When one thinks of the U.S. Navy, ships, submarines, and fast fighter jets probably quickly spring to mind. Armored railcars probably not so much. Those sound more like the stuff of spaghetti westerns, WWII history books, and Steven Seagal movies. But after our investigation, spurred by rail spotters not being able to make sense of a mysterious blue-painted armored caboose, we learned that this year, the Navy, in cooperation with the Department of Energy, is set to begin using a new “fleet” of heavily armored cabooses specially outfitted to escort trainloads of sensitive nuclear material.

A reader of The Drive, Rafi Ward, first alerted us to pictures that have been circulating on social media of one of these mysterious cabooses, which has an alpha-numeric identification code, VWXX-800, a prefix that is known in the railroad world as a reporting mark. We subsequently acquired pictures of this car from photographer Anthony Delgado. Based on our own digging, The War Zone can now confirm that this railcar, and others like it, are being built under a U.S. government contract to support the Naval Nuclear Propulsion Program (NNPP), more commonly known simply as Naval Reactors.

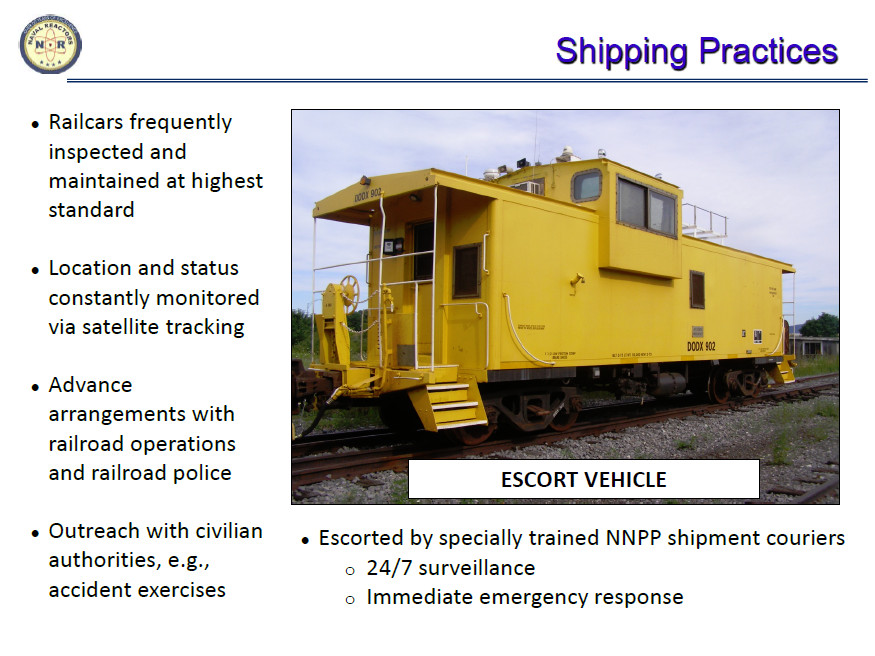

“The railcar series you describe (VWXX-800) is currently being built, outfitted, and certified by Vigor Works LLC under contract to the U.S. Government and will be used as a courier escort vehicle by the Naval Nuclear Propulsion Program to support spent nuclear fuel and other national security shipments,” a spokesperson for Naval Reactors told The War Zone. “The first railcar is expected to be delivered at the end of 2021 and placed into service shortly thereafter. The railcar replaces similar escort vehicles the Navy uses that are near the end of their service life.”

