From overcoming his fears and personal roadblocks in order to master the complex art of submarine hunting to heading out on his first carrier cruise and working to fit into the Navy’s unique squadron culture to chasing-down Soviet submarines in the Mediterranean during the twilight of the Cold War, Kevin Noonan has strapped us into an S-3 Viking right beside him and has taken us on a thrilling ride. Now, in this fourth and final installment in our Confessions Of An Ancient Sub Hunter series, Noonan reflects on what was and what could have been for the enigmatic S-3, as well as the challenges looming on the horizon for the U.S. Navy’s shrunken anti-submarine warfare community and for the service overall.

We talk everything from secretive ES-3A Shadows, short-lived US-3A ‘Miss Piggies,’ how the Viking and her crews fought to make a name for themselves within the carrier air wing, the relevancy of the aircraft carrier in modern warfare, and what it is really like being the ‘guy in the back’ of a combat jet. So, strap back in, spool-up the turbofans, and prepare to launch!

The Viking’s Place In The Carrier Air Wing Pecking Order

‘Harpooning’ the Viking will meet another criticism of the aircraft made by traditional carrier aviators, who feel that the embarkation of fixed-wing ASW aircraft has compromised the concept of the attack carrier, and reduced its striking power. – An Illustrated Guide to Modern Naval Aviation and Aircraft Carriers

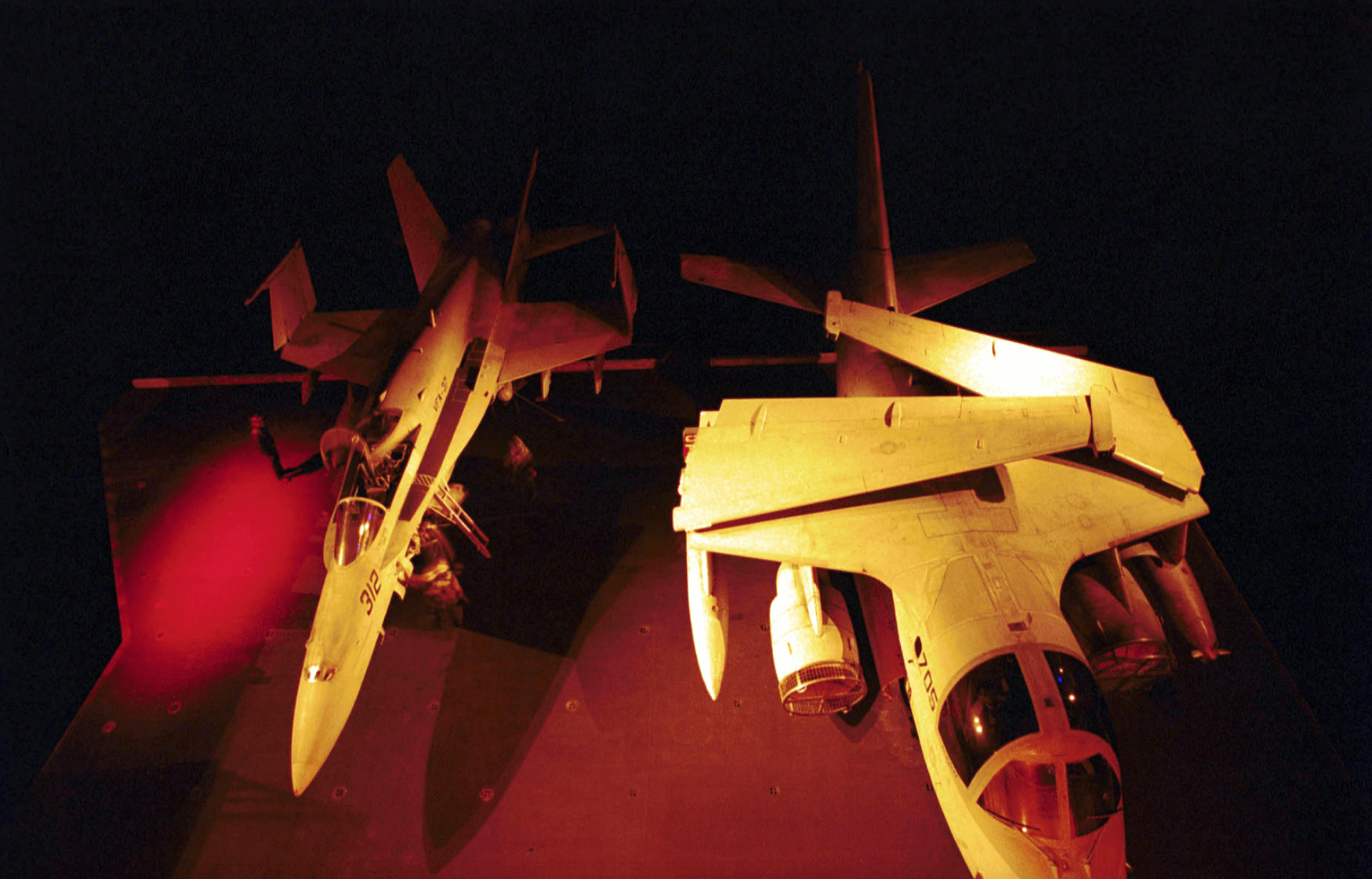

With the decommissioning of the Essex class anti-submarine warfare (ASW) carriers and the introduction of the S-3 to the supercarriers, deck space that was already at a premium was now jealously coveted. Fighter and attack guys, as well as carrier skippers and air wing commanders (CAGs), wanted as many F-4s, F-14s, A-4s, A-6s, and A-7s as possible to carry out the mission of the attack carrier. The presence of a handful of E-2s, EA-6Bs, and helicopters was tolerated since they served their masters well. The Viking, however, really did nothing to enhance their concept of the warfare they were charged with conducting. So, can you imagine what these gentlemen were thinking in the early to mid-1970s when a squadron of ten S-3 Vikings suddenly invaded their sacred deck-space?

Just to give you an idea of how much space, here are the S-3’s sexy measurements: Her wingspan was 68 feet with the wings spread or 29 feet with them folded. Her length was 53 feet. She stood tall at almost 23 feet, or 15 feet with her tail folded. By the way, at the apex of wings’ spreading or folding, the height of the Viking was 31 feet!

Among the punishments doled out for our excessive presence on the sovereign four and a half acres of fighter-attack territory, administered to all VS squadrons upon entering the Med [the Mediterranean Sea], was the banishment of two or three of our birds to the purgatory of Naval Air Station Sigonella, Sicily. What they assumed was punishment was actually a two to three-week vacation from the boat.

