The horn went off at 0330. Groggy, the pilot pulled on his flying suit, stuffed his feet into his boots, and headed down the stairs to Hangar 6. He was not alone.

As he clambered up the stairs through the jet’s gaping cargo door, he saw the alert mission crew getting settled into their seats. In the cockpit, he passed the two navigators already at work. The Nav 1 was spinning up the LN-20 stellar-inertial doppler system as the Nav 2 was prepping the SATCOM and her mission materials.

He slid into the left seat just as the copilot arrived. Both put on their headsets while strapping in.

“Pilot? Ground. Air stairs clear, ready to back.”

“Roger, brakes released.”

The copilot keyed the radio. “Six weather.” Transmitting in the blind, ground control broadcast the current weather conditions.

Now pushed outside of the huge hangar, the pilot began the engine start.

“Turning three.” The number three engine quickly came to life, followed by four, one, and then two. The crew entry chute closed and the airplane blinked as the copilot switched to internal power while the ground crew disconnected the ground power cart.

The jet moved onto the runway, turning left. Illuminated by the taxi lights, the pilot could barely see the edge of the runway in the fog and blowing snow. As the end of the runway disappeared under the nose, the pilot turned the airplane around sharply to align it with the centerline of Runway 28. The copilot turned off the taxi lights and the jet came to a stop. Flaps set, takeoff data reviewed, Before Takeoff Checklist complete. The pilot nodded in the dim red glow of the cockpit and the copilot switched on the landing light. Throttles set, all four engines steady, brakes released. Slowly, 285,000 pounds of airplane, crew, and jet fuel accelerated to 165 knots before rotating and disappearing into the frigid darkness.

The Cobra Ball was airborne.

