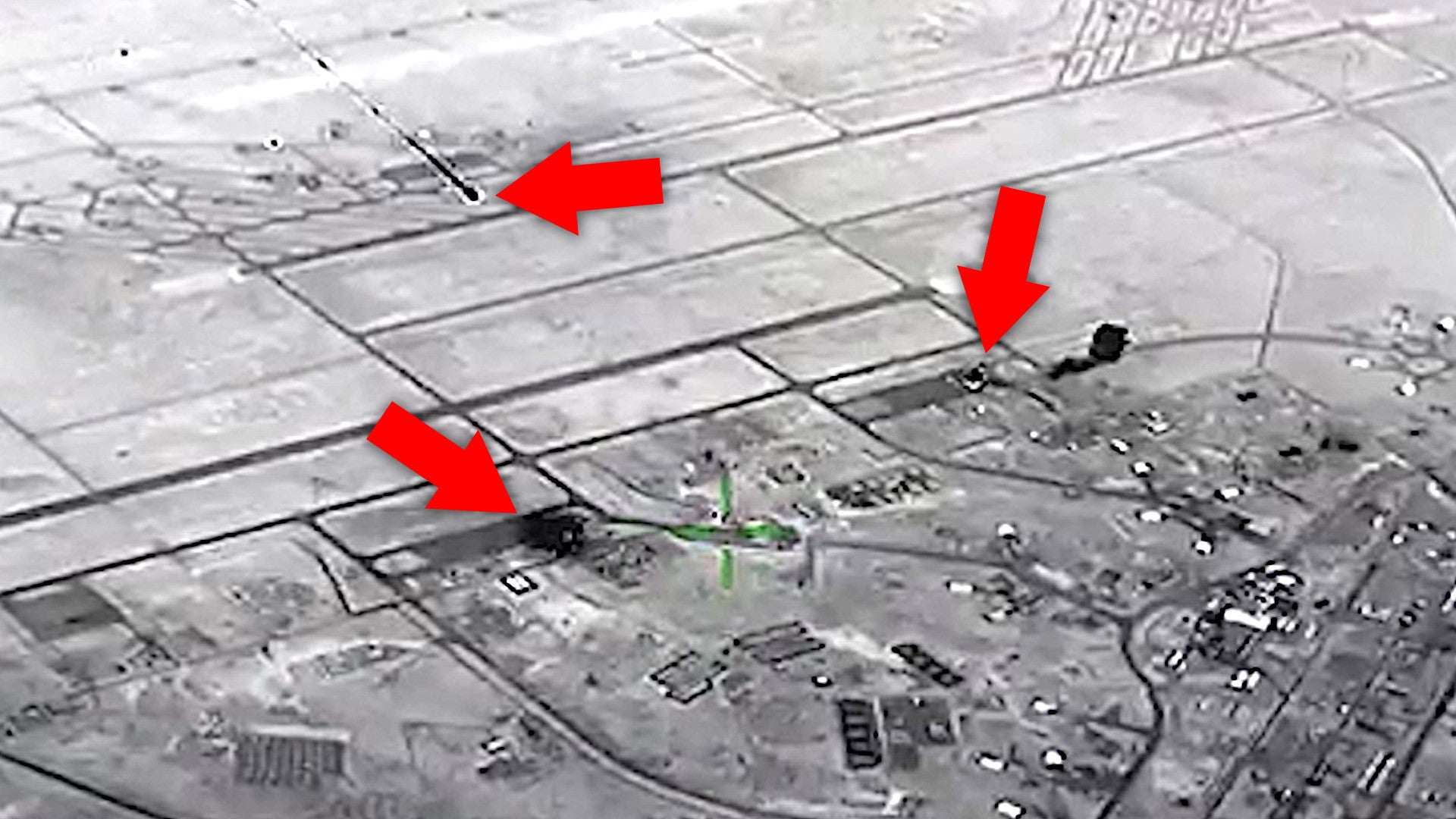

The U.S. military has released never-before-seen aerial surveillance footage of Al Asad Air Base in Iraq during the unprecedented Iranian ballistic missile strikes on that facility last year. The annotated video, shot by a drone orbiting overhead at the time, shows six Qiam-1 short-range ballistic missiles hitting the base.

U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), which is the top command overseeing American military activity in the Middle East, declassified the video and provided it first to CBS News‘ “60 Minutes” for a segment that aired this past weekend. The missile strikes themselves occurred on Jan. 8, 2020. Afterward, then-U.S. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper said that 11 Qiam-1s had hit Al Asad, in total. Officials in Iraq’s northern semi-autonomous Kurdish region also said that at least two short-range ballistic missiles had been fired at Erbil International Airport, which also hosts U.S. forces, one of which failed to reach its target.

