In its latest 30-year shipbuilding plan, the Navy is looking to halt its purchases of future Ford class aircraft carriers and begin development of a new type of flattop, step up the acquisition of new Constellation class frigates, and acquire more unmanned surface and underwater vessels, among other things. Criticism has already been leveled at the proposal, which would see a major Navy budget increase fueled, in part, by cuts to the Army and the Air Force.

On Dec. 10, 2020, the White House’s Office of Management and Budget released a Fiscal Planning Framework (FPF) to go along with the Navy’s newest 30-years shipbuilding plan, a public version of which has not been made available at the time of writing. The Wall Street Journal also published an accompanying op-ed from OMB head Russell Vought and President Donald Trump’s National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien, titled “The Navy Stops Taking On Water.”

“The seminal document is the result of an unprecedented nine-month study of naval force structure by the Pentagon,” Vought and O’Brien wrote. “It provides a detailed blueprint to lawmakers and industry partners, reinforcing the American commitment to maintaining maritime supremacy.”

The key elements of the 30-year shipbuilding plan as found in the FPF are seen below.

Far and away the most notable item is the plan to stop buying any more Ford class aircraft carriers – four are under construction or on order now – and begin crafting a new type of carrier. The FPF does not say what kind of carrier the Navy would be looking to develop, but the service has indicated an interest in acquiring new light aircraft carriers as part of its most recent force structure proposal, known as Battle Force 2045.

It’s interesting to note that, in March, there were reports that the Navy was considering only buying four Ford class aircraft carriers and then pursuing a new class of light aircraft carriers. In May, the service had said it had indefinitely shelved those plans. OMB’s document says that under this current 30-year shipbuilding plan, the Navy would buy no additional aircraft carriers of any kind between the 2022 and 2026 Fiscal Years.

