The U.S. Army is looking at developing a network of high-altitude balloons that would fly in the stratosphere and be able to launch swarms of unmanned aircraft, including those configured as loitering munitions, also known as “suicide drones,” over enemy-controlled territory. These lighter-than-air vehicles could also be configured as sensor platforms to collect various kinds of intelligence or deploy other surveillance systems that would fall to the ground in order to monitor hostile movements, as well as act as communications relays.

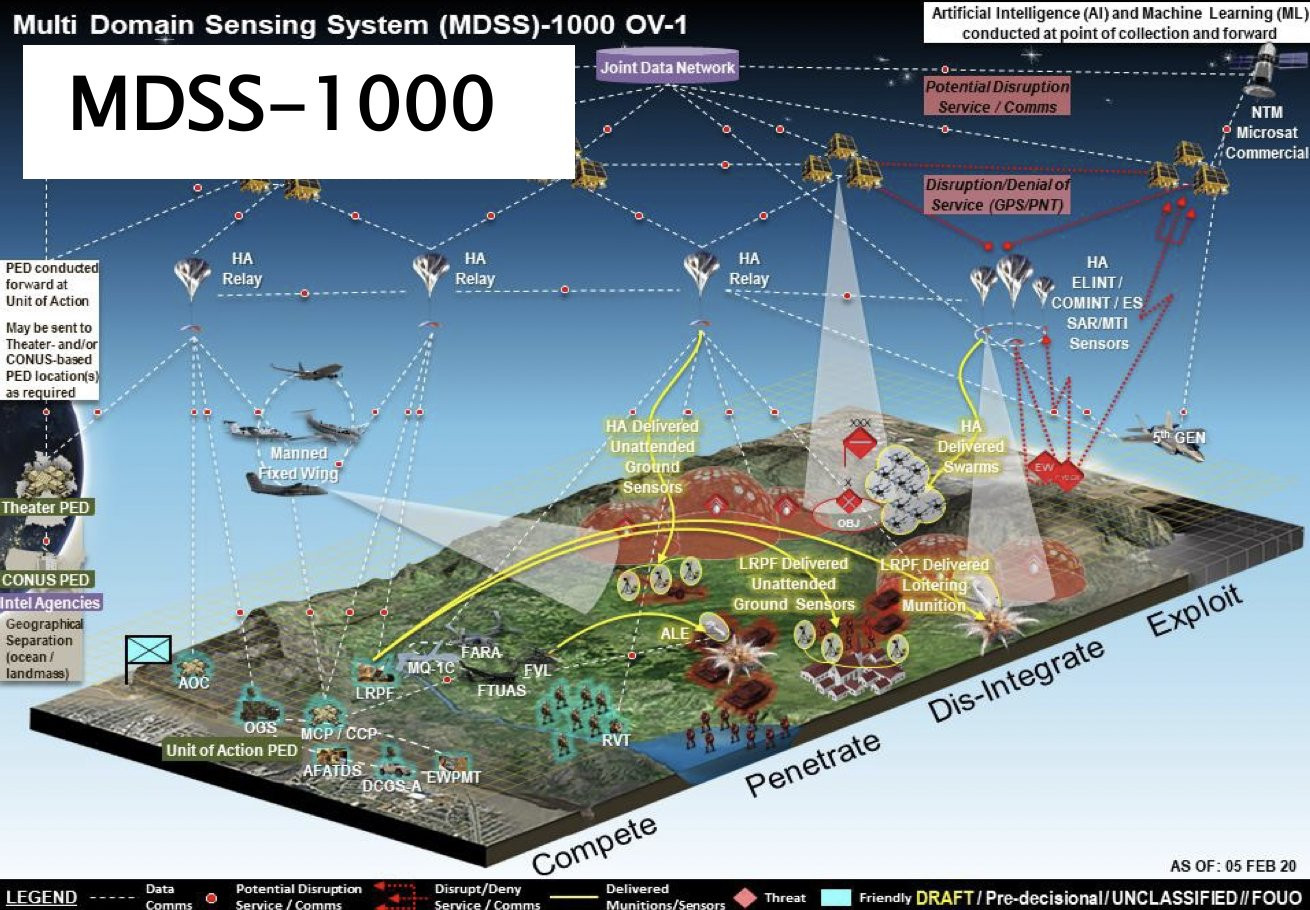

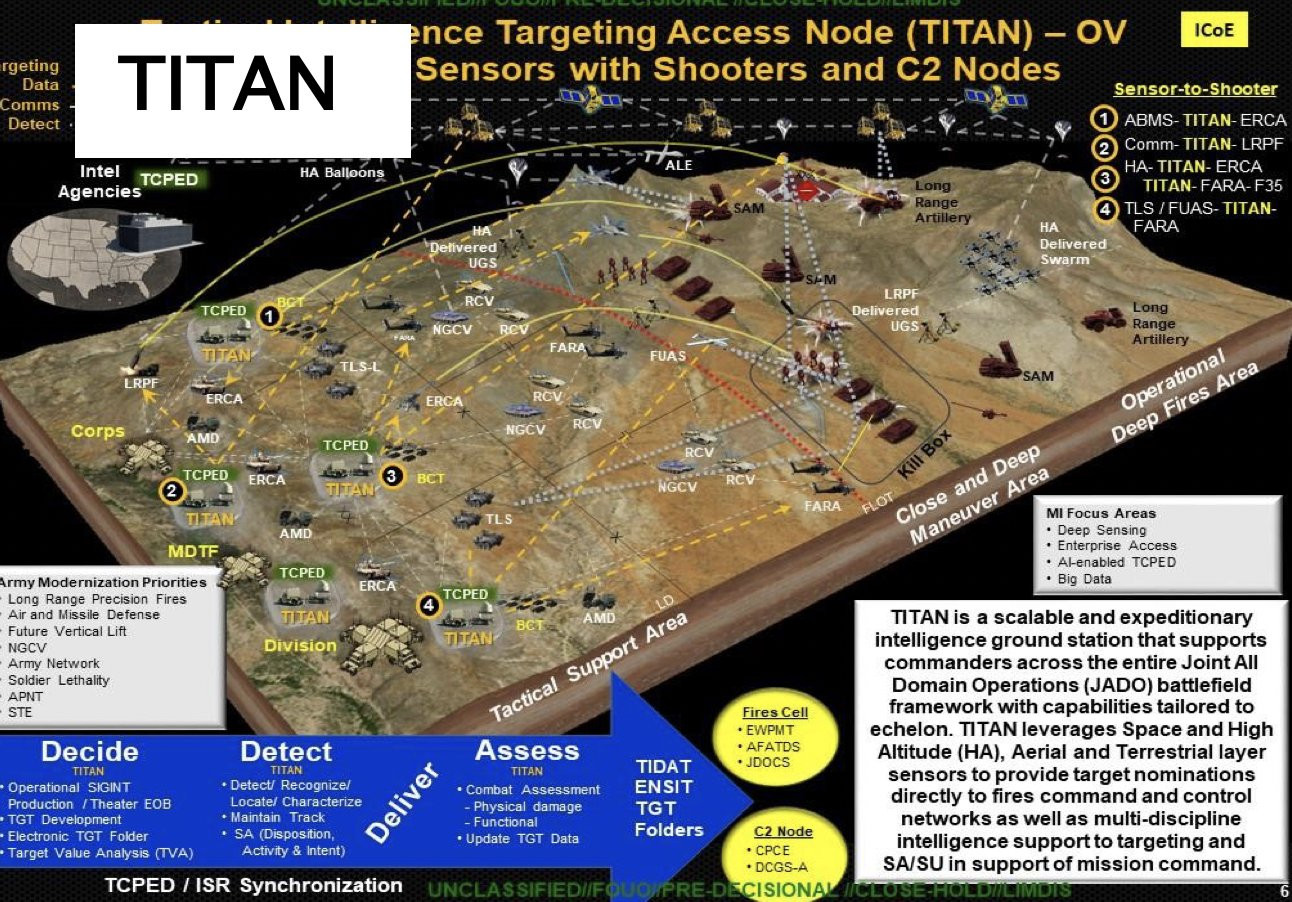

The Army’s Program Executive Office for Intelligence, Electronic Warfare, and Sensors, or PEO IEW&S, posted a briefing, which had been presented at a recent industry day event and that showed general depictions of these concepts of operation, on the U.S. government’s top contracting website, beta.SAMG.gov, last week. The balloons are one part of a broader, layered Multi-Domain Sensing System (MDSS) concept that the Army is in the early stages of developing.

Steve Trimble, Aviation Week‘s Defense Editor and good friend of The War Zone, managed to save a copy of the briefing, which was later taken down, and posted the slides on Twitter.

