Details are still limited, but the Chinese government says that it has carried out an anti-ballistic missile test. State media reports say that the goal was to demonstrate capabilities to intercept an intermediate-range ballistic missile, or IRBM, during the midcourse portion of its flight. However, these kinds of interceptors can also double as anti-satellite weapons.

China’s Ministry of Defense announced the test on Feb. 4, 2021, and said it achieved all of its goals, but offered no additional details, including whether an actual intercept of any kind had taken place. Chinese authorities also insisted that the test was purely defensive in nature and was not meant a signal to any country in particular.

Unconfirmed video of a possible rocket or missile launch emanating from northern China has emerged on social media. The clips are similar to imagery that appeared online after another anti-ballistic missile test in 2018, but are also what one would expect to see from any large rocket or missile launch. If this footage is from this test, it could indicate a launch from the Taiyuan Satellite Launch Center in Shanxi Province, which is also a major Chinese ballistic missile test facility.

This test may also help explain the presence of a U.S. Air Force RC-135S Cobra Ball that was observed flying in the Yellow Sea earlier this week via online flight tracking data. There are only three of these aircraft in total, which are specially configured to gather telemetry and other electronic intelligence, from missile and other large rocket launches, making them very-low-density, but high demand assets.

The appearance of one of these aircraft, which you can read about in more detail in this past War Zone piece, in any particular area can often be a sign of an imminent missile test. Flying in this particular area of the Yellow Sea would have put the RC-135S as close as possible to Taiyuan while remaining in international waters.

The 2018 test was also described as being a demonstration of midcourse ballistic missile intercept capabilities. So far, China has not yet released any specific details about work on such an interceptor, including any official designation. The country is “developing kinetic-kill vehicle technology to field a midcourse interceptor, which will form the upper layer of a multi-tiered missile defense,” according to the most recent annual public report from the Pentagon on Chinese military capabilities, which it released last September.

A “kinetic-kill” interceptor, also known as a hit-to-kill type, is designed to destroy its target by physically slamming into it, rather than via a traditional warhead or some other kind of effect. The U.S. military’s own Ground-based Midcourse Defense (GMD) interceptors, a test of which is seen in the video below, use a kinetic kill vehicle. Difficulties in the development of that vehicle have become a major issue for the GMD program in recent years.

The interceptor itself only one part of the puzzle of midcourse ballistic missile defense, which you can read more about broadly in this previous War Zone piece. This involves detecting, tracking, and then engaging longer-range ballistic missiles, including IRBMs and intercontinental ballistic missiles (IBCM), after they “go cold” from entering the vacuum of space, as well as discriminating between them and any decoys. This presents significant challenges and requires a robust, multi-layered sensor network that would include assets in space, in addition to ones on the Earth’s surface.