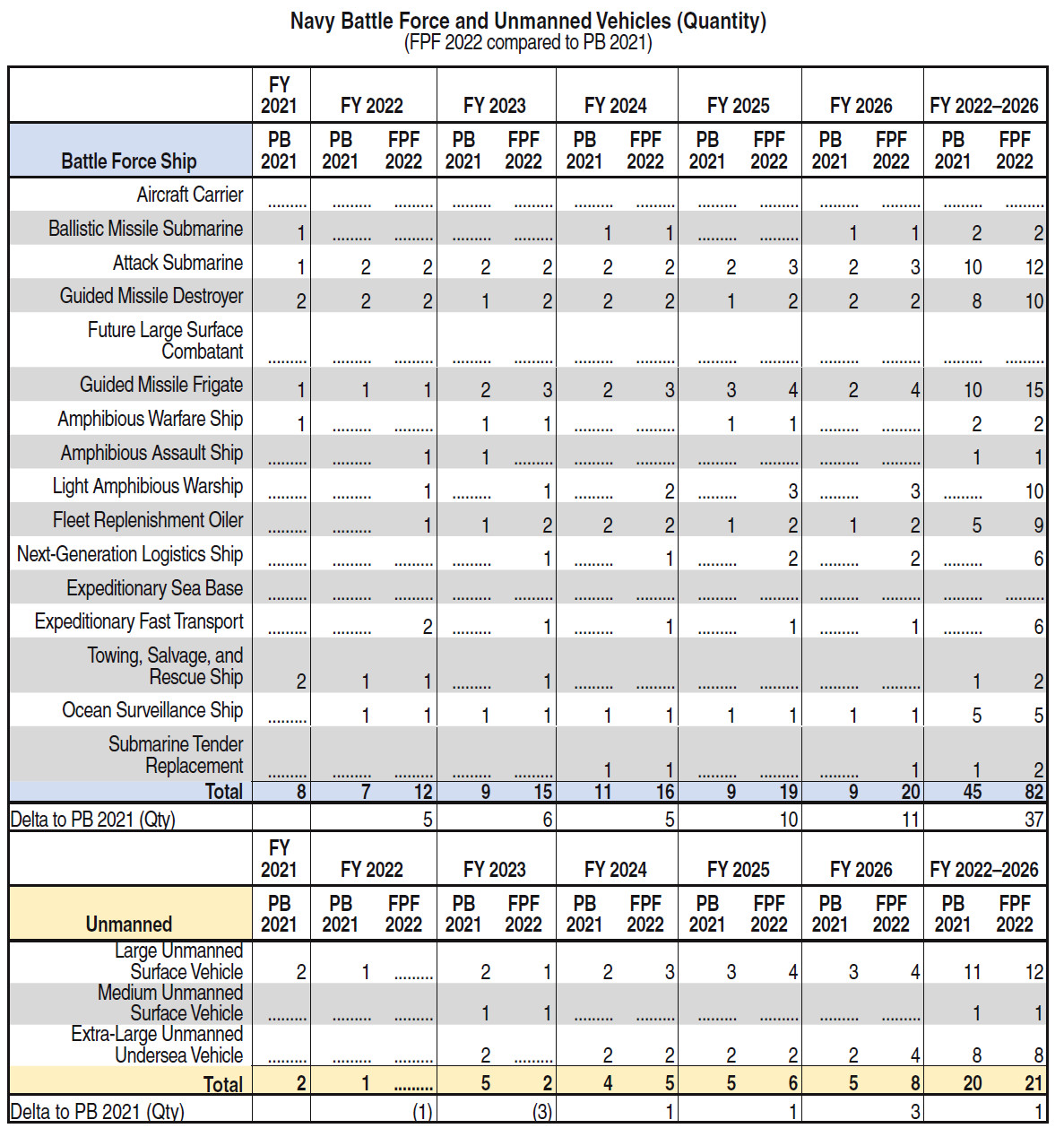

The plan also includes a notable increase in purchases of Constellation class frigates. Under this proposal, the Navy would buy 15 of these ships, up from 10, between Fiscal Years 2022 and 2026. In addition, the service would hire a second shipyard to help meet this increased demand, something that had been reported to be under consideration earlier this year.

Under this proposal, the Navy would buy slightly more Virginia class attack submarines and Arleigh Burke class destroyers in the Fiscal Year 2022 to 2026 time frame than previously planned, as well. It would also begin purchasing a new class of Light Amphibious Warship, which you can read about in more detail in this past War Zone piece, to support the U.S. Marine Corps’ new force structure plans and concepts of operation.

In addition, the plan underscores the Navy’s growing interest in unmanned platforms. The FPF shows an acceleration in the planned purchases of Large Unmanned Surface Vehicles (LUSV) starting in Fiscal Year 2024 and adding an additional LUSV to the total number to be ordered by Fiscal Year 2026.

OMB’s FPF says that the plan would see continued investment in the development and acquisition of both Columbia class ballistic missile submarines and a future attack submarine, presently known as SSN(X). The document says that the goal would be to buy the first SSN(X) by Fiscal Year 2034 and take delivery of that boat in Fiscal Year 2040.

