The Air Force only received its first two HH-60W Jolly Green IIs in November, but the service is already looking to upgrade its newest combat rescue helicopters. Many of the proposed additions are already found on helicopters and other platforms across the U.S. military and the service says that the Jolly Green IIs need at least one of the desired improvements to be able to effectively carry out their core combat search and rescue mission set at all. A major reason that these helicopters lack this and many of the other desired capabilities is that they are being built to requirements the Air Force laid out nearly a decade ago.

The Combat Rescue Helicopter Division of the Air Force Life Cycle Management Center’s Helicopter Program Office first announced on Oct. 1, 2020, that it was looking for companies to make various improvements to the HH-60W, as well as provide other upgrades, including to training simulators, and services in support of those helicopters. The Air Force’s 347th Rescue Group, part of the 23rd Wing at Moody Air Force Base in Georgia, took delivery of the first two HH-60Ws, out of a planned order of 113, on Nov. 5. The Jolly Green IIs are set to replace the service’s existing HH-60G Pave Hawks, which first entered service in the 1980s and are becoming increasingly more difficult to operate and maintain.

“This SSS [sources sought solicitation] will gather information on the current experience and capabilities of prospective industry sources to address CRH capability upgrades,” the contracting notices explained. Though the Air Force has no firm plans to pursue any specific upgrades, proposals it receives “could be addressed under a five-to-ten year capability upgrade contract” in the future.