We would change-out aircraft and crews and maintenance personnel in order to give everyone a chance to ‘suffer.’ Ya know? I never did thank CAG and the fighter-attack guys for this! If there was a submarine in the general vicinity of Sicily, we would go out for a hunt. Otherwise, tasking while at ‘Sig’ tended to focus on recon of the Soviet anchorage just off of Tunisia or tracking the various ships the Soviets sent into the Med that steamed past Sicily.

Unfortunately, far worse for our reputation than the obesity of our presence on the carrier was that perennial problem plaguing the “A” model of the S-3, the one I touched on above.

Give me a moment to shed a little more light on the subject:

Since the technology placed in the Viking by Univac and Texas Instruments was cutting-edge for a carrier-based aircraft, our computer took a long time getting used to the standard-issue violence any aircraft endured during a catapult launch or arrested landing. Industry, engineers and NAVAIR evaluators at Pax River [Naval Air Station Patuxent River in Maryland] worked hard to eliminate the software and hardware problems that came to light as flight hours mounted through the 1970s. However, they never were able to completely cure a painfully regular problem associated with our Tape Transport Cartridge (TTC).

Basically, the TTC was a “floppy” disk that booted up the aircraft computer and had relevant software that could be loaded by the ASMOD [Anti-Submarine Modules, an intelligence element that coordinates ASW operations] for the pending mission (ESM [electronic support measures] emitters, target data, Link 11 info, fly-to-points, etc.). If we had any problems with the load while on deck, we’d shut down the #2 engine and one of our amazing AXs or ATs would come in and troubleshoot. The AX rating was an electronics technician that focused on our ASW black boxes. The ATs were electronics technicians that focused on aircraft electronics other than ASW gear. As the Cold War came to an end, the AX rating was retired and absorbed into the AT rating.

Keep in mind, we normally flew with a regular Air Wing cycle, which meant we launched with the E-2 ahead of perhaps four Tomcats, five A-6s, and four A-7s. If our troubleshooting took too long, the fighters and attack birds would launch ahead of us. When a problem didn’t get resolved, we were now affecting deck spotting for the previous cycle that had been waiting in the overhead stack to recover. Once we did launch, then everyone kept their fingers crossed that the computer’s load would hold.

Many times it didn’t.

The utter shock the aircraft suffers at the end of the cat stroke makes every airplane tremble. Can you imagine, then, how it is for any sensitive electronics on board? This is what occurred with each launch for the GPDC [general purpose digital computer] in the S-3A. As late as 1987, we were required to inform the Air Boss or Alpha X-ray of the status of our load once we were airborne: Alpha – fully working system. Bravo or Charlie – computer working in degraded state with only some sensors working. Delta – no computer load. When we reluctantly reported a Delta load, you could hear the wailing and gnashing of teeth in the voice of the Air Boss or Alpha X-ray.

Essentially, we were just a hunk of aluminum boring holes in CAG’s sky. If he was having a really bad day, he’d tell the Air Boss to send us to “Delta overhead and await the next recovery,” which meant we had to fly a purgatorial pattern above the ship and burn precious Air Wing fuel until we could land again. Our lack of a system meant no ESM, no radar except in an analog mode that couldn’t provide the battle group with any Link 11 surface plot data since the computer wasn’t working, no acoustics, nothing.

It took a long time for the S-3 to earn the respect she deserved. I’ve since discovered that there was a move in NAVAIR during the late ‘70s to early ‘80s to remove the S-3 from the carrier deck altogether and modify the airframes to be permanent tankers, CODs [Carrier Onboard Delivery], and a design to replace the Whale [the A-3 Skywarrior], all things that would actually come to pass. Thankfully, the complete removal didn’t happen. Someone somewhere was fighting for us—at least they were back then.

As the prominence of Vietnam-era dogfights and airstrikes faded with the close of the ‘70s and the increasing Soviet threat to the carrier battleground (CVBG) invaded the minds of senior officers, attitudes toward the Viking did begin to change. Then, as the decade of the ‘80s came to a close, significant changes were made to the S-3. Each of these changes, such as an exciting new radar, supplying the fighter-attack guys with the sweet nectar of JP-5 jet fuel from our own loins, and the Harpooning of the Viking, would contribute to the removal of the chip on the shoulder of the Air Wing and carrier toward the S-3, for the most part, anyway. Aboard some carriers, the Viking community would actually experience genuine respectful admiration, and dare I say…love?

Most importantly, damning computer loading problems would vanish.

Vikings Onboard

It took time for the ship’s company and air wing crews to get used to the presence of the S-3 Viking squadrons. We adapted, and by the time I walked aboard the USS Nimitz at the end of 1986 and headed off for my first Med cruise, the Viking community was just another squadron in the sea of 5000-6000 sailors aboard. They certainly didn’t love us — nonetheless, we were family.

Onboard Nimitz, we were well established with our ready room, our maintenance spaces, and our berthing. Most importantly, to the AWs (Aviation Warfare Systems Operators) of VS-24, we had our own aircrew shop where we held shop meetings, did our various collateral duties, got our asses chewed out by the Chief, “smoked and Coked,” and played computer games on the shop’s Commodore 64…Yes, you read that right.

As aircrew, we didn’t suffer the 12 hours on, 12 hours off schedule that our squadron mates and ship’s company had to endure every day we were at sea. We lived according to our flight schedule.

During a Med cruise, an AW Shop tended to have between 14 and 17 Naval aircrewman. With 10 aircraft, we could man the birds, day and night, and still have three SENSOs [sensor operators] to stand Assistant Squadron Duty Officer watch in the ready room. When we weren’t briefing and flying, we were sleeping, training, and studying Soviet naval vessel recognition and tactics or doing our collateral duties such as filling out all the squadron aircrew log books, calculating crew/aircraft flight time and mission statistics, updating classified publications and NATOPS manuals.

My berthing aboard the Nimitz was particularly amazing. It was a 20 man-berth that was curtained off. It was our own sanctuary that was essentially off-limits to everyone. We could sleep day or night without interruption. I was grateful that I had a top rack (what the Navy calls a bed) that lay longitudinally along the ship’s axis. It takes heavy weather to make a 100,000-ton ship move and when we were sailing through a storm, my bunk would rock me into a magnificent slumber.

On a particular set of nights in the Western Mediterranean in early 1987, I was able to listen to a lullaby of our escorts’ bow-mounted SQS-26 sonars pinging through the water and the steel of our hull while we passed through a winter storm. It was pure heaven!

As I described above, all of this would change when we joined the brand new Theodore Roosevelt. I would never again enjoy the steel sanctuary and sense of a familiar old friend that the Nimitz was.

