More than four decades after the Soviet Union’s 23mm R-23M automatic cannon became the first and only gun to have actually been fired in space, at least that we know about, a new picture of this secretive weapon has emerged. The image offers the clearest look to date of the entire Shchit-1 self-defense system that armed the Almaz OPS-2 military space station, which orbited the Earth for around eight months between 1974 and 1975.

Russian author Anatoly Zak, who also runs the website RussianSpaceWeb.com, spotted the Shchit-1 system in images the Russian Ministry of Defense released of Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu’s visit to NPO Mashinostroyenia earlier in 2021. NPO Mashinostroyenia, originally known simply as OKB-52, is a design bureau best known for the development of missiles, rockets, and spacecraft, including work on the Almaz military space program during the Cold War.

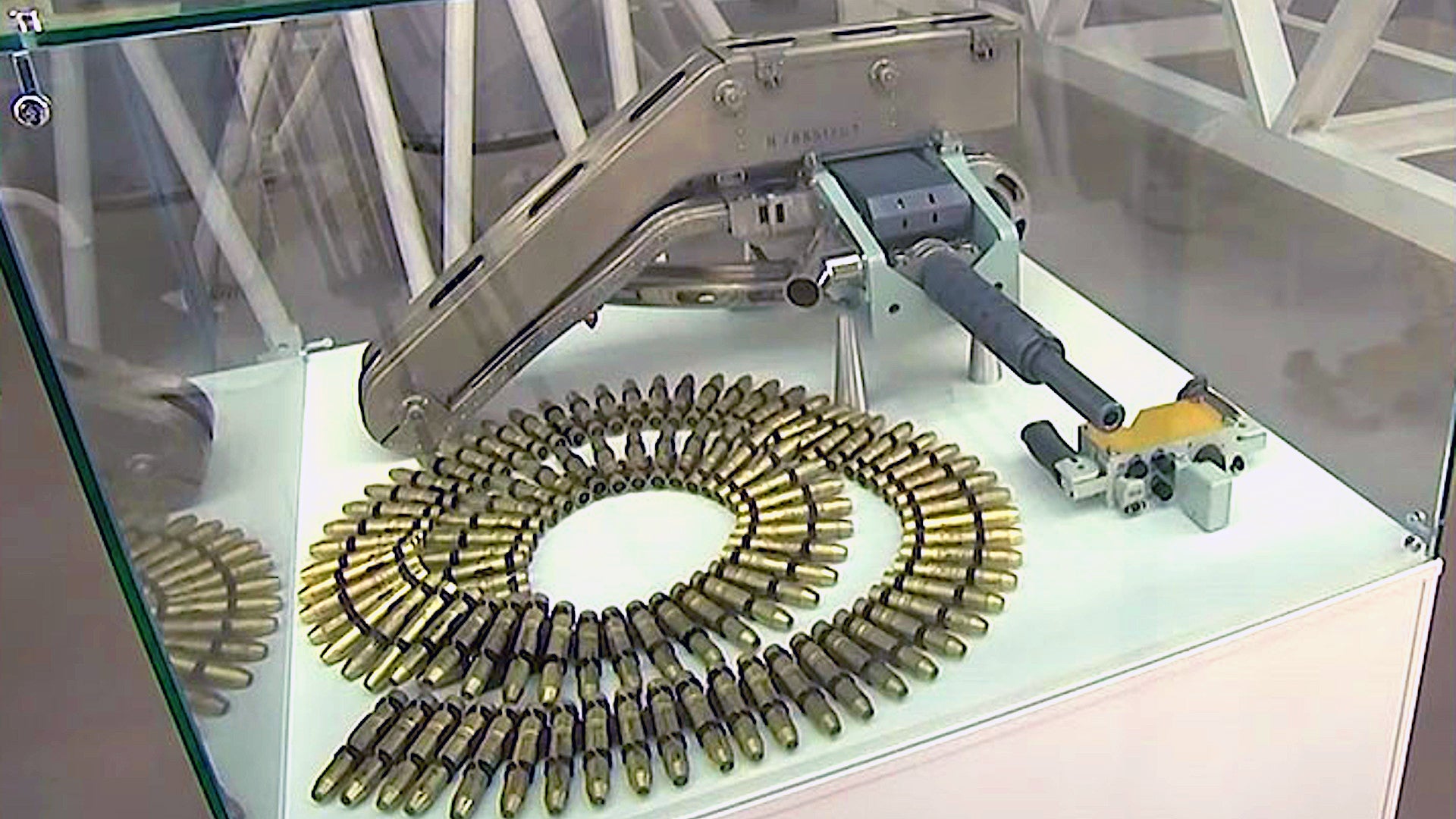

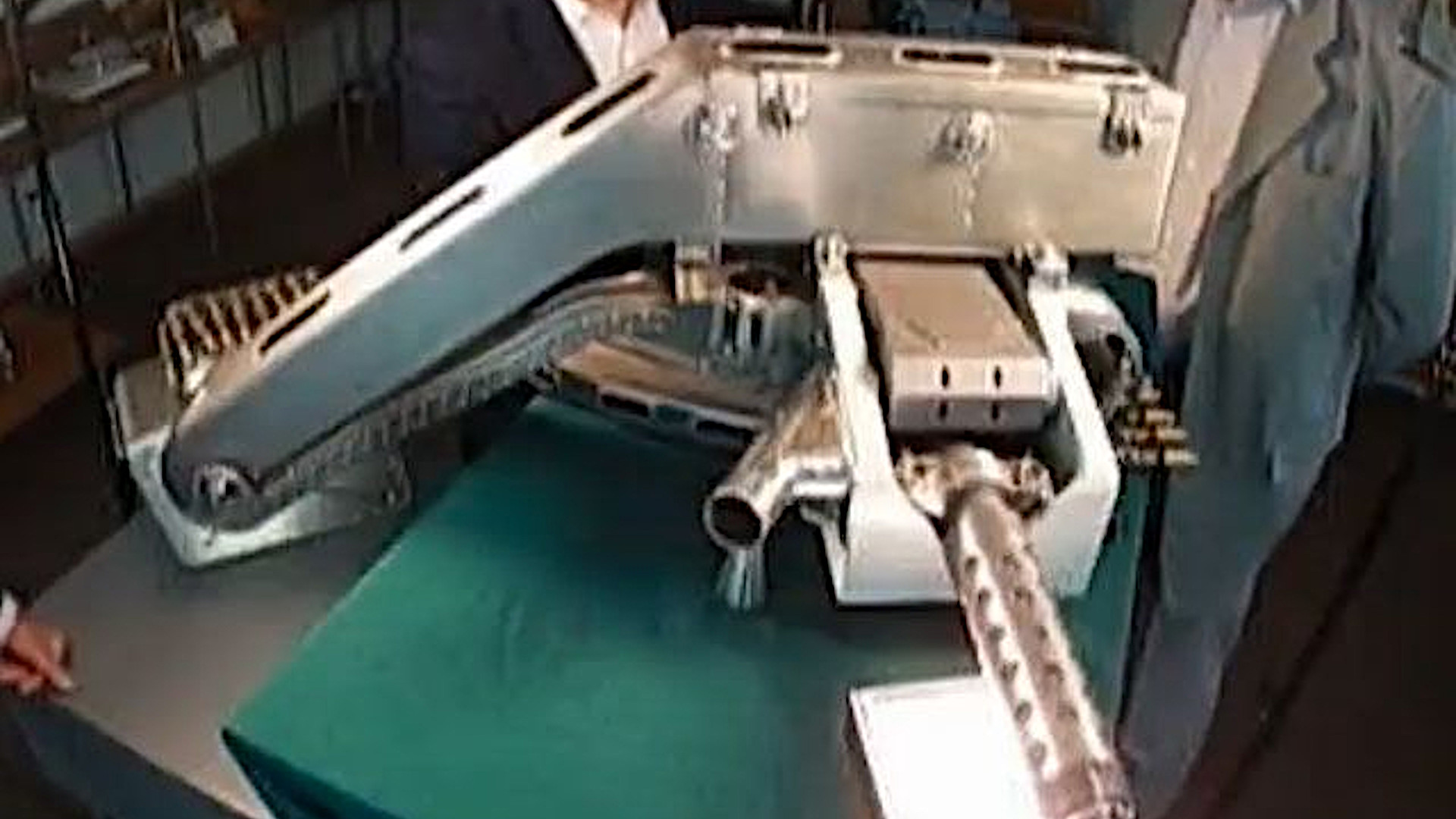

For years, the R-23M and the Almaz program were both wrapped in multiple layers of secrecy for various reasons. The fact that the OPS-2 space station was armed at all did not emerge until after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. There was only one available picture of the R-23M prior to 2015, and not a very good one, which may have only reflected a prototype design and did not show the complete Shchit-1 system. In 2015, a special aired on TV Zvezda, the official television channel of the Russian Ministry of Defense, which included the first real look, seen above, of the entire space-based configuration.

