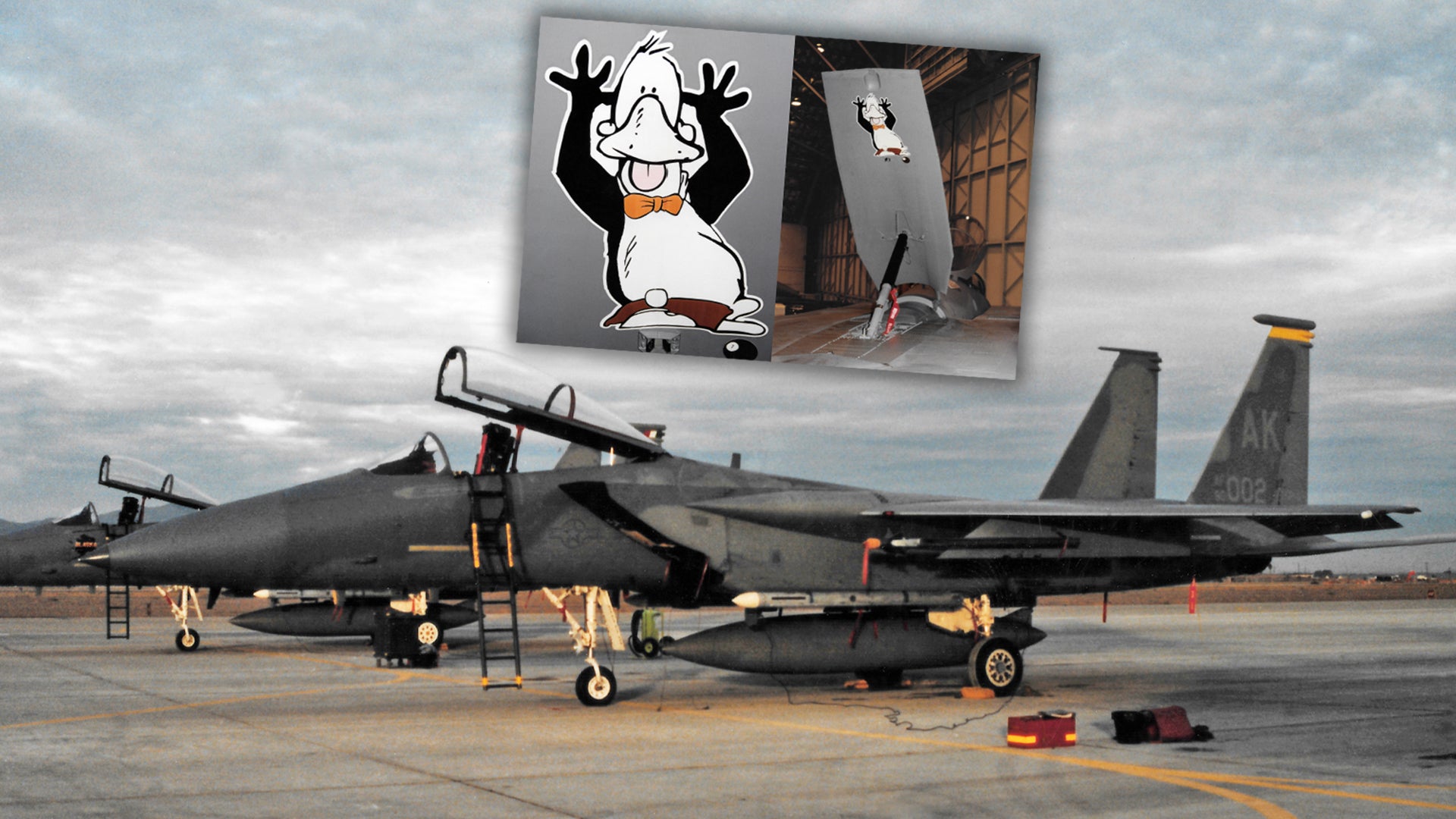

Every fighter jet ever made comes with its own unique quirks and personality. The pilots that fly and airmen that maintain these aircraft know this all too well. But occasionally an aircraft will roll off the production line destined for unique notoriety and will continue to stand out from the rest—for better or worse. Enter F-15C tail number 80-0002—or just 0002 in USAF parlance—nicknamed “Opus.”

