The U.S. government’s massive radio telescope in Arecibo, Puerto Rico, the second-largest such instrument in the world, has collapsed onto itself, effectively destroying it, but thankfully causing no injuries. While the site, construction of which was completed in 1963, is best known for its work in radio astronomy, most don’t realize it was originally built with support from the U.S. military in part to aid in the research and development of ballistic missile defense systems.

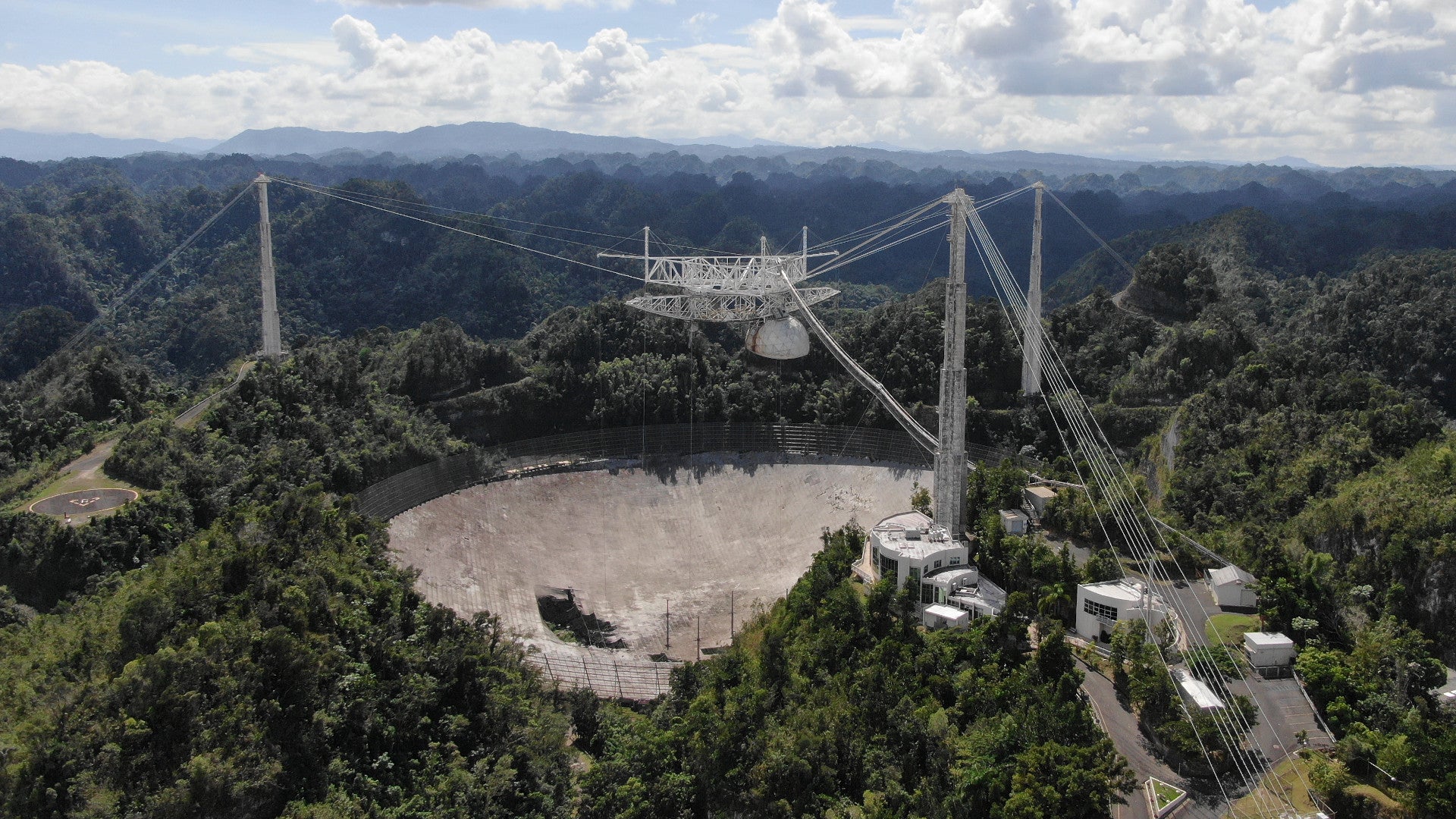

The National Science Foundation (NSF), the U.S. agency that presently owns the site, confirmed that the telescope’s triangular-shaped instrument platform, which weighs some 900 tons, had fallen onto the reflector dish over 400 feet below on Dec. 1, 2020. The instrument platform had been suspended above the dish using cables running from three towers, one of which was effectively sheered in half during the collapse. The tips of the other two were reportedly broken off, as well.

“The instrument platform of the 305m telescope at Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico fell overnight. No injuries were reported,” a post on NSF’s official Twitter account on Dec. 1 read. “NSF is working with stakeholders to assess the situation. Our top priority is maintaining safety. NSF will release more details when they are confirmed.”

