For years, there has been very limited information available publicly about U.S. counter-terrorism operations in Somalia and the forces, based there and in neighboring countries, carrying them out. The repositioning of the bulk of American military forces out of this East African nation between December 2020 and January 2021, dubbed Operation Octave Quartz, highlighted those activities in a way that had not been previously seen. This has included the release of a significant number of what would have been previously been very rare pictures and video clips of U.S. personnel operating in and around the country. One picture that was recently released, seen at the top of this story, prominently shows what can be considered a “ghost aircraft.”

The twin-engine Beechcraft King Air turboprop aircraft with the U.S. civil registration number N27557 was photographed at Baledogle Military Airfield, which is situated some 55 miles northwest of the capital Mogadishu. It was included in a group of images related to the deployment of elements of the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU) to the base, sometime between the last week of December 2020 and the first week of January 2021, to provide security and other support as American troops pulled out. The Pentagon announced on Jan. 17, 2021, that the repositioning of the majority of U.S. forces out of Somalia was complete.

Baledogle, originally built by the Soviets during the Cold War, has been expanded and transformed over the past decade or so into a major hub for the U.S. military, as well as other foreign actors, such as the United Nations, and elements of Somalia’s own armed forces. It was notably the target of a complex attack by terrorists belonging to Al Shabaab, Al Qaeda’s franchise in the country, between Sept. 30 and Oct. 1, 2019. Since the mid-2000s, Al Shabaab has the primary focus of U.S. operations in Somalia, though the country now also has a nascent ISIS-aligned group.

A story from Foreign Policy in 2015 described the facility as a launch point for American unmanned aircraft and training site for Somali special operation forces. However, as is clear from the picture of N27557, as well as satellite imagery, manned fixed-wing aircraft, as well as helicopters, have also long operated from Baledogle.

From what is generally known, fixed-wing aircraft flying from Baledogle have primarily been configured for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) missions, supplementing unmanned aircraft in this role. While we don’t know N27557’s exact configuration, it has many features that are commonly seen on King Airs equipped for ISR operations.

One of the most immediately visible features is the large dome on top of the central fuselage, which is typically associated with high-bandwidth satellite communications and data-sharing systems. There are also three platter-type antennas – one in front and one behind the dome, as well one on top of the aircraft’s t-tail – which are also generally connected to ultra-high-frequency satellite communications equipment. There are additional angled blade antennas that typically are linked to ultra or very-high-frequency radios on top of and below the fuselage.

As for visible sensors, the aircraft’s configuration is much more spartan. Compared to other ISR-configured King Airs, N27557 lacks an underbelly equipment gondola and does not have a sensor turret carrying various kinds of full-motion video cameras under the rear fuselage. It’s hard to tell for sure, but there does not appear to be anything of major significance mounted externally under the forward fuselage, either, judging the by shadow.

The aircraft does have a number of straight blade antennas underneath the fuselage of a type sometimes associated with systems to intercept enemy communications chatter, including from cell phones, or other kinds of signals intelligence.

More interestingly, it has an odd, angled system underneath the rear fuselage where a sensor turret would commonly be found. While we don’t know for sure what this is, one possibility is that conceals some kind of camera system. ISR-configured aircraft often have cameras installed behind sliding doors that are designed to interfere with the airflow around the aircraft as little as possible when they are opened. There are two visible segments on the “face” of the system underneath N27557, which could be a sliding door arrangement of some kind.

As for what kind of camera or cameras might then be installed here, one possibility is a wide-area airborne surveillance (WAAS) system designed to collect imagery across a very large area all at once. WAAS systems are used for conducting persistent surveillance to help establish so-called “patterns of life” that can help in the tracking and targeting of small groups or even specific individuals. Combined with signals intelligence, it can help create a very high-fidelity intelligence “picture” of how terrorists and militants are operating in a specific area. You can read more about how this works in this past War Zone piece.

Historically, WAAS systems have been relatively large, but more compact designs are increasingly available and still offer impressive capabilities. Logos Technologies’ RedKite and BlackKite wide-area motion imagery (WAMI) sensors are prime examples and are designed to be installed at a fixed, oblique angle, just like the system underneath N27557’s fuselage. They are also sized to fit even inside relatively small drones, such as the Boeing Insitu RQ-21 Blackjack. The U.S. Marine Corps is in the process of acquiring an improved version of BlackKite, known as Cardcounter, for its Blackjacks.