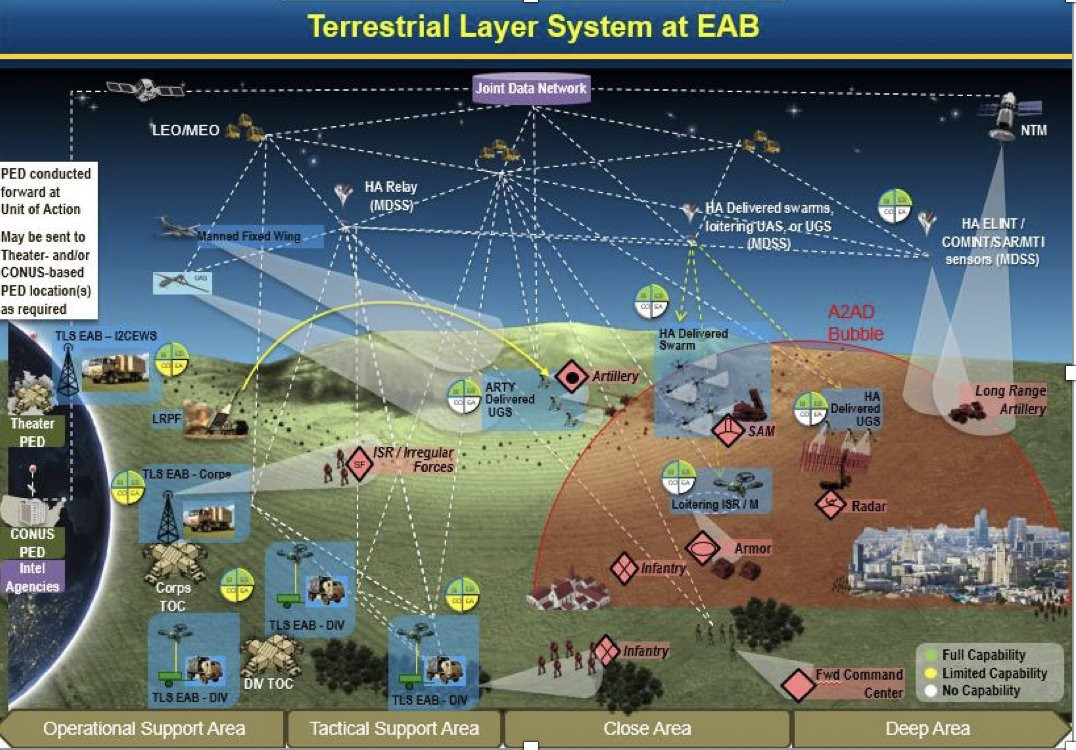

It was previously known that the Army was exploring using balloons floating in the stratosphere, which begins at altitudes ranging from 23,000 to 66,000 feet, depending on where you are on Earth, for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) and communications roles. As part of the larger MDSS network, they would fill something of a gap between traditional ground-based and aerial ISR and communications platforms and space-based systems.

“Conceptually, with the types of missions that the Multidomain Task Force is working, the high-altitude balloons would be a key capability enabler,” Brent Fraser, head of the Concept Development Division at Space and Missile Defense Center of Excellence, part of the Army’s Space and Missile Defense Command (SMDC), told Defense News in an interview in October. “[The balloons would] be able to provide some beyond-line-of-sight capability, whether it’s communications, extended distances, to be able to provide the ability to enable sensing of targets deep in the adversary’s areas, to be able to reinforce and complement existing sensing systems other than the aerial layer as well as the space layer.”