Unlike ships of the Navy that generally enjoy a well-documented and public-facing service career, jets in the Air Force are much harder to keep track of. It makes it difficult as airmen move on from their tours of duty to keep up with their favorite aircraft. As a result, much of the history of Opus is shrouded in the folklore that comes from countless retellings of its stories and the verbal “you just had to be there” history surrounding it.

I like to imagine that Opus rolled off the McDonnell Douglas production line in 1980 looking like Stephen King’s Christine: painted bright red and ready to rock. While the truth is much more pedestrian, it wouldn’t have been surprising given what the future would hold.

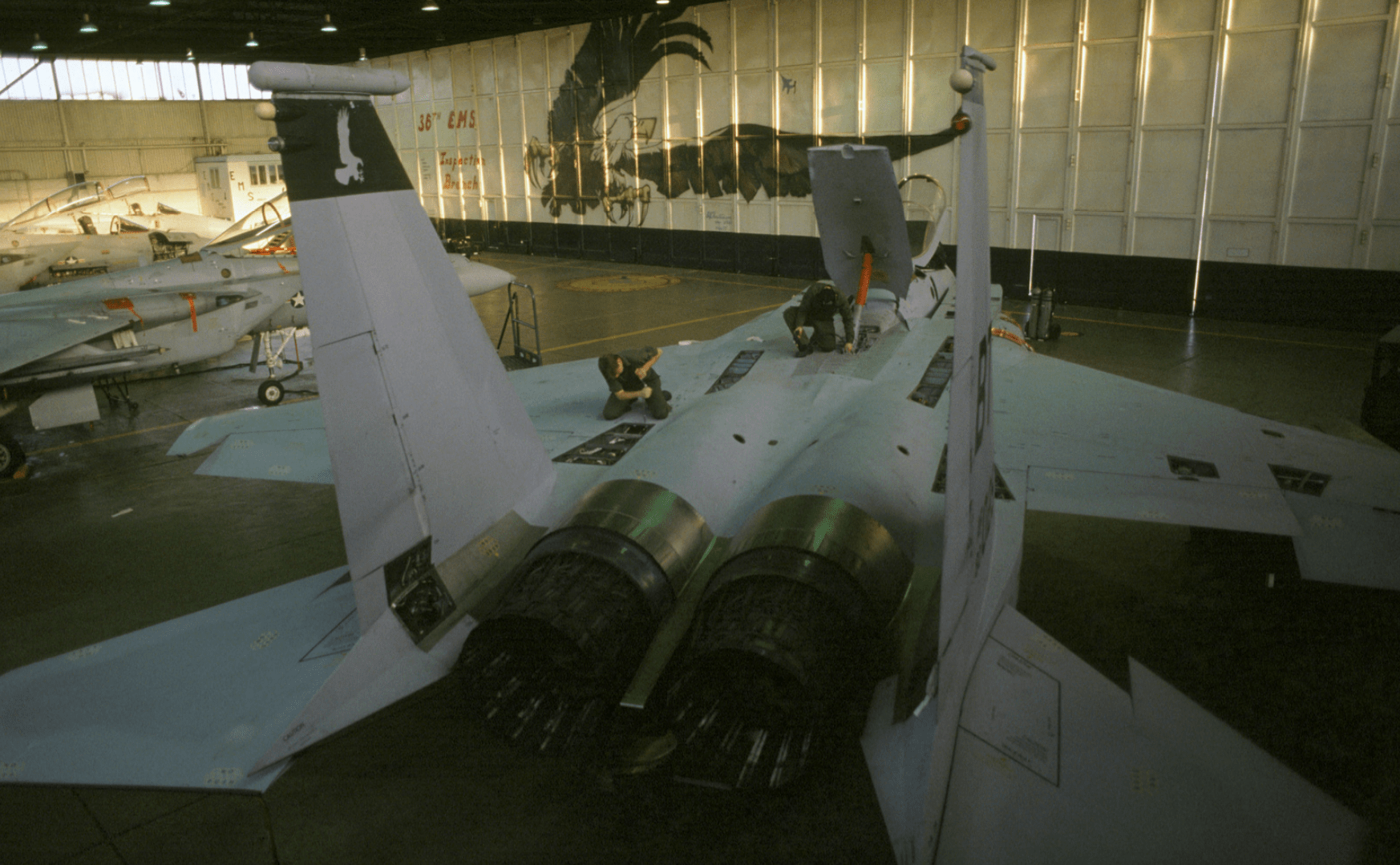

During this time, the 36th Tactical Fighter Wing, later renamed the 36th Fighter Wing, stationed at Bitburg Air Base in Germany, began receiving F-15C/D models to replace their A/B models. Opus and many of her sisters were ferried over to Europe and distributed amongst the wing’s three resident fighter squadrons, the 525th, 22nd, and 53rd. They were immediately put to work for U.S. Air Forces in Europe (USAFE), but Opus was already primed to stand out.

The story goes that while being towed back to the hangar, the towbar broke and Opus rolled down a graded pathway and collided with a building. There does not seem to be a record of this incident on file anywhere. It was not found on the Class A/B/C Mishap reports from the era, but that may be due to the incident occurring over 35 years ago. What is known is that the brand new F-15 spent more than a year up on jack stands while the Air Force decided whether it was worth the investment to repair her.

