Airspace security has become a more pressing defense issue over the last decade as unmanned aerial systems, or UAS, have continued to proliferate. The War Zone has reported extensively on these incursions, including some over our most sensitive infrastructure sites and critical defense installations. In an attempt to address this new security threat, then-President Donald Trump signed an Executive Order on January 18, 2021, titled “Executive Order on Protecting The United States From Certain Unmanned Aircraft Systems.”

The order restricts and excludes drone technologies from countries deemed adversarial, while also instructing the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to update its policies concerning airspace over sensitive infrastructure sites. The original text of the order is no longer visible on the White House’s website due to the recent Presidential transition, but an archived version can be viewed here.

The primary aim of the Executive Order is to “prevent the use of taxpayer dollars to procure UAS that present unacceptable risks and are manufactured by, or contain software or critical electronic components from, foreign adversaries, and to encourage the use of domestically produced UAS.” To that end, the order instructs all heads of executive branch departments and agencies to conduct thorough reviews of current UAS technologies and suppliers to ensure there are no threats from technologies built by adversary countries.

The order defines “adversary country” as “the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, the Islamic Republic of Iran, the People’s Republic of China, the Russian Federation, or, as determined by the Secretary of Commerce, any other foreign nation, foreign area, or foreign non-government entity engaging in long-term patterns or serious instances of conduct significantly adverse to the national or economic security of the United States.” The order bans the federal use of any UAS systems or technologies from any of those countries including: electronic components, flight controllers, ground control system processors, radios, digital transmission devices, cameras, sensors, or gimbals; operating systems and other UAS-related software including mobile applications, and even “network connectivity or data storage located outside the United States, or administered by any entity domiciled in an adversary country.”

Various agencies of the U.S. government have been highlighting the potential security risks of using Chinese-made drones for years now, with a heavy focus on concerns about what information the manufacturers collect through their products after they’re sold. In 2017, the U.S. Army went so far as to ban the use of any drones from Chinese firm DJI. Last year, the Trump Administration placed DJI, one of the world’s largest drone manufacturers, on the Commerce Department’s Entity List of blacklisted companies from which American companies are banned from exporting technology.

In January 2020, the Department of the Interior (DOI) had also grounded its UAS fleet in January 2020 until certain “cybersecurity, technology and domestic production concerns are adequately addressed.” Those concerns also stemmed from the fact that the DOI’s fleet of over 800 drones was manufactured in China or used parts manufactured in China. So-called “backdoor” exploits have become a chief cybersecurity and infrastructure threat, as it remains unknown to what extent the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) could leverage Chinese-made hardware to access or affect American networks and systems that depend upon it. Similar issues led the Trump Administration, as well as Congress, to push back against the use of Chinese technology in the establishment of 5G mobile phone and WiFi networks at home and abroad.

In addition, the January 18 Executive Order concerning UAS comes in the wake of other policy initiatives and high-profile incidents involving the threat of unfriendly unmanned aerial systems in our skies. More and more civilian and military aircraft are having near misses with drones, while sensitive sites like the Palo Verde Nuclear Power Plant or the critical THAAD Anti-Ballistic Missile Battery in Guam have had their own recent drone incursions.

In late 2019 and early 2020, news spread of reports of unidentified drone swarms in the skies over Colorado and Nebraska, not far from ICBM sites operated by F.E. Warren Air Force Base. The War Zone has been pursuing an investigation into these drone incidents, but so far it seems that even most of America’s civil aviation authorities remain as perplexed by the incursions as we are. Perhaps in response to these unexplained drone incursions and others like it, the Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) published a December 2020 report outlining steps that could be taken to mitigate the threat that small UAS pose to sensitive federal sites.

This new Executive Order takes the CISA recommendations even further by calling for a review of the existing federal UAS fleet. The reviews called for in the January 18, 2021, Executive Order are extensive. Heads of each agency and department are instructed to review every UAS procurement with which they are involved and determine if each could be ceased:

Sec. 2. Reviewing Federal Government Authority to Limit Government Procurement of Covered UAS. (a) The heads of all executive departments and agencies (agencies) shall review their respective authorities to determine whether, and to what extent consistent with applicable law, they could cease:

(i) directly procuring or indirectly procuring through a third party, such as a contractor, a covered UAS;

(ii) providing Federal financial assistance (e.g., through award of a grant) that may be used to procure a covered UAS;

(iii) entering into, or renewing, a contract, order, or other commitment for the procurement of a covered UAS; or

(iv) otherwise providing Federal funding for the procurement of a covered UAS.