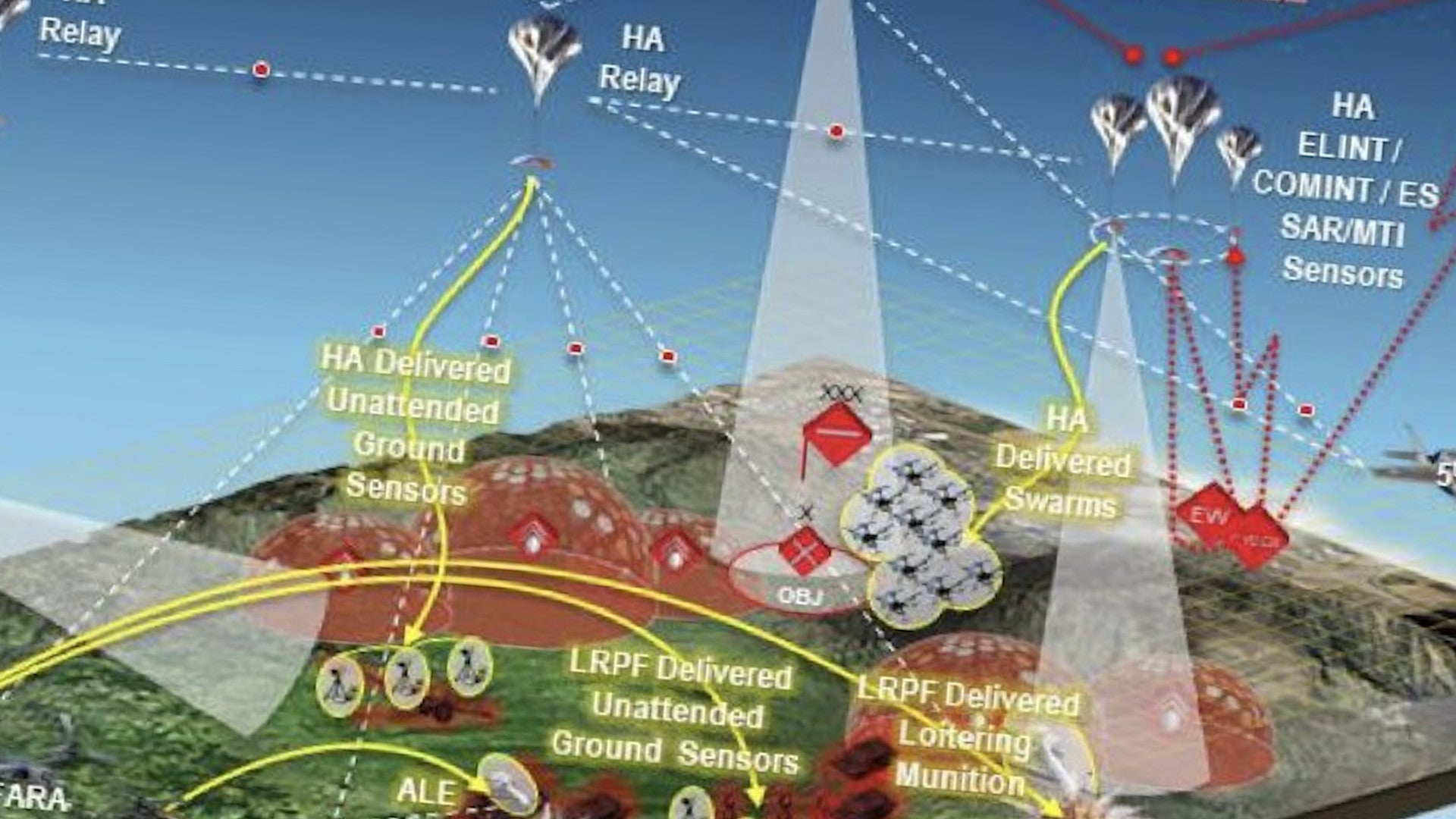

The PEO IEW&S slides, seen earlier in this story and below, show high-altitude (HA) balloons in these roles. When it comes to ISR, they indicate that the lighter-than-air craft could carry electronic intelligence (ELINT) and communications intelligence (COMINT) suites, as well as radars with synthetic aperture imaging, or SAR, and moving target indicator (MTI) functionality. Though not mentioned, these balloons would also be ideal platforms for carrying electronic warfare jammers and cyber warfare systems.

In addition, the slides also depict balloons sending out swarms of drones or deploying unattended ground sensors (UGS). No additional details are provided about the potential capabilities of the swarming drones of the UGSs.

It is worth noting that the Army is also in the process of developing air-launched drones, which could be fired from manned or unmanned aircraft, with swarming capabilities to carry out ISR missions and act as loitering munitions, as part of its Air Launch Effects (ALE) program. You can read more about that effort in this previous War Zone story.

The service is also exploring other novel loitering munition concepts, including potentially delivering them via a hypersonic missile as part of a program nicknamed Vintage Racer. The PEO IEW&S slides do notable depict units using missiles in development under the Army’s broad Long Range Precision Fires (LRPF) effort to deploy suicide drones, as well as clusters of UGSs, deep into enemy territory.

Using balloons for these various roles holds the promise of being able to deploy persistent capabilities in denied or semi-denied areas that could be difficult for an opponent to detect or neutralize. High-altitude balloons have traditionally had relatively small radar signatures and radar reflectors have been employed to make them more visible to reduce the chance of accidents. Electronic warfare packages, as well as using them tactically in concert with other platforms, could help maximize their survivability.