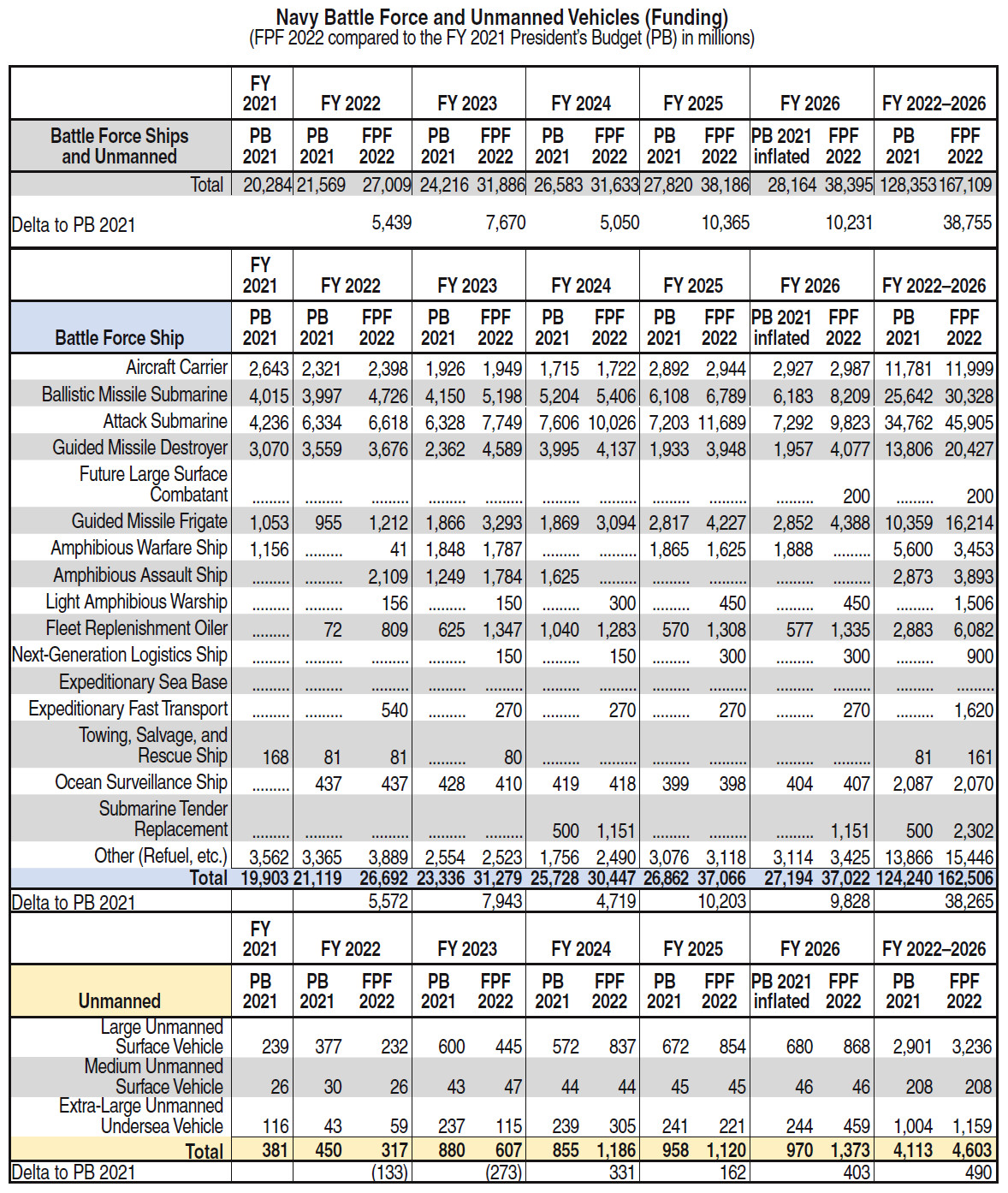

Overall, the FPF shows the Navy buying 82 new ships between Fiscal Years 2022 and 2026, almost double its planned acquisitions as laid out in its budget request for the 2021 Fiscal Year. A full breakdown of planned naval ship acquisitions under this proposal, by cost and the total number of hulls, as well as comparisons to the multi-year outlays in the Fiscal Year 2021 budget proposal, are seen below.

This 30-year shipbuilding plan also includes extending the service life of five Ticonderoga class cruisers and nine Los Angeles class attack submarines previously slated for retirement in order to support operational demands in the meantime. Discussions about the retirement of any Ticonderogas have typically turned into major political battles for the Navy in the past.

“The Chief of Naval Operations has emphasized that an increase in shipbuilding and the fleet size must be accompanied by investments in the ship-building industry, ship repair capabilities, and the resources needed to operate, train, and equip the fleet,” OMB’s document adds. “Therefore, the FPF proposes robust industrial base investments over the next 5 years, including: $2.8 billion within the shipbuilding account for shipbuilding and supplier base facilities to increase capacity; and $4.3 billion for the Shipyard Infrastructure Optimization Plan to ensure the Navy’s nuclear aircraft carriers and submarines are available to meet the Nation’s needs.”

This 30-year shipbuilding plan was also crafted in order to help the Navy achieve the long-standing, Congressionally-mandated goal of having a total fleet size of 355 ships and submarines by 2031. The service’s previously unveiled Battle Force 2045 proposal, which you can read about in more detail in this past War Zone piece, hopes to further increase that to 500 ships or more by 2045.

“By the Obama administration’s last year, after decades of cuts to shipbuilding and maintenance, the Navy had been stripped down to a fleet barely larger than it was 100 years ago,” OMB Director Vought and National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien wrote in The Wall Street Journal. “These 275 ships struggled to meet America’s national-security needs, leaving crews stressed, basic maintenance deferred, and the country at risk. The shipbuilding industrial base shrank to a fraction of the manufacturing might that won the Cold War.”

“Although less capable than ours, China’s navy already stands at more than 350 vessels and is growing rapidly,” the op-ed added, underscoring the significance of concerns about the continued growth of the People’s Liberation Army Navy, as well as the rest of the Chinese military, in current U.S. defense planning. “Beijing is building islands in the South China Sea, threatening trade routes, and menacing allies. U.S. maritime dominance is necessary to meet this great challenge.”

