The Marine Corps has begun a process that will see the inactivation of all units operating conventional helicopters in Hawaii by the end of next year. At least two relatively young AH-1Z Viper attack helicopters are reportedly in the process of being “decommissioned” as part of the plan. The decision to stop flying AH-1Zs, as well as CH-53E Super Stallions and UH-1Y Venoms, at Marine Corps Air Station Kaneohe Bay is a part of a broader, radical force structure redesign the service unveiled last year that also includes the elimination of its entire fleet of M1 Abrams main battle tanks, among other things.

Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS) Kaneohe Bay is slated to see the departure of 35 helicopters, in total, by the end of the 2022 Fiscal Year, as a result of the inactivation of Marine Light Attack Helicopter Squadron 367 (HMLA-367) and Marine Heavy Helicopter Squadron 463 (HMH-463), Marine Captain Colin Kennard, a spokesperson for III Marine Expeditionary Force (III MEF), told the Honolulu Star-Advertiser newspaper. HMLA-367 and HMH-463 are both presently assigned to Marine Aircraft Group 24 (MAG-24), part of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing. MAG-24 also has two squadrons flying MV-22B Osprey tilt-rotors, as well as one operating RQ-21 Blackjack drones.

“While the airframe-specific personnel and equipment associated with HMLA-367 and HMH-463 will depart, Marine Aircraft Group 24 will gain a KC-130 squadron in the years following the deactivations,” Captain Kennard explained to the Star-Advertiser. That additional squadron, plus increases in the personnel assigned to other units in Hawaii as part of the service’s larger restructuring plan, known as Force Design 2030, “will result in [total] manpower remaining relatively unchanged,” he added.

As many as 15 KC-130Js tanker-transports could eventually call MCAS Kaneohe Bay home, according to III MEF. In the meantime, the Marines have already started removing helicopters from the base.

Earlier this month, U.S. Air Force C-17A Globemaster III cargo planes flew two CH-53Es from Hawaii to join Marine units on the Japanese island of Okinawa. Two UH-1Ys have gone to Camp Pendleton in California.

Most notably, a pair of AH-1Zs “were sent to be decommissioned,” according to the Star-Advertiser. The exact disposition of those helicopters now is unclear. The last public inventory of aircraft at the U.S. military’s central boneyard at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona, which was released just today, does not list any Vipers among its holdings. We have already reached out to III MEF for future clarification.

However, if this refers to the impending retirement of these, and potentially more, AH-1Zs, that is a significant development. The Marine Corps only received the first of these helicopters in 2005 and the service declared it had reached initial operational capability with the type in 2011. HMLA-367 at Kaneohe Bay only received its first Vipers in December 2017, as it transitioned from the older AH-1W Super Cobra. The very last AH-1Ws were only retired for good last year.