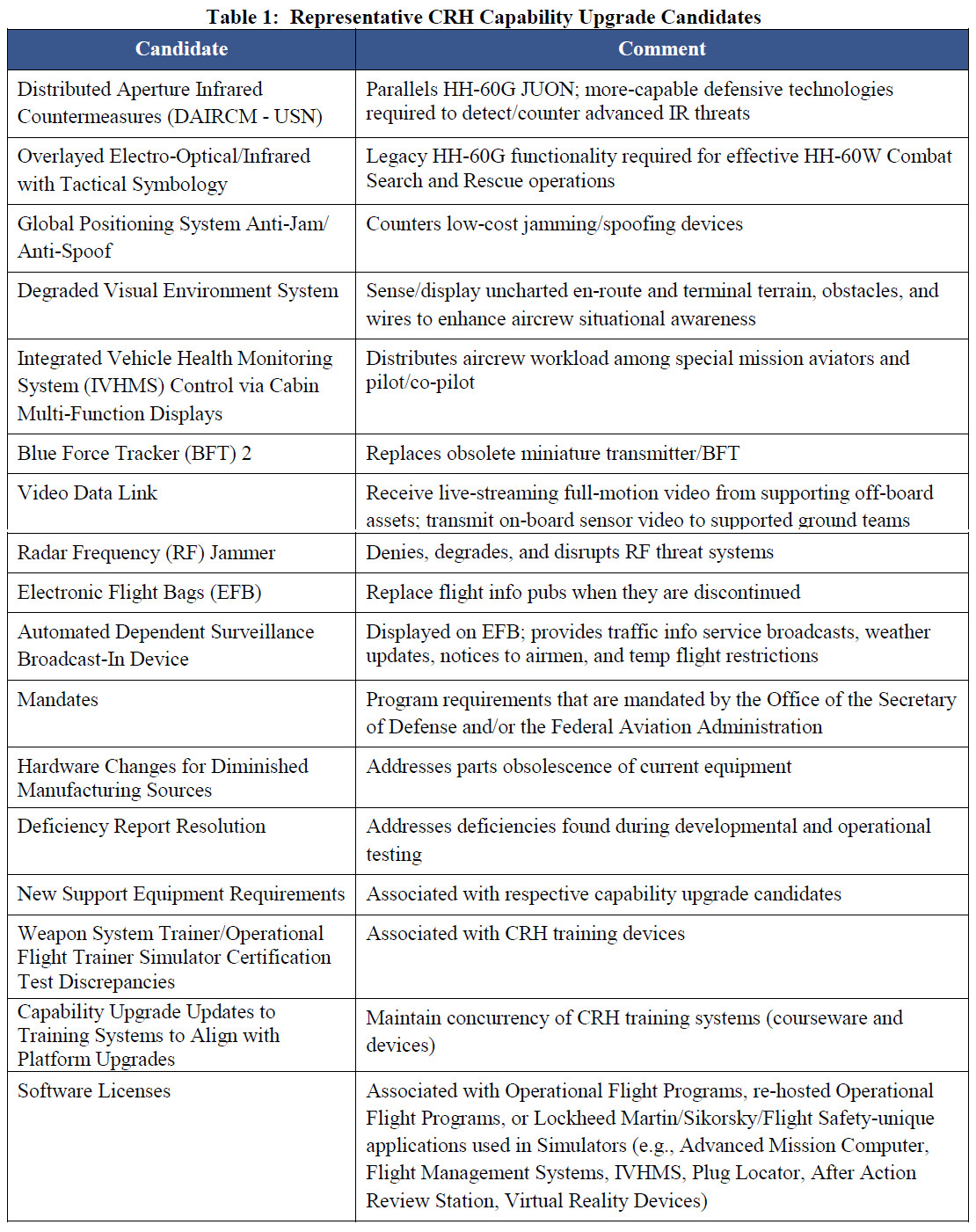

The notice includes 17 prospective “candidates” for upgrades to the HH-60W and associated items, which are seen below.

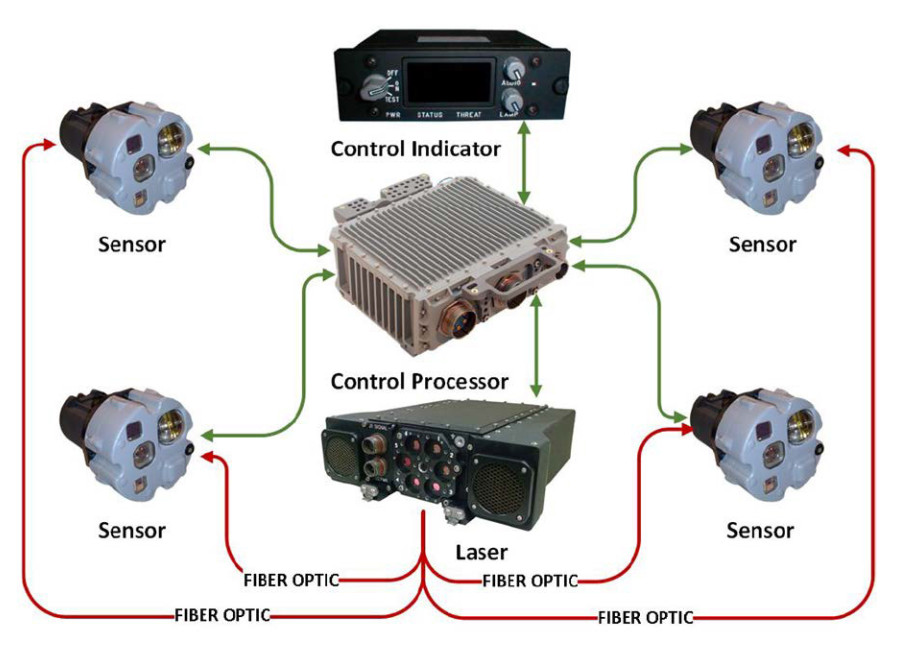

The very first item noted is a desire to add a Distributed Aperture Infrared Countermeasure System, or DAIRCM, developed for the Navy to the HH-60W. This is most likely the AN/AAQ-45, which uses multiple electro-optical and infrared sensors positioned around a helicopter to spot and track incoming missiles, and then uses a laser to blind and confuse infrared-guided seekers on many of those weapons, throwing them off course. The system also has the ability to detect other kinds of incoming missiles from the heat signature of their rocket motors, as well as alert the crew that their helicopter is being painted by an enemy laser or targeted by small arms, larger automatic cannons, or other fire from the ground.

Leonardo DRS Inc., the American subsidiary of Italian defense contractor Leonardo, has been working on this system for the Navy since at least 2016 and it has already been fielded on some of that service’s helicopters, as well as others belonging to the U.S. Marine Corps, Air Force, and Army, on a limited basis in response to an earlier Joint Urgent Operational Needs Statement (JUONS). In July, Naval Air Systems Command awarded Leonardo DRS a contract worth up to $120 million to continue developing this system and making improvements.

It’s worth noting that, while the AN/AAQ-45, is a relatively recent development for the U.S. military, other such directional infrared countermeasures systems have been in service for decades now, including on helicopters across the services. Marine VH-60Ns have long had this capability and the Army, as well as the Navy, have been working to add similar countermeasures to various H-60 variants, as well as other helicopters, for years now. Some HH-60Gs, which the HH-60W will supplant, are now among those already flying with the AN/AAQ-45 installed, as well.

This contracting notice from October also indicates that the HH-60Ws lack an electronic warfare jammer that could be used against enemy radars. This, together with the absence of the AN/AAQ-45, seems particularly notable for a helicopter that is ostensibly intended to operate in contested environments.

The desired ability to overlay tactical symbology on the electro-optical and infrared video feeds from the Jolly Green IIs nose-mounted sensor turret is another capability that the existing Pave Hawks have now, according to this contracting notice. It is a “functionality required for effective HH-60W Combat Search and Rescue operations,” according to the service, as well.

