The U.S. Navy is moving ahead with plans to expand its unmanned undersea vehicle capabilities with the acquisition of a new large-displacement design as part of its Snakehead program. The service wants these drones, which its nuclear-powered submarines will be able to launch and recover underwater, to initially be able to scout ahead or monitor certain areas, as well as perform other intelligence-gathering missions. It has plans to use them in other roles, including as electronic warfare platforms, in the future, as well.

Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) announced that it had issued the final request for proposals (RFP) for Snakehead’s Phase 2 on Dec. 23, 2020. The actual RFP is only available, at present, to companies bidding for the contract to build these large-displacement unmanned undersea vehicles (LDUUV). The Navy plans to pick a winning offer before the end of the current fiscal year, which ends on Sept. 30, 2021.

“Snakehead is a long-endurance, multi-mission UUV, deployed from submarine large open interfaces, with the capability to deploy reconfigurable payloads,” an official Navy press release regarding the RFP said. “It is the largest UUV intended for hosting and deployment from submarines.”

“Initial vehicles will be designed to support Intelligence Preparation of the Operating Environment (IPOE) missions,” it continued. “Future vehicle missions may include deployment of various payloads.”

IPOE, in layman’s terms, is a mission set that involves collecting information about a particular area or objective ahead of an operation, to help with planning. UUVs used in this role typically have a mixture of sensors, including side-scan sonars and bathymetric sensors, to create detailed maps of the seabed and otherwise identify potential hazards or other objects of interest.

The video below shows the kind of imagery that be produced using side-scan sonar.

For submarines, this information is critical for being able to safely ingress and egress from a designated area, especially a denied or otherwise sensitive one, safely and with the lowest chance of detection. If the objective itself is underwater, such as a sunken object or undersea cable, a Snakehead could also help confirm its general location and the presence of any hostile forces in the area, all without its host boat having to perform this kind of reconnaissance directly, which could put it at increased risk.

What obstacles might exist under waves would be valuable details to pass along to teams of special operators, which the submarine in question might be carrying itself, as they prepare to carry out various missions. This could include raids, either in the water, such as blowing up ships in a port using munitions such as limpet mines, or ashore. An IPOE mission could also be in support of a larger-scale amphibious operation.

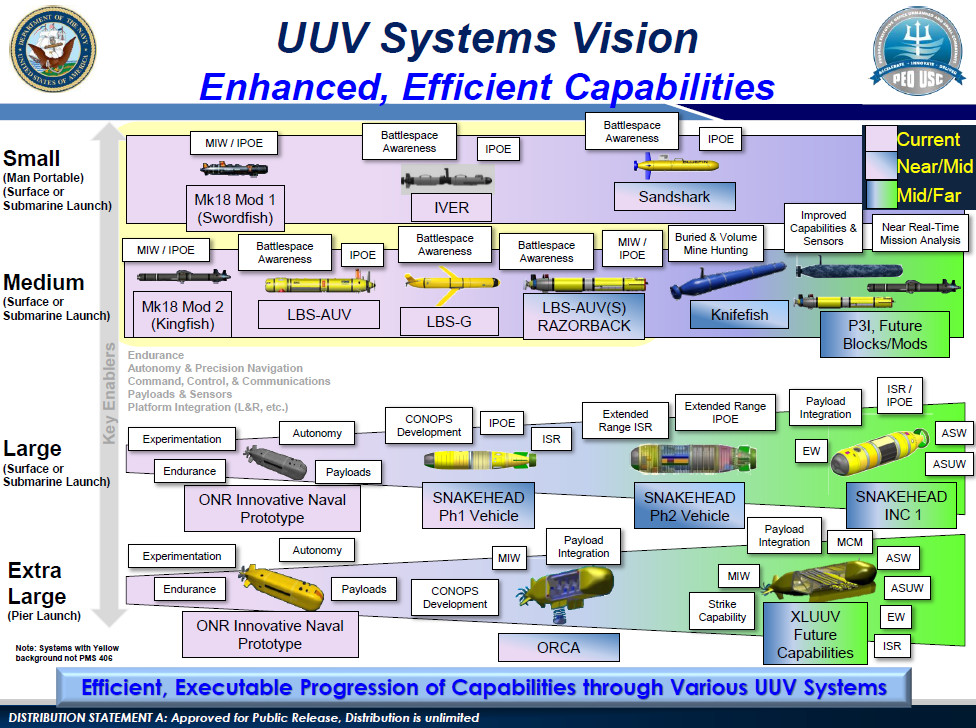

The Navy has said in the past that Snakehead should be able to carry out more general intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) missions, as well. IPOE and general ISR were the mission sets that the service said it planned to explore using the initial Phase 1 Snakehead design, which it previously expected to have in the water by 2019. At the time of writing, the first Phase 1 Snakehead is still under construction and is not expected to be delivered until sometime next year.

