the same vein, there’s the potential for any such development to support work on advanced electronic warfare systems designed for platforms other than aircraft and for roles outside of self-protection.

No matter what, the Air Force has laid out a clear desire to start giving all of its future F-15s these game-changing electronic warfare capabilities in the near-term.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com