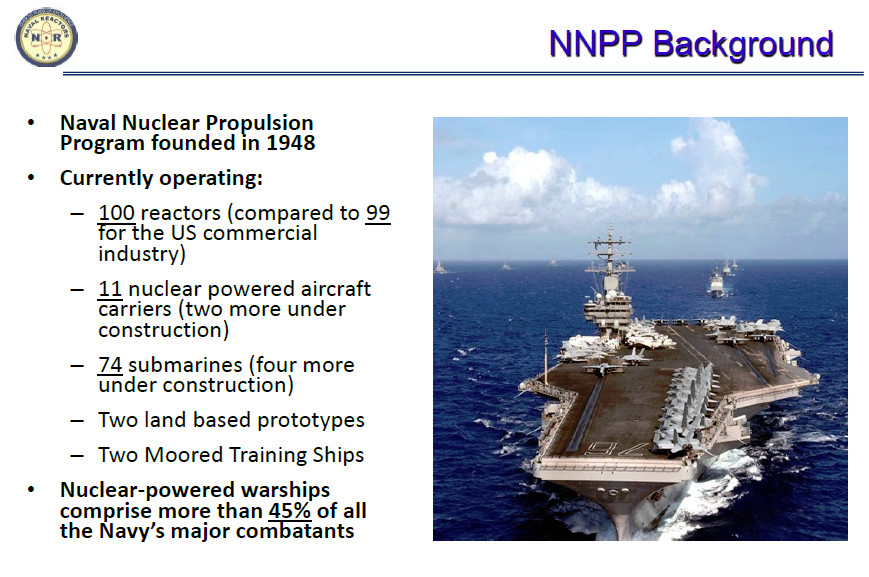

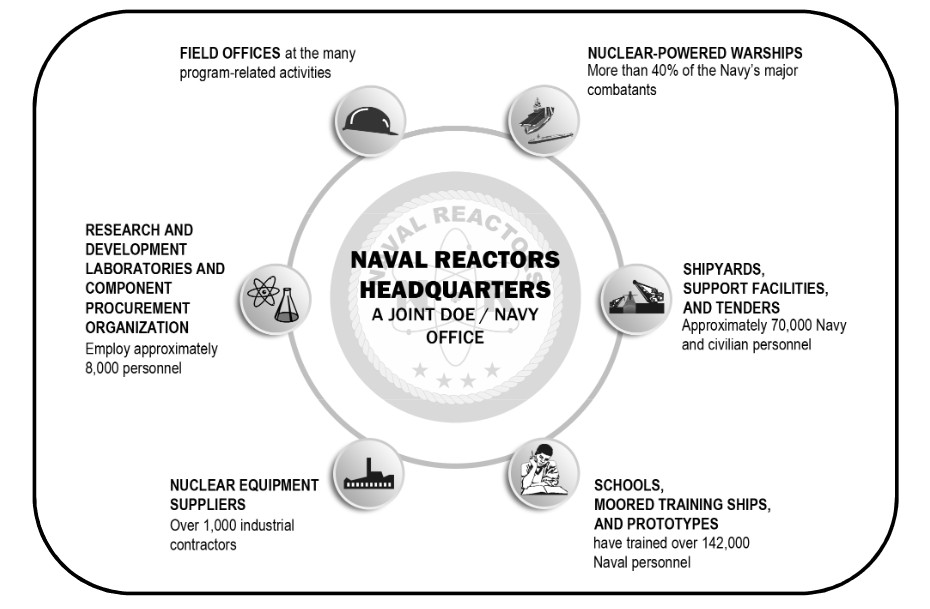

In its present form, Naval Reactors, which is responsible for the design, development, and sustainment of reactors for America’s nuclear-powered warships and submarines, as well as various associated work, is a joint Navy-Department of the Energy office led by a four-star admiral. Today, nuclear propulsion is used on America’s most important naval vessels, its aircraft carriers and submarines. This includes the Ohio class ballistic missile submarines that form one of the legs of the country’s nuclear deterrent triad, as well as the four Ohios converted to highly-specialized guided-missile boats. The successors to the Ohios, the forthcoming Columbia class, will also be nuclear-powered.

The Naval Nuclear Laboratory (NNL) is the main component of the NNPP and encompasses four separate facilities, the Bettis Atomic Power Laboratory in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; the Knolls Atomic Power Laboratory (KAPL) in Schenectady, New York; the Kenneth A. Kesselring Site in West Milton, New York; and the Naval Reactors Facility within the Idaho National Laboratory. Naval Reactors operates various other support and training sites and coordinates with naval shipyards and other industrial facilities.

The exact specifications of VWXX-800 are unclear. A spokesperson for Vigor Industrial confirmed that Vigor Works, a wholly-owned subsidiary previously known as Oregon Iron Works, had designed and built VWXX-800, but could not offer any additional details. They also did not say if any division of the company had previously built any similar kinds of specialized railcars in the past. A picture of this particular car is featured on the company’s nuclear products page.

Vigor Works is best known for designing and building a number of stealthy special operations boats for the Navy, which you can read about more in this past War Zone piece, but has also previously developed an unmanned seaplane for the Navy, built streetcars in cooperation with Czech firm Skoda, and crafted a buoy designed to test the possibility of turning waves into energy. Vigor Industrial also includes other large shipbuilding and marine repair enterprises that provide services to the Navy, among others.

