One of the U.S. Navy’s dedicated adversary squadrons, VFC-12, the “Fighting Omars,” is about to get a massive increase in capability as it trades its “Legacy” F/A-18A+ and C/D model Hornets for early examples of the Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet. The War Zone can exclusively reveal that the squadron is expected to make the transition by October 2021. It marks the latest phase in the Navy’s divestment of original F/A-18A-D variants of the Hornet and the Fighting Omars will be the first Navy aggressor squadron to be fully equipped with the type.

The inclusion of early-batch Super Hornets in VFC-12’s adversary mission will alleviate the increasing burden of maintaining older Hornets, many of which have extremely high flight hours, plus it will add some notable enhancements to meet increasing demands for more robust ‘bandit’ threat training. It follows news that the U.S. Air Force is to similarly enhance its aggressor capabilities by using early examples of the F-35A and younger F-16C/Ds to equip the 65th Aggressor Squadron.

“We’re hoping that the daily availability of the Super Hornets will make it easier for everyone on the squadron to keep their flight hours up,” says VFC-12’s Lieutenant Commander Ian “Bro” Hutter. “The Super Hornet also carries more fuel, so it can stay airborne longer, which will also reduce the burden in terms of the actual number of sorties we have to fly,” he adds.

VFC-12, which is home-based at Naval Air Station Oceana in Virginia, and uses the radio callsign and nickname “Ambush,” looks set to receive some of the oldest Super Hornets previously in use by the fleet. These are examples that were originally assigned to Strike Fighter Squadron (VFA) 27 “Royal Maces” since 2004. This unit, assigned to Carrier Air Wing Five in Japan, swapped its original Block I F/A-18Es for new Block II examples.

Super Hornets will herald a welcome boost in the way the Fighting Omars fly their critical fleet support missions. It’s not currently clear if the jets destined for VFC-12 will be modified under the Boeing Service Life Modernization life extension program, which you can read more about here.

Transitioning VFC-12 to the Super Hornet is the latest in a succession of moves by the U.S. Navy to remove the 1980s-era Legacy Hornets from its inventory. It also reflects a need to evolve adversary technology and employ more advanced training techniques to meet growing threats abroad.

While the Marine Corps continues to operate the Hornet, original A-D models have all been retired from the front line Navy units, and the Blue Angels flight demonstration team is also now receiving Super Hornets, as well. Along with VFC-12, the “River Rattlers” of VFA-204, the U.S. Naval Test Pilot’s School (TPS), and the Naval Fighter Weapons School, better known as Topgun, are the only remaining Navy units that still fly the Legacy Hornet.

“Legacy” Hornet, modern mission

Lieutenant Commander Hutter spoke to The War Zone while deployed for a month with VFC-12 to Naval Air Station Key West, in Florida, supporting unit-level work-ups for fleet Super Hornet squadrons under the Strike Fighter Advanced Readiness Program, known as SFARP. One of the Fighting Omars’ main taskings is to provide high-end red air adversary threat presentations to fleet aviators in order to help them prepare for combat deployments.

“SFARP typically involves two fleet squadrons coming here for two weeks. They then leave and another two new squadrons rotate in here,” Hutter explains. SFARP is an initial phase in deployment work up preparations for Carrier Air Wing (CVW) strike fighter squadrons.

“If you break down our level of priorities at VFC-12, the highest would be what we call core events, which are related to the Optimized Fleet Response Plan [OFRP]. This starts about a year before a carrier air wing deploys. The first step of this is SFARP, which is squadron-level tactics, and is what we primarily support,” Hutter explains. “Squadrons typically conduct these events at Key West for air-to-air SFARP, and NAS Fallon for air-to-surface phases. VFC-12 provides threat aircraft presentations to give the fleet pilots a credible adversary to contend with during these periods.”

“We also support COMPTUEX [Composite Training Unit Exercises] in the latter part of the work-up, right as the units get ready to deploy on the carrier as an air wing. This typically means we deploy to NAS Jacksonville, Florida, for the East Coast, or to NAS North Island, California, for the West Coast. So we have four main detachment locations for us. SFARP and COMPTUEX trump everything else — if there’s a requirement for us to support either of those, we will drop everything and go.”

Next down the priority list is a relatively new mission known as Legacy Transition Training, or LTT. “We started this last year,” says Hutter, explaining how LTT is a training role the squadron picked up to convert existing aviators to fly the Legacy Hornet after the designated Fleet Replacement Squadron (FRS), VFA-106, the “Gladiators,” ceased flying training for Hornets in October 2019. VFC-12 now supports the pilot and maintainer training requirement to supply the handful of units in the Navy that still operate the F/A-18A-D.

“It’s going to be relatively short-lived, because we are scheduled to be transition-complete to the Super Hornet this time next year [November 2021],” says Hutter. “LTT is for staff instructors going to fly the C/D at Topgun, at VFA-204, or at TPS. We do their training and last year we had over 50 people come through for the five hours of flying training to get the ‘charlie qual.’”

The Omars also provide red air training for the Oceana-based units in what the squadron refers to as “fleet support” — but Hutter acknowledges this third tier responsibility is, unfortunately, on an as-available basis due to the myriad of more pressing demands.

Skilled hands

Like VFC-13, the “Fighting Saints,” at NAS Fallon, and VFC-111, the “Sundowners,” at NAS Key West, both of which fly the F-5N/F Tiger II, and aforementioned River Rattlers at Joint Reserve Base New Orleans, Louisiana, VFC-12 is part of the Tactical Support Wing (TSW), a wing belonging to the Naval Reserves. The U.S. Navy closed down its active-duty adversary squadrons in the mid-1990s, and in doing so (aside from Topgun instructors), it handed responsibility for red air over to the Reserves.

Hutter is the only Weapons Systems Officer (WSO) currently on staff at VFC-12 and, like most of the aircrew here, he is a highly experienced Topgun graduate. “Everyone here is technically a full-time reservist. Our current Skipper is full-time support staff, we also have four full-time support department heads. As far as pilots go, the rest are Selected Reservists [SELRES].” This means they have regular jobs away from the squadron, but provide a certain number of days per month. VFC-12’s maintainers are all U.S. Navy sailors, a mix of active-duty, full-time support, or the more traditional reservists, unlike the two F-5 squadrons, which have their maintenance undertaken by contractors.

“The great thing about VFC-12 is that we get to hand pick our staff for the most part. All our SELRES pilots are Topgun graduates with the blue patch. Probably 80% of our guys have gone through that syllabus and the experience here provides the ability to quickly transition between missions — to lead a flight at the last minute. Everyone in the squadron is of a very high caliber, and the importance of having that network of people, who can coordinate pretty much anything, cannot be overstated.”

The coveted blue patch is awarded to students who complete the main Topgun course, which is dedicated to friendly (Blue Air) tactics. Topgun also oversees a Navy adversary course that results in a graduate being awarded a red Topgun adversary patch. “In order to lead a core OFRP event, you have to be a Level 4 adversary,” explains Hutter. Individuals who graduate from the Topgun red air course are designated as a Level 5 adversary, the highest standard, and a training officer can then train Level 4 adversaries at the respective VFC units.

Hutter elaborates that Level 4 is essentially an adversary mission commander. “It means you can provide a high-quality threat representation and meet fighter training objectives in threat simulation. It also means that you are able to manage a lot of airplanes in the airspace.”

“VFC-12/13/111 and VFA-204 all send pilots through the red class at Topgun, then they come back to the squadron as training officers and qualify us. We have constant discussions with Topgun and we fight based on how they assess current threat capabilities. For VFC-12 specifically, our work is all about that high-end threat replication. When the fleet squadrons need a more benign ‘radar reflector’ for beyond visual range type engagements, they tend to use the F-5s. Those guys also support the FRS training units, but we typically don’t.”

“SFARP is managed by both the East and West Coast Strike Fighter Weapons Schools and it is designed to offer the most challenging division [4-ship] level fleet tactics. We’re doing that here at Key West right now; four blue air fleet Hornets against up to 20 bandits. There’s no contract red air at this SFARP, but it’s not unheard of for them to be here. As a squadron, we have 11 Hornets here now, and we are flying three ‘gos’ a day.”

VFC-12 offers the Navy’s highest level of threat replication, and it’s not just about a generic presentation. “We study threat pilot tactics and how threat nations operate,” says Hutter. “We understand how threat nations of interest operate, this isn’t red air between fellow JOs [Junior Officers]. Our threats are very specific. In SFARP it’s always Russian or Chinese aircraft. It’s not targeted at those countries, but they just have the most capable airplanes. So, it’s targeted at those top tier airframes.”

A changing mission

Describing a typical SFARP mission out of NAS Key West, Lieutenant Commander Hutter says: “You take off over the turquoise sea and fly over fishing boats, and do some cloud dodging. We fly in the Whiskey 174 range complex, which essentially runs between Key West and out towards Texas. The bandits flow out to the west, and the fighters start in the east. We need to get anywhere between 8 and 20 adversary aircraft together. Everyone checks in and we start our plan to confuse the fighters. The hardest part is keeping track of who is who.”

“We send a pilot to the TCTS [Tactical Combat Training System] range control center and they can work with the Range Training Officers on the radio to help ensure the objectives are met.” Hutter clarifies that the use of a Ground Controlled Intercept (GCI) controller very much depends on how much is going on. They are there to provide additional situational awareness on the evolving skirmish. “With the potential of over 20 fighters merging, the range/training safety officers are there to help avoid a collision. The VFC F-5s are now flying with Red Net. This works with the TCTS and, on an iPad in the cockpit, they can now see the whole air picture.” It’s a capability that VFC-12 expects to build upon when it receives its Super Hornets thanks to their Multifunction Information Distribution System (MIDS).”