I miss her.

Surprisingly, during the two cumulative years I spent at sea over a four-year period, my carrier only went to General Quarters (GQ)—or battle stations—one time. Aboard the Theodore Roosevelt, we had a fire erupt in the auxiliary diesel engine room. The fire was quickly contained and put out by the outstanding Damage Control (DC) teams. Our blackshoe brethren were, for the most part, despised by the brownshoes—or aviation Navy—and vice versa. We rarely appreciated how often they saved our asses.

All of our other GQs were only exercise or training events. We used to have a standard joke: “When the carrier goes to battle stations, the air wing goes to bed”—or hides in our respective ready rooms. It was a pain in the ass to move around the ship since everywhere you went you technically had to get Damage Control (DC) Central’s permission to move and all the hundreds of water-tight doors were dogged down. If you did venture out of the ready room on your way to the flight deck to fly a mission, you had to step over members of the DC teams that were spread across the carrier on every deck.

Now, years later, and in light of what the USS Stark, Samuel B. Roberts, Cole, Fitzgerald, and McCain have suffered, I deeply regret not participating in these evolutions with the DC Teams. Had we collided with another ship, or received actual combat damage aboard my two carriers, we in the air wing would not have been prepared to help save our boat—just as the major carrier fires aboard USS Forrestal, Oriskany, and Enterprise had confirmed.

Overall, life aboard an aircraft carrier was incredibly generous and, despite our bitchin’ while at sea, it was a truly fortunate experience for those of us who were aircrew.

The Viking’s Shadow

I left the Navy before I had a chance to see one of the two most successful variants of the S-3, the ES-3A Shadow. It was my understanding that, at the time, you had to have a Top Secret (TS) clearance to simply climb up inside her cockpit. The vast majority of AWs only had a secret clearance until a TS became mandatory in the early ‘90s.

My one connection with this mysterious aircraft came when I was an instructor. Since no Shadow airframes were available at the time, the first class of enlisted backseaters needed to be trained in emergency egress procedures, inflight safety, and the operation of two of the sensors that the ES-3A would retain from her first life as a Viking – the APS-137 radar and the ESM suite. After classroom training, we took each of them on a single familiarization hop in the backseat of one of our S-3Bs.

Because of my lack of experience with this beautiful mutation of the Viking family—I’m a sucker for airplanes with all kinds of tumorous growths on them—I have to rely on the always-excellent work done by Squadron Signal Publications in their book S-3 Viking In Action by Brad Elward. His section on the Shadow is probably the best available. I highly recommend this particular text for its collection of magnificent pictures and outstanding info contained within a very short 80 pages.

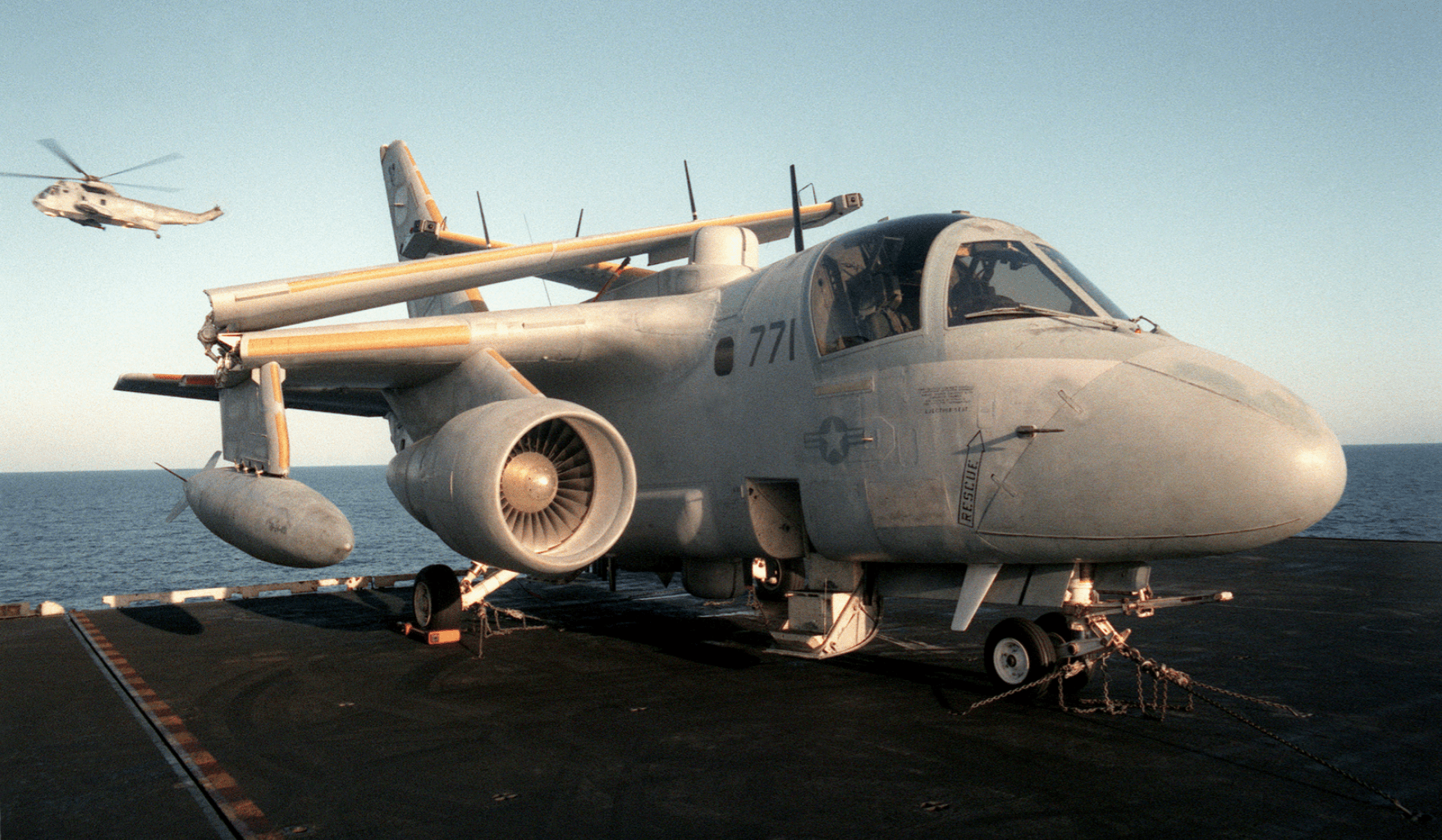

Actually, I just missed seeing the ES-3A by a few months since the USN chose to do field conversions at NAS Cecil Field instead of at the Lockheed plant. Sixteen Viking airframes were chosen to morph into the Shadow. While the basic bones remained, it was quite obvious that she was nothing like her old ASW/ASuW [Anti-Submarine Warfare/Anti-Surface Warfare] self.

