On the early morning of January 12, 1981, 40 years ago today, 11 commandos from a Puerto Rican separatist organization broke through the perimeter fence at Muñiz Air National Guard Base on the island, armed with explosives. Their targets were aircraft from the Puerto Rico Air National Guard. What followed was not only the most destructive single attack on U.S. military forces since the Vietnam War up to that date, but also the most significant material loss from any single act of terrorism against the U.S. Air Force anywhere in the world.

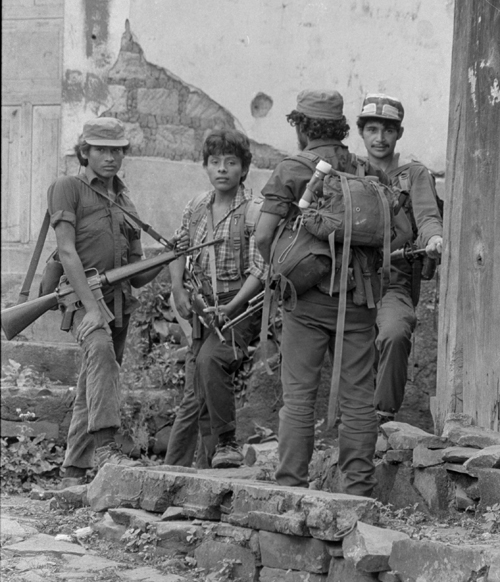

The commandos were from the Boricua Popular Army, or Ejército Popular Boricua, also known as the “Macheteros” — machete wielders in Spanish — a clandestine organization looking to secure Puerto Rico’s independence from the United States. Located in the Caribbean Sea, Puerto Rico has been an American unincorporated territory since the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898. While controlled by the U.S. Federal Government, it is essentially a colony. Its inhabitants are U.S. citizens, but can’t vote in presidential elections and have only one representative in Congress, who can’t vote on legislative matters.