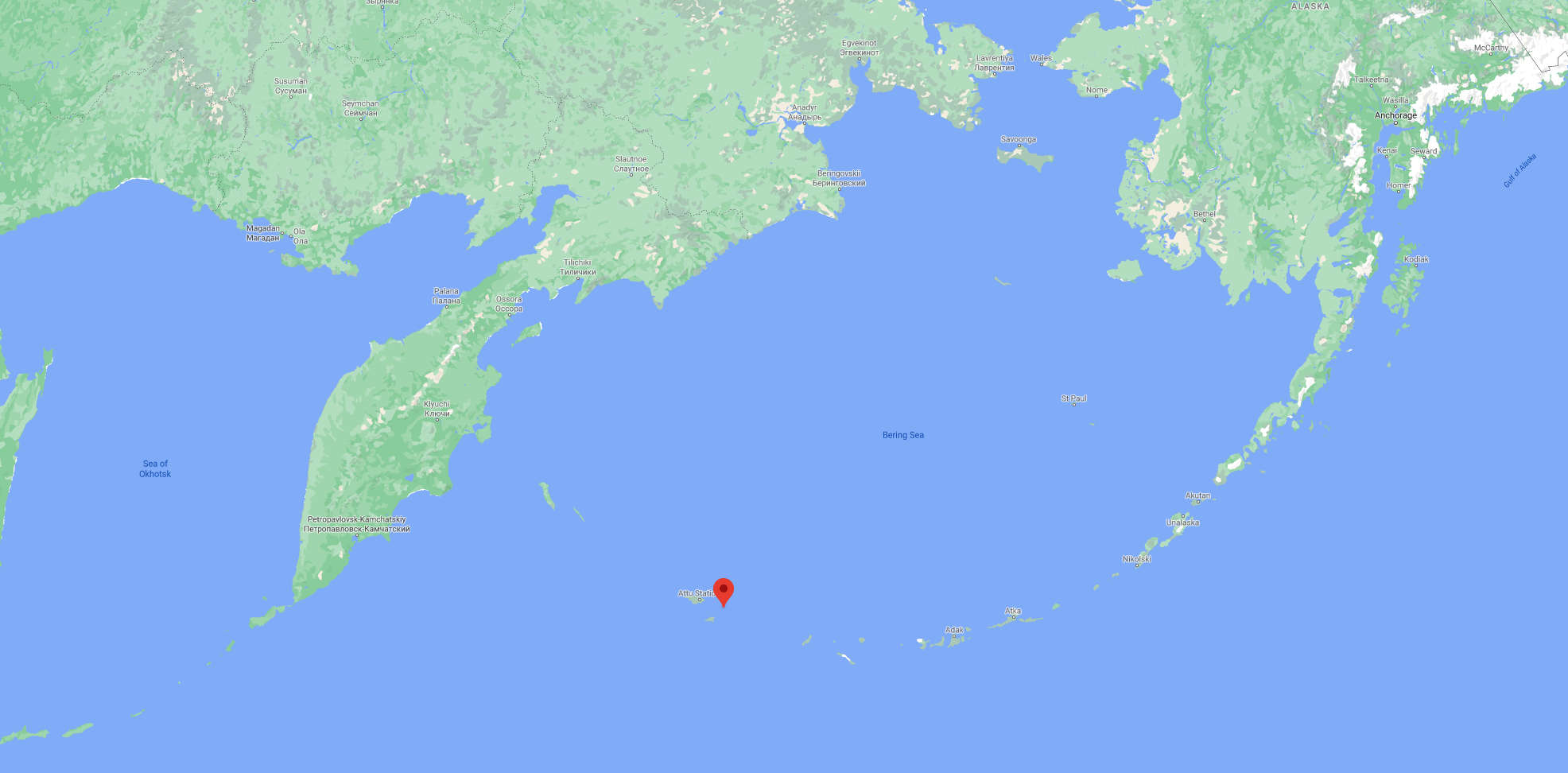

The Rock

Shemya Air Force Base, Alaska—better known as The Rock—sits on a remote island at the tip of the Aleutian Chain close to what was then the USSR. This location would allow the Cobra Ball and its crew to be in position less than an hour after notification to gather re-entry intelligence on Soviet ballistic missile warheads careening through the atmosphere during their terminal stage of flight.

The duty crew was ready to launch in less than 15 minutes, which occasionally gave them only 15 minutes for a “turn short” and collection of intelligence data once on the scene, that is if there was insufficient warning time from the Defense Special Missile and Astronautics Center (DEFSMAC), part of the National Security Agency. DEFSMAC determined that a Soviet launch was imminent. Normally, crews had a minimum of 30 to 45 minutes to be on station prior to collection. In many cases, however, the mission was a bust as the Soviets elected not to launch or the indicators at DEFSMAC were ambiguous.

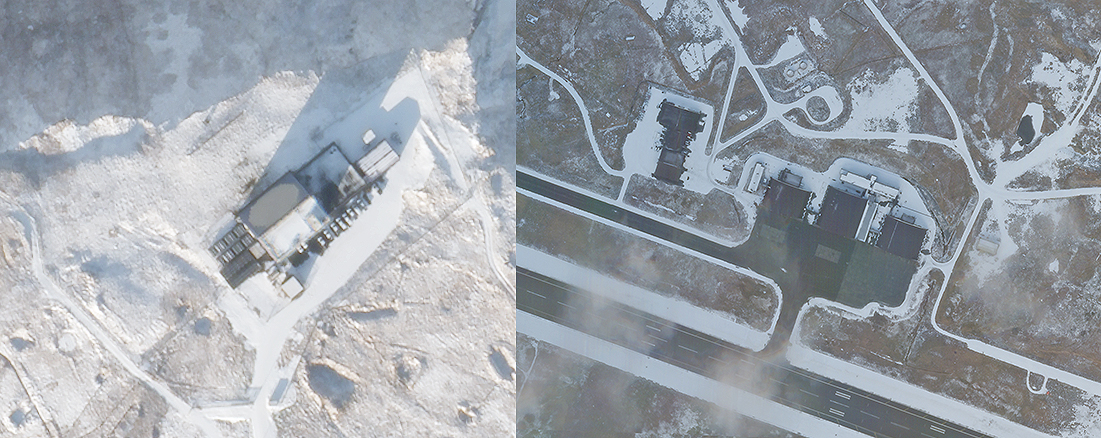

The Rock was cold, grey, and blustery, buffeted by wind, snow, rain, and fog. Two crews lived in rooms in the second story of the hangar and cooked their own meals in a common kitchen. Each crew deployed for two weeks at a time, with one-week overlap for continuity.