Development of the standard terrestrial R-23, designed primarily as self-defense weapons for bombers, began in the 1950s and was treated as a highly sensitive project. The brainchild of Aron Rikhter at KB Tochmash, a design bureau then headed up by Aleksandr Nudelman, the idea had been to craft a more compact gun that would be easier to fit inside an aircraft and particularly well-suited for turreted applications. Rikhter had worked directly with Nudelman on the earlier, unrelated 23mm NR-23, as well as the larger 30mm NR-30, both of which saw widespread use on Soviet aircraft.

The R-23 is a so-called revolver cannon, which, as its name indicates, feeds ammunition into the firing position by way of a number of revolver-like cylinders. This feed mechanism, which is similar in some very broad respects to Gatling-type designs, allows for a higher rate of fire than can be achieved with more conventional single-barrel guns.

However, Rikhter’s gun, unlike most other revolver cannons, feeds ammunition from the magazine backward into the cylinders, rather than from the rear or the side. This places the feed mechanism in the center of the gun, helping to shorten its overall length.

On top of that, the R-23 uses unique 23x260mm cartridges that have a so-called telescoped configuration. This means that the projectile is nestled completely inside the cartridge case, rather than sticking out of the front. The general concept behind ammunition of this type is to shorten the overall length of the round, and, by extension, the weapon that fires it, without any significant loss of performance over a gun firing a similar traditional round.

The Tupolev Tu-22 Blinder bomber was the first aircraft to be designed to carry the R-23, with one of the guns to be mounted in a remote-controlled, radar-directed turret in the tail. Delays in the development of the cannon meant that the first Blinders entered service years before their tail guns were ready.