U.S. Army Major Alan Johnson, who was at the base during the incident, told “60 Minutes” that intelligence had indicated Iran was preparing to fire as many as 27 missiles at Al Asad. The CBS News’ program also reported that a total of 16 missiles were ultimately launched at the base, with five failing to function as intended. Approximately 110 U.S. service members were later diagnosed with traumatic brain injuries, but thankfully there were no fatalities.

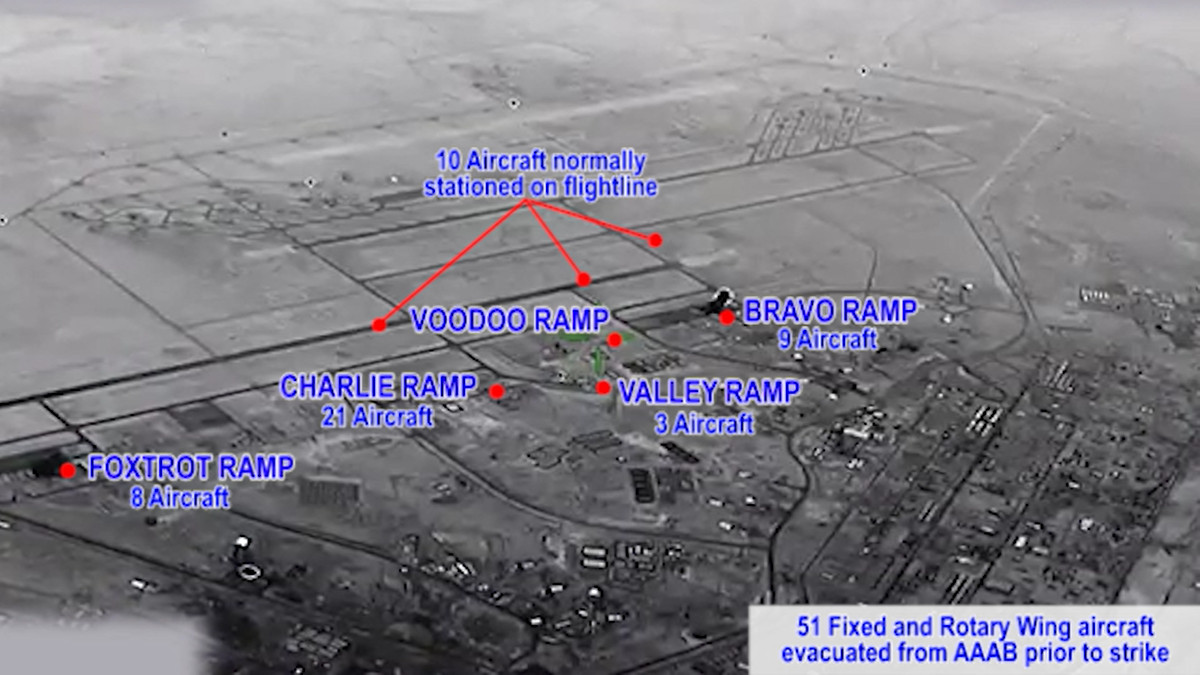

The footage, which you can watch in full below, starts by identifying five ramps at Al Asad – named Bravo, Charlie, Foxtrot, Valley, and Voodoo – and how many aircraft were positioned at the time of the attack. The on-screen notes also there are usually 10 aircraft on the flightline and that 51 fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters had evacuated the base ahead of the strikes. It was disclosed last year that U.S. early-warning satellites, later identified as the Space-Based Infrared System (SBIRS) constellation, provided critical advance notice, giving time for personnel to evacuate and for others to seek shelter.

“60 Minutes” has now revealed that the U.S. government also had additional indications well before the missiles began raining down that strikes were coming from monitoring Iranian purchases of commercial satellite imagery of Al Asad. U.S. Marine Corps General Frank McKenzie, head of CENTCOM, said he waited until intelligence told him the Iranians had downloaded their last commercial image of the base for the day before beginning evacuations and the movement of equipment. In doing so, they severely disrupted the effectiveness of the Iranian attack and likely saved many lives and lots of equipment in the process.