The Navy decided in the late ‘80s to end the long career of its only carrier-based signals intelligence (SIGINT) aircraft, the EA-3B “Whale.” They didn’t have an immediate replacement but Lockheed offered their concept of the ES-3 to replace the ongoing need for the gathering of electronic intelligence (ELINT) and communications intelligence (COMINT) for the battlegroup. The USN accepted the concept and awarded the contract.

The Navy, which loved to tinker with aircraft already in its inventory, was wooed by Lockheed’s major selling point: the Viking’s airframe had proven itself inherently stable and reliable over the previous decade and a half. That foundation allowed for non-disruptive modifications, such as the removal of the sonobuoy chutes and the MAD [magnetic anomaly detector] boom.

Of course, the nature of the Shadow’s missions required significant additions of displays, devices, and the black boxes that ran them. Space inside the aircraft was carved out for these critical boxes with the removal of the acoustic processing equipment, which took up most of the left side of the avionics tunnel. However, it wasn’t near enough room.

More carving took place in the weapons bay, where a full suite of electronics replaced the space normally reserved for torpedoes and bombs. This exponential increase in electrons and heat would require an even better cooling source than what the original Viking design offered, so a vapor cycle system “was installed to provide air conditioning for the new electronics in the bay and to sanitize moisture and salt from the aircraft to reduce corrosion,” writes Elward. Her ESM was upgraded as were her communications and navigation capabilities.

The old GPDC was replaced with not one, not two, but with three computers. Elward continues: “Finally, the Shadow incorporated the Multi-Static Processor (MPS), which gave the ES-3A a passive airborne exploitation capability in the same league as the larger EP-3E and RC-135 Rivet Joint.”

The crew changed as well. Instead of the Viking’s three officers and one enlisted aircrew, the Shadow had a pilot who was the Electronic Warfare (EW) mission commander and an NFO (Naval Flight Officer) who was the EW [Electronic Warfare] Combat Coordinator (EWCC) upfront.

Behind the front seaters, two enlisted aircrewmen occupied the rear cockpit. If the mission was primarily COMINT, a Naval Aircrewman qualified as a cryptologist technician (CTI) would fly. If it was primarily ELINT, an EW Operator (EWOPS) would occupy one or both of the rear seats.

The addition of all the bells and whistles came at the cost of 4,000 additional pounds, making the aircraft considerably more sluggish. Regardless, the ES-3A performed her SIGINT missions for the CSG commander and was called upon to execute additional tasks, such as Overland Battle Damage Assessment (OBDA) and Over-The-Horizon Targeting (OTH-T), all-the-while keeping the air wing in the gas by retaining her much-needed tanker capability.

Another critical mission that the Shadow performed for the CSG was assessing combat electronic order of battle (EOB), in which threat emitters and other enemy RF [radio frequency] sources would be categorized, mapped, and potentially exploited by the CVBG.

Elward describes just such a mission:

Typically, Shadows flew missions at high altitudes at long standoff range gathering information about enemy air defense networks, listening to communications, and helping identify and classify potential targets. Shadows often worked together with S-3Bs to create an overall EOB.

Due to the limited number of ES-3As in the detachment, Shadows would often fly a mission along a designated route, followed by an S-3B Viking using its ESM suite and then compare data obtained from the two flights before making a second Shadow flight where the ES-3A would fine-tune the observations.

The Shadow joined the fleet in 1992, with the birds going to one of two squadrons on each coast of the US. Fleet Air Reconnaissance Squadron (VQ-5), the Sea Shadows, was established initially at Guam and later was transferred to NAS North Island in 1994. In April of 1993, VQ-5 made the first operational deployment of the ES-3A aboard USS Independence. The east coast stood up VQ-6, the Black Ravens, at NAS Cecil Field with the first deployment aboard USS Saratoga in January of 1994.

The ES-3A Shadow flew operationally, including working with NATO operations in Bosnia, until 1999 when “costs and budgetary constraints” ended what should have been a remarkable aircraft’s long career. With its loss, CSG commanders would have to rely on land-based EP-3E assets and USAF aircraft to meet their ever-increasing SIGINT needs.

The Shadow airframes, now joined by their Viking kin, rest on a plot of desert Bone Yard in a world no longer at peace. Once again, one has to question the USN’s decision-making process and lack of foresight. Of course, budgetary myopia seems always to trump common sense, simple wisdom, and the unheeded lessons history keeps trying to teach us.

Miss Piggy

Obviously, with the transition from the propeller-driven S-2 to the jet-powered S-3 Viking, the C-1A Trader variant of the Tracker that served as the primary Carrier Onboard Delivery (COD) aircraft would have to be replaced, as well. Lockheed, seeing a chance to take a chunk out of Grumman’s dominance of carrier deck space which included the C-2A Greyhound, offered a variation of the S-3 airframe. Surprisingly, the USN awarded the contract in 1975 for six US-3A CODs.

Lockheed decided to make use of the seventh YS-3A airframe, stripping out all mission electronics. Since no passenger-now-prisoner of a crashing airplane would be pleased with having their flight crew leave them behind via pyrotechnics, the Viking’s four ejection seats were removed.

In their place, a pilot, co-pilot, a loadmaster, and up to six rear-facing passenger seats were installed. Cargo space was carved out of the weapons bay and two big cargo-carrying blivets could be slung under each wing station in place of fuel tanks. In lieu of passengers, additional cargo could be carried internally for a total capacity of 7,400 pounds. However, the addition of the blivets reduced her range from 2,700 nautical miles to just over 1,900 nautical miles, which was still very substantial.

Was Miss Piggy, as her crews and the fleet affectionately called her, a worthy replacement of the Trader? While the C-1A could carry up to nine passengers, it could only carry 3,500 pounds of cargo. As I mentioned above, the USN already had a COD aircraft, a variant of the E-2 Hawkeye. The C-2 Greyhound became operational in 1965, a full decade before the Viking variant contract was awarded. Its two Allison T-56 turboprops could haul 10,000 pounds of cargo, including outsized aircraft engines, personnel, and most importantly to the CVBG sailor, mail. Clearly, the Greyhound could do the job better.