In the end, the Tu-22 was the only aircraft to be armed with the R-23. This helped keep the very existence of the gun largely secret until the first Blinders were exported to Iraq and Libya in the 1970s. An actual example did not reportedly fall into Western hands until one was recovered from the wreckage of a Libyan Tu-22 that French forces had shot down over Chad in 1987. That conflict between Chad and Libya, in general, was an intelligence bonanza for the West.

It’s not clear whether or not the development of the R-23M for space-based applications contributed to the secrecy surrounding the weapon or if it was chosen because it was so closely guarded to start with. Its compact nature no doubt helped make it an obvious choice for attaching to a spacecraft, where weight and physical space are always at a premium.

Based on the still limited information that has emerged to date, the Shchit-1 self-defense system consisted of a single R-23M cannon in a rigid mount with a magazine mounted on top of the center portion of the gun. What modifications may have been made to the weapon itself to ensure it would function properly in zero gravity are unclear.

“From the dawn of the Space Age, the secrecy-obsessed Soviet military was terrified by the prospect of American spacecraft approaching and inspecting Soviet military satellites—which, according to the Kremlin’s propaganda, were not even supposed to exist,” Anatoly Zak wrote in a piece on the R-23M for Popular Mechanics in 2015. “This wasn’t crazy. The fear of attack on spacecraft was real, with both sides of the Iron Curtain developing anti-satellite weapons. It seemed perfectly logical in the 1960s that military and piloted spacecraft would need self-defense weapons.”

