The Pentagon has submitted a plan to Congress outlining more than $27 billion in proposed spending over the next six years to bolster capabilities across the Pacific region to deter China. This expansion of what is now known as the Pacific Deterrence Initiative, or PDI, would most importantly include the establishment of forward-deployed long-range strike capabilities, including elements that could be armed ground-based cruise, ballistic, and hypersonic missiles. In addition, the plan is to add more capable missile defenses, as well as new space-based and terrestrial sensors, and find ways to ensure access to airfields, ports, and other facilities needed to support these efforts and other future distributed operations.

Breaking Defense was among the first to report on these future plans for the PDI, with other outlets subsequently reporting additional details. Congress approved the creation of the PDI in the annual defense policy bill, or National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), for the 2021 Fiscal Year, which was passed over former President Donald Trump’s veto in January. This initiative, in broad strokes, is meant to mirror the European Defense Initiative (EDI), which was established to deter Russian aggression following the Kremlin’s invasion and subsequent annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea region in 2014.

“The greatest danger to the future of the United States continues to be an erosion of conventional deterrence,” one of the PDI documents submitted to Congress said, according to Japanese outlet Nikkei Asia. “Without a valid and convincing conventional deterrent, China is emboldened to take action in the region and globally to supplant U.S. interests. As the Indo-Pacific’s military balance becomes more unfavorable, the U.S. accumulates additional risk that may embolden adversaries to unilaterally attempt to change the status quo.”

The Fiscal Year 2021 NDAA had included plans to spend approximately $6.9 billion on the PDI through Fiscal Year 2022. Indo-Pacific Command (INDOPACOM) had previously supplied lawmakers with a proposal to spend $20 billion, in total, by the end of Fiscal Year 2026.

The new plan the Pentagon has now prepared for legislators lays out between $27.3 billion and $27.4 billion in total spend through the Fiscal Year 2027. This includes $2.2 billion to be spent in the 2021 Fiscal Year and another $4.6 billion expected to be available in the next fiscal cycle.

From what we know so far, the specific items that INDOPACOM wants in the coming years include:

- $3.3 billion for “highly survivable, precision-strike fires can support the air and maritime maneuver from distances greater than 500 km [kilometers; ~310 miles]” in the Western Pacific.

- $1.6 billion to establish an Aegis Ashore missile defense site on the U.S. island territory of Guam.

- $2.3 billion to launch “a constellation of space-based radars with rapid revisit rates.”

- $197 million to build a “Tactical Multi-Mission Over-the-Horizon Radar” capable of detecting air and surface threats in the archipelago nation of Palau.

- $206 million for “specialized manned aircraft to provide discrete, multi-source intelligence collection requirements.”

- $4.67 billion for “Power Projection, Dispersal, and Training Facilities” within the United States, to include its territories, as well as Micronesia, Palau, and the Marshall Islands, which are sovereign nations that are heavily tied to the United States via an international agreement known as the Compacts of Free Association (COFA).

Though specific details are extremely limited, the plans to establish new forward-deployed long-range precision-strike capabilities are certainly one of the most notable aspects of the proposed PDI spending layout. No specific weapons or deployment locations are mentioned, but it is clear that the goal is to put land-based systems relatively close to the Chinese mainland and other strategic areas in the Western Pacific.

The United States “requires highly survivable, precision-strike networks along the First Island Chain, featuring increased quantities of ground-based weapons,” one of the PDI documents sent to Congress said. “These networks must be operationally decentralized and geographically distributed along the western Pacific archipelagos using Service agnostic infrastructure.”

The term “first island chain” refers to an area of the Pacific inside a boundary formed by the first line of archipelagos out from mainland East Asia. This broad zone includes the hotly contested South China Sea, as well as the highly strategic Taiwan Strait. Strategic planning in the Pacific also often takes into account needs within a region defined by a “second island chain,” the boundary of which stretches between Japan and eastern Indonesia and includes the U.S. territory of Guam.

The U.S. military, as a whole, and the U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps, especially, are actively developing various land-based long-range land-attack and anti-ship missile capabilities, to include new ground-launched cruise missiles, ballistic missiles, and hypersonic weapons, all of which could be potentially forward deployed in the Western Pacific to complement air and sea-launched systems. The U.S. military, and the U.S. Army, in particular, has been talking for some time now about plans to base some of these future missiles on islands in the Western Pacific as part of a strategy to deter China. Having these types of weapons positioned closer to the Chinese mainland could present a very different kind of deterrent threat.

However, reports have already emerged that many American allies and partners in the Pacific, such as Australia and South Korea, do not appear to be overly inclined to offer to host any of these weapons. A senior Japanese Foreign Ministry official did tell Nikkei Asia that the planned American missile force in the Pacific “could be discussed as we talk about the course of the Japan-U.S. alliance” and another Japanese official also told that out that this “would be a plus for Japan.” At the same time, neither of those statements voice any sort of clear support for the country actually hosting the U.S. weapons itself.