There was comparatively little to do on The Rock, which had one cable TV channel that showed old VHS movies and the Alaska Weather Report. Crews could visit the small base exchange, known as “Macy’s,” for a pizza, work out in the gym in the hangar, jog the length of the 10,006-foot runway, or tour the island.

When the weather was bad, the jet was back at Eielson Air Force Base on the Alaskan mainland, there was no tasking, or after a mission, crews were rewarded with a “Beer Light” to raise their spirits. A cold beer or two sometimes led to hijinks like riding the rotating beacon on the top of Hangar 3 or the ritual skinny dip in the frigid Northern Pacific Ocean followed immediately by similar immersion in the Bering Sea.

Road To Cobra Ball

In 1959, the United States began collecting telemetry intelligence (TELINT) of Soviet ballistic missile launches. These initially involved EB-47E(TT) Tell Twos operating from Incirlik Air Base in Turkey and flying over the Black Sea and Iran. In addition, spooky U.S. Navy aircraft operated from bases in Pakistan, but were soon evicted. Despite their successes in collecting boost-phase TELINT, all of these planes lacked any optical capability. Moreover, they only tracked the missile booster and not any re-entry vehicles (warheads).

To mitigate this shortcoming, in 1960, the U.S. modified a four-month-old Boeing KC-135A, serial number 59-1491, with only 142 total hours into a configuration nicknamed Nancy Rae to collect measurement and signature intelligence (MASINT). On December 31st, 1961, the airplane and crew arrived at Shemya AFB. Over time, the airplane was redesignated as JKC-135A and later RC-135S, and the program name changed to Wanda Belle, then to Rivet Ball, and finally to Cobra Ball.

The sole Lisa Ann RC-135E, serial number 62-4137, later renamed Rivet Amber, joined the Rivet Ball in 1966. This new airplane carried a massive Hughes radar to track incoming re-entry vehicles, which were then filmed by a ballistic streak camera similar to the one on the Rivet Ball.

Tragedy struck on January 13th, 1969 when the Rivet Ball slid off the runway at Shemya AFB, breaking its spine, but with no loss of life or equipment. Months later, on June 5th, 1969, the Rivet Amber aircraft disappeared over the Bering Sea with the loss of all 19 crewmen onboard.

To make up for the loss of those aircraft, two former testbed C-135Bs, serial numbers 61-2663 and 61-2664, were hastily converted into RC-135S platforms, entering service in 1969 and 1972, respectively. On the Ides of March 1981, 61-2664 struck the approach lights of Runway 10 during landing at Shemya AFB, killing six of its crew.

While in the hospital recovering from an assassination attempt, President Ronald Reagan subsequently approved the emergency conversion of another C-135B, serial number 61-2662, into the fourth Cobra Ball, attesting to the critical national importance placed on these airplanes and their mission.

In 1989, as part of the Strategic Defense Initiative, the lone RC-135X Cobra Eye, serial number 62-4128, arrived at Shemya AFB. The Cobra Eye flew missions on behalf of the U.S. Army and U.S. Ballistic Missile Defense agencies. With the end of the Cold War, it was eventually reconfigured into an RC-135S, one of three that are still in service, at the time of writing, with the 55th Wing at Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska.

The most distinctive feature of the Cobra Ball is its black starboard wing and engines. This was initially done to reduce glare on the mission optics, although with newer equipment this became less important, if not altogether unnecessary. Beginning with the conversion of 62-4128, the Cobra Balls have been configured with bilateral digital sensors allowing collection from either side of the aircraft. The black wing has been retained both out of a sense of tradition and as a clear indicator that the airplane is a National Technical Means of verification asset.