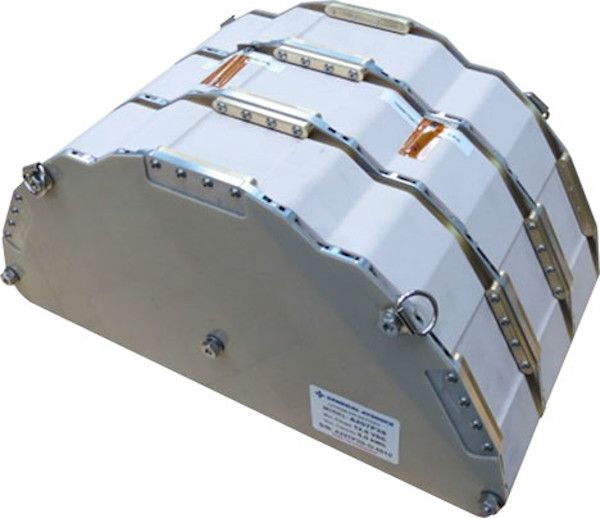

Details about this initial Snakehead UUV are extremely limited and it is unclear what companies exactly are involved in building it. In 2019, Advanced Technology International did announce that it had awarded a contract to General Atomics Electromagnetic Systems to develop a Lithium-ion Fault Tolerant (LiFT) battery for the Phase 1 Snakehead. The goal was for the LiFT battery to provide improved safety and reliability, while also offering sufficient power to support longer-endurance missions.

