After much speculation and at least one false alarm, it seems we finally have a strong indication that at least one of China’s Xi’an Y-20 military transport aircraft is now flying with indigenous WS-20 turbofan engines, which offer more power than the Russian-made Soloviev D-30KP-2s fitted to earlier examples. If true, the development would represent a significant advancement in capability for the big airlifter, which first entered operational service in 2016 and is broadly analogous to the U.S. Air Force’s C-17 Globemaster III.

The new photo apparently showing the re-engined Y-20 seems to have been first posted to the Chinese microblogging website Weibo back on November 21, 2020, by a user named @茶水肥肥猫. More recently it was shared on other social media channels by, among others, Andreas Rupprecht, an expert on Chinese military aerospace and friend of The War Zone, who tweets as @RupprechtDeino.

Unlike a previous image that also emerged on social media on November 21, and which was later revealed to be manipulated, the new image appears to be the real deal. The new photo shows a Y-20, apparently still in primer paint, and with characteristic enlarged engine nacelles, accompanied over Xi’an-Yanliang Air Base by a J-11 Flanker chase plane — standard procedure for such a test flight.

China has already made rapid progress with the Y-20 program and production is now progressing at a prodigious rate. However, the airlifter, in its original iteration, has always been hamstrung by its obsolescent engines. The original Y-20A, dubbed “Kunpeng,” after a giant bird of Chinese mythology, is powered by four Russian-made low-bypass Soloviev D-30KP-2 engines, which are lacking in terms of thrust and efficiency compared to modern high-bypass turbofans.

It was always the plan to eventually install indigenous WS-20 high-bypass turbofans, allowing the Y-20 to achieve much more of its potential and remove dependence on a foreign engine source. The WS-20 is expected to deliver around 31,000 pounds of thrust, compared to 26,450 pounds for the D-30KP-2.

Previous analysis had suggested that the new engine might only be ready for limited production starting from 2024, which suggests that the program could have been accelerated, or perhaps has not faced the problems that had been envisaged. On the other hand, we have so far only seen likely evidence of a single re-engined Y-20 and while Xi’an may be capable of producing airframes in large numbers, it is not currently clear if the same applies to the WS-20 engines. Bearing in mind that jet engine technology is one critical area in which China has traditionally lagged behind its rivals, then it is possible that large-scale production of the new-generation turbofan could still be some way off.

The re-engined version of the aircraft for the People’s Liberation Army Air Force, or PLAAF, is likely designated Y-20B.

Even with its D-30KP-2 engines, the Y-20 can reportedly carry a maximum payload of 132,000 pounds, outstripping the 96,000 pounds carried by the PLAAF’s Russian-made Il-76 Candid airlifters. While the PLAAF secured around 20 Il-76s from Russia and other sources, Beijing’s inability to acquire more of these transports was also a major spur to the Y-20 project.

These figures also make an interesting contrast to the C-17. According to the U.S. Air Force, the C-17 has a maximum payload capacity of 170,900 pounds, which comfortably outstrips the Chinese transport, at least in its Y-20A form. The re-engined Y-20 might help to reduce that capability gap to the U.S. Air Force transport.

The significance of the Y-20 for the wider People’s Liberation Army, and Beijing’s geopolitical aspirations, lies in its ability to rapidly deploy both troops and cumbersome weapons systems, including the latest versions of the Type 99 main battle tank, over considerable distances, likely to be a crucial aspect of China’s new-look military strategy. The Y-20 also has the potential to deliver large amounts of other equipment and basic supplies to forward areas, to support sustained operations in a way that is routine for the U.S. Air Force C-17. As long as China continues to make pace as a global power, then the demand for the Y-20 can be expected to grow, too. Now, with new engines apparently soon to be available for production Y-20s, the aircraft will be better equipped to undertake these missions.

As well as purely military missions, the Y-20 has also already demonstrated its potential for humanitarian or other “soft power” applications, for example when it was used to bring medics and other humanitarian supplies to the Chinese city of Wuhan, the epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak, earlier this year. You can read all about that particular mission in this previous War Zone article.

In fact, so important to the PLAAF is the Y-20, that there are reports that Xi’an slowed down work on the secretive H-20 bomber program to refocus resources into the cargo plane. Only after work on the initial airlifter prototype wrapped up in late 2012 did the company return to the H-20 in earnest.

In the future, the Y-20B is also expected to form the basis of a new aerial refueling tanker, addressing another current deficiency in the PLAAF order of battle. An unconfirmed image of the Y-20 tanker variant, likely designated Y-20U, began to circulate recently, seemingly showing a J-20 fighter jet approaching the trailing hose-and-drogue assembly. So far, it’s not clear if this photo is genuine, but a tanker version of the transport can probably be expected sooner rather than later.

Once available, the Y-20U will complement the limited Il-78 Midas tanker fleet — just three second-hand examples — and will be especially useful for supporting PLAAF fighters on long-range patrol missions over the South China Sea and the eastern Pacific near Japan. It will also be a much more capable asset than the tanker conversions of the H-6 Badger bomber, which offer a comparatively limited fuel payload.