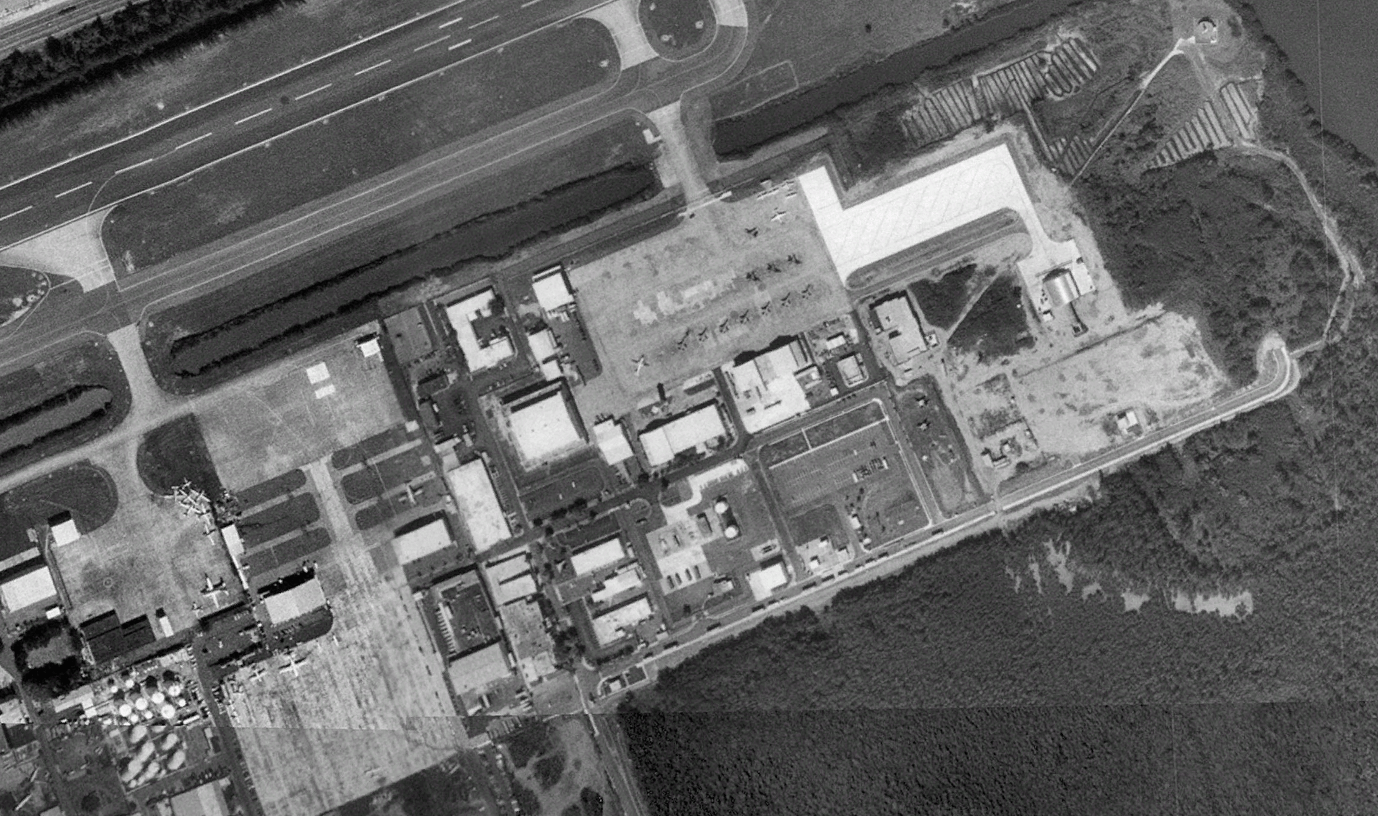

The island has a number of military facilities, including, as of 1981, Roosevelt Roads Naval Station and Muñiz Air National Guard Base, the latter of which is located on the outskirts of San Juan, Puerto Rico’s capital and co-located with the island’s international airport.

The Boricua Popular Army’s attack on Muñiz Air National Guard Base was timed to coincide with the birthdate of Eugenio María de Hostos, a 19th-century Puerto Rican independence advocate. Using military uniforms to disguise themselves, the commandos breached the airbase perimeter fence — which was not electrified — by simply cutting through a chain-link fence. It’s unclear how they got to the ramp for the Air National Guard’s A-7 Corsair II attack aircraft, but contemporary reports suggest at least some of the “Macheteros” may have used a boat to navigate one of the many channels running around the facility, connecting various lagoons with the island’s Atlantic coast.

Likely aided by insider information, or close surveillance, the infiltrators arrived on the airbase just as its security personnel was changing shifts. The various guards — both Air National Guard personnel and contracted civilians — were apparently unaware that trespassers were within the facility.

The separatists were carrying explosives that had been stolen from a local explosives factory, all part of an operation that was apparently codenamed Operation Pitirre II. The pitirre is a bird, also known as the gray kingbird, which is native to Puerto Rico, among other islands in the Caribbean.

Around 25 satchel charges were placed on 11 aircraft on the ramp, in their air intake ducts, or wheel wells. Each pack contained four sticks of Iremite, an explosive normally used for blasting in commercial mining. To ensure a 60-minute time delay, a simple but effective watch-and-battery setup was used to trigger the detonators.

Then, the commandos left the same way that they had entered the airbase. The whole process had apparently taken less than eight minutes.

The resulting explosions at Muñiz Air National Guard Base damaged 10 A-7D aircraft out of a total of 18 at the base belonging to the 156th Tactical Fighter Group, as well as a single F-104C Starfighter. The latter type had previously been in service with the Puerto Rico Air National Guard and this particular example was earmarked to be preserved as a static display.

Eight of the A-7Ds were written off entirely, two more damaged, and the value of the total material loss was put at around $45 million. Bombs on two other A-7Ds did not detonate and were later dismantled by U.S. Navy explosives technicians.