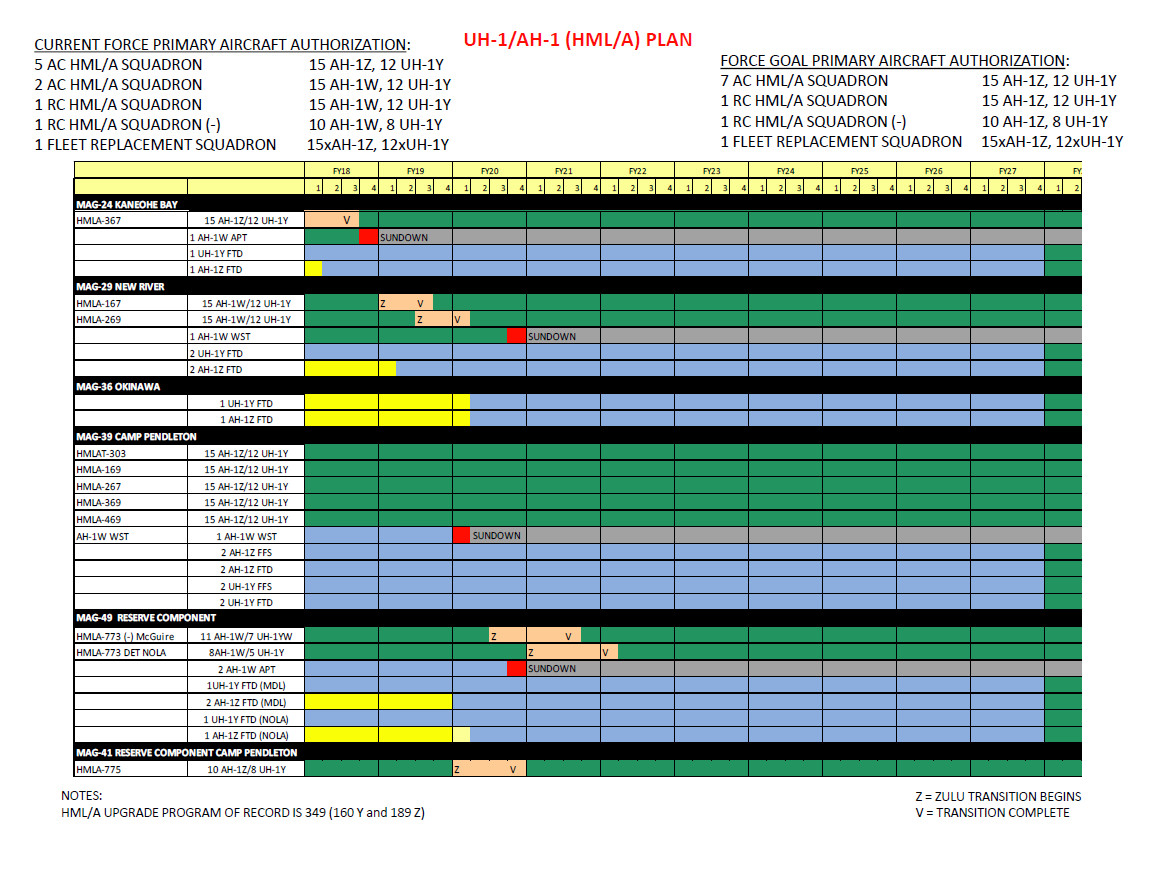

Note that, at least as of 2019, the Marine Corps did not yet have a clear projected out of service date for the AH-1Z, or the UH-1Y, though the CH-53E is slated to be supplanted by the new CH-53K King Stallion by the end of this decade. Marine light attack helicopter squadrons typically have 15 AH-1Zs, according to the 2019 Marine Aviation Plan. If HMLA-367 had that many Vipers initially and they are all bound for early retirement, that could mean the Marines are now looking at divesting some 10 percent of their entire AH-1Z force in the next year and a half or so, at least.

The Marine Corps primary argument for shuttering its conventional helicopter units in Hawaii is that the MV-22B’s speed and range, together with aerial refueling support from KC-130Js, which are now set to become organic to MAG-24, make the tilt-rotors better suited to operations across the broad expanses of the Pacific. “This capability has been utilized multiple times during Osprey trans-Pacific flights between Hawaii and Australia’s Northern Territory,” Captain Kennard, the III MEF spokesperson, told the Star-Advertiser.

In addition, the Marine Corps says that Force Design 2030, as a whole, including inactivating HMLA-367 and HMH-463, will help free up approximately $12 billion that it can then reinvest in various critical new capabilities, such as unmanned aircraft and long-range, ground-based anti-ship and land-attack missiles. New longer-range strike capabilities for the Marines are essential components of the service’s future concepts of operation that go along with restructured force. All of this is intended to enable distributed expeditionary operations utilizing smaller groups of more mobile Marines, especially in the Pacific region, where the main goal is to deter potential Chinese aggression, and then be better positioned to respond if an actual conflict erupts.

At the same time, the current plan would leave Marine Corps aviation elements in Hawaii with no organic platforms focused primarily on close air support and similar missions in support of forces on the ground. The AH-1Z has a three-barrel 20mm Gatling-type cannon in a turret in its nose and can carry various weapons, including AGM-114 Hellfire air-to-ground missiles, AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles, and rocket pods capable of firing 70mm Advanced Precision Kill Weapon System II (APKWS II) laser-guided rockets. The UH-1Y can also be armed with 70mm rocket pods, as well as door-mounted .50 caliber machine guns and 7.62mm Miniguns.

Efforts to arm the service’s MV-22Bs with more robust, forward-firing weapons have, so far, failed to translate into a widespread operational capability and there are only a limited number of roll-on/roll-off kits, known as Harvest Hawk, to turn KC-130Js into close air support aircraft. Of course, the Marines have already stated their position that the effort it takes to deploy AH-1Zs and UH-1Ys, as well as CH-53Es, from Kaneohe Bay inherently limits their utility.

Experts and observers have also raised concerns that the removal of all conventional helicopters from Hawaii will make it more difficult for Marine ground elements there to regularly train with those types, which they will still be expected to work with during future operations. “One of the hard things Gen. Berger has to do is make the hard calls today to ensure his Marines have the tools they need tomorrow, and I think this is one of those tradeoffs,” retired Marine Corps Lieutenant Colonel Frank Hoffman, now a Distinguished Research Fellow with the Institute for National Strategic Studies at the National Defense University and a member of the Board of advisors at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, told the Star-Advertiser.

The Marine Corps has already faced somewhat similar questions around its decision to eliminate its M1 tank force, even as calls elsewhere build for more heavy armored vehicles to ensure the U.S. military is prepared for a potential conflict with China in the Pacific. Last month, Lieutenant General Eric Smith, the Deputy Commandant for Combat Development and Integration, said that 4×4 Joint Light Tactical Vehicles armed with unspecified “lightweight” weapons had demonstrated an ability to engage enemy armor at ranges 15 to 20 times that of an Abrams tank, but provided no specifics regarding the exact parameters that went into that assessment.

“We can kill armor formations at longer ranges using additional and other resources without incurring a 74-ton challenge trying to get that to a shore, or to get it from the United States into the fight,” Smith said during an online talk put on during the International Armored Vehicles Conference. “You simply can’t be there in time.”

The Marine Corps clearly believes that hard choices, including the early retirement of at least some of its AH-1Zs, are necessary to realize the service’s new vision for how it will fight in the future. The end of Marine helicopter operations in Hawaii looks very much to be the beginning of a larger, significant transformation in the service’s aviation components.

UPDATE 3/16/21:

III MEF has confirmed that two of HMLA-367’s AH-1Zs, both of which were remanufactured AH-1Ws, were sent on their way to the boneyard at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base on March 12. It remains unclear how many AH-1Zs the Marine Corps may ultimately remove from service in the near term as a result of force structure changes stemming from Force Design 2030.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com