So, why did the USN choose to utilize Miss Piggy? I really don’t have a clue. Add to the mystery that the US-3s were limited to the west coast Navy and flew only in the 7th Fleet area of operations out of Subic Bay in the Philippines or Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean. Also, the only squadron that flew the six aircraft was the Foo Dogs of VRC-50—“VRC” being the designation for Fleet Logistics Support Squadron. When I find an answer as to what the Navy was thinking with the US-3A, I’ll let you know.

A Premature Demise?

A couple of times a month I’m asked if the decision by the U.S. Navy to retire the S-3 Viking in 2009 was a mistake. One conclusion I have drawn, while mulling over this critical question, is that there is a far more important consideration that is essentially ignored: “Was the resolution to remove the SENSO and the ASW mission equipment for which the Viking was originally designed, a fateful miscalculation?”

This move, made nine years prior to the aircraft’s retirement, was symptomatic of the utter failure of the Navy to stay the course after the end of the Cold War on what arguably was and is its most important mission—anti-submarine warfare.

Okay, so I got that small measure of bitching off my chest. Now, onto the larger issue of retiring the aircraft altogether. Was it a mistake for the Navy to do so? Should it bring the S-3 back to be a tanker and perform other missions? Are current ASW measures enough to protect the Carrier Strike Group (CSG) and Expeditionary Strike Group (ESG) while performing the other ASW missions necessary to meet the “new” threat posed by the Russians, not to mention the Chinese—a threat that is relatively new but not unexpected?

First, let me acknowledge just how ignorant the empowered minds had to be not to have seen how many hats the Viking had worn, and how many variants were theorized and produced from one, single, brilliant airframe. Of course, the ignorant aren’t completely to blame. The VS [air anti-submarine and sea control squadron] community had decades to develop a reputation, as the VP [patrol squadron] community did, and lobby for the life of the S-3. Our subordination in the air wing didn’t have to be an accepted limitation.

Now, in a world filled with contradiction, allow me to add one of the many I own:

It was a mistake to retire the S-3…and…it wasn’t a mistake.

It wasn’t, because at the time it did make fiscal sense – that is if you subscribe to the group who were quite certain that the end of history was upon us and we would all live happily ever after. However, Desert Storm, Bosnia, Somalia, and the planet changing effect of September 11th made it quite obvious that happily ever after is found only in naïve minds and fairy tales.

Yet, less than a decade after the same euphoric thinking that pulled the SENSO out of the Viking reared its ugly head and made the myopic choice to remove the aircraft from fleet inventories altogether. That thinking failed to consider, with one eye in a history book, what was really going on in the world and how removing a critical in-flight refueling asset would affect the only strike mission aircraft left on the carrier’s deck.

The Navy bought into the concept that there would always be a USAF tanker ready for the air wing to plug into, no matter where the carriers were in the world. This is the same thoughtless argument that believes a P-8 will always be overhead to protect every CSG and ESG while still having plenty of airframes to perform open ocean search and tracking of subsurface threats that, in the 21st Century, have slipped away from our convenient assumptions of how they’re supposed to behave. That’s not to mention the numerous other missions expected of the Poseidon.

A word about the P-8 and availability. Back in the day, if there was a potential submarine threat, VP (P-3 Orion squadron) support of a CVBG was mostly requested at night unless we were in a major ASW exercise. CAGs and carrier COs preferred daylight cyclical ops and needed the overnight time for maintenance and to rest their catapult and arresting gear crews.

Because submarines never get the memo about the carrier’s preferred schedule, they tend to attack at all hours. Thus, it was painful getting the CAG and CO [commanding officer] to support 24-hour or “flex deck” ops allowing the S-3s, an E-2, and the helos to launch and address the all-hours schedule of the enemy submarine. Now that there are no fixed-wing ASW assets aboard the carrier at all, so the need for the P-8 has risen dramatically.

A quick comparison is in order. Open source info tells me that a P-8 will be on station between four and six hours per mission depending on transit time. Also, according to data published in 2018, the U.S. Navy is planning on acquiring 117 Poseidons to handle the issues faced by a four ocean Navy that has to constantly attend to several seas and a troublesome Persian Gulf. Again, back in the day, at the height of the 1980s, there were 377 Orions spread across three oceans, several seas, and an increasingly disturbed Persian Gulf. The P-3 also tended to stay on station for an average of eight hours.

Granted, as the open-source materials state, the P-8’s acoustic suite and sonobuoy load are significantly better—and they damn well better be—than what came before. I’ll also give you the 60 or so MQ-4 Tritons drones if you’ll assure me that they can meet the tactical ASW needs that will haunt CSGs in the decades to come (they aren’t really an ASW platform). Thus, when I do the availability math, taking into account all other sources of intel and ASW support…well…I’m worried.

I’m sure you’ve heard the saying “generals and admirals are always fighting the last war.” Well, we are confronted with a new Cold War with a decidedly 21st Century flair while preparing for the Cold War of the 20th Century without the funds and assets we used to dominate and win that one.

Have I told you, lately, that I’m worried?

Should the Viking, then, be brought back into service? No. It’s too late for the USN. That decision should have been made and acted on by wise minds a few years after its retirement as the Navy witnessed how much wear and tear tanking contributed to the life expectancy of the Super Hornet. They should have stripped the airframe of all of its electronics, save the radar and ESM, and filled all the available spaces with gas. But, as many rightly point out, bringing the Viking back would become a fiscal nightmare because of the well-documented propensity of the Navy to add on all kinds of bells & whistles to fulfill every need they perceive the airframe should meet…including fixed-wing ASW.

Now, let’s look at other ASW assets around the CSG in light of the Viking’s absence. There is the belief that all carriers have a nuclear fast attack submarine (SSN) supporting their deployment. Sorry, but here we go again with availability. That was nominally true during the latter part of the Cold War, but the number of Virginia class boats available today and in the foreseeable future don’t add up to the wide-ranging, burdensome needs now placed on the submarine community.

What happens if there is a war with China and Russia supports their communist acquaintance? Let’s be honest, there is a desperate need for the primary missions the SSN fulfills, not to mention the need to keep pace with the steady growth of the worldwide diesel submarine threat and the intel gathering that is needed to understand what makes the Chinese Navy and others tick. And the SSN is still our only reliable asset in the Arctic even as seasonally navigable waterways open up for longer periods. Remember, along with the White Sea, this region still remains the safest place for Russian SSBNs to hide if we get into a protracted shooting war with that country. And if we do, those SSBNs have to go.

The surface navy is finally getting its ASW act together. In light of their self-imposed lack of simple sailoring skills, I really hope they are. The reality? Even if they were at the top of their game today, only having two or three destroyers protecting a CVN simply won’t be enough to meet the submarine threat. There have always been and will always be too many variables in hunting submarines that will quickly deplete the capabilities of two or three surface warships.