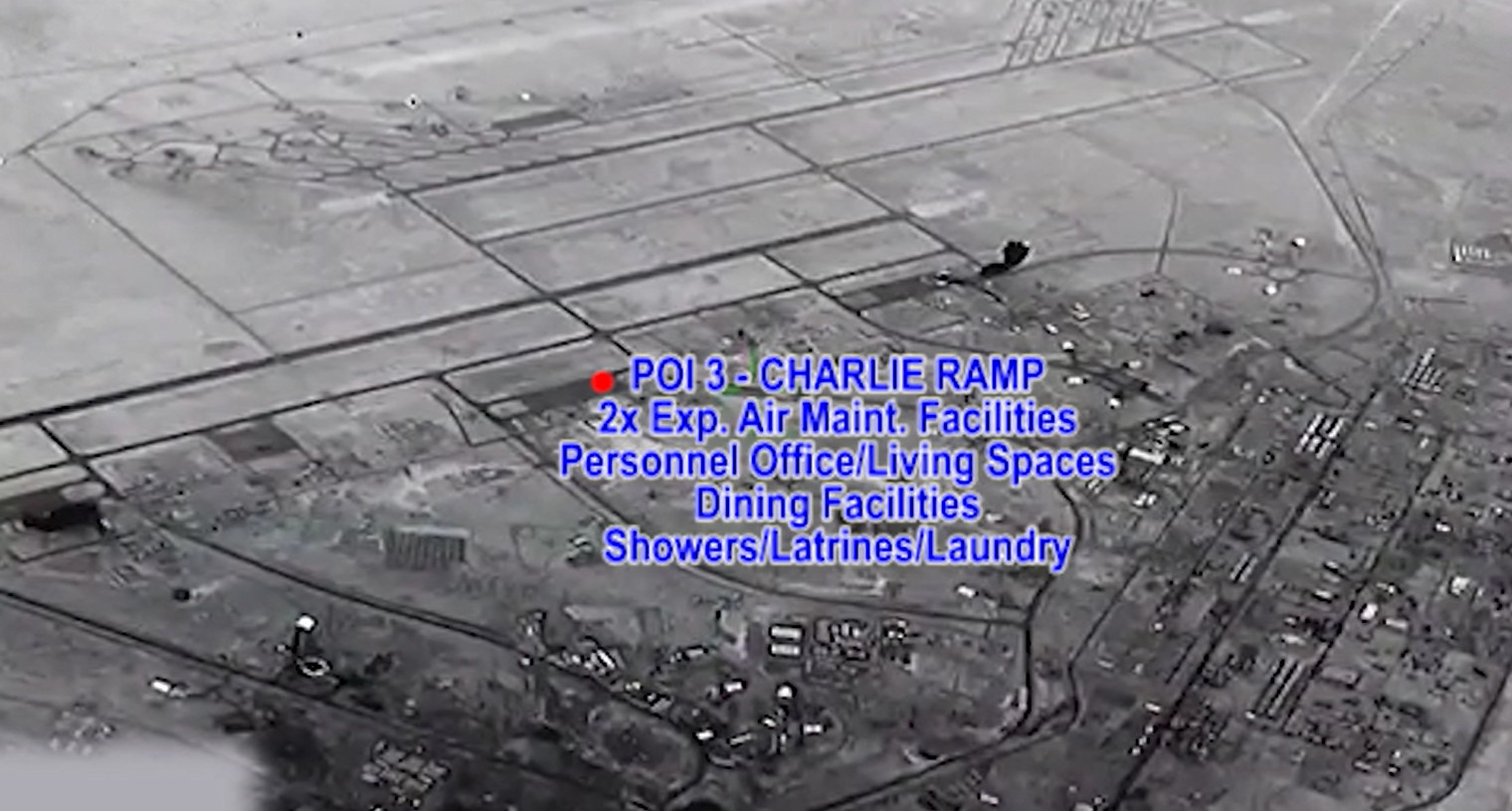

The video then moves on to show two missiles hitting “expeditionary air maintenance facilities,” a formal term for “tension-membrane” clamshell-type hangars, on the Bravo ramp. A third missile slams into the Charlie ramp, damaging additional clamshell hangars, as well as offices, living spaces, dining facilities, and latrines.

The fourth missile strikes the Voodoo ramp, hitting more clamshell hangars, as well as a fuel bladder. The last two missiles seen in the footage strike the Charlie and Valley ramps, hitting a rescue operations center, as well as maintenance facilities, a gym, and a dining hall.

It’s not clear what type of drone filmed the video in question, but it is known that a number of U.S. Army MQ-1C Gray Eagles were airborne at the time and that some were kept on station due to fears that a complex ground attack could follow the missile barrage. However, the strikes damaged fiber optic lines connecting ground control stations at Al Asad to satellite terminals, cutting them off from the unmanned aircraft overhead. This may also explain, in part, why only six of the 11 Qiam-1 impacts are seen in the footage.

The full “60 Minutes” segment, seen below, also shows previously unseen video of troops on the ground, who had moved away from Al Asad into the relative safety of the surrounding desert when the strikes began, watching additional missiles careen into the base.