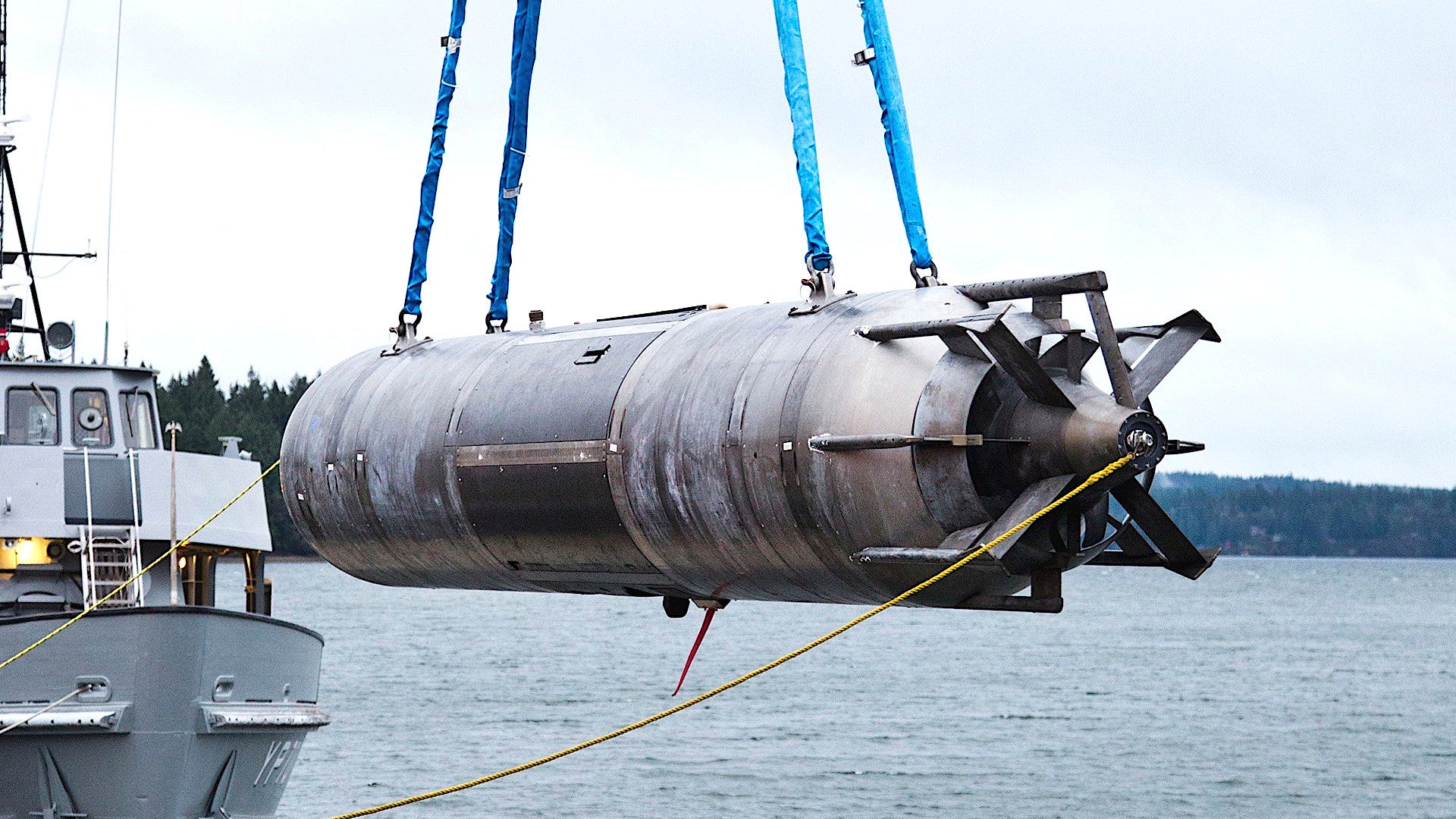

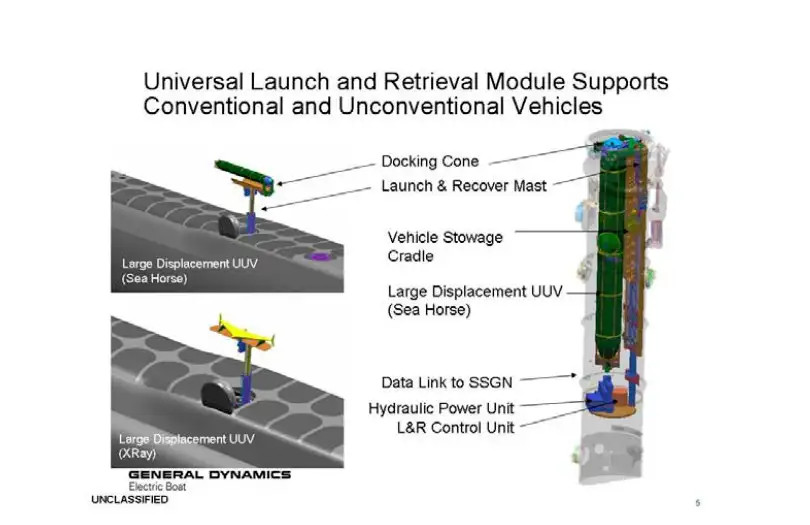

In the meantime, the Navy’s Unmanned Undersea Vehicles Squadron One (UUVRON-1), the service’s first dedicated underwater drone squadron, which it activated in 2017, has been using two earlier LDUUVs that the service previously acquired from the Applied Research Laboratory (ARL) at Pennsylvania State University. The first these was the 28-and-a-half-foot-long, 10,800-pound Sea Horse, the development of which began in 1999 and that you can read more about in this past War Zone piece. The more recent Sea Stalker, also known as Large Training Vehicle 38, is a derivative of the Sea Horse design.