There is also the possibility that this is a mounting point for dispensers for countermeasures, such as decoy flares. However, if this is where flare launchers might be installed, it’s hard to see why they would they wouldn’t be fitted when flying over Somalia. Al Shabaab is known to possess shoulder-fired, heat-seeking surface-to-air missiles, also known as Man-Portable Air Defense Systems (MANPADS).

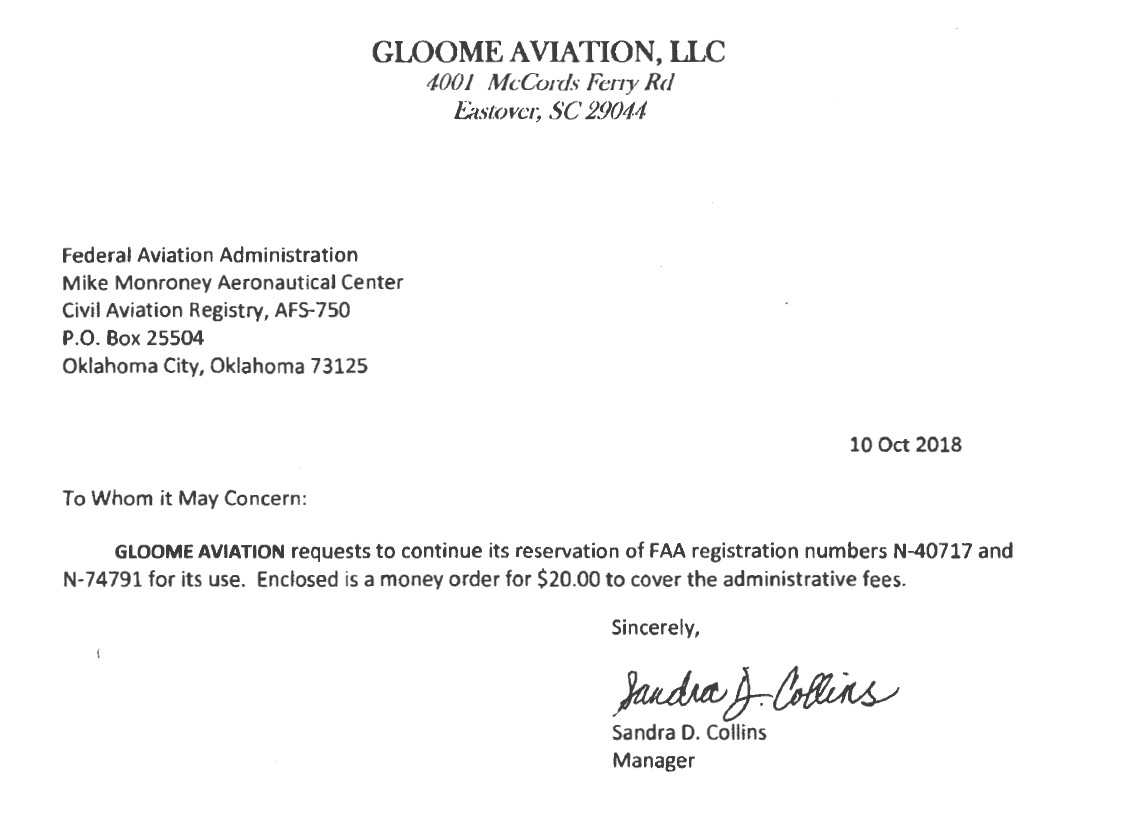

If the aircraft’s configuration is curious, so is the question of who is operating it. See, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) says that there is no plane of any kind associated with the registration number N27557. A company called Gloome Aviation paid a $10 fee to reserve this number for a year, starting on June 18, 2020, according to FAA’s database, but no subsequent paperwork to link it to a specific aircraft appears to have been filed.

The FAA database also says that Gloome provided the following physical address when it reserved this N-number: 4001 McCords Ferry Road, Eastover, South Carolina, 29044-8854. This is the exact address, down to the extended ZIP code, of International Paper’s facility in Eastover, South Carolina.