Despite the early warning and the subsequent evacuations, there was still a need for at least some U.S. personnel to remain at the base. However, there were insufficient bunkers to shelter them all and many of those that were available were only designed to protect against smaller indirect threats, such as rockets, with warheads in the 60-pound-class or smaller, according to “60 Minutes.” The warheads in the Qiam-1s were in the 1,000-pound-class.

“[It] knocked the wind out of me, followed by the most putrid tasting ammonia tasting dust that swept through the bunker. Coated your teeth,” Army Major Johnson, one of 28 service members who later received Purple Hearts for injuries sustained in the strikes, told “60 Minutes” about one of the missiles hitting near the bunker where he and others were initially sheltering. “The fire was just rolling over the bunkers, like 70 feet in the air.”

“We’re going to burn to death. We start heading down 135 meters, make it about a third of the way there [to another bunker],” he continued. “The Big Voice, we call it, clicks in ‘INCOMING INCOMING TAKE COVER TAKE COVER TAKE COVER.’ I’ve got another football field to run. I don’t know when this next missile’s going to hit.”

“Big Voice,” also called “Giant Voice,” refers to one of a number of loudspeaker public address and alert systems that are installed at U.S. military bases, as well as other U.S. government facilities, at home and abroad. You can read more about these systems in this past War Zone piece.

Johnson and his companions did eventually make it to another bunker. However, they found some 40 other individuals there also trying to cram in. These shelters were designed to shield around 10 people at a time.

The Army officer described the feeling of the missiles crashing down around him “like a freight train going by you” and said that, in his opinion, “nobody should’ve lived through this.” His comments align closely with those from U.S. Air Force personnel at Al Asad during the strikes. That service released a compendium of personal stories from survivors of the strikes last year.

“I was being forced to gamble with my members’ lives by something I couldn’t control,” Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Staci Coleman, the commander of the 443rd Air Expeditionary Squadron at Al Asad, said. “I was deciding who would live and who would die.”

“The explosions finally stop, and I feel a collective sigh within the bunker,” Air Force Captain Nate Brown, in charge of the 443rd’s Engineer Flight, said afterward. “The next wave hits. Then the next, and the next. I have no idea if anyone is alive outside this bunker.”

“No one quite understood the magnitude of what we might be facing,” Air Force Captain Adella Ramos, head of 443rd’s Airfield Operations Flight, also said. “But as the night carried on, there was an unspoken understanding that this might be it. We might not live through this.”

The U.S. Army subsequently deployed air defense assets to Iraq, including Patriot surface-to-air missile batteries, to help protect against further missile strikes. There were no such air and missile defenses at the base at the time, which became something of a scandal.

More than a year later, tensions between the United States and Iran, as well as Iranian proxies throughout the Middle East, including Iraq, remain high. The “60 Minutes” segment notably aired less than a week after President Joe Biden ordered airstrikes on Iranian-backed Iraqi militias operating in neighboring Syria in response to a rocket attack on Erbil Airport earlier this year. That attack killed a contractor work for the U.S.-led coalition fighting ISIS in Iraq and Syria, as well as wounded a U.S. service member and four more contractors, among other casualties.

The Biden Administration has made clear that it is looking for rapprochement with Iran, including rejoining the controversial deal over Tehran’s nuclear program. At the same time, there are concerns that continued aggression from Iran, or its regional proxies, could lead to an escalatory spiral that could potentially result in something similar to the 2020 Al Asad strikes. It’s worth noting that that incident was the culmination of a series of events that had started with a fatal rocket attack in Iraq in December 2019, which subsequently prompted U.S. airstrikes on Iranian-backed militias in that country and in Syria.

That, in turn, led to a mob attack by Iran-backed groups on the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad, which was then followed by the U.S. government’s decision to kill Iranian General Qassem Soleimani outside Baghdad International Airport just days later. The Iranian missile strikes on Al Asad and Erbil were in direct retaliation for the death of Soleimani, who had been the head of the Quds Force, the part of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) responsible for external operations, including supporting and otherwise coordinating with proxies.

Had Iran’s ballistic missiles killed any Americans, let alone a large number of them, it’s not hard to see how that could easily have sparked a larger conflict. “Had Americans been killed, it would’ve been very different,” CENTCOM boss McKenzie told “60 Minutes.”

He added that it’s reasonable to believe that 20 to 30 aircraft might have been lost and 100 to 150 U.S. personnel might have died if not for the intelligence and other early-warning alerts ahead of the strikes. “We had a plan to retaliate if Americans had died,” McKeznie said bluntly.

The video footage that we now have, combined with the various first-hand accounts, only underscores just how real that danger was at the time and remains now.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com