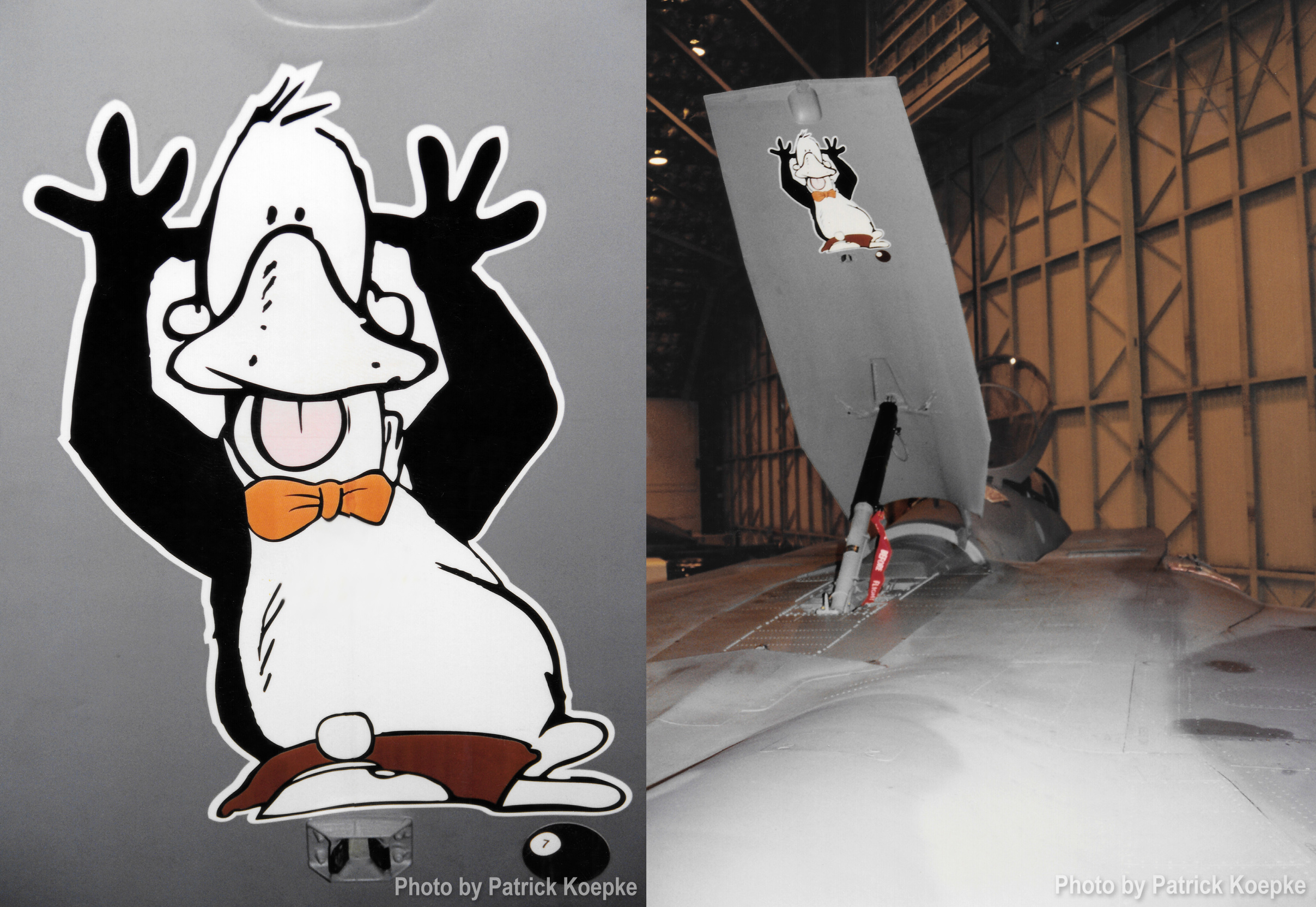

This is where the nickname Opus originated. The jet was named after the penguin in the Bloom County comic strip. This must have seemed fitting since a penguin is a bird that can’t fly.

Eventually, the decision was made to get Opus airworthy again, which leads us to Elmendorf Air Force Base.

