Russia’s Orion unmanned aerial vehicle has reportedly fired guided missiles for the first time, marking a significant step toward the country deploying its first fully-operational armed drone. As well as missiles, the drone has reportedly also been recently tested with unpowered guided glide bombs. While the Russians have said that the Orion drone — also known by the project name Inokhodets, meaning pacer in Russian — has dropped guided glide bombs before, during combat trials in Syria in 2018, the launch of a powered weapon is a new development.

The milestone for the Orion was reported today by Russia’s state-run media outlet RIA Novosti, which quoted an unnamed “source in the military-industrial complex.” What “small-sized guided missiles” the drone fired in these reported tests were not revealed and it is also possible that they refer to a guided version of the existing 57mm S-5 rocket. This weapon is broadly similar to the U.S.-designed AGR-20A Advanced Precision Kill Weapon System II (APKWS II), which adds a laser guidance kit to the ubiquitous Hydra 70 unguided rocket.

More advanced guided-missile options for Russia’s drones are also being developed by Russia’s Tactical Missile Corporation (KTRV), which produces a wide variety of ordnance for manned combat aircraft. The company is reportedly developing both 110-pound and 220-pound missiles to arm unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Only a mockup of the 110-pound Kh-50 has been seen in public so far.

The guided glide bombs employed in the recent tests could include two different 110-pound weapons that were revealed by Kronshtadt, which makes the Orion, in 2018. These are the KAB-50 and UPAB-50. While the KAB designation indicates a “corrected aerial bomb,” typically using laser or TV guidance, the UPAB designation signifies Universalnaya Planiruyushchaya, or “universal gliding,” and these weapons tend to feature pop-out wings to extend their range.

However, there are other similar weapons available from Russian manufacturers, including a family of bombs produced by the Aviaavtomatika company, which combine different guidance kits and tail sections with warheads weighing either 55 or 110 pounds. These weapons are characterized by their boxy bodies.

Almost simultaneous with the report of the new weapons trials, the Russian Ministry of Defense released its 2021 calendar, which includes a heavily retouched image of the Orion carrying KAB-20 guided bombs — a 44-pound weapon, also apparently produced by Kronshtadt, and which appears very similar visually to Turkey’s drone-launched MAM-L. The laser-guided MAM-L is also primarily designed for use on armed drones and has become a key munition for the Turkish Bayraktar TB2 unmanned aircraft, which has been used to great effect in various recent conflicts, including in Syria and Libya. This combination also saw notable success in the recent conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, a war that we covered in depth in this previous feature.

The launch of missiles, of whatever kind, together with other ongoing weapons trials, would also seem to point toward the Orion moving toward operational capability.

In April 2020, Kronshtadt handed over a first Orion drone system — including three flight vehicles — to the Russian Ministry. At the time, however, the manufacturer admitted that the ministry “had additional requirements that were not originally included in the technical specification.” As a result, the drones had to be returned to Kronshtadt after delivery, and unspecified modifications made to satisfy the customer.

The unnamed source in the RIA Novosti article said that large-scale delivery of the Orion to the Russian military “will restore parity with a potential enemy in this class of equipment,” but the country still lags far behind both China and the United States in developing UAVs of this kind.

With a gross weight of around 2,250 pounds and with an endurance of up to 24 hours, the Orion is somewhat akin to Russia’s answer to the MQ-1 Predator, with which it shares a long, straight wing and a pusher-propeller powerplant. The U.S. Air Force, however, retired the MQ-1 in 2018 and then moved over to the enlarged and more capable MQ-9 Reaper, which has a gross weight of 10,500 pounds. Now, in fact, the U.S. Air Force is looking beyond the Reaper, to the next generation of tactical drones that will replace the MQ-9, as The War Zone discussed here.

While the Reaper achieved operational capability in October 2007, serious work on a Russian medium-altitude, long-endurance (MALE) equivalent to the Predator only really took off after the Russo-Georgian War the following year. To meet an urgent need for a surveillance drone, Russia procured the Israeli-made Searcher II, which it produced under license as the Forpost.