On Nov. 19, NSF had already announced it would decommission the site following an assessment that showed the structure was too dangerous to operate or even attempt to repair. Cable breaks in August and November had already damaged the dish and raised the risk of collapse substantially.

“It sounded like a rumble. I knew exactly what it was,” Jonathan Friedman, who lives near the site and had worked there as a senior research associate for 26 years, told The Associated Press. “I was screaming. Personally, I was out of control…. I don’t have words to express it. It’s a very deep, terrible feeling.”

Radio telescopes are primarily designed to collect radio waves emanating from objects in space, or even in the very upper reaches of the Earth’s atmosphere, for various research purposes. They are also capable of “imaging” objects, ranging from galaxies to individual planets to asteroids “near” Earth, using these signals.

The Arecibo’s site origins trace back to the 1950s, when Cornell University proposed its construction to the Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), which is today known as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). A desire to better understand the composition of the ionosphere and how it might impact objects passing through, including ballistic missile reentry vehicles carrying nuclear warheads, was a key reason for its construction.

At the time, ARPA was in charge of a broad ballistic missile defense program known as Project Defender. It was believed that nuclear warheads would produce a distinct signature when reentering the atmosphere, making it possible to distinguish them from decoys, so long as that signature could be quickly identified and categorized. The plan was to use the Arecibo Telescope to help gather general, but still valuable information about the ionosphere in support of this effort. ARPA was also interested in using it for various radar-related experiments, as well. The telescope could still function as a general-purpose research tool, too.

William E. Gordon, a physicist and astronomer at Cornell, oversaw the telescope design, which originally consisted simply of the large reflector dish. The presence of large sinkholes in and around Arecibo made the area ideal for hosting this massive instrument.

However, ARPA was concerned that the initial plan would limit the telescope’s value, since it would have a fixed field of view. This led to further design studies and the eventual construction of the suspended instrument platform with a movable beam-steering mechanism. Work began on the site, which was originally named the Department of Defense Ionospheric Research Facility, in 1960 and operations began at what had been renamed the Arecibo Ionospheric Observatory in 1963. In 1973, upgrades were made to increase the telescope’s maximum operating frequency.

In 1997, a Gregorian reflector system was installed, allowing for improved focusing of incoming radio waves, along with a more powerful transmitter. This all gave the site the ability to take on a planetary radar role, including watching for potential hazards in space, such as incoming asteroids. The complete Arecibo Observatory complex also eventually included a facility hosting a space-facing laser imaging system and a visitor’s center.

Cornell University managed the site on behalf of NSF, with additional funding from NASA, between 1963 and 2011. During that time, the site supported various scientific research efforts, including the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) project. Researchers made their first attempt to contact an extraterrestrial species in 1974. During the Cold War, consideration had also been given to using the site for military intelligence purposes, including scooping up Soviet radar signals after they had bounced off the surface of the moon. The U.S. military did conduct similar indirect signals intelligence collection using fixed “Elephant Cage” antenna arrays positioned around the world.

In addition, Arecibo had something of a movie career, being the setting for the climactic showdown between Pierce Brosnan’s James Bond and Sean Bean’s Alec Trevelyan in 1995’s GoldenEye. It was also featured in 1997’s Contact, a dramatic film that was based on the real-life SETI program. It made an appearance in the 1995 science fiction horror movie Species and an episode of the hit television show The X-Files, as well. Video game developers also used the site as a set-piece over the years.

Despite the obvious and unique value of the Arecibo telescope, which remained the largest such instrument in the world until 2016, when China opened the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST), operations had already been in decline for more than a decade before this fateful accident last night. In 2006, NASA stopped providing supplemental funding to support the site, and the NSF officials recommended further slashing the budget for operating and maintaining the facility from $10.5 million in 2007 down to $4 million by 2011.

By 2007, the annual budget had already dropped to $8 million and NSF was considering shutting the entire facility down if it could not secure additional outside funding. In 2011, it did strike a deal with SRI International to take over management of the observatory complex from Cornell University and to help support its operation.

In 2017, Hurricane Maria caused significant damage to the telescope. NSF did not make an effort to restore all of the instrument’s capabilities after the storm, determining that repairs would have cost more than its annual operating budget. The next year, a consortium led by the University of Central Florida took over management of the site in a deal that included providing outside funding to help operate and maintain the site, with the hope that this would secure its future.

This, unfortunately, was not meant to be. The first cable failure in August of this year left a 100-foot long tear in the reflector dish and the second cable break in November smashed a larger hole in the dish. There had already been concerns about the stability of the structure after the first cable snapped and the on-site engineering team, in consultation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, subsequently deemed the site unsafe to work in.

It’s unclear how NSF may now look to replace this lost capability, but, no matter what, the collapse certainly marks a sad end for this particularly unique scientific instrument that was born out of the Cold War.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com