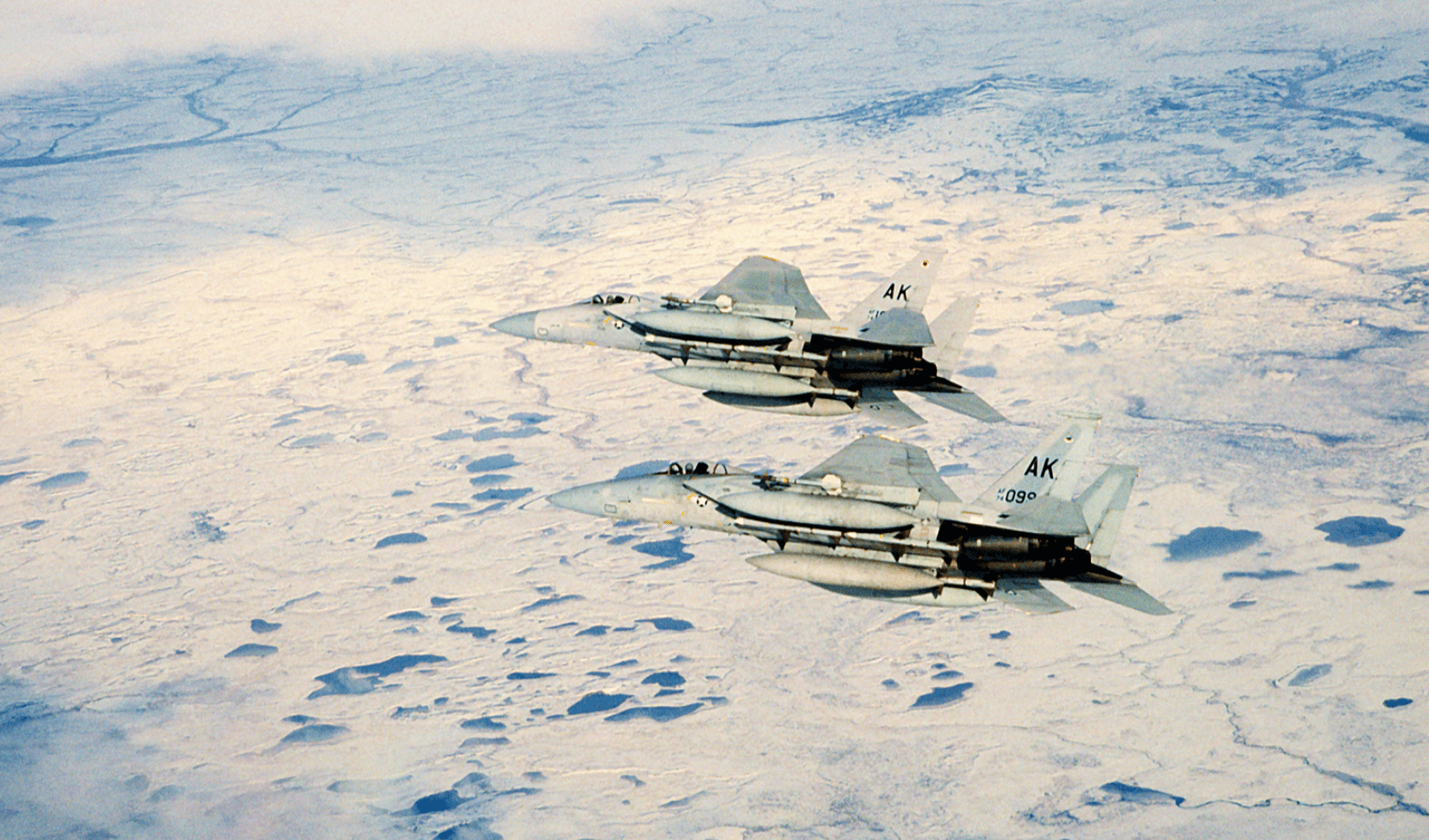

By May of 1987, Bitburg was in the process of reshuffling its stable of Eagles and some of its aircraft were being moved to squadrons located at other bases around the globe. A number of these jets went to Spangdahlem Air Base in Germany and Elmendorf Air Force Base in Anchorage, Alaska. Opus was assigned to the latter, joining the 54th Tactical Fighter Squadron of World War II fame.

The next big incident with Opus made the national news and marked a dubious first for an F-15. On March 19th, 1990, a two-ship flight including the squadron commander, Lieutenant Colonel Harris, flying 1054, and Lieutenant Lynch flying Opus, took off for “the sites”—small forward operating bases in Western Alaska. A number of circumstances coincided where a live AIM-9M Sidewinder air-to-air missile sat on Opus’s right pylon (station 8 A or B), while a captive training AIM-9 had been loaded on the left side. It wasn’t out of the ordinary at the time to ferry a live missile to King Salmon or Galena.

The pilots spent a portion of the mission dogfighting and when Lynch got a tone from the sidewinder signifying it had locked onto Harris’s jet, he hit the pickle button to simulate firing the missile. Suddenly, the live AIM-9 jumped off the launcher and raced towards 1054. Lieutenant Colonel Harris was able to break and evade, but the missile still shredded the tail of his F-15 and damaged its engine. And so Opus became the first F-15 to have hit another F-15 with live ordnance.

Both jets were able to return to base and the incident brought several changes to the T.O.s (Technical Orders) at the time. An emphasis on visual indicators on the missiles was also mandated, to differentiate “CAP 9s” from live missiles. 1054 was repaired and continued to serve as the ‘squadron jet.’

Like many airmen whose careers take them to the flightline, I experienced some minor hazing when I first arrived. While on the flightline learning how to pull my first pylon, I was sent in to tell Support (the tool room) that we needed prop wash. I could hear the laughter all the way across Hangar 1’s expanse as I made my way back out to the flightline.