Development of the Orion began in 2011 when Kronshtadt received a research and development contract for the Inokhodets program and a first flight of the drone took place at Protasovo airfield, near Ryazan in central Russia, in October 2016. In November 2019 one of the prototypes was lost in a crash at Protasovo, although the causes of this incident are unclear.

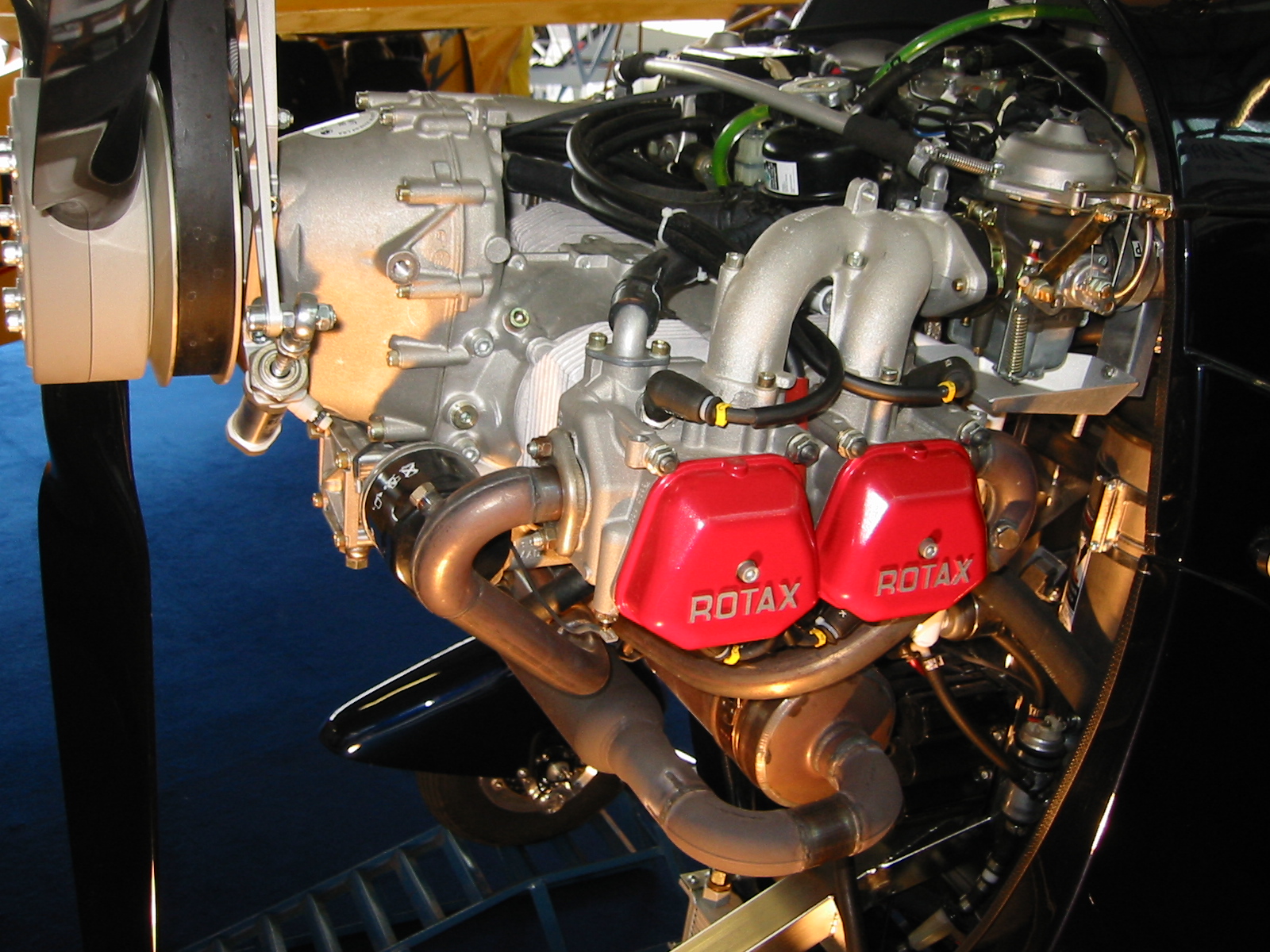

A particular problem faced by the Orion development program has been the lack of reliable powerplant. The original engine was produced by Itlan and was a heavily modified, Russian-made version of the Austrian Rotax 914, as used in the Predator, with an added turbocharger that proved tricky to integrate. While this engine was installed in the first three drones delivered to the Russian Ministry of Defense, an alternative, fully indigenous engine has since been developed by the Agat company and may be installed in subsequent production batches. It is also possible that these engine difficulties are what resulted in the defense ministry demanding the manufacturer introduce changes in the Orion, and it is not currently known when the drone will be fully accepted for service.

As well as the weapons, the Orion has two mission payload bays for other equipment, with a turret with electro-optical and infrared cameras, as well as a laser target designator to deliver guided weapons, being typically installed in the forward bay. Additional cameras or a surveillance radar can be mounted in the central bay. Other planned payloads include signal intelligence systems and electronic warfare jamming pod.

The full-service introduction of the definitive Orion will clearly be a big step forward for Russia’s military drone program and it will be the country’s largest operational UAV. The first frontline Russian operator is reportedly expected to be a UAV regiment of the Russian Navy, located at Severomorsk-1, part of the Northern Fleet, and which currently operates Forpost drones.

In Russian Navy service, drones are primarily used for coastal reconnaissance and target surveillance for warships and fighter jets. These missions don’t require the types of lightweight weapon systems that are now being tested on the Orion, suggesting that they may be intended primarily for the export market.