(b) After conducting the review described in subsection (a) of this section, the heads of all agencies shall each submit a report to the Director of the Office of Management and Budget identifying any authority to take the actions outlined in subsections (a)(i) through (iv) of this section.

Continuing this, the next section of the order requires the Director of National Intelligence, the Secretary of Defense, the Attorney General, the Secretary of Homeland Security, the Director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy, and the heads of “other agencies, as appropriate” to submit a report to the President that assesses the risks posed by the current federal UAS fleet:

Sec. 3. Reviewing Federal Government Use of UAS. (a) Within 60 days of the date of this order, the heads of all agencies shall each submit a report to the Director of National Intelligence and the Director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy describing the manufacturer, model, and any relevant security protocols for all UAS currently owned or operated by their respective agency, or controlled by their agency through a third party, such as a contractor, that are manufactured by foreign adversaries or have significant components that are manufactured by foreign adversaries.

(b) Within 180 days of the date of this order, the Director of National Intelligence, in consultation with the Secretary of Defense, the Attorney General, the Secretary of Homeland Security, the Director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy, and the heads of other agencies, as appropriate, shall review the reports required by subsection (a) of this section and submit a report to the President assessing the security risks posed by the existing Federal UAS fleet and outlining potential steps that could be taken to mitigate these risks, including, if warranted, discontinuing all Federal use of covered UAS and the expeditious removal of UAS from Federal service.

Heads of agencies are instructed to prioritize the costs of replacing any UAS deemed to be a threat into their budgets, and instructs the Director of the Office of Management and Budget to work with agency heads to “identify possible sources of funding to replace covered UAS in the Federal fleet in future submissions of the President’s Budget request.”

Section 4 of the order deals exclusively with securing airspace over sensitive sites and locations, and instructs the FAA to create new regulations in accordance with its existing UAS safety laws:

Sec. 4. Restricting Use of UAS On or Over Critical Infrastructure or Other Sensitive Sites. Within 270 days of the date of this order, the Administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) shall propose regulations pursuant to section 2209 of the FAA Extension, Safety, and Security Act of 2016 (Public Law 114-190).

Section 2209 of the FAA Extension, Safety, and Security Act of 2016 can be read in its entirety on the FAA’s website. The section defines certain sensitive sites including “critical infrastructure, such as energy production, transmission, and distribution facilities and equipment,” oil refineries and chemical facilities, amusement parks, and “other locations that warrant such restrictions,” and prohibits and restricts the operation of unmanned aerial systems in close proximity to those sites.

Our previous investigation showed that after unexplained drone incursions at the Palo Verde nuclear power plant in 2019, Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) staff discussed how to approach drone incursions, but there was some doubt as to how effective airspace restrictions could be at preventing future incursions. This occurred even after it came to light that dozens of similar incursions had happened over nuclear-related sites in recent years.

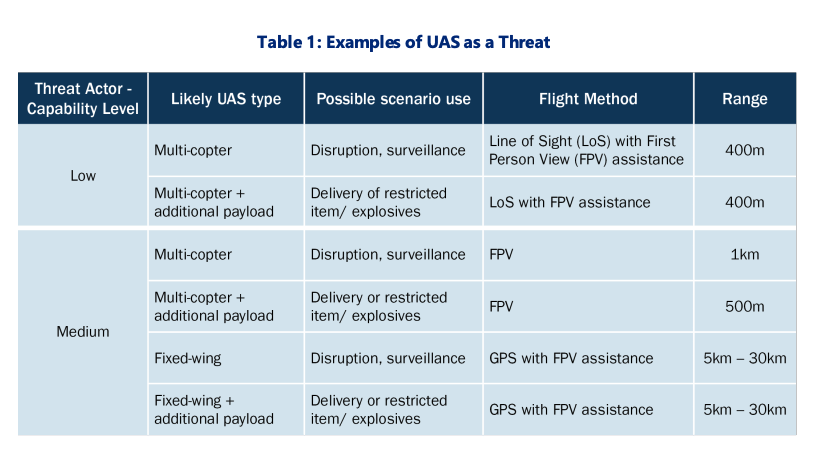

The War Zone has been reporting on the topic of the threats posed by small drones for years. Actors of all sizes, from peer-rival nation states to drug cartels are weaponizing small drones at an alarming rate, and our ability to defend against these attacks have not yet caught up to the rapid technological advancement these drones have seen in recent years.

Executive Orders like this one signed just days ago will force even reluctant government agencies to continue to evaluate what the risks posed by off-the-shelf drones are and what can be done to best mitigate them.

Contact the author: