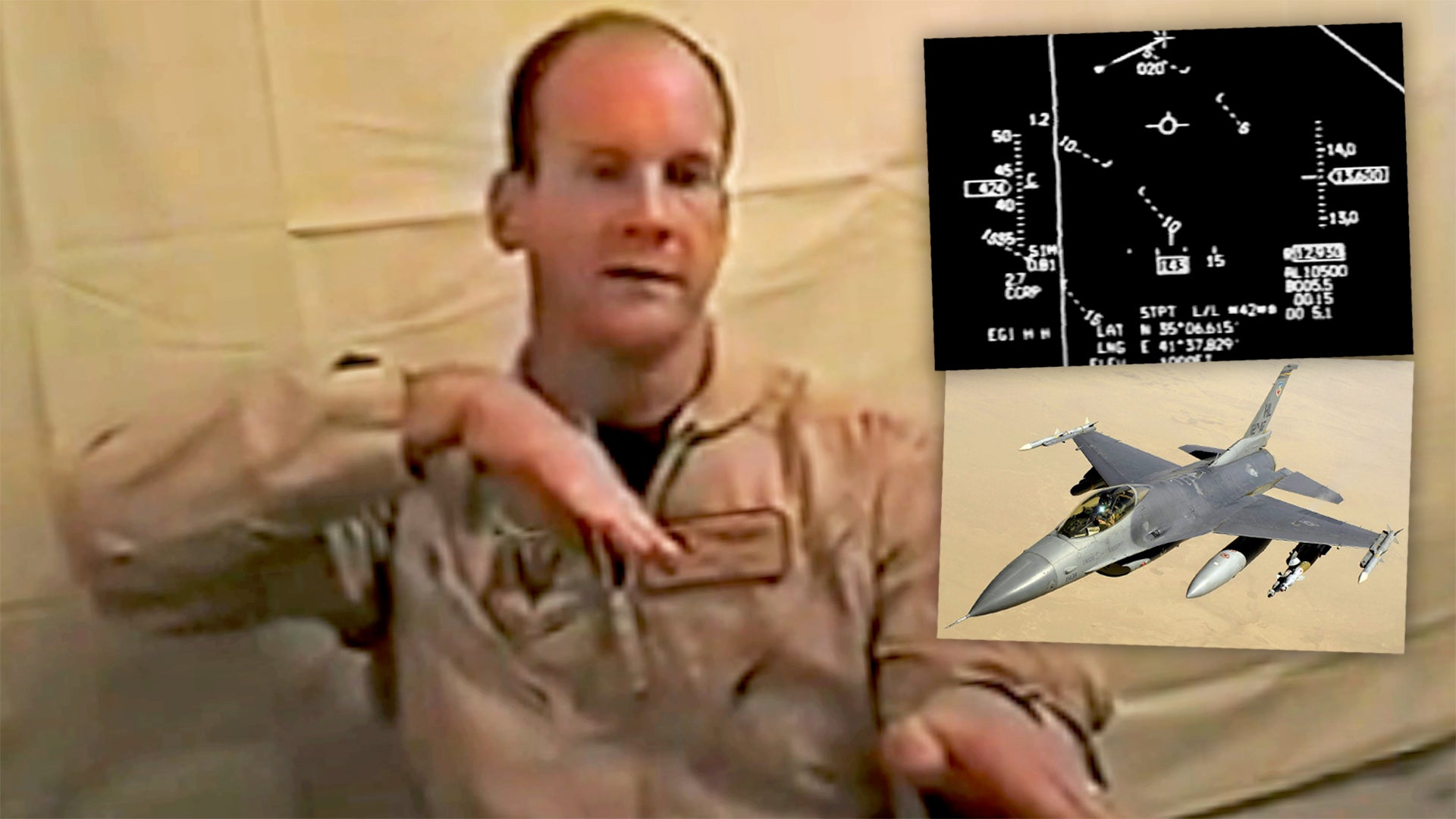

Edward “Ned” Linch III, then a U.S. Air Force Major, was flying his F-16 fighter jet over western Iraq on the night of March 30, 2003, when he and his wingman were diverted to support troops that were in desperate need of air cover. What unfolded was, in Linch’s words, “the most intense mission I’d ever flown in my life.” Thanks to a video interview, you can hear him talk all about the mission that saw him thankful for escaping alive, and later led to him receiving the Distinguished Flying Cross. The film also includes some intense audio and HUD camera sequences from the flight itself.

First, a little background. Edward Linch III, now retired, joined the Air Force in 1986 and undertook training on the F-111 strike aircraft at Mountain Home Air Force Base, Idaho, followed by an operational posting to RAF Upper Heyford, England.

After attending Euro-NATO Joint Jet Pilot Training (ENJJPT) at Sheppard Air Force Base, Texas in 1989, he converted to the F-16 at MacDill Air Force Base, Florida, and began a 12-year operational career in the Viper, including more than 2,0000 flying hours that took him on tours at different stateside bases and Kunsan Air Base, Korea. In the wake of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, he flew F-16 combat air patrols during Operation Noble Eagle.

Linch also flew more than 150 combat hours in his career, including Operations Northern and Southern Watch over Iraq, and Iraqi Freedom. It was a mission during the latter campaign — when he was deployed with the Alabama Air National Guard’s 160th Expeditionary Fighter Squadron — that he describes in the video.

The night in question, then-Major Linch was flying as “Honcho 23,” alongside his wingman, Captain Brian Wolf. Their planned mission involved hunting down Iraqi Scud ballistic missiles in western Iraq.

It was a grueling mission already, six hours long, but was heading toward its end when the call for support came in. The pilots then diverted to an area 400 miles inside enemy territory where the troops needed assistance. In another video about the mission posted to the same account, the location is described as “North of Al Qiam [sic] and just east of Syria.” This likely implies somewhere near Al-Qa’im, an Iraqi town located around 250 miles northwest of Baghdad, near the Syrian border.

Before long, the seriousness of the situation became clear, as frantic radio calls came in on the guard radio frequency, which was reserved for emergencies.

“One guy was going hysterical,” reflected Linch subsequently. “These were the most desperate and urgent radio calls I’ve ever heard. The calls were difficult to understand at times since they were in such dire straits under fire.”

Watch Linch’s entire account of the events on that day and hear the frantic radio calls from the troops he was trying to protect in the video below:

The soldiers in question were Coalition special operations forces surrounded by hostile Iraqi forces that outnumbered them by around 20 to one. The enemy soldiers were only around 300 yards from the Coalition forces and closing in fast. In the other video, it is noted that the Coalition soldiers were from the elite British Special Boat Service, and at least one of the accents heard does seem to be British.

As the voices on the guard frequency became ever more frantic, Linch and Wolf pushed their jets to the limits to get on scene as quickly as possible.

“We disregarded concern for ourselves and pressed beyond the limits of our jets, its equipment, and our personal limitations,” Linch said later.

Now that they were well away from the scene of their previous Scud-hunting mission, the pilots had little idea about the environment below them. They lacked information on the local terrain, lines of communication, and potential threats in the area.

Although they were kitted out with night-vision goggles, or NVGs, a huge sandstorm the day before meant there was hardly enough illumination for them to actually work properly, as Linch explains in the video. In fact, it needed a combination of NVGs, the onboard radar, and the Situational Awareness Data Link, or SADL, for the two F-16s to just keep tabs on each other.

“Despite the extreme risk to himself and his flight, [Major Linch] descended through the hazardous conditions to provide immediate air support for the trapped team,” an Air Combat Command press release explained.

“We had to act now or these guys were going to die,” said Linch. “I knew we were their only hope at the time to survive; I was going to try to help them regardless of the conditions or the safety of my flight.”

With only an intermittent infrared strobe from the ground troops visible to orientate them, Linch pressed on and led several reconnaissance passes and bomb runs over the position. In the process, he also directed his wingman to drop a single 500-pound bomb.

In some troops-in-contact scenarios, that might have been enough, but not in this case. The enemy troops kept pressing on toward the Coalition special operations elements, leading Linch to reassess the situation. Concerned that dropping more bombs could result in friendly casualties, Linch decided instead to make low-level “show-of-force” passes over the area, with the aim of deterring the enemy. All this, of course, with seriously compromised situational awareness.

Linch reckoned it was “one of the worst weather situations I’ve ever flown in,” said Linch. “With poor visibility due to the dust and haze, it is difficult to differentiate the ground from the clouds — you’re basically flying around in a milk bowl. The NVG picture looks like snow on a TV; it’s just all shades of green.”

“With no moon and stars to provide illumination for my NVGs and no horizon to reference, it was almost impossible to visually fly the aircraft without referencing the instruments but I had many of my cockpit lights turned off and a few set to a very dim setting in order to assist me in finding their IR strobe. I had to rely on my wingman to call out critical information such as my altitude.”

As well as the low-level passes, the two F-16 pilots started punching out infrared decoy flares from their jets, as another distraction to the enemy below. This, however, made their own position even more obvious to the Iraqis, while further reducing the effectiveness of their NVGs.

Incredibly, the two pilots continued this effort for another half an hour, all the time with the risk of spatial disorientation, in almost zero visibility, and frequently dropping below the safe altitude limits.

“Eventually, the Coalition forces were able to break through the line of enemy troops and proceed to a safer position,” the Air Combat Command report concluded.

Linch attributed the combination of the bomb, flares, and the noise as having allowed the friendly troops to escape and, the following day, all were rescued.

After receiving his Distinguished Flying Cross for heroism, Linch said: “I give a lot of credit to my wingman, Captain Wolf, for his efforts that night, and to God for protecting everyone in a situation that could have claimed many lives.”

Editor’s note: A big thanks to Jack Lobo for the heads up on this video.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com