Finally, the helicopter.

I will always remind anyone who asks how two or three helicopters with dipping sonar are the very best air ASW threat to a submarine. However, let me qualify that statement with the fact that this is true only after the submarine has been localized.

For these helos to be effective, the submarine’s general location must already be known, and in today’s and tomorrow’s environment, just like during the Cold War when we had assets a-plenty, a flaming datum may be the only way an initial detection is provided. Simply put, helicopters, by themselves, are not very good search platforms. Unless things have changed, a helo with a dipping sonar brings nothing to an initial search that the carrier’s escorts don’t already provide with their bow sonar in active mode—it is a waste of fuel, of crew endurance, and system use.

Once a potential contact has been gained, then the helo is the ideal sub-hunting platform. A sonobuoy search by a helo is also a waste since only a relatively small number are carried and the helo’s range and relatively slow speed prevent it from meeting the typical demands of the search phase of ASW. Oh, and there simply aren’t the numbers of helos aboard the ships of a CSG to perform all the missions expected of them while also performing a very time-consuming blind search.

The helo’s range and speed actually pose a major threat to the carrier. The presence of an ASW helicopter not only informs a submarine skipper that there are major warships present, but ensures that they are close by. Not having any ASW sensors or weapons aboard, the carrier’s only self-defense against a submarine is to run away at relatively high-speed.

While maritime geography and operational needs may tie an aircraft carrier to a certain, vulnerable location, her deployed helicopters hunting a submarine place additional leashes on an already exposed capital ship. The carrier must stay within the limiting range of its helos to ensure they can be safely recovered.

I love helicopters, but in the current ASW environment, just one potential submarine will sponge away all available ships, aircraft, and sensors. When the second and third possible submarine contact is detected, God help the ASW commander.

The loss of a sea-based fixed-wing “outer-zone” ASW aircraft has taken the USN back into the 1940s and 1950s where, in the vast majority of instances, they were forced to wait for the submarine to find them. If we are faced with a naval conflict against China and/or Russia, whether brief or protracted, the fog and chaos of war will exponentially add insult to the injury of “never enough assets” and create far too many flaming datums.

Oh, and the real irony of today’s CSG? There is plenty of deck space these days for 10 Vikings on the supercarriers with their shrinking air wings.

If I may: Laugh…out…fucking…loud!

Here’s how I see it:

The Navy needs to gradually move away from total reliance on manned aircraft and begin to fill the decks of every ship in the Fleet, including auxiliaries, with all manner of unmanned air/surface/subsurface vehicles capable of performing each mission in any electronic environment. The irresistible movement toward this era of unmanned warfare is upon us whether we like it or not. We have, and will have, the technology to not only create various types, shapes, and sizes of sensor/weapon-carrying vehicles, but to employ them in the battlespace that is being created by this era. Most importantly, and for the moment, it is a field of play where we, our friends, and our enemies are all new to the game.

We need to move in this direction because every sea environment we enter will soon contain multiple subsurface threats of varying complexity. The CSG going through a choke point will not only face one, two, or three manned submarines in a layered defense, she will also face many mission-critical unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) that will accompany those submarines. Some of those UUVs will also find employment as decoys providing an almost perfect simulation of the host submarine’s acoustic and performance profile. Now, you have seven…no, 11 contacts!

So, here’s my worried question:

Are we even training for this environment today? Does the acoustic sensor operator in the MH-60 and P-8 know how to detect, classify, and track a UUV? Does a surface ship sonar tech have the know-how? At the very least, they damn well better be training the sonar techs who serve aboard submarines to do this.

Instead of dismissing the navalized unmanned concept as “naive at best, delusional at worst,” we need to have the courage to accept that this is the natural evolution of naval warfare. After all, just a century ago the battleship admirals thought the same of the airplane and submarine.

No Foreign Viking Adopters

I am very disappointed that the Viking fleet continues to languish in the desert since its retirement. As I stated, I don’t think they are relevant to fulfill USN needs. However, I am surprised that Singapore, South Korea, Vietnam, or even Australia haven’t purchased a clutch or two of them.

The Viking’s range and endurance are perfect for the maritime geography that surrounds these countries. There is no question that Australia, for example, needs the P-8. However, they are costly and our good friends can only afford a limited number. Using an Aussie S-3 to cover her green and brown water would be a tremendous reduction of the burden a Poseidon-only fleet will have to carry.

Despite arguments to the contrary, the Viking still has plenty of life in her and nations that would be able to use them wouldn’t be subjecting the airframes to the harsh aircraft carrier environment. The aircraft would make fantastic littoral MPAs (Maritime Patrol Aircraft) and with affordable non-acoustic and acoustic system/processor updates, could handle diesel, nuclear submarines, and UUVs with relative ease.

Is The Aircraft Carrier Still Relevant?

There’s a quote in my notes somewhere that argues against the aircraft carrier as being far too vulnerable in “modern naval warfare.” The quote is from an article written in…wait for it…

1922.

Submarines have proven that carriers, and all surface ships for that matter, are vulnerable. Airplanes have proven that aircraft carriers are vulnerable. Very angry anti-ship cruise missiles, and now anti-ship ballistic missiles, have threatened the survivability of the carrier. But in any argument against or for the aircraft carrier, many factors come into play, the least of which is defining what vulnerability and survivability actually mean. And let’s face it, warships of any type at any time in history have always been vulnerable.

One thing that needs to be recognized is that the majority of folks who emphasize the vulnerability of the aircraft carrier are also arguing about the incredibly high cost of building and operating them, and they are absolutely correct and right to do so.

I’m torn by all sides of the argument having served aboard Nimitz and Theodore

Roosevelt during the aircraft carrier’s glory days.

Degrees of carrier vulnerability have come and gone and come back again over the aircraft carrier’s century of existence. World War II showed how easy it was to sink them and how difficult it was. The examples set by the USS Forrestal, Enterprise and, to a lesser extent, the USS Oriskany showed how a carrier can survive conventional weapons explosions and resulting fires due to the persistence and sacrifice of damage control teams and the dedication of the ship’s crew.

As opposed to land bases, the aircraft carrier is highly maneuverable and can take itself out of potential danger, or not go in harm’s way at all. The battlegroup commander can also pick and choose the level of risk he or she is willing to place their high-value assets in. Visual, electronic, and operational deception still works. The oceans and seas remain very large places to hide in despite modern technology.

But things, they are a-changing.