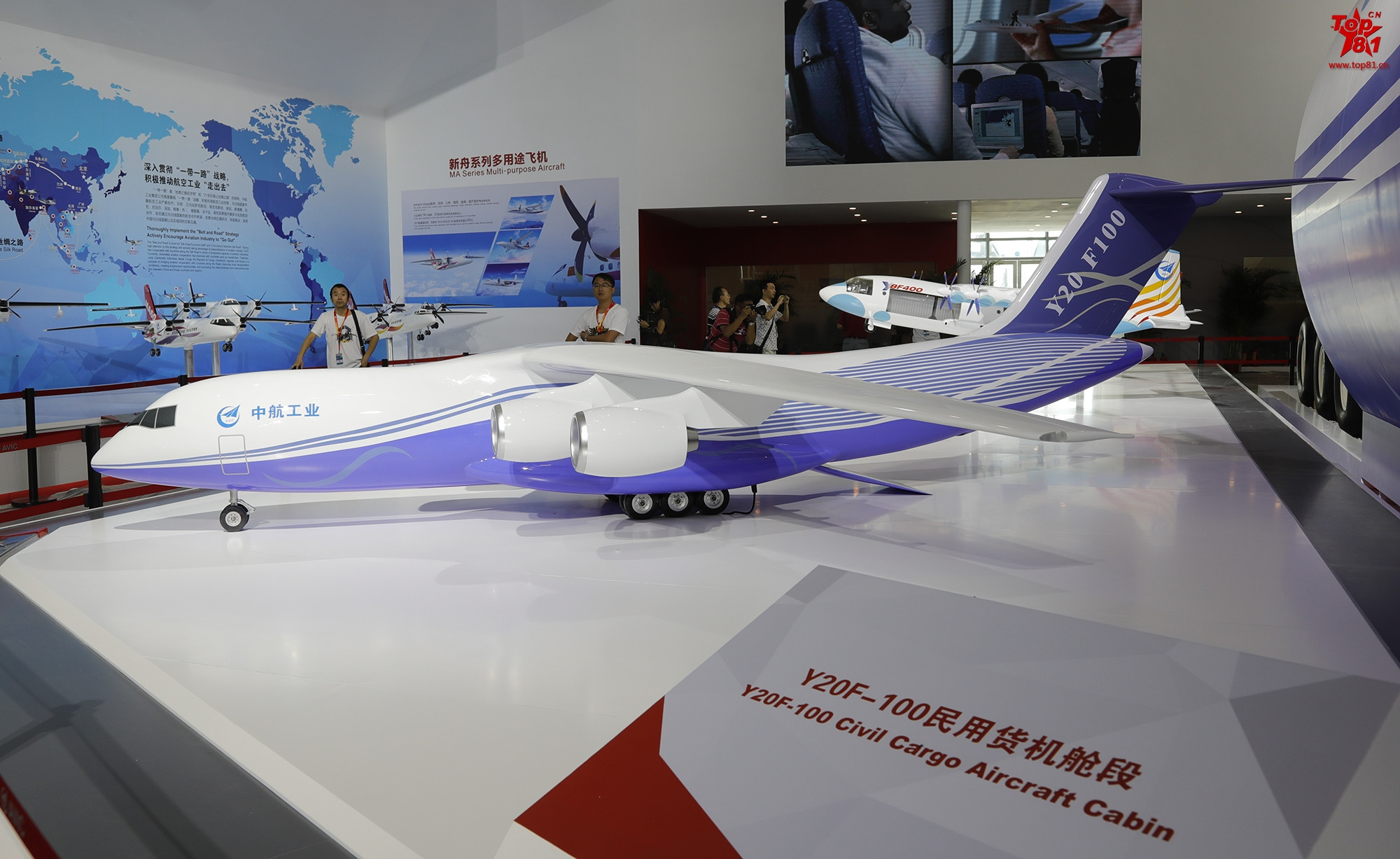

Other potential variants of the re-engined Y-20 include a proposed airborne early warning and control (AEW&C) platform and a civilian cargo derivative, which has previously been exhibited in model form, known as the Y-20F-100. In the civilian sector, the Y-20 perhaps even has the potential to displace the Il-76, which is currently a popular choice for commercial chartered airlift.

An AEW&C version could also be very useful to the PLAAF, which has again been hampered by the limited availability of Il-76s for modification to the KJ-2000 Mainring configuration. Currently, the service operates just four examples of the Mainring. A Y-20 AEW&C aircraft could supersede the KJ-2000 as a heavyweight counterpart to the AEW&C variants of the turboprop-powered Y-8 and Y-9 families.

Regardless of developments in the tanker and AEW&C realms, providing the re-engined Y-20 meets expectations, it seems the aircraft is well on its way to fulfilling the PLAAF’s strategic transport needs.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com