The video below shows a test of a ground-based Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile in 2019. Tomahawk is one of the weapons that is being considered for adaptation for use in a land-based role in the Pacific.

In contrast to the long-range strike component of the PDI proposal, the plans to build the Aegis Ashore site on Guam, also being referred to as the Guam Defense System, by 2026 have become much more defined since they first emerged last year. U.S. Navy Admiral Phil Davidson, head of INDOPACOM, has said that this is his number one priority for the region. This facility would provide a more robust forward-deployed missile defense node in the Western Pacific offering “integrated air missile defense in the second island chain,” according to one of the PDI documents.

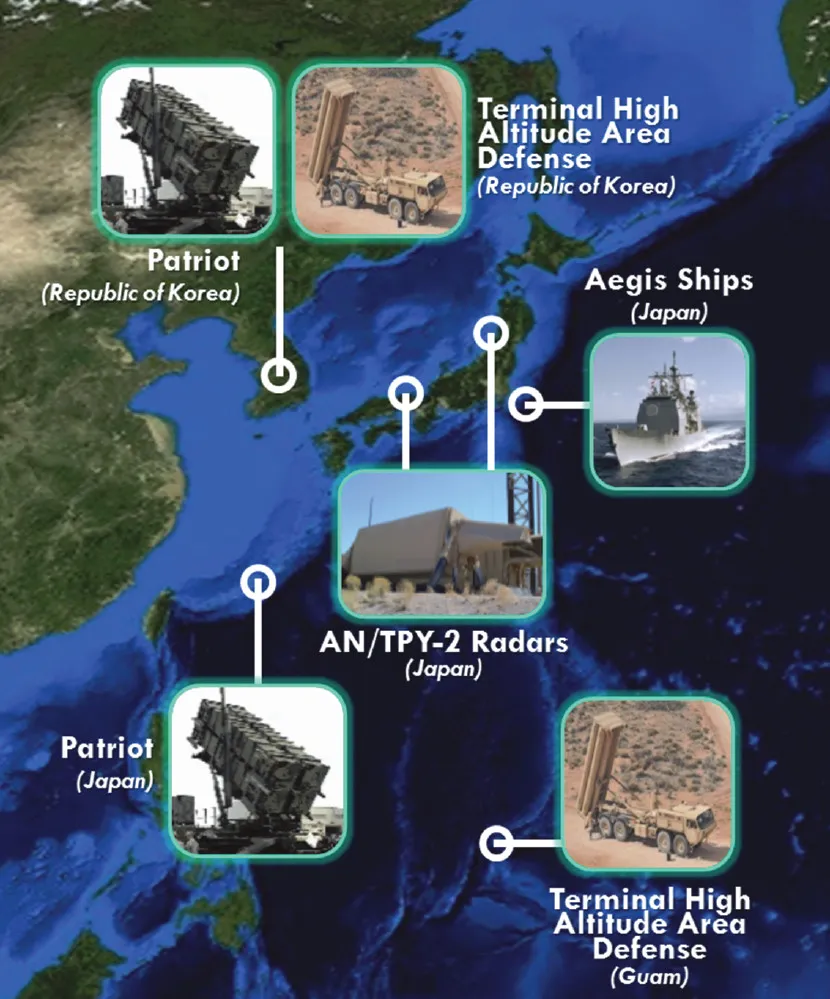

This would complement Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense-capable Arleigh Burke class guided-missile destroyers, or DDGs, in the region, as well as the lower-tier Terminal High Altitude Air Defense (THAAD) battery already on Guam. As The War Zone has highlighted on numerous occasions, the THAAD system is lower-tier missile defense asset more geared toward defending against very low-volume attacks, such as a limited ballistic missile strike from North Korea, rather than a major missile barrage from China. As such, Guam, an immensely strategic location in the Western Pacific for the United States, is vulnerable to larger scale missile strikes.

“The Guam defense system brings the same ability to protect Guam and the system itself as the three DDGs it would otherwise take to carry out the mission,” Davidson said during a virtual talk hosted by the American Enterprise Institute on March 4. “We need to free up those guided-missile destroyers, who have multi-mission capability to detect threats and finish threats under the sea, on the sea and above the sea, so that they can move with a mobile and maneuverable naval forces that they were designed to protect and provide their ballistic missile defense.”

“It doesn’t provide for a 360-degree defense necessarily,” he continued, talking about the THAAD systems on Guam. “It’s really designed to defend against a rogue shot from North Korea.”