An online database available through railroad company CSX says that VWXX-800 is just under 69 feet long, nearly 16 feet high at its tallest, and about 10 and a half feet wide. It has an unloaded weight of around 175,000 pounds and a maximum loaded weight of 185,000 pounds, per that same source. These weights are closer to the figures commonly associated with similarly cargo-carrying boxcars than cabooses, which are generally smaller all around.

Pictures show it has a typical caboose configuration, in general, with a cupola on top and access doors and the front and rear. There is also what may be a large door at least on one side of the car, which could allow personnel inside to rapidly disembark in an emergency or some other kind of contingency.

There are no traditional windows on the body of the car, but there are 10 windows with firing ports on the cupola, two each at the front and rear and six on each side. These would allow individuals to fire small arms at hostile individuals outside while remaining protected inside the railcar’s armored shell. What might appear at first glance to be additional firing ports on the body of the car look more likely to be floodlights, which would offer valuable illumination on either side during any incidents at night.

“The couriers escorting the Navy shipments are Federal Officers, provide constant surveillance, and act as first responders in the event of an issue with the transport,” the Naval Reactors spokesperson said.

The design appears to be substantially larger and more capable than the armored escort cabooses that the NNPP has now, which notably have no visible firing ports. It’s unclear how many of those escort railcars exist now, but a 2016 Naval Reactors presentation said that the plan, at least at that time, was to acquire five of the new examples from Vigor Works. It is certainly very possible that this represents a one-for-one replacement plan.

That same presentation said that the design work was 90% complete at that time and the NNPP would receive the first of the new escort cars for testing in January 2020. The procurement plan at that point was to buy two additional examples in both 2020 and 2021.

No matter the exact specifications of VWXX-800-series cars or exactly how they will be crewed and operated, having carloads full of armed federal officers accompanying any trains carrying nuclear material or other sensitive related items belonging to Naval Reactors between NNL sites, shipyards, and other facilities makes good sense. Even spent fuel rods and other nuclear waste could be attractive targets for thieves and other malign actors, including those looking to build so-called “dirty bombs.” A dirty bomb uses conventional explosives to disperse dangerous radioactive material. While experts debate just how real the threat from such a weapon might be, it certainly has the potential to spark mass panic, especially if detonated in a densely populated urban area.

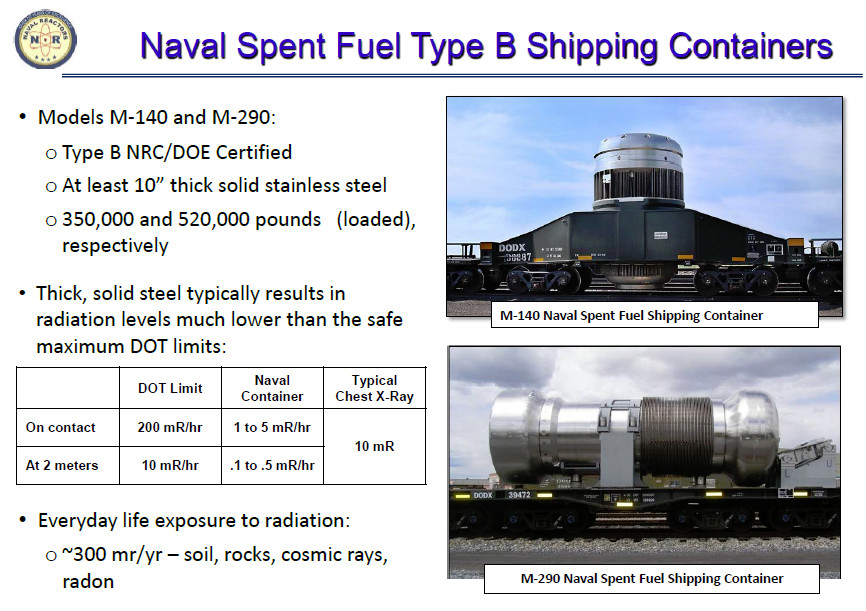

NNPP trains carry components in boxcars and, for larger items, in specialized shipping containers on flatcars. Two different types of sealed containers are used to transport spent nuclear fuel.

Trains carrying components typically include one flatcar or three to six boxcars, according to NNPP. Common routes for those trains run between facilities in New York and Virginia and shipyards on the East and West Coasts of the United States.

When it comes to spent fuel, those ships generally run from shipyards on the coasts to the Naval Reactors Facility in Idaho, where this waste is stored, at least temporarily.

It is somewhat interesting that Naval Reactors continues to use rail transport for its nuclear movements, at all. More than three decades ago, the Department of Energy end the practice of moving nuclear weapons via specialized trains, known variously as “atomic trains” or “white trains,” the latter referring to their initial plain white paint schemes.