Ready To Collect

After nearly four hours of tediously drilling holes in the night sky 40 nautical miles off the east coast of the Soviet Union’s Kamchatka Peninsula, the Cobra Ball headed off to air refuel from the strip alert KC-135A on temporary duty with the Alaskan Tanker Task Force at Eielson Air Force Base, also the home base for the Strategic Air Command (SAC) Cobra Ball crews assigned to the 24th Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron, part of the 6th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing, and crews assigned to the 6985th Security Squadron, part of Electronic Security Command, then the Air Force’s component of the Central Security Service. The “Ball” returned to its orbit area just before sunrise. It looked to be another “Tuna Patrol,” with no collection.

Suddenly the Tactical Coordinator came over the intercom, “X-Ray! X-Ray! X-Ray! Crew, we have a launch from Plesetsk of an SS-18 Mod 5. Re-entry objects are the bus and up to 10 warheads, including decoys and other junk. ETA 28 minutes.”

The pilot switched off the autopilot altitude hold and began a slow climb to flight level 350. Now fat with gas from the tanker, it would take a big chunk of the next half-hour to climb as high as possible to reduce atmospheric interference with the Real Time Optical System (RTOS) and Multiple Object Discriminator System (MODS) that visually tracked whatever survived re-entry.

The Navs quickly calculated how to position the jet so it would be at the top of its orbit (the northernmost point) exactly two minutes prior to re-entry. At the time, the Cobra Ball had its optical sensors only on the right side of its fuselage, so they needed to head south to view the re-entry at the Kura Test Range to the west. Flight parameters were critical: zero degrees deviation on heading, less than two knots of airspeed and two degrees of bank, with less than a 50-foot variance in altitude. Knowing exactly where the Cobra Ball was in three-dimensional space relative to the re-entry revealed considerable details about the objects it tracked.

Some 30 seconds after turn-down, both the copilot and the Photo Technician keyed their interphones.

“Gaslight! Gaslight! Gaslight!” The first object became visible, leaving a fiery streak in the Western sky. Each object left a similar long streak from the upper atmosphere, downward to the impact area on Kamchatka, which they struck in the pre-dawn darkness. In the back end of the jet, cameras whirred and telemetry tapes filled up. The copilot used a grease pencil on his side window to trace the re-entry pattern of all the objects which would be transcribed to the mission report for further analysis by the scientists of the Foreign Technology Division at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio.

In less than a minute it was over.

Each crewmember sat hunched over their stations, filling out forms, copying key data, and summarizing the performance of the equipment.

There was only one “window” today, meaning there would be no further launches. It would soon be time to go home.

Returning To Base Can Be The Hardest Part

Landing at The Rock has always been a challenge.

When it was originally built during World War II to support B-24s and P-38s, there were two perpendicular runways to deal with the strong crosswinds that buffeted Shemya, located at the confluence of the Northern Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea. Now there was just one, and the crosswinds were wicked.

Storms could last for days with gale-force winds, rain, sleet, snow, and dense fog, often all at once. The hangar doors could only be opened if the winds were less than 50 knots, so more than a few sorties were canceled for bad winds alone. In minutes, the weather at Shemya could change as the front moved through, leaving the island bathed in balmy 40° sunlight and calm winds. Back home at Eielson AFB, it could be -40° with dense ice fog.

At the beginning of Nancy Rae operations, the flight crews were all highly experienced Majors or Lieutenant Colonels from Air Force Systems Command. When SAC took over the mission, this level of expertise continued, but, by 1965, copilots with two or three years of experience were assigned to the right seat.

An incident in 1966 restricted the copilot upgrade process, reaffirming the need for well-seasoned ‘135 pilots in the left seat. Eventually, these new upgrade limits were relaxed given the assumption that experienced Shemya-qualified copilots could safely transition to become experienced Shemya-qualified aircraft commanders. The crash of RC-135S 61-2664 at Shemya AFB in 1981 by one such pilot permanently ended copilot upgrades.

Subsequently, SAC required each Cobra Ball aircraft commander to have a minimum of 2,500 hours of total time, be qualified as an instructor pilot, and complete a rigorous check-out procedure in order to land at Shemya AFB. This applied to all SAC aircraft, including transient KC-135s. Cobra Ball copilots typically upgraded to aircraft commander en route to their next assignment. With the cessation of operations from The Rock, the unit moved to Offutt AFB in 1995 as part of “Cobra Thaw” and this requirement went away.