The space-based radars would “provide low latency target custody and ground and air moving target indicators and represents a persistent queuing source” for both the Aegis Ashore system on Guam and the new radar in Palau. The constellation would also be able to “maintain situational awareness of adversary activities.” This is all well in line with other efforts within the U.S. military to significantly expand space-based sensor, as well as communications and data-sharing capabilities in the coming years.

This array of space and terrestrial sensors directly linked together would also align well with various distributed sensor and general battle management concepts being developed across the services, such as the U.S. Air Force’s Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS), the Army’s Integrated Battle Command System (IBCS), and the U.S. Navy’s Project Overmatch, as well as joint service programs, such as the Joint All Domain Command and Control (JADC2) effort.

Details are also scant on the “specialized” and “discreet” intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance aircraft that are part of the PDI spending plan. This does sound very similar to what the Army has been exploring through its Airborne Reconnaissance and Targeting Multi-Mission Intelligence System (ARTEMIS) program, including the Pacific.

ARTEMIS “provides high-altitude sensing capabilities against near-peer adversaries and bridges gaps in the Multi-Domain Operations mission,” the Army’s Program Executive Office for Aviation wrote in a post on Facebook in August 2020. “The joint investment between the Army and industry partners started in May 2019 and recently completed aircraft and sensor system engineering, airworthiness qualification, information assurance accreditation, integration and testing requirements and deployed to U.S. Indo-Pacific Command.”

The initial ARTEMIS platforms are a pair of modified contractor-owned and operated Bombardier Challenger 650 business jets. The exact configuration of these aircraft is not known, but they do carry the High-Accuracy Detection and Exploitation System (HADES) sensor suite, which includes a radar, as well as electronic intelligence (ELINT) and communications intelligence (COMINT) packages, to “allow [for] stand-off operations to detect, locate, identify and track critical targets for the ground commander,” according to a previous contracting notice.

It’s also worth noting that there have been indications that other elements of the U.S. government, including the Central Intelligence Agency, have been employing contractor-owned and operated aircraft in recent years to conduct overwater surveillance missions in the Pacific to monitor for North Korean sanctions violations. Those kinds of operations would also align well with this manned aerial surveillance component of the PDI proposal. They could be particularly well suited to monitoring for and documenting malign Chinese behavior, including harassment of foreign maritime commercial activities, something the U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard said would be an important day-to-day responsibility for their forces in the region in a tri-service strategy document released last year.

There are few granular details on exactly how the PDI would help expand “Power Projection, Dispersal, and Training Facilities” across the Pacific. At the same time, the U.S. military has already been pursuing various efforts to expand infrastructure on U.S. soil and in friendly countries in the Pacific that could support future distributed operations. In September 2020, American officials notably announced the completion of a Joint Improvement Project for Angaur Airfield in Palau, which included expanding the airstrip’s runway so that it can handle larger military and commercial aircraft. Angaur is now considered a useful alternative to Roman Tmetuchl International Airport on Babeldaob, the largest island in the archipelago nation.

“The U.S. and our allies must develop locations that provide expeditionary airfields for dispersal and ports for distributed fleet operations,” the executive summary of the PDI plan said, according to Breaking Defense. “Ground forces armed with long-range weapons in the First Island Chain allow USINDOPACOM to create temporary windows of localized air and maritime superiority, enabling maneuver. Additionally, amphibious forces create and exploit temporal and geographic uncertainty to impose costs and conduct forcible entry operations.”

“We are developing an integrated architecture to horizontally expand data sharing among like-minded nations through the use of information fusion centers in South Asia and South East Asia, as well as in Oceania,” INDOPACOM head Admiral Davidson had said in a speech on March 1. “These fusion centers will combine and analyze sensor data from aircraft ships and maritime picture between the US, our allies and our partners to improve our collective surveillance of potential illegal fishing trafficking activities and transnational threats.”

Of course, it remains to be seen how much of the PDI, as it is proposed now, will come to fruition in the coming years.

“It’s been fascinating to me, the relative ease at which the conversation happens year to year when it comes to the EDI [European Defense Initiative] when compared to PDI,” INDOPACOM head Davidson had said yesterday in defense of the Pacific defense spending plan. “Some of the angst has been mechanical right? The original European initiative had access to the [overseas contingency operations funding]. And that made it an easier lift.”

That being said, there is a growing, bipartisan consensus within the U.S. government that China represents the biggest national security challenge to the United States on multiple fronts. In a recent policy memo, U.S. Marine Corps Commandant General David Berger highlighted this reality by placed China in its own threat category, placing Russia in a lower-tier along with North Korea and Iran. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin has also made clear that China is the “pacing threat” for U.S. defense planning.

With support building for various efforts to respond to challenges from China, it seems very likely that at least some portions of this plan to expand ground-based long-range strike, missile defense, and sensor capabilities in the Pacific, as well as the infrastructure and networking needed to support those and other future operations in the region, will start to become a reality in the near term.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com