Kronshtadt, together with Russia’s Rosoboronexport arms export company, is already offering an export-configured Orion-E version to foreign customers. Despite being relatively new to the armed drone game, Moscow is now entering a booming sector, with the highly influential use of the Turkish TB2 attack drone in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, as well as in Libya. The TB2, which has ushered in a ‘game-changer’ level of attention on the modern battlefield, is in the same class as Orion. However, there is no direct competitor to the armed Orion or the TB2 from the United States, but China also offers a similar capability set.

Well-publicized problems reported with this class of Chinese-made drones in the hands of export operators could potentially offer a route to help Moscow secure very lucrative armed drone sales. Russia also has a far more extensive weapons export customer list to tap into than China or Turkey, especially when it comes to military aircraft. Competition from the United States is now primarily in the form of the MQ-9 that has been heavily pushed as of late, helped by relaxed export restrictions. The MQ-9, however, is a significantly more capable, and expensive, system. Additionally, those loosened U.S. export restrictions are still quite restrictive compared to the competition. Russia also has a track record of using creative financing to help sell military equipment to foreign customers, including low and very low-interest loans. They will also sell these systems to pretty much anyone.

On the domestic front, the demand for a UAV in the MALE class is also only likely to grow. Following the initial delivery of Orions to Russian Navy units, there is every reason to believe that they will fairly rapidly be issued to the Russian Aerospace Forces, too, who have learned about the potential advantages of armed drones from their experiences fighting in Syria. During that conflict, lower-end drones were used by Russia for surveillance, general target spotting, and bomb-damage assessments and were somewhat hampered by line-of-sight and/or low-bandwidth satellite communications restrictions. With this in mind, it will be interesting to see exactly what types of communications and connectivity options will be available for Orion once it emerges fully from development. Regardless, a more advanced and armed UAV would allow both the hunter and killer mission to exist on a single platform, simplifying operations and drastically expanding tactical possibilities, such as taking far greater advantage of targets of opportunity.

Exactly when we may see operational Orion UAVs carrying armament operationally is uncertain, but it will be equally fascinating to see whether this drone can make its mark on the burgeoning export market, as well as within the Russian military.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com and tyler@thedrive.com