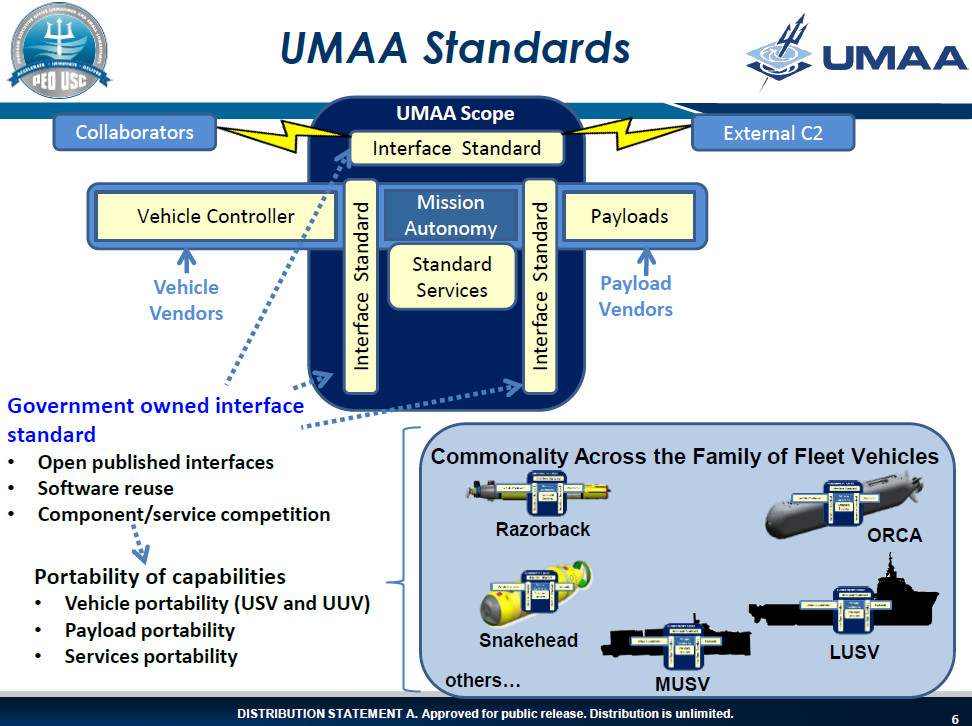

Without being able to see the full RFP, we don’t know what the Navy wants in terms of general performance, endurance, or other capabilities from the Phase 2 Snakehead design. The official contracting notice does say that the service expects these new drones to have some ability to operate with at some autonomy, using the Unmanned Maritime Autonomy Architecture (UMAA) and the Common Control System (CCS).

UMAA is a common set of systems and software that the Navy has been working on to support work on increased autonomous functionality for UUVs, as well as unmanned surface vessels (USV). CCS provides a common tool for UUV and USV mission planning and execution, as well as monitoring the systems on those vehicles during operations.

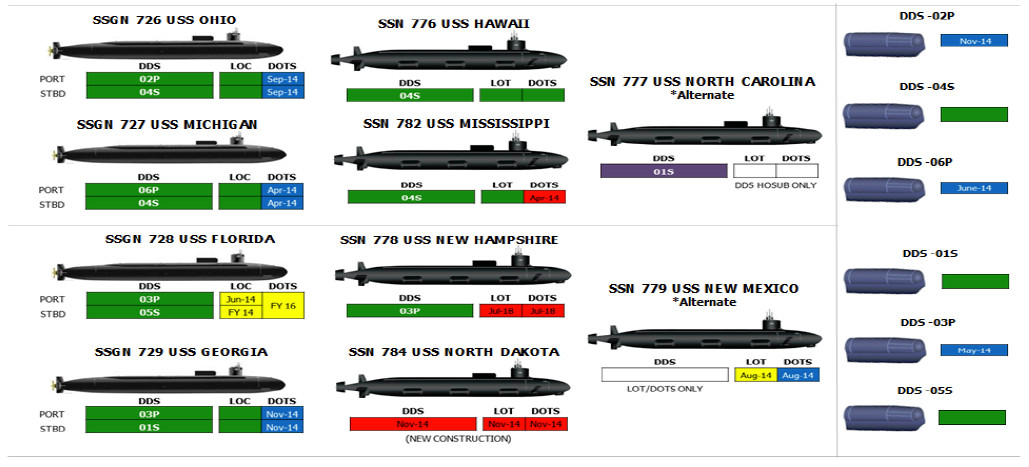

It’s also not clear what submarines might be slated to employ Snakeheads in the future. The Navy has said that “the LDUUV will achieve full integration with Modernized Dry Deck Shelter and Payload Handling System-equipped submarines.”

The Navy presently can fit Dry Deck Shelters (DDS) onto its four Ohio class guided-missile submarines, or SSGNs, each of which can carry two at a time. At least six more Virginia class attack submarines are configured to carry a DDS, but there are not enough of the shelters to equip all of those boats at once. The Seawolf class spy submarine submarine USS Jimmy Carter, which is a unique subclass unto itself, has an 100-foot-long Multi-Mission Platform (MMP) section of its hull that also has a large “ocean interface” that could be used to launch UUVs.