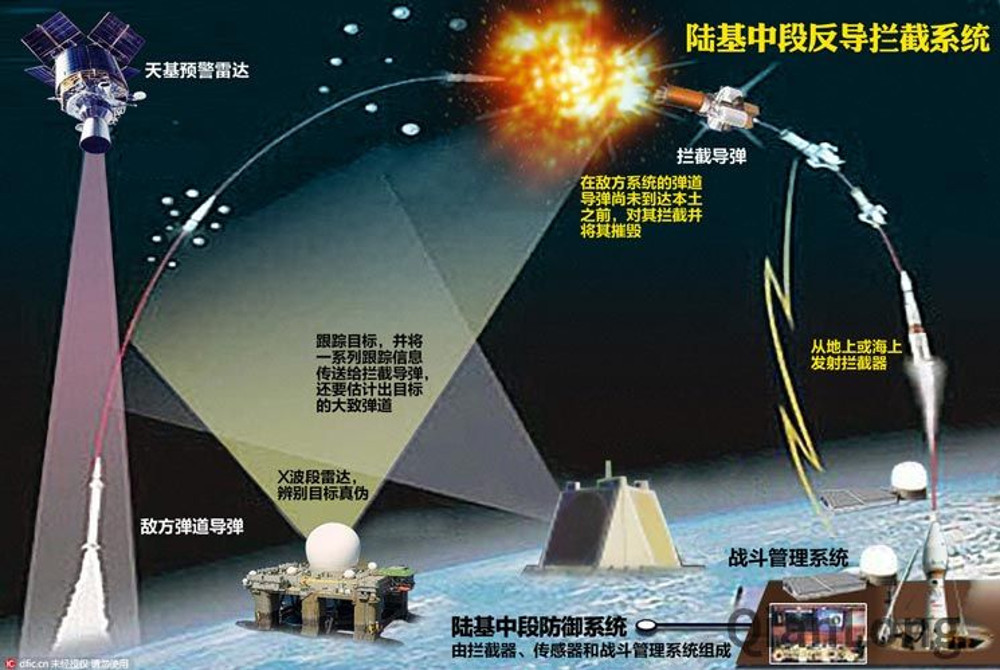

Interesting, after the 2018 test, a story in the People’s Daily newspaper in China, an official media outlet of the Chinese Communist Party, including the graphic below outlining the principles of midcourse ballistic missile defense using components of the U.S. military’s system, including the GMD interceptor, Sea-based X-band Radar (SBX), a portion of the land-based Solid State Phased Array Radar System (SSPARS), and a Defense Support Program (DSP) satellite. In recent years, the U.S. military has continued to work toward adding additional sensor nodes, especially in space, to its overarching missile defense ecosystem.

In addition, it’s important to point out that the line between midcourse ballistic missile interceptors and anti-satellite weapons is extremely thin. The U.S. government has gone so far as to accuse China of using such ballistic missile defense tests as cover for anti-satellite weapon testing in the past.

It may well be that China’s midcourse interceptor is an extension of work the country had done on the Dong Neng series of anti-satellite interceptors, which themselves use boosters from ballistic missiles, such as the DF-11. Reports have said that Dong Neng-3 (DN-3) was the interceptor employed in the 2018 test, reportedly knocking down target in the form of a DF-21 medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM).

China is also known to be working on a surface-to-air missile system, the HQ-19, which reportedly also has some degree of exoatmospheric intercept capability. Reports also indicate that the Dong Neng-2 (DN-2), as well as another interceptor, known as the SC-19, can also engage targets in space.

The HQ-19 is also known to the U.S. Intelligence Community as the CH-AB-X-02, with the X indicating that it is still assessed to be experimental and not fielded operation. However, that naming convention would suggest the existence of another anti-ballistic missile defense interceptor, the CH-AB-01 or CH-AB-X-01, which could refer to this midcourse interceptor.

Regardless, it’s not hard to see how China would be interested in both midcourse ballistic missile defenses and improved anti-satellite capabilities. The Chinese government faces potential threats from India’s ballistic missile arsenal, as well as potential new ballistic missile and ballistic missile-based hypersonic weapon developments in South Korea and Japan. There is also the matter of the United States, which is in the process of modernizing its strategic ballistic missile systems. The U.S. military is also now also exploring the possibility of acquiring new IRBMs, and potentially MRBMs, following the collapse of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, or INF, with Russia, with a specific eye toward deploying them on China’s doorstep in the Pacific.

Space is also an area where there are growing concerns of potential conflict. The U.S. military, in particular, has come to heavily rely on space-based systems for a wide variety of functions, including early warning, intelligence gathering, weapon guidance and basic navigation, and communications and data-sharing. All of this has only incentivized potential adversaries to develop ways to destroy or disable American satellites, or those of its allies and partners, to neutralize those capabilities. You can read more about all of this in these previous War Zone stories. It’s also worth pointing out that the U.S. government has been increasingly willing to publicly call out what it assesses to be anti-satellite tests in recent years.

All told, it will certainly be interesting to see what details emerge about this test and times goes, including from sources outside of China, especially the U.S. government.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com