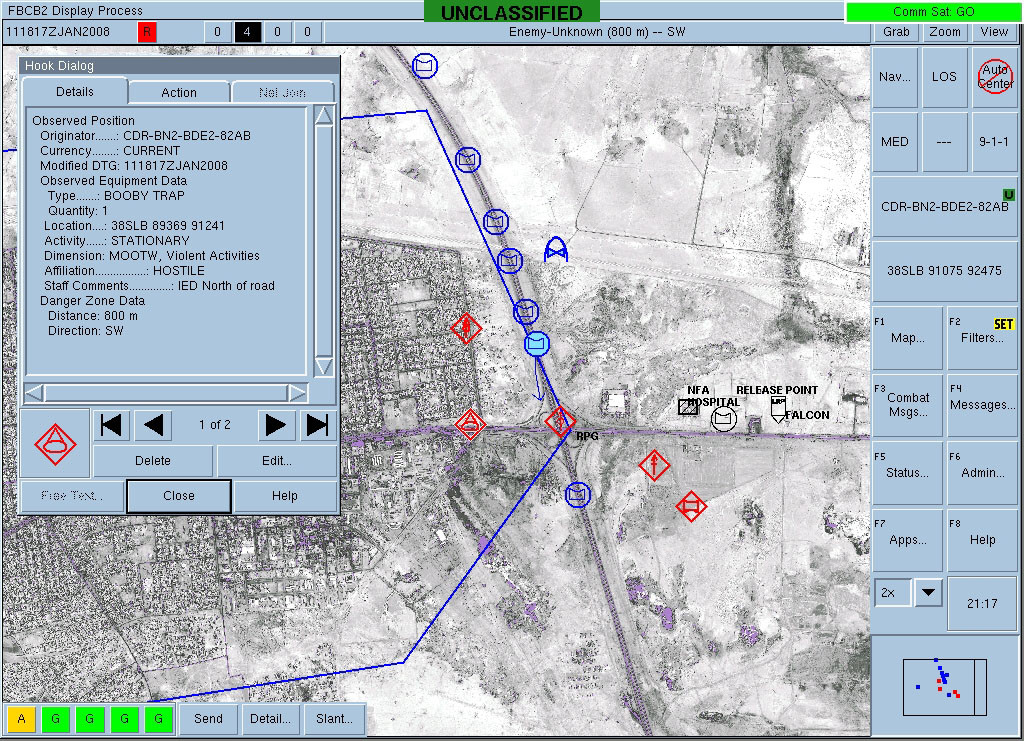

Other capabilities the Air Force says it wants to add to the HH-60W are already found on platforms across the U.S. military, including other helicopters, some of which are also variants of the H-60 family, as well. The Army, which manages the Blue Force Tracker (BFT) program, was well in the process of fielding the improved BFT 2 system in 2011. BFT 2, like its predecessor, is a networked system that allows equipped units to rapidly discern each other’s positions, as well as mark objectives, possible locations of enemy units or other hazards, and objects of interest on a common map, greatly improving overall situational awareness.

It’s not clear what level of Degraded Visual Environment (DVE) capability the Air Force might want for the HH-60W, but again, this is a capability that the Army, in particular, has already been working on for various helicopters, including H-60 variants, for some time now. It is worth mentioning, of course, that the systems that exist now, generally offer a relatively limited “soda straw” view in only one direction at a time and there are projects in development now that will offer significantly improved visibility in various environmental conditions and at night.

Still, having some DVE capability now would be better than none for HH-60W crews, who will be expected to regularly fly after dark where the dangers from overhead power lines and other hazards are even more pronounced. Such a system would also help improve situational awareness in conditions where a landing zone, or parts of the route there, may be obscured by smoke, dust, or other clouds of debris, including those kicked up by the helicopter’s own rotor wash.

It’s also interesting to note that the HH-60W apparently lacks the ability to receive video feeds from off-board platforms or transmit the streams from its sensor turrets to personnel on the ground. The ability to exchange this kind of information can be immensely valuable for coordinating with teams down below during missions. In terms of pushing video to ground units, at least, this is a capability that has been available to at least some degree for nearly two decades now through successive versions of the Remotely Operated Video Enhanced Receiver (ROVER) system.

The Air Force says that the absence of these and other capabilities on the HH-60W are in large part due to the fact that the requirements for the Combat Rescue Helicopter (CRH) program were firmed up in 2012. “The CRH requirements were baselined in 2012 prior to contract award of its Engineering and Manufacturing Development (EMD) phase,” the October contracting notice noted.