But my experience pales in comparison to another airman whose tour of duty with the 54th Fighter Squadron preceded mine. As the story goes, he was told to report to Opus, which was going to be doing an engine run up test. He was instructed to don the “wash rack” gear, which included full-length waterproof coveralls, safety goggles, and thick gloves—gear usually meant to be worn while washing the aircraft. Waiting for the airman was a small six-foot ladder set up about five feet behind Opus’s jet engine exhaust nozzles.

Following instructions, this airman climbed to the top of the ladder, facing the business end of Opus, under the pretense of “measuring the thrust.” Had he actually attempted it, he would have been blown several hundred feet down the flightline.

They say he stood up there on the ladder like a statue, even as the JFS (Jet Fuel Starter that spools up Engine 1) began to howl. The crew that was in on the joke had to shut down the JSF before the airman got hurt.

He was either incredibly naive or was willing to risk life and limb to call their bluff.

Opus notched another first in 1995, while the 54th Fighter Squadron (now under 3rd Wing’s command) was on a detachment to Luke Air Force Base outside of Phoenix, Arizona. Typically the Air Force ground crews you see on a flightline are made up of three primary maintenance flights within the squadron: Crew Chiefs who maintain, launch, and recover the aircraft, Weapons Troops who load ordnance and assist with launch and recovery, and Avionics Technicians who deal with the aircraft’s electronic systems.

The entire launch process was a choreography of motion and coordination that was a sight to behold. The Crew Chief was the A-Man, a role that inspected the aircraft (usually before and with the pilot), helped the pilot buckle in, walked through the pre-launch checklist with the pilot, and confirmed flight surface checks were nominal. From there, the A-Man stood in front of the jet ready to marshal the aircraft out of its parking spot.