“They featured multiple heavily armored boxcars sandwiched in between ‘turret cars,’ which protruded above the rest of the train. The turrets had slit windows through which armed DOE guards peered out, prepared to shoot if they needed to defend the train. Some guards had simple rifles, while others reportedly had automatic machine guns and hand-grenade launchers,” according to a 2018 piece from History.com. “Known in DOE [Department of Energy] parlance [as] ‘safe, secure railcars,’ or SSRs, the white trains were highly resistant to attack and unauthorized entry. They also offered ‘a high degree of cargo protection in event of fire or serious accident,’ the DOE assured a wary Congress in 1979.”

Protests and public outcry, driven in large part by growing opposition to nuclear weapons, in general, toward the end of the Cold War, prompted changing the paint scheme of the trains from white to various colors in the early 1980s. There were still concerns, both inside the U.S. government and out, as well as elsewhere around the world, about the safety and security surrounding these trains, the simple accidental derailment of which presented the potential risk of a major nuclear or radiological incident.

The video below shows a dramatic live test, dubbed Operation Smash Hit, that British Energy in the United Kingdom carried out in 1984 in an attempt to demonstrate the safety of transporting nuclear material via rail, even in the event of a derailment.

“The painting of these railcars will not stop dedicated protesters from identifying our special trains,” but “will make tracking our trains more difficult, and we believe, enhances the safety and security,” a 1984 Department of Energy memo said. By 1987, however, the decision had been made to bring the operation of these trains to a halt and replacement with specially modified tractor-trailer trucks loaded with James Bond-esque booby traps, which you read about in more detail in this previous War Zone story. These semis, a third generation of which is now under development, are also designed to be highly inconspicuous, but are not immune to detection or accidents themselves.

“The Department of Energy quit using railcars for weapon shipments in 1987,” a spokesperson for the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), which oversees America’s nuclear weapons stockpile, had confirmed was still the case to The War Zone as we sought information about VWXX-800. “Since then, DOE/NNSA has transported national security cargoes in highly modified secure tractor-trailers escorted by armed Federal Agents.”

Separate plans had also emerged in the 1980s to use discreet trains as mobile launch platforms for LGM-118A Peacekeeper intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM), a concept known as the Peacekeeper Rail Garrison, which would make it more difficult for the Soviet Union to target them. The Soviets had fielded their own train-based ICBMs and the Russians had looked to revive the idea in the mid-2010s, before shelving it again to focus on other higher-priority strategic weapons in 2017.

Specialized railcars to carry security personnel were to have been components of the Peacekeeper Rail Garrisons, as well. However, in 1991, with the end of the Cold War, the program was canceled. The LGM-118As instead ended up in traditional silos, before being removed from service entirely in 2005 as a result of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty II (START II) agreement.

It’s important to note, of course, that rail transport remains in use for the movement of commercial reactor components and nuclear waste. At the same time, reactors for naval vessels, in general, are significantly different from civilian power-generating types. Most notably, in part to help keep the reactors compact, but powerful, they often use weapons-grade highly enriched uranium (HEU). As of 2016, the Navy alone accounted for approximately 60 percent of HEU use in naval applications worldwide, according to the Arms Control Association. It’s worth pointing out that the head of Naval Reactors is also one of a number of Deputy Administrators at NNSA, underscoring both the importance and the sensitivity of the NNPP.

Naval Reactors’ position is that the exact construction of the fuel used in the Navy’s reactors makes it very safe, by fissile material standards, when it comes to accidents. The fuel rods are solid metal with the nuclear material being fully encapsulated inside, a design decision already driven by the need to make it safe for sailors to work around them on a regular basis and to ensure they are resistant to battle damage during actual combat. “Naval fuel is built to withstand combat battle shock forces well in excess of 50 times the force of gravity (more than 100 times the force of a severe earthquake),” an NNPP document from 2017 says.

Still, there have been efforts to reduce the use of HEU in the Navy’s reactors for safety and security reasons, but this has faced opposition over the years from various ends of the U.S. government. Plans to shift naval nuclear propulsion to primarily use non-weapons-grade low enriched uranium (LEU) are, at best, decades away from becoming a reality.

Regardless, at least in the meantime, Naval Reactors will continue to use rail as a means to transport nuclear and nuclear-related cargoes around the country. If the Navy keeps to its schedule, VWXX-800 will be in service helping to guard those trains by the end of this year.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com