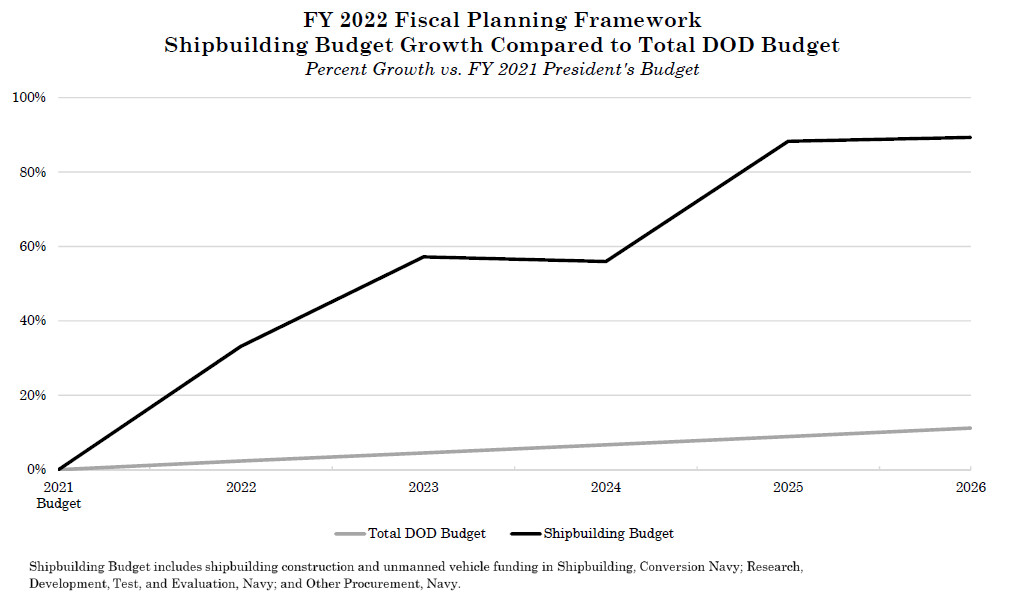

For this plan to work, the FPF says that the shipbuilding portion of the defense budget will have to increase by 85 percent between Fiscal Years 2022 and 2026, even as the total amount of defense spending is not expected to increase beyond around 15 percent in that same period.

OMB says that planned drawdowns in U.S. military operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere around the world will free up approximately $35 billion in the next six years. Another $7.7 billion would come from various reforms, “including the reduction of management and overhead costs,” according to the FPF. The Pentagon expects to find $6.6 billion in additional funds that it could redirect toward shipbuilding or other higher priorities through the retirement of various obsolete systems, including aging U.S. Air Force aircraft.

Most notably, though, the U.S. Army would see a significant cut to its overall end strength to help fund this new plan. The authorized end strength of the Army’s active-duty component would drop from around 492,000 to 485,000, while the Army Reserve would be capped at 189,500, ending previous plans to increase its size to 200,000. The approved size of the Army National Guard would shrink down to 336,000 from a past force structure cap of around 343,000. It is worth noting that the Army has had trouble meeting its recruiting goals to actually reach these force structure targets in recent years.

“Military compensation costs, which include pay and a wide range of healthcare, retirement, and other benefits, constitute roughly one-third of DOD’s total budget. These costs per person have grown at a much higher rate than the overall DOD budget,” OMB’s FPF argues. “Constraining end strength is one means of protecting the rest of the DOD’s budget to ensure America’s servicemembers have the modernized equipment and weapon systems to defend the Nation and prevail on the battlefield.”

However, this shipbuilding plan, some details of which had already leaked out to the press this week, has already drawn criticism, especially over the cuts to other services to pay for it. “These reductions [to the Army and Air Force] are completely unsustainable for any service, and will result in a hollow force if they remain,” one U.S. defense official told Defense One for a story published yesterday.

Navy leadership has reportedly objected to many of the components of the proposal, as well, especially the plan to not purchase a fifth Ford class aircraft carrier. The concern here is that the service could be left with just nine carriers by 2040, depending on how the work on a follow-on class of flattop goes. This would be toward the lower end of how many carriers the service determined it needed in a force structure study it concluded earlier this year and would be well short of the long-standing Congressional mandate to have at least 12 carriers in service.

It very much remains to be seen how much, if any, of this 30-years shipbuilding plan, as well as the Battle Force 2045 proposal, might actually get implemented in the coming years. There has been talk about potential defense spending cuts after President-Elect Joe Biden takes office in January, though its unclear how steep they may turn out to be. Biden himself downplayed the idea of curtailed defense budgets while on the campaign trail.

The decision to release details about shipbuilding priorities now is already highly irregular, as this usually goes to Congress along with the annual defense budget proposal in the Spring. There have been suggestions that this is, at least in part, a political move on the part of the Trump Administration to try to exert its influence on the process ahead of the hand off the incoming Biden Administration. Vought and O’Brien’s The Wall Street Journal op-ed includes considerable plaudits for Trump personally in regards to the shipbuilding proposal, though it’s unclear how much involvement the President had in its development.

Even in its final weeks, the Trump Administration is at odds with Congress over defense priorities and spending, broadly, with the President threatening to veto a current version of the annual defense policy bill, or National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), for Fiscal Year 2021. Trump and his Administration have objected to multiple provisions in the legislation, especially a requirement for the Army to develop a plan to rename bases currently named after generals who fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War.

With objections to the shipbuilding plan already coming from inside the U.S. military, it seems very likely that the proposal will see at least some changes after the Biden Administration takes over next year.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com