No one knows how effective Chinese anti-ship ballistic missiles will be against the aircraft carrier. Have they perfected the targeting and maneuvering required to hit such a dynamic target? That is once they’ve found it? Do they have the resources and stamina to go after more than one carrier?

Certainly, they invite capitalization of the carrier’s vulnerability if they pick and choose where the fight is going to be. If they get one carrier, will it escalate into a tactical nuclear war? Will it go further than that? Are they even afraid of this possibility in light of our current nuclear weapons theory and practice?

And that leads to the “newest” problem faced by our current carrier fleet: area denial weapons being developed and utilized are, in theory, pushing the aircraft carrier further and further away from the potential fight and we aren’t helping the matter. By placing manned aircraft on the deck that have less and less range to do the traditional missions of the aircraft carrier, we are supporting the effective, fear-based tactic the Chinese are currently using with the deployment of the anti-ship ballistic missile and far-ranging air defense systems.

One solution that has been argued for decades is to stop buying the supercarriers and start buying smaller ones. It is an important argument simply because the more assets you have, the more your enemy will face. But “smaller” invites a host of problems of its own to be dealt with. Reduced deck space limits the number and type of aircraft that can be flown off on missions. How is the smaller carrier powered? If it is conventionally powered, then you have to drag around more auxiliaries to ensure your higher number of carriers have the supplies, fuel, and gas they need. More carriers also need more crew, which means higher costs in manpower—one of the more expensive aspects of any military force.

Today, the biggest problem with the larger number of small carriers argument is that anything touched by the military and industry mutates well beyond the original intent of design and cost. This frustrating neediness for all the latest “upgrades and apps” and a pathetic obsession with greed ends up bringing the costs into the neighborhood of the supercarrier. Meanwhile, we end up having ships originally designed to perform three missions, unable to perform any of the 32 missions we’ve added on.

I love the concept of the smaller carrier. In my thinking, I believe it can work…but I also suffer from a case of severe nostalgia.

In all honesty, I really don’t have an answer because there are so many factors and scenarios to consider. The aircraft carrier has served the United States very well as the peace-time political tool needed for influential diplomacy and power projection. But so was the battleship up until 1939.

In past wars, up to Desert Storm, aircraft carriers performed brilliantly. To meet the challenges of the rise of the Soviet Navy, particularly its submarine force, the aircraft carrier evolved and rolled very well with the punches. Today, the flat top remains, essentially the same; however, its actual weapon, the manned aircraft, has changed…for better?…for worse? As it has been said, repeatedly: a carrier’s true vulnerability relies on the range of its aircraft. Let’s hope the Super Hornet and F-35’s limited range can be “extended” by its amazing 21s Century capabilities.

And now, ladies and gentlemen, we have hypersonic weapons…

As a nation, we need to take the question of the future of the aircraft carrier seriously and find effective answers before one of those huge, nearly irreplaceable, intensively manned, and very costly assets meet their ultimate humiliation at the hand of a non-peer or peer state.

Maritime Patrol In An Age Of Advanced Air Defenses

The four nautical mile range ring.

A seemingly benign symbol that surrounded another seemingly benign submarine symbol on our screens. Placed there by Viking TACCOs [Tactical Coordinators], it had begun to strike fear in the hearts of Viking crews in the 1980s and early 1990s. Our sense of invulnerability was coming to its end.

Just remember, if you penetrate that circle, our Intel Officer admonished, you’re as good as dead!

For most of the Cold War, the MPA and carrier-based ASW community flew with impunity in the skies around and above surfaced and submerged submarines. As World War II ended, deck guns were being traded for hydrodynamic sails and casings because, in a hostile environment, the submarine didn’t need to surface any more. All she had to do was stick her snorkel up to charge her batteries. Thus, we had no immediate threat to hinder our ability to perform our mission and stay close to the submarine. We did not have to fear AAA [anti-aircraft artillery] or SAMs [surface-to-air missiles] coming up from our targets simply because the stealth theory dominated the submariner’s mind. They preferred the depths. But then, somebody decided enough was enough: ASW aircraft had had far too much freedom.

Four nautical miles…

Today, MPA aircrews face range rings in the scale of hundreds of miles, depending on where in the world they are flying. Layers and layers of weapons-plus-geography are now being built in what appears to be our most serious theater of maneuver and warfare: the East and South China Seas.

The Chinese played the role of student during most of the Cold War. They watched. They learned. The 20th Century has been an interesting and powerful classroom for them.

With the fall of the Soviet Union and their own tremendous economic growth, they believe they’ve graduated and feel that the 21st Century belongs to them.

They may not be wrong.

One significant lesson they’ve learned from the US is the importance of dominating their hemisphere. Within that geographic hegemony, they are placing weapons such as the HQ-9, a variety of fighter aircraft with long-range air-to-air missiles, electronic air defense stations, and various anti-ship missile systems to prevent easy access to their overall strategic plan.

In theory, these systems will push warships and aircraft carriers back beyond their effective ranges and threaten the bases and governments that allow allied MPAs and other, critical land-based assets to freely and easily perform crucial missions.

At least in theory.

In a world where technology demands a multi-platform approach to warfare, the MPA may not be able to penetrate the layers of defenses offered-up by the Chinese. Thus, we have to design and develop a new way of penetrating these defenses just as, in the past, every new weapon, tactic, and strategy was countered by another new weapon, tactic, and strategy.

In the interim, there is good news—the Chinese can’t do this all at once. It will take time and we need to take advantage of that time. Also, as Tyler has pointed out, most recently in his Saudi oilfield attack, having the best air defense system doesn’t mean it’s going to work as advertised. While the Chinese are outstanding students, they haven’t fought a naval engagement or war since the late ‘70s, whereas, we have been on a war footing since 2001. And one of the greatest truths of warfare is that the defenders of any plot of land or area of the sea tend to fall into a malaise brought on by a false sense of security and superiority.

Even better news—unlike the neighborhood in our hegemony, China’s neighbors don’t trust her, and Japan, Vietnam, and South Korea hate her, and are arming themselves to deal with her. Also, China is primarily interested in her global status as an economic power. It’s not about philosophical domination…just economic. Once she leaves the bastion of the East and South China Seas, she becomes just another blue water navy.

There’s an old saying that is a profound truth: “Train like you fight; fight like you train.” MPA crews are going to have to continuously educate themselves on the Chinese theater of operations and train for the realities they will face. The men and women who man the P-8s, P-1s, P-3s, and other MPAs in the region need to speak up and offer ideas, concepts, and tactics to senior leadership about how they need to fight since they are the ones who are, and will be, actually doing the fighting. They just can’t rely on a playbook written by those who aren’t, or worse still, those who are preparing to fight the last war. The aircrewmen need to analyze and innovate about how to crack the Chinese shield and get in to perform their ASW and ASuW mission…and then get out alive.