These would be cheaper than satellites and potentially less vulnerable than traditional manned or unmanned aircraft. With that in mind, balloons could also serve as at least interim replacements on relatively short notice for certain space-based capabilities, such as communications or navigation, should satellites get destroyed or otherwise disabled during a conflict, which is a very real possibility.

The ability to launch UGSs, or even carry out strikes directly on targets they find using individual loitering munitions or fully autonomous swarms, would only make them more flexible and disruptive to enemy operations. A swarm could include ISR-configured drones, as well as those capable of strikes, as well, allowing them to further scout ahead and find new targets on their own.

“It’s just phenomenal what we’re able to do with high-altitude balloons,” Army Lieutenant General Daniel Karbler told Defense News in an interview published earlier this month. “I don’t have the cost analysis but, in my mind, pennies on the dollar with respect to doing it. If I had to do it via a [low-Earth orbit] or some satellite constellation, what we are able to provide with high-altitude balloons, it’s tactically responsive support to the warfighter.”

Of course, this is hardly the first time that the Army, as well as the U.S. military, as a whole, has explored using lighter-than-air vehicles as sensor platforms or communications relays. The most infamous of these was the abortive Joint Land Attack Cruise Missile Defense Elevated Netted Sensor System, or JLENS, which were tethered aerostats carrying radars intended to spot and track incoming low-flying threats, including cruise missiles.

In 2015, a JLENS aerostat infamously broke free of its mooring at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland, drifted into neighboring Pennsylvania, and caused significant damage to power lines before becoming tangled in a tree. This incident, together with cost growth and delays, contributed to the decision to cancel that program in 2017. Other tethered aerostats carrying search radars, as well as electro-optical and infrared cameras, are still in use to provide surveillance around bases and support counter-drug operations in the Caribbean.

However, high-altitude balloons offer the ability to cover a much wider area than aerostats tethered to the ground, that are relegated to specific area surveillance. It’s not the first time that a military, as well as intelligence agencies, have used high-flying balloons for intelligence-gathering purposes, or even to launch attacks, either. During World War II, Japan launched balloons carrying incendiary bombs toward the Pacific Northwest with the hope of starting debilitating forest fires, a strategy that failed to produce any meaningful results. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), among others, employed balloons in the past to try to peer into denied areas, as well as to act as decoys part of a special project to gather information about Soviet radars, which you can read about more in this past War Zone piece.

Previously, these kinds of balloon-based systems had been limited in their utility because they were hard to control and could generally only stay aloft for periods measured in hours or days. Technological advancements mean that current generation high-altitude balloons are much easier to deliberately navigate to a desired area and can stay in the air for weeks or months at a time. In August, balloon-maker Raven Aerostar announced that one of its Thunderhead Balloon Systems had demonstrated its ability to stay aloft for 59 days.

The Army’s high-altitude balloon plans are not the only time in recent years that the U.S. military has explored the potential value of these lighter-than-air craft, as well. In 2019, U.S. Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) sponsored tests of Raven Aerostar balloons carrying ISR packages at altitudes of 65,000 feet across six states to explore their potential use in counter-drug operations and disaster response, as well as general intelligence collection.

The U.S. military isn’t the only one looking into uses for high-altitude balloons, either. Last week, NATO posted a video on YouTube about a project the alliance is conducting in cooperation with the University of New South Wales in Australia to develop a balloon-based radar system, ostensibly for “emergency response and disaster relief” scenarios.

Commercial companies have been looking into the use of high-altitude balloons, too. Loon, originally Project Loon, a subsidiary of Google parent company Alphabet, notably offers high-altitude balloons to help provide cell phone and internet service in remote areas or in the wake of a natural disaster.

The Army is still very much in the early stages of defining exactly what it might want from its balloon-based concepts of operation. “We’re in the initial stages of defining what those requirements would be,” Army Colonel Tim Dalton, a space and high altitude capability manager at SMDC’s Space and Missile Defense Center of Excellence, recently told Defense News. “There’s kind of two aspects to the high-altitude piece: the high-altitude platform, so it’s the balloon, and then whatever it’s carrying on there for a payload.”

From the briefing slides that have now emerged online, it seems clear that the Army is already looking at using high-altitude balloons in a number of different roles, including as platforms to deploy swarms to strike behind enemy lines.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com