“The current system specification reflects the 2012 requirements baseline,” it continued. “During EMD execution, this requirements baseline has continued to evolve—driving the need for planning in support of a new contract vehicle to address a broad spectrum of known and undefined operational capabilities.”

It’s certainly fair to say that at a certain point in the development of any aircraft or other piece of military hardware, requirements have to get nailed down, just as a matter of practicality. Otherwise, constantly evolving realities could easily prompt new requirements that would in turn force design changes that would most likely lead to schedule delays and cost growth. The Air Force was clearly determined to avoid any unnecessary hiccups with the CRH program, which was the last in a string of efforts dating back to 2000 to replace, or at least supplement, the aging HH-60G fleet, a saga you can read about in more detail in this past War Zone piece.

Some of the desired improvements listed in the October contracting notice, as well as associated developments, are newer emerging requirements or concerns. For example, the importance of GPS receivers that are jam and spoof resistant has significantly grown in recent years.

The U.S. military, as a whole, is also increasingly becoming concerned about the general obsolescence of various kinds of components, in general, and the difficulties and costs associated with acquiring replacement stocks as time goes on. This applies, in some ways, to the software licenses question, as well. Matters of intellectual property rights to the computer code that increasingly runs advanced aircraft and other weapon systems has become a more common point of dispute between the Pentagon and defense contractors, especially Lockheed Martin, now the parent company of Sikorsky, which makes the HH-60W.

At the same time, as already noted, many of these upgrades the Air Force is eyeing for the HH-60Ws were available in 2012, at least in some form, or were already planned for the HH-60Gs. In addition, when it comes to advanced versions of ROVER and BFT 2, the Air Force has been looking to add those capabilities to the Pave Hawks for years now, as well. Just in August, the service issued a notice announcing its intention to buy ROVER VI and BFT 2 systems for existing HH-60Gs, which are still expected to continue flying for some time until sufficient numbers of HH-60Ws enter service.

The October contracting notice also highlights the need for fixes to deficiencies found during developmental and operational testing that appear to have gone unresolved, despite the Air Force now beginning to receive its first HH-60Ws. “Qualification testing of many components of the aircraft has uncovered technical deficiencies. As a result, the program began flight test with a large number of CRH-specific systems in non-operationally representative configurations,” the Pentagon’s Office of the Director of Test and Evaluation said in its report covering testing and evaluation of major weapon systems in the 2019 Fiscal Year.

That report did say that some improvements had been made to various key survivability features, including cabin and cockpit armor packages and self-sealing fuel hoses in the aerial refueling probe, but indicated some other issues remained. “Poorly designed hover symbology does not provide necessary safety-of-flight cues in degraded visual environments” and “Qualification testing of the fuel cell caused substantial hydrodynamic ram damage to the test article, necessitating repairs and analysis of system impact prior to continued testing.”

There is a “contractual specification to meet the reliability requirement roughly 2 years after IOT&E [initial operational test and evaluation], but the projected reliability during IOT&E may not meet the requirement,” the report added, regarding the general reliability of the helicopter. “The Program Office has modified the acceptance criteria to allow some fuel cell leakage to be considered a pass of the specification.”

It’s not immediately clear what of these remaining issues may have been further rectified in the 2020 Fiscal Year. The October 2020 contracting notice makes clear that at least some deficiencies with the HH-60W identified in earlier tests are still unresolved.

All of this can only raise questions about the exact operational utility of the HH-60Ws that are entering service now. It’s unclear when the Air Force expects to declare initial operational capability (IOC) with the type. As of 2018, the goal was to have done so by September of this year, but that did not turn out to be the case, with the service only taking delivery of the first two examples two months later.

The immediate need for all of these upgrades to the HH-60W also distorts the true cost of each one of these helicopters, no matter how much baselining the requirements back in 2012 may have helped control costs. It seems hard to believe that the Air Force was unaware from the beginning that it would need at least some amount of additional funding after the first helicopters arrived to ensure that the entire fleet was truly capable of performing their intended missions.

There has already been discussion, including here at The War Zone, about how capable a traditional helicopter, such as the HH-60W, will be in any future combat search and rescue scenario, especially against a higher-end opponent with a more robust integrated air defense network. If those threats demand the employment of stealthy combat aircraft, which are themselves not entirely immune to them, one would imagine they represent an even more significant danger to a very non-stealthy helicopter. With this in mind, the Air Force has already begun to explore more novel means of recovering downed pilots and other personnel, including from within denied areas.

There’s no denying that the Air Force’s HH-60G fleet is in need of replacement. It remains to be seen, however, how long and how much additional funding it will take for the HH-60W, which lacks many important capabilities in its present form, including some that the older Pave Hawks have, to reach its full potential.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com