The Weapons Troops owned the B-Man’s job, which was to pull safety pins and kick the chocks on launch, and be ready with the halon bottle should a fire occur. This makes sense because many of the safety pins are inserted into the Eagle’s weapons systems.

I always wanted the A-Man role. I didn’t mind kicking chocks, but was envious of the Crew Chiefs. I somehow convinced my Flight Chief to let me get A-Man qualified, and spent some time prior to the trip to Luke training with Opus’s DCC (Dedicated Crew Chief).

One early morning at Luke, the Quality Assurance team watched me launch Opus and declared me A-Man qualified. I remember being pretty nervous, especially during the flight control check, and remember telling the pilot “good hunting” as I disconnected the cable and moved to the front of the jet. To my knowledge, I was the first Weapons Troop member that got A-Man qualified from Elmendorf and it was fitting that Opus was the one being launched.

Opus was a different kind of aircraft. The life of a Crew Chief is such that you stayed on a broken aircraft until it was fixed. That meant many late nights under the hangar lights with every engine panel opened and every tool and diagnostic tool utilized. I remember Opus’s DCC often staying behind trying to chase an elusive “red X” (a serious problem impacting flying status) while nearly everyone else ended their shift and went home. As a Weapons Troop, I didn’t take part in this recurring “tradition,” other than occasionally helping pull panels on the aircraft when time permitted.

We all had our nicknames for planes that were troublesome. “Pig.” “Hog.” “Hangar Queen.” One jet was broken down so long in Hangar 1 that someone taped a picture of an ear of corn to the nose cone. In Opus’s case, she was never out of commission long, but no repair was easy and no solution clear cut. Her reputation was as a high-visibility melodrama at all times.