The Almaz military space stations, work on which first began in the early 1960s, were intended to be armed from the beginning. Before shifting to the R-23M, Zak says that KB Tochmash had been working on a compact 14.5mm weapon for space-based use.

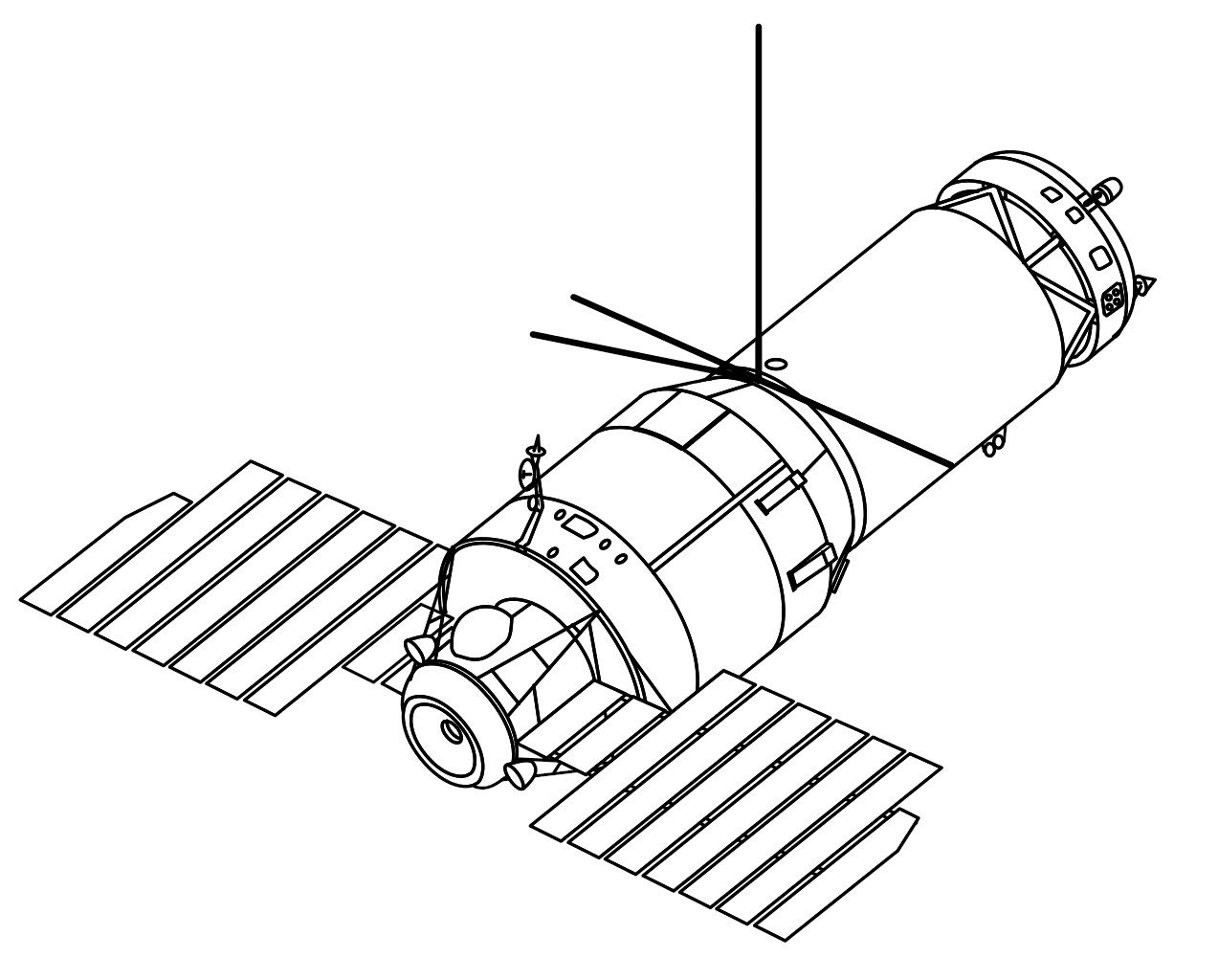

The Almaz stations were expected to be multi-purpose military platforms in space. The plan was for the first types to be configured primarily for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions with cameras and other sensors. Delays with the development of the sensor package held up the entire program. In 1971, the Soviet Union launched a civilian space station, Salyut, that incorporated some of the design work developed under the Almaz program, together with components from the venerable Soyuz spacecraft.