Being The Guy In The Back

If I may, a word to any of you out there contemplating military aviation who are already bespectacled, don’t have a four-year degree, or have been told by a recruiter that you won’t make the pilot-cut:

There is a reason that certain airplanes have more souls on board than that one guy who is pushing rudder pedals and flipping ailerons.

That reason is that those airplanes are designed to do a mission only additional crewmembers can successfully complete. Despite not being the stars of Hollywood movies, the NFOs, WSOs, EWOs, AWs, SAR swimmers, boom operators, and yes, even loadmasters, complete the vital fabric of a complex and powerful weapon system.

I mean, let’s face it, the only reason we remember Anthony Edwards’ character “Goose” is because he is a brilliant actor and was funny as hell in Top Gun. Some other RIO stunk while poor, helpless Mav got yelled at by a really cool RIO who wore a really cool VF-111 helmet.

It is worth pursuing, but it will cost you.

If I may offer some advice:

You have to become an expert at your job. Not only developing technical expertise, but a complete immersion into the tactics, the issues, and histories of the seat you’re occupying. Take advantage of every peripheral job, class, and opportunity that allows you to learn more about your weapon system and how it fits in with others within your own branch and all others of the US and Allied militaries.

Also, and this is crucial, become the subject matter expert on the enemy you will face.

You’ll be crewed with some very strong egos, which speaks to the need to come to the game with a strong sense of humility and a strong understanding of the purpose of your mission. Also, you will have to “grow a pair” in order to handle a world and attitude that subordinates you while happily glorifies the pilots. In many ways, like ole’ Goose, you’ll have to mother your pilots, and with larger crews, you’ll have to be a den mother.

I had the honor of flying with some genuinely amazing NFOs who took their job very seriously and were also fantastic, humble human beings. Many of them admitted in our cockpit confessionals how they wanted to be pilots, but for various reasons didn’t make the cut. Instead, they motivated themselves to be the best and counted themselves fortunate to be crew members in an environment where history is made and every single day matters. Several of these tremendous souls went on to command S-3 squadrons, and one or two went on to skipper an aircraft carrier.

One guy, Lieutenant ‘H,’ who was my all-time favorite division officer and a magnificent COTAC/TACCO, decided to change horses in midstream and become a SEAL. He was warned by the ‘upper management’ that his naval career was over. He didn’t care, he wanted to swim, jump out of airplanes and do neat shit every damn day.

A year or so after he left, we actually called him one morning and you could hear the smile pulsating in his voice. After catching up, he said: “Boys, I just got back from a shooting exercise; good talking with you, but I gotta let you go because I’m off for bit o’ lunch and then a HALO [high-altitude, low-opening] jump out of a COD!”

I recently read where he had retired a few years ago…at the rank of Captain with NFO wings and SEAL trident adorning one helluva naval career.

Any branch of the military offers a universe full of opportunity and adventure. If you involuntarily (or voluntarily) decide to sit in the backseat of any aircraft, every day can be a treasure waiting to be unearthed—even those periods of time that will seem unbearably boring—and you will be blessed with plenty of those days. Most importantly, you will be given the opportunity to grow as a human being and become a leader, two qualities that will serve you well for the rest of your life.

The challenge, however, belongs to you to make the very best of it.

Two additional things. First, find a mentor and then be a mentor. Be a mentor even if your charge doesn’t want you to be there for him or her.

But most of all, keep a photographic and written journal of each and every day of your life. I have lamented over and over again about the dearth of pictures that I have after being in the USN and flying in and working around some of the most historically awesome aircraft and warships the world has ever known. My pathetic handful of images haunt me every day.

However, the most powerful specter has been my failure to write a detailed account, each day, of the things I encountered, experienced, and did. I’ve missed so many precise dates and explanations of events that I’ve related to you here and elsewhere because I just simply didn’t write them down.

There are other events I’ve wanted to tell you about, but have had to exclude them because they are lost in the fog of time-past. In my research, I’ve encountered several pilots, who have briefly annotated notes in their logbooks describing what each particular flight accomplished. Why? WHY didn’t I think of that?!

Please…PLEASE! WRITE!

Looking Forward

I’ve enjoyed this journey back into all-things ASW, submarines, naval aviation, and Cold War history. It has sparked a passion within that I didn’t think I could find.

Partial blame goes to Tyler and you guys for that fateful day I stumbled upon Foxtrot Alpha in April of 2015. I was introduced to a community where the writer loves all-things military tech and is in love with military aviation while being stalked by an informed, witty, snarky, and faithful group of readers, detractors, stalkers, and bots whose comments and feedback are truly second-to-none. But it was Tyler’s article in September of that year on the possibility that South Korea might purchase a few Viking airframes that enlightened me to a hunger out there for the amazing history and stories of the great souls who created, developed, and operated the weapons and systems that have fought for an always-tenuous peace.

Another important place for me has been Twitter. Like TWZ, I have been away from there far too long and look forward to making more time for posts and conversation. I have had the honor of encountering a world of people who appreciate an unamended picture of a Cold War airplane, warship or submarine. It has been such a powerful experience to receive responses from the vets that actually served aboard them back then.

I have been genuinely humbled by the kindness of those individuals who have befriended me…particularly an old RC-135 driver, a couple of Royal Navy submariners and skippers, some authors and writers, and a former Soviet Naval officer, who I hope Tyler interviews someday.

I also received a gift of a private memoir from one of the Royal Navy’s nuclear submarine skippers who fought his boat during the Falklands War. It is a treasure I keep close to me and will carry it with my ashes, one day, on that final journey back to the sea.

I have decided to slowly, but fully pursue a long-lost love of mine—writing. As an airborne ASW operator, I stood on the shoulders of some tremendous souls who designed, developed, and flew the history that prepared me to perform my late Cold War mission. Their stories and the stories of their stunning creations need to be told.

Along with writing several histories related to Cold War ASW, I’d like to take a crack at naval fiction. Between now and then, in an effort to bring my writing up to par, I’m working on a variety of articles covering a wide range of popular as well as obscure subjects. In my reading, I’m encountering tremendous things that have happened that are lost to history and deserve a second look.

I am deeply grateful to Tyler for giving me this opportunity to spill some of the beans and your willingness to read it. All of you here at TWZ mean more to me than I can articulate. Thank you all for allowing me to reminisce.

In case you missed it, you can read the other three parts of the Confessions Of An Ancient Sub Hunter series linked in order here, here, and here.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com