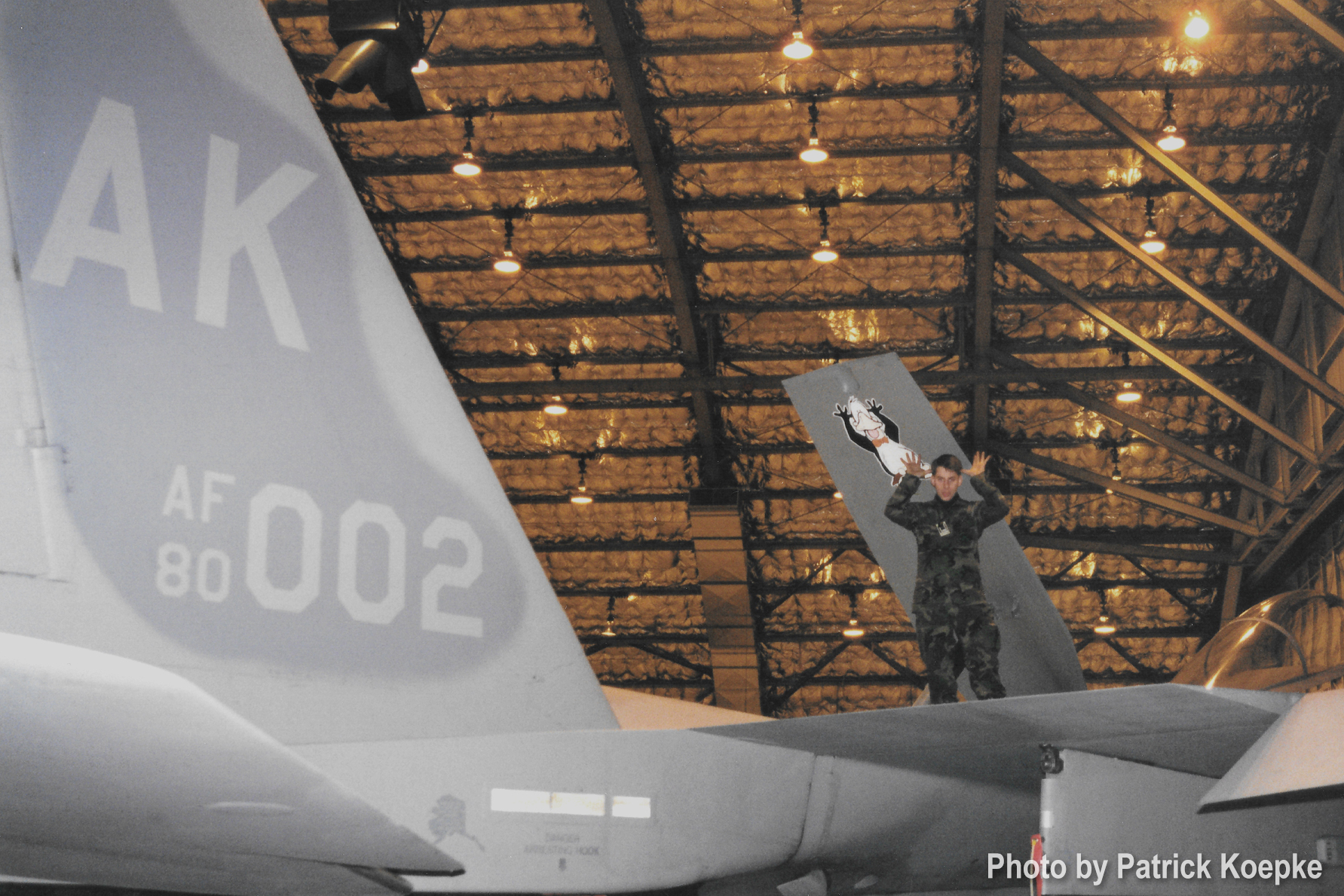

The next “first” involved a nose art initiative, this time in 1996. In talking with Opus’s DCC, we cooked up an idea to paint the Bloom County penguin character on Opus. At the time the Air Force was pretty strict regarding nose art and/or individualizing the aircraft, though they have lightened up a bit since then. As a result, we had the idea to conceal the artwork on the underside of the air brake, which is a huge panel that extends from the upper fuselage of the jet when the pilot wants to slow down fast. So, it wouldn’t be visible under normal circumstances.

I wrote a proposal to the 3rd Wing’s Commander explaining how nose art fostered squadron unity and identity, and helped both the pilots and maintenance troops feel pride in their aircraft. I was expecting it to be rejected, but it was not only approved, but it was given the ‘wing king’s’ full support. This meant we could involve the Paint Shop—the hangar and airmen that paint the jets—in our ideas and they would make it happen. They helped make vinyl-like images that were applied with soap and water and were designed so they could withstand the weather.

It made sense for Opus to carry the first artwork, which ended up being the character Opus with thumbs in its ears and its tongue sticking out. It was a way to “give the bird” to your opponent in a dogfight.

Other jets in the wing started being seen taxiing to EOR with artwork on the backside of their air brakes, and it was fun to see what others were coming up with.

I don’t know how long the artwork stayed on the jets at Elmendorf. I out-processed near the end of 1997, but they were there when I left.

A few years after I left Alaska I heard the older F-15C/D aircraft (built between ‘78-82) were replaced with newer models (I believe ‘84-87). This sent Opus to Nellis Air Force Base, where she joined the 65th Aggressor Squadron.

When the 65th was inactivated in 2014, Opus landed with the 159th Fighter Wing, flying for the 122nd Fighter Squadron. As of the time of writing this story, Opus is still flying high down in Belle Chasse for the Louisiana Air National Guard.

In talking to a few maintenance members from the 159th, Opus took part in the F-15 Persistent Air Dominance Enabler test, which meant she was fitted with Conformal Fuel Tanks and used in the Boeing program. It is safe to say any maintenance issues Opus may have had up in Alaska seem to have cleared up. One crew chief called Opus a “code 1 machine”—code 1 meaning an aircraft with no broken systems and is fully mission capable before a flight.

No doubt the pilots and maintenance troops in Louisiana have their own Opus stories to tell.

No one person can claim sole ownership over the rich folklore surrounding Opus. This article only scratches the surface. It’s a safe bet nearly every pilot and maintenance crew that worked around 0002 has their own stories.

One thing is certain, out of the 1,500 F-15s built over the years, Opus truly is one of a kind, and belongs to every pilot that has flown her and airman that have maintained her.

Patrick Koepke served as a 462/2W1 “Load Toad” in the mid-’90s with the 54th FS “Fighting Leopards” at Elmendorf AFB, Alaska. Now he lives in central Texas where he is a writer and occasional songwriter.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com