A fisherman in Indonesia, referred to only as Saeruddin, recently brought in a very different kind of haul, catching what appears to be a Chinese underwater drone. At least two other very similar, if not identical ocean glider-type unmanned undersea vehicles have been found in Indonesian waters in the past two years. This raises questions about whether the Chinese government is discreetly conducting underwater surveys of routes between the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, information that could be especially useful for its submarines transiting through these areas while submerged.

Saeruddin reportedly nabbed the drone on Dec. 20, 2020, near the Selayar Islands, an archipelago that is part of Indonesia’s South Sulawesi province, in the central part of the sprawling nation, which consists of more than 17,000 individual islands. He subsequently handed it over to local police, who then turned it over to the Indonesian military.

A report from Indonesian outlet detikNews said that the drone, which had what appeared to be some kind of sensor array in its nose, was just under 7.4 feet long, not counting what appears to be a long antenna or sensor extending from the rear end. Pictures of the unmanned undersea vehicle (UUV) show that it has a torpedo-shaped body with a pair of wings mounted toward the center and a vertical tail.

Twitter user @Jatosint was among the first to note the strong similarities to the Sea Wing UUV, a design developed and produced by the state-run Chinese Academy of Sciences’ (CAS) Shenyang Institute of Automation and that has been in use since at least 2014. An ocean glider-type underwater drone, Sea Wing moves forward in the water, aided by its wings and tail, by repeatedly diving and then surfacing again. It performs these maneuvers using an internal system, essentially a balloon that expands and contracts as pressurized oil moves in and out, which alters its buoyancy.

China has made questionable claims in the past that Sea Wing drones have been able to remain at sea for more than 30 days and dive down nearly four miles below the surface.

CAS publicly uses Sea Wings for oceanographic research with sensors capable of measuring things such as the strength and direction of currents and water temperature, oxygen levels, and salinity. These are common tasks for these types of UUVs, which are in use around the world, including by military forces.

In December 2019, the Chinese survey ship Xiangyanghong 06 launched 12 of these UUVs into the Eastern Indian Ocean. CAS said the group of drones ultimately traveled more than 12,000 kilometers, or 7,500 miles, collectively. Chinese authorities did not report any of the drones going missing, but it is worth noting that initial reports said that 14 of the drones, rather than 12, had been deployed. At the same time, it’s not clear if the prevailing currents would have been able to carry a disabled Sea Wing all the way to the waters off the Selayar Islands.

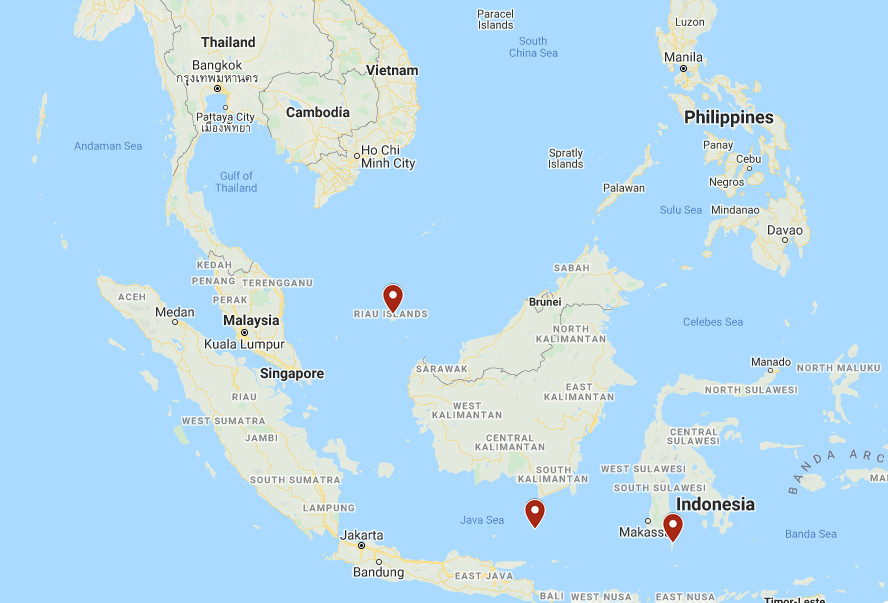

This is not the first time that an apparent Sea Wing drone has been found in Indonesian waters, either. In January, one was recovered near the Masalembu Islands, some 400 miles west of the Selayar Islands. In March 2019, yet another one was found in the waters around the Riau Islands even further to the northwest. These three groups of islands are situated in bodies of water that form important parts of multiple maritime routes that stretch between the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea.

Though we don’t know the exact configurations of the UUVs that have been found in the waters around Indonesia, glider-type underwater drones are also regularly used for conducting hydrographic surveys and otherwise helping with the creation of underwater maps. This kind of information is useful for creating accurate maritime charts to support naval operations, as well as commercial shipping and civilian sailing activities. Having detailed maps of the contours of the seabed is particularly valuable to the crews of submarines sailing submerged under the waves.

As China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) works to project power further and further beyond the country’s coastlines, having up-to-date maritime maps and charts for various critical waterways will be ever more important for both day-to-day activities and any actual future combat operations. The South China Sea is already a hotly contested body of water, with virtually all of the countries in the region disputing Beijing’s expansive territorial claims.

In 2017, there was also a report that the Chinese government was testing how glider-type UUVs, possibly versions of the Sea Wing, could act as communications and data-relay nodes to help rapidly transmit information that might be useful for detecting and tracking foreign submarine movements in the South China Sea. That same year, news had emerged of Chinese plans to establish a network of underwater sensors in that region, ostensibly for environmental research, which could also have potential anti-submarine warfare applications.

While we can’t say for sure what any of these UUVs have been up to in Indonesian waters, suspicions about potential dual civilian and military activities are hardly surprising, either. In fact, a People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) Dalang III class rescue and salvage ship snatched a U.S. Navy glider that had been conducting an oceanographic survey right out of the waters of the South China Sea in 2016, surely in part to try and see if it was actually gathering more substantial intelligence information.

Being able to examine the glider and its payloads could have provided some level of useful information for China’s own intelligence arms. The Indonesian military has very likely been picking over the drones that the country’s fishermen keep recovering, looking to glean any kind of useful details about their capabilities and activities.

As Chinese naval activity through the Western Pacific and out into the Indian Ocean continues to grow, it seems equally probable that these kinds of finds will become more and more common. In 2018, a Vietnamese fisherman recovered what appeared to be a Chinese torpedo, possibly leftover from a drill of some kind, a find that also underscored the increasing PLAN presence in the South China Sea region. In 2015, Chinese authorities themselves announced that a fisherman had recovered what they said was a torpedo-shaped underwater intelligence “robot” off the coast of Hainan Island in the South China Sea, which is home to a major PLAN base.

One has to imagine, if nothing else, that Indonesian fishermen are increasingly on the lookout for more unusual catches in the waters around the country.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com