Recovering On The Rock

As the Ball approached 130 nautical miles from Shemya AFB, the Nav 2 updated the weather via the SATCOM. Runway 28 in use, winds two-three-zero at 25 gusting 30 knots, ceiling 800-feet and visibility one nautical mile with intermittent snow. Not bad, and certainly within the limit of 25 knots direct crosswind. The Cobra Ball could not begin its descent to Shemya AFB if the landing conditions were out of limits, and would instead orbit until it reached the minimum fuel level required to divert back to Eielson AFB.

“We’re golden,” said the pilot, “Before Descent Checklist.” The copilot prepared the landing data, the Navs completed their charts and paperwork, and the back-end crew finished shutting down their equipment. Passing 10,000-feet, the copilot called the checklist complete.

“Shemya, Blind 55, request vectors to the ILS, Runway 28.”

“Roger, Blind 55, turn left heading zero-four-zero and descend to 2,500.”

“Zero-four-zero, 2,500, Blind 55.”

As the Ball slowed below 220 KIAS (knots indicated airspeed) the pilot called for flaps 20° and the Before Landing Checklist. The Detachment Commander—Cobra 01—updated the winds and runway conditions. They were still within limits.

“Blind 55, turn left three-zero-zero and join the localizer.”

“Three-zero-zero, Blind 55.”

Presently the ILS localizer “came off the wall” and the pilot banked left to intercept the inbound course. With the winds this morning it would not be an airliner landing.

“Flaps 30°, gear down.” The copilot moved the flap lever and extended the gear.

“Three green, good pressure. Before Landing Checklist complete.”

Although it was now daylight, the pilots could see nothing but white in the solid overcast. In the back it was already a bumpy ride; a blindfolded roller coaster ride.

“Flaps 40°. Gear, flaps, fuel panel set for landing, safety checks complete.”

“Blind 55 is gear down, full stop.”

“Roger Blind 55, cleared to land.”

“Cleared to land, Blind 55.”

The Ball broke out of the clouds above the grey water of the Pacific Ocean, but there was nothing ahead of the nose. The copilot looked out his side window and saw the runway cocked off some 45° to the right.

“Runway in sight. Love this weathervaning.”

“Flaps 50°,” said the pilot, “Crew, continue to land.”

The airplane passed over the cove at the approach end of Runway 28. No wind shear this time.

The pilot lowered the left wing and pushed in a boot-full of right rudder to align with the runway. Some 2,000 feet down the runway the airplane landed hard, intentionally dissipating lift and momentum. Up went the speed brakes—putting even more weight on the landing gear—and the pilot pulled the thrust reverser levers into the armed position. Four lights on the instrument panel turned bright orange.

“All four! All four!” called the Nav 1. The roar of the thrust reversers signaled the back-end crew that the landing was indeed a full-stop.

After 7.1 hours, Mission S032 was over. A successful “take,” an uneventful landing, and a green Beer Light.

Shemya’s Cobra Ball Legacy

Over the years, details like these of the Cobra Ball’s mission have evolved as the airplane changed, new equipment and personnel were added, and mission requirements shifted. In 1988, the Cobra Ball deployed to Kadena Air Base on the Japanese island of Okinawa to monitor a launch by the People’s Republic of China. Following the 1995 termination of operations from Shemya AFB, the RC-135S fleet was re-engined and upgraded. The three jets and their crews have since monitored missile launches by Russia, China, India, Pakistan, Iran, Syria, and North Korea.

The legacy of the Cobra Ball mission lies in its ongoing efforts to understand foreign ballistic missile development and the resulting diplomatic processes to limit their threat to the United States and its allies. As one of America’s National Technical Means of verification, the value of the Cobra Ball and its crews remains unequaled.

Robert S Hopkins, III, flew the RC-135S and RC-135X as a copilot from 1987-1990. In 1989, he was part of the crew that flew the first operational reconnaissance mission of the RC-135X, for which they became the first RC-135 crew to receive the General Jerome F “Jerry” O’Malley Award for the best reconnaissance crew in the Air Force. Hopkins has written extensively about the Cobra Ball and other RC-135 operations.

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com