When contacted in 2019 regarding a separate matter dealing with Gloome Aviation, Tom Ryan, Director of Corporate Communications at International Paper, told The War Zone “we have zero idea what this is about” and that “there is no relationship here whatsoever” between the two companies. At that time, Gloome had two other N-numbers reserved, N40717 and N74791. At present, it only has N27557 on hold.

Between 2017 and 2019, N40717 appeared on online flight tracking software multiple times flying what appeared to be ISR missions over Iraq, often using the callsign Rampant 11. Starting around the same time and as recently as January of this year, N74791 has also showed up on flight tracking websites over Iraq, sometimes with the callsign Rampant 12, flying the same sorts of orbits. N40717 and N74791 have also been associated with the callsigns State 34 and State 36, respectively.

Interestingly, since 2019, the callsign State 33 has been associated with the flights of four shadowy Lockheed L-100 aircraft, commercial derivatives of the C-130 airlifter, over Iraq, as well as Syria and Jordan. These aircraft, which have the U.S. civil registration numbers N2679C, N2731G, N3796B, and N3867X, are all linked to a company called Tepper Aviation, based out of Bob Sikes Airport in Crestview, Florida. Tepper has long been associated with the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

It wouldn’t be surprising that the CIA, or contractors working on its behalf, would be conducting its own aerial ISR operations using discreet aircraft like N27557. The Agency is understood to have a very robust presence in the country, working actively together with its Somali counterpart, the National Intelligence and Security Agency (NISA).

The CIA has reportedly been involved in the training of NISA’s own direct-action counter-terrorism forces, called Gaashaan, or “shield,” and Waran, as well as their operations. In November 2020, reports had emerged that a member of the Agency’s own paramilitary arm, known as the Special Activities Center, had been wounded and later died in a raid on Al Shabaab terrorists.

The fact that other aircraft linked to Gloome Aviation have been seen in the Middle East using military-type callsigns could also indicate that the activities of these planes, including N27557, might also be linked to top-secret U.S. military aviation elements, which are themselves often associated with the secretive Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC). There has long been considerable evidence of overlap in the control of aviation assets supporting JSOC and CIA activities, especially when it comes to unmanned aircraft.

There are also substantial reported ties between the Agency and military aviation elements that provide more specialized capabilities, such as the Army’s Aviation Technology Office (ATO), previously known as the Flight Concepts Division (FCD), as well as JSOC’s Aviation Tactics Evaluation Group (AVTEG). ATO/FCD, which itself evolved out of a joint Army-CIA aviation unit called Seaspray, is notably understood to have led the development of the heavily modified “Stealth Hawk” helicopters that were employed in the raid that led to the death of then-Al Qaeda leader Osama Bin Laden in Pakistan 2011. In addition to this kind of advanced development work, it also provides other kinds of specialized and discreet aviation support using a fleet of non-standard aircraft, including foreign types, such as Russian-made Mi-17 Hip helicopters.

JSOC is also known to make use of a publicly acknowledged fleet of civil-registered aircraft with civilian-style paint schemes, including multiple King Airs and larger de Havilland Dash-8 twin-engine turboprops, which are configured for ISR missions, including for missions over Somalia. You can read more about the Special Operations Command (SOCOM) Tactical Airborne Multi-Sensor Platform program, or STAMP, which The War Zone

was first to report on, here. One of the STAMP Dash-8s was among the aircraft destroyed in a brazen attack by Al Shabaab terrorists on an air base in Kenya that U.S. forces operate from in January 2020.

Regardless of who is operating N27557, with the recent drawdown of U.S. military forces from Somalia proper, at least of the elements that the Pentagon had acknowledged were in the country, there could now be increased emphasis on using the CIA and other covert or clandestine forces to continue executing more direct operations against Al Shabaab, as well as ISIS. The Pentagon has said that cross-border raids, staged from neighboring countries, such as Djibouti or Kenya, will continue to be an option for direct action against these terrorists, as well.

All told, whether they are supporting CIA or military activities, or both, shadowy aircraft like N27557 are likely to remain a fixture over Somalia as U.S. counter-terrorism operations in Somalia enter this new phase.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com