The DDSs allow for the deployment of large payloads, such as miniature submarines that special operations forces use to get to shore undetected, like the existing Mk 8 SEAL Delivery Vehicle (SDV) and the future Mk 11 Shallow Water Combat Submersible (SWCS) and Dry Combat Submersible (DCS). They also provide a way for large numbers of special operators to deploy from a submerged submarine all at once.

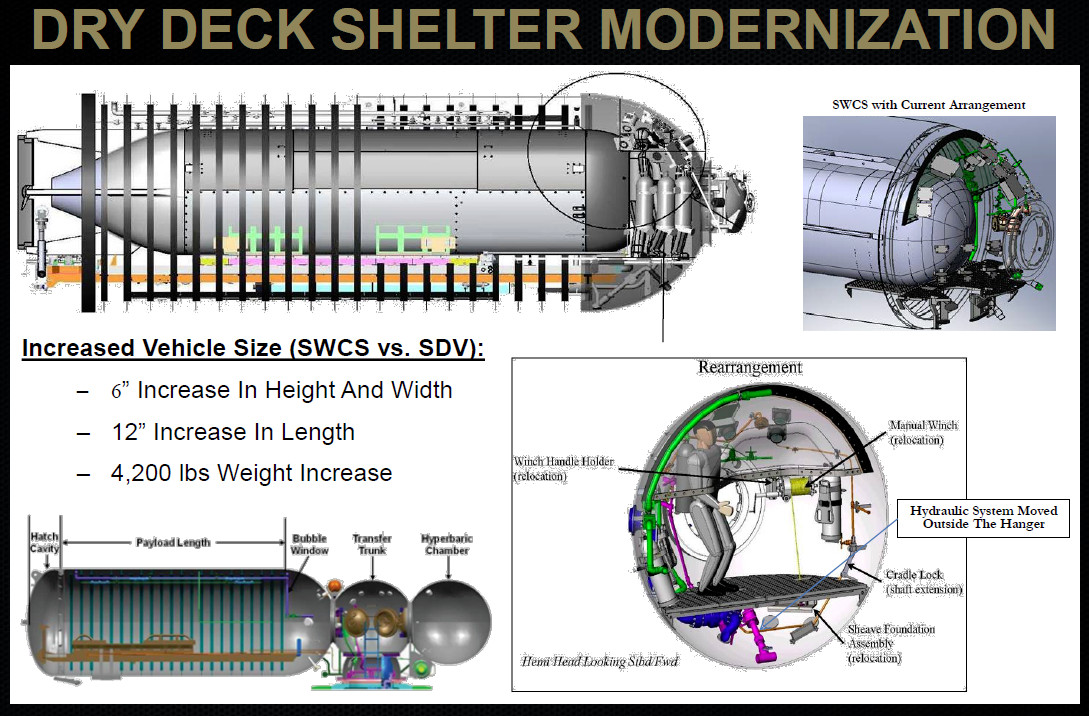

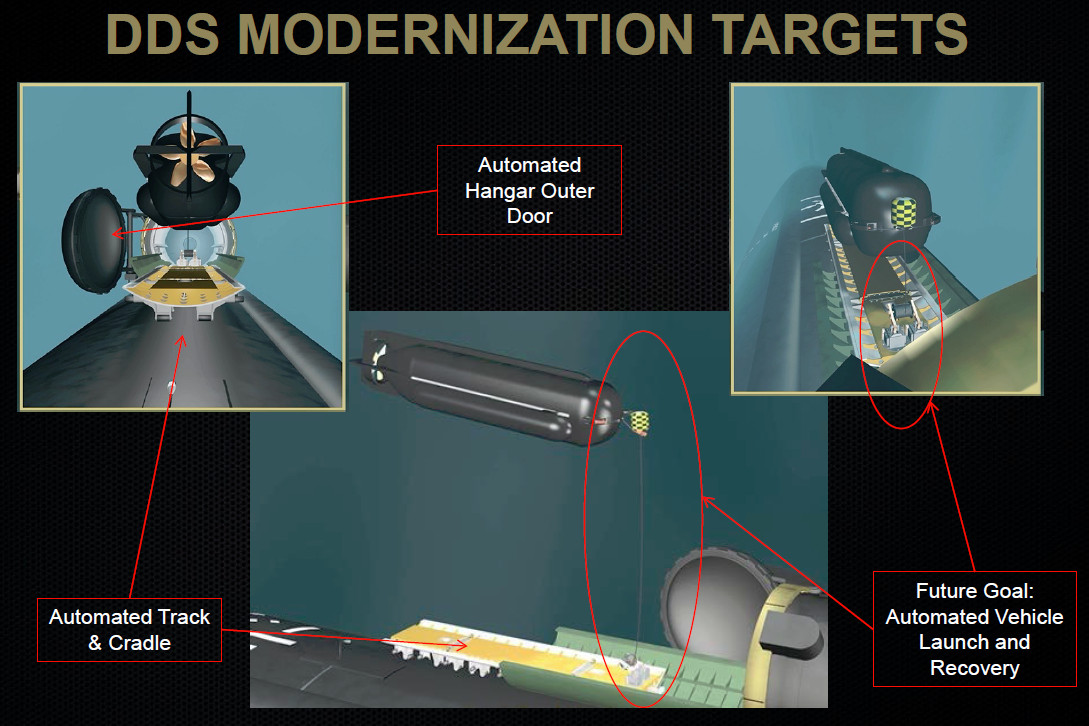

Work to modernize the existing DDS design has been focused on increased the overall volume inside the shelter to accommodate larger payloads, as well as the integration of an improved payload handling system to enable it to launch and recovery large, semi-autonomous or fully-autonomous UUVs.

It’s worth noting that the Navy has explored other kinds of payload handling systems for deploying LDUUVs, such as Sea Horse, as well as other kinds of drones, from the missile tubes on the Ohio class SSGNs, versions of which are likely in service now. You can read more about these developments in this past War Zone feature. The service has also launched Sea Stalker on the surface from an Arleigh Burke class destroyer on at least one occasion.

The Navy also envisions the Phase 1 and 2 Snakeheads as leading to a more robust Increment 1 type that might also support anti-surface and anti-submarine warfare activities, such as helping in the hunt for enemy ships and submarines. This would give submarines something very loosely similar to the “loyal wingman” type drones that the U.S. Air Force, among others, is developing to work together with manned combat jets.

They could also provide the aforementioned electronic warfare capability. An electronic warfare payload would require the UUV to run on the surface, or at least close enough to extend some kind of mast above the waterline. Still, an LDUUV carrying out this mission would be a much lower-risk alternative to doing it with a traditional crewed submarine. A Snakehead could also be employed in a similar fashion equipped with an electronic support measures (ESM) system to grab information enemy emitters, such as radars and communications nodes, to help build a so-called “electronic order of battle” of hostile fleets at sea or facilities along the shoreline. The same could be said for intercepting certain communications.