Never before had an Air Force facility on U.S. soil come under terrorist attack, nor had terrorists previously destroyed Air Force aircraft in peacetime.

A day after the attack, the Boricua Popular Army claimed responsibility, issuing a statement denouncing the U.S. Air Force for “invading our homeland” and “[exposing] our people to nuclear extermination,” and also pointing to “revolutionary solidarity with the brotherly people of El Salvador and their revolutionary organizations.” The communique also named four individuals whose deaths the organization blamed on the U.S. regime, including two pro-independence activists. At this time, guerrillas in El Salvador were waging their own, far more violent conflict against the U.S.-backed military government of that country, which was, at the time, notorious for its use of paramilitary death squads.

The initial fallout from the incident focused on how easily the perpetrators had entered and then left the base and the degree of damage that they had inflicted in such a short space of time. Not since the Vietnam War had a U.S. airbase sustained such a devastating attack. During the fighting in Southeast Asia, these types of raids had invariably been carried out by North Vietnamese forces, or at least highly trained and battle-hardened local Communist guerrillas, using purpose-made weapons.

While the National Guard Bureau had apparently been aware of the insufficient security at the base, it had yet to take action when the separatists struck. Immediately after, the level of protection at the base was enhanced, the number of guards on patrol at any one time was increased from 10 to 60, and an electrified perimeter fence was added. Other security recommendations included making improvements to lighting around the base, adding an alarm system, increasing training of security personnel, and installing a closed-circuit television system.

At the same time, the Air Force Chief of Staff requested that the commanders of all the service’s Major Commands review their own security programs and look at areas where possible improvements could be made. As a result of this study, funds were made available for security enhancements at 44 airbases considered to be under a high level of threat, 15 of which were overseas.

Furthermore, as part of the Five Year Defense Plan beginning in Fiscal Year 1984, other improvements were made, including the provision of four-man fire teams, additional lighting at selected bases, and more vehicles, radios, and personal equipment sets for security units. The budget for the following fiscal year added antiterrorism components to a range of existing training programs, including basic military training.

A criminal investigation into the attack was launched by the FBI, but does not seem to have yielded any prosecutions.

In the meantime, years of asymmetric conflicts in the Middle East and elsewhere have brought security of U.S. airbases — and other military installations — more sharply into focus, while the range of threats to these facilities has increased. In Afghanistan, in particular, U.S. airbases faced a serious threat from Taliban insurgents, with the most notorious attack occurring at Camp Bastion in Helmand Province in March 2012. In that incident, the Taliban made it onto the base and caused chaos, killing two, wounding many more, and destroying or badly damaging nine aircraft.

As for Puerto Rico, the number of military bases on the island was reduced sharply following the end of the Cold War. The Puerto Rico Air National Guard stopped flying combat jets in 1998, trading its F-16 Vipers for C-130 Hercules transport aircraft, and transforming into the 156th Airlift Wing. It lost its flying mission entirely in 2019, less than two years after Hurricane Maria battered its main base and nearly a year after a tragic accident exposed a culture of apathy and poor morale. It has since reorganized its former flying units to support the U.S. Air Force’s recent push to revitalize its ability to rapidly deploy and establish forward bases overseas during major crises and conflicts.

The Boricua Popular Army still exists, but multiple arrests of its members in the 1980s, followed by a restructuring of the organization and then the killing of its leader, Filiberto Ojeda Ríos, in a botched arrest operation by the FBI in 2005, all had a significant effect.

Since then, multiple non-binding referendums have been held on the future status of Puerto Rico. Most recently, in November 2020, a majority of residents voted in favor of becoming a U.S. state.

This all, however, remains a contested issue within the U.S. government at the national level, as well as among Puerto Rico’s own leading political parties, and the long-term position of the territory in regards to the United States is yet to be resolved.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com