The Salyut program ultimately provided a cover for the Almaz space stations. Of the seven Salyut space stations launched between 1971 and 1991, three were actually military types.

The first Almaz station, referred to publicly as Salyut-2 and also known as OPS-1, was launched in 1973. However, an accident on board shortly after launch forced the Soviets to abandon it before an actual crew could be sent up to join it.

OPS-2, also called Salyut-3, followed in 1974. This station, armed with the R-23M, successfully reached orbit on June 25 of that year, but a two-man crew did not arrive until July. They remained there for 15 days, during which they tested the onboard telescopic Agat-1 Earth-observation camera, which is said to have been able to produce imagery of the ground with a resolution of better than three meters.

A second crew failed to reach the station later in 1974 after their Soyuz spacecraft suffered a malfunction. The third mission to OPS-2 was subsequently canceled and it operated in an unmanned mode until it deorbited on January 24, 1975. In September 1974, personnel on the ground remotely ejected a pod with film from the Agat-1 camera, which subsequently returned to Earth and was recovered.

The test of the R-23M cannon occurred on the station’s very last day in orbit. Without any way to fully simulate on the ground how firing the gun would impact OPS-2, the plan had always been to test it in orbit without anyone on board. The shock and recoil not only had the potential to damage the station but, in the vacuum of space, those forces raised the possibility that shooting the weapon could send it flying in a dangerously unpredictable fashion.

“The outpost [OPS-2] ignited its jet thrusters simultaneously with firing the cannon to counteract the weapon’s powerful recoil,” Anatoly Zak explained in the story for Popular Mechanics back in 2015. “According to various sources, the cannon fired from one to three blasts [bursts], reportedly firing around 20 shells in all. They burned up in the atmosphere, too.”

Exactly what happened during the test remains classified to this day. The next Almaz space station, known as OPS-3 and Salyut-5, had no weaponry on board, at least that we know of. Plans for an OPS-4 station included a new Shchit-2 self-defense system that was reportedly designed to fire missile-like interceptors, but no pictures of that weapon are known to exist publicly.

The Soviets did also develop specialized self-defense guns for cosmonauts, such as the TP-82 seen in the video below, but these were intended to be used on Earth, not in space. You can read more about them in this past War Zone piece.

How effective the Shchit-1 system would ever have been had it seen more widespread use is certainly debatable. The fixed mounting meant that the entire space station had to be rotated to aim it, which would reportedly have been done using a simple optical sight.

In the years since the test of the R-23M in space, the prospect of attacks on satellites and other spacecraft certainly hasn’t gone away, nor has an interest in weapons that could be used in orbit for defensive or offensive purposes. Last year, the head of U.S. Space Force, the U.S. military’s newest branch, publicly accused Russia of having tested an on-orbit projectile-based anti-satellite weapon. It’s interesting to note that what little we know about the Shchit-2 system would seem to fit this general description.

At the same time, Russia has also been testing relatively small inspector satellites, which have the ability to get very close to other objects in space. This could allow them to function as orbital spies, as well as “killer satellites,” using various means of attack to damage, disable, or destroy a target, including by simply smashing into it.

These kinds of threats have prompted discussion in other countries, including the United States and France, about the development of potential countermeasures, if they don’t exist already in the classified realm. The French military, specifically, says it is now working on space-based “guardian satellites” that will be armed with lasers, though it’s unclear if they will be powerful enough to physically damage or destroy an incoming threat or will just be designed as dazzlers to blind or confuse enemy sensor and seeker systems.

The story of the R-23M certainly highlights just how complex and sensitive the matter of developing even the most basic weapons for space-based applications remains, a full 46 years after the Soviets conducted the one known test of an automatic cannon in orbit.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com