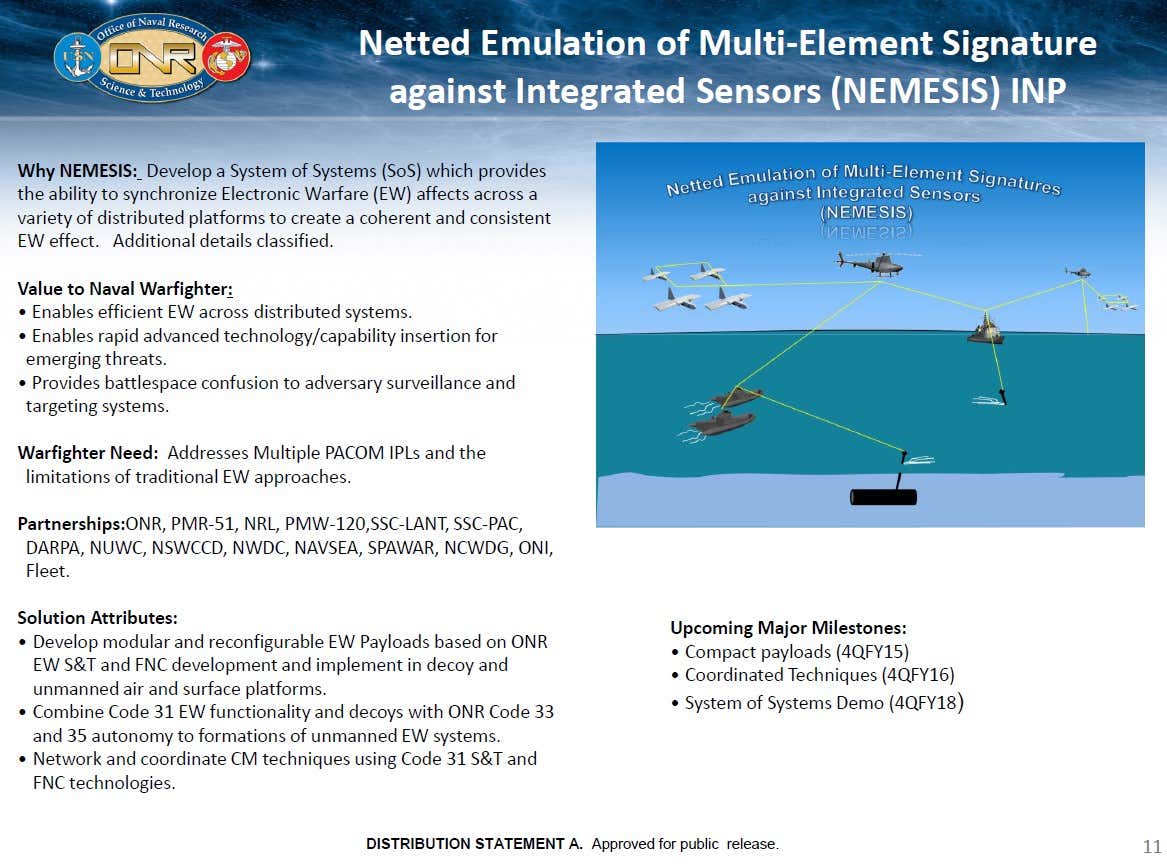

In a similar fashion, Snakeheads could be employed as a component of the Navy’s shadowy, networked electronic warfare “ecosystem,” known as the Netted Emulation of Multi-Element Signature against Integrated Sensors, or NEMESIS. This program has been working to develop a ‘system of systems’ to work together across a battlespace via linking electronic warfare-enabled manned and unmanned aircraft, ships, and submarines. Combined, they could effectively create highly convincing phantom fleets to distract and confuse opponents, as well as employ other highly impactful electronic warfare tactics in a cooperative manner. Unmanned underwater vehicles are clearly a component of this program based on its own illustrations. You can read more about this project in detail in this past War Zone feature.

The Snakeheads will all be modular, open-architecture designs to allow for the relatively rapid integration of new payloads and other functionality as time goes on. These underwater drones look set to significantly expand the ISR capabilities of various submarines, especially the Ohio SSGNs, which are already very capable in this regard and are in high demand as a result, as well as future submarines the Navy is eyeing to specifically carry and deploy larger payloads. The service has also historically had a small number of special mission submarines available for espionage and other more specialized intelligence-gathering missions, such as the aforementioned USS Jimmy Carter, any future examples of which could also make good use of this kind of unmanned underwater capability.

The Snakehead program represents just one tier of the Navy’s overall UUV plans, which also include small and medium tiers of underwater drones, as well as an extra-large category. Last year, Boeing won the contract to build the service’s first four XLUUVs, also known as Orcas, which you can read about in more detail in this previous War Zone story.

In general, the Navy sees unmanned platforms that operate below and above the waves as increasingly critical to its future operations, especially in support of distributed warfare concepts of operation that will require its forces to conduct a wide array of missions across broad areas simultaneously. Together with the service’s expanding communications and data-sharing networks, as well as those in development elsewhere across the U.S. military, growing fleets of UUVs and USVs are set to offer important additional operational capacity across multiple mission sets with more limited personnel, infrastructure, and logistical demands.

Above all else, Snakehead will give America’s already incredibly capable fast attack and guided-missile submarine fleet a whole new capability set that will drastically expand the tactical playbook available to them. One can see where this is headed in the future, and given the limited number and already overtasked nature of the U.S. Navy’s submarine fleet, Snakehead could allow an SSN or SSGN to be in two places at once, at least to some degree. Overall, this capability is a huge step in moving more deeply into the unmanned space when it comes to the shadowy world of undersea warfare.

Next year could be a particularly important one for the Snakehead program with the Phase 1 design set to finally hit the water and the service now also planning to get work started on the improved Phase 2 type.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com