“We use a standard height block structure [broken down within each 10,000ft block]. The blue air fighters are usually in the 5,000-9,000ft block and the bandits are 0-4,000ft. The higher and faster the shooters fly, the better the kinematics of the missiles. If we are up at 45,000ft and flying at Mach 1.2 indicated airspeed, we present a much harder problem for them. In the more complex exercises like Red Flag, you might hold for 30 minutes, fly towards the Blue guys, get told you’re dead, and never see another jet. The great thing about what we do in our division level tactics is that we can get a lot closer.”

“Merging and getting into a close turning fight very much depends on the mission that we are supporting. The fighters have some missions where their acceptable level of risk is low, so we, therefore, have very few merges. In fact, they will avoid the merge at all costs, preferring to run away. The higher their acceptable level of risk for the mission is, the more merges we will have. We’ll have flights where everybody merges! Typically that’s when there’s a lot of electronic attack out there, a lot of bandits and a lot of fighters. The higher the risk their mission is, the more willingness they have to go to the merge. Unless there are Raptors joining the fight. If Raptors are there, we never get to the merge,” smiles Hutter, emphasizing the U.S. Air Force fighter’s prowess in fighting at long range.

“Approaching the merge, if we don’t see the fighters then we will be at the bottom of our block height, and they will be at the top of theirs. That gives us a 1,000ft avoidance. If we see them, and we’re high on situational awareness, we can see everyone visually — all wingmen and tally all the fighters — then we are clear to come out of our block [and start Basic Fighter Maneuvers, BFM, aka dogfighting].” The contract red air providers are not permitted contractually to dogfight with fleet aircraft, and are often limited to level 180 degree turns. “The Navy contract for contract air support does not allow them to BFM,” Hutter confirms.

“Red air tactics are so advanced now. As a JO [junior officer] I remember the bandits flew slow, they stayed level, and maneuvered very little. Today, as red air, we are making sure we are as testing to the fighters as possible. It’s definitely not easy to do anymore. We are being asked to give the fighters increasingly robust presentations.”

New iron

As fleet units field increasing capabilities, the Navy adversaries are having to up their game. Currently, the use of simulation and synthetic training has not found its way into the VFC-12 world — it’s all about live flying. “Every day we see contractors working to make simulations better. Until it’s really good, seamless, we aren’t going to use it. In the workups towards SFARP, there is a simulator portion where we sit at the consoles and direct the red air simulation for the fighters. Until the synthetic training is seamless, it can be negative training or a waste of time if it’s not as good as the real thing.”

Hutter says VFC-12 has seen some change with the advent of the F-35 Lightning II, but mainly in the realm of security. “There are currently no separate training objectives for the F-35 than there are for the Super Hornet — we test them the same way, but that will change I’m sure. We are here to be threat representative and I don’t think any threat country knows how to truly deal with stealth technology yet, but it takes a long time for feedback to get to us.”

Having enjoyed a subtle upgrade by trading some of its F/A-18As for F/A-18C/Ds a couple of years ago as they were handed down from fleet units, Hutter says the move to the Super Hornet will have significant benefits.

The cost per flight hour of operating just a few units of C/D Hornets is significant, and the Navy wants to remove them from the inventory fast, consolidating on the Super Hornet. This means Topgun is likely to lose its handful of adversary Hornets flown by its instructors, meaning it might receive additional adversary “Rhinos.” In addition, the “River Rattlers” too are set to convert to a new type. Rumors have said this could see the VFA-204 receive secondhand F-16s, but nothing is publicly confirmed.

For VFC-12, its “new” jets will be pre-Lot 25 Block I standard Super Hornets. Examples from Lot 25 and beyond are Block II standard aircraft that use high-order language (HOL) software and are equipped with the AN/APG-79 Active Electronically Scanned Array (AESA) radar. F/A-18E/Fs prior to Lot 25 use “X-series” software, which mirrors that of the “Legacy” Hornet. Hutter explains that a Super Hornet fleet all equipped with the Block I’s AN/APG-73 mechanically scanned array radar and MIDS will be a huge advantage over the older Hornets. The current VFC-12 Hornets have a mix of AN/APG-65 and -73 radars.

“Some of our missions get really complicated, and in our current Hornets we might have low situational awareness. It’s not so much about being as lethal, here it’s also about herding a lot of cats,” says Hutter, who adds that it’s routine for Ambush aircrews to spend too much time being distracted by troubleshooting radar issues, and with no MIDS data link it makes the job of threat presentation work far more difficult while the pilots are busy trying to work out who is who, and where everyone is.

VFC-12 will not be the first to use the Super Hornet in the adversary role, with Topgun already operating a handful of early examples. VFC-12 should receive its first “Rhino” in February, with a dozen due to be on the flight line by October as it completes a staggered transition, which will enable it to continue its important mission in the meantime.

According to Hutter, the Super Hornets will give “Ambush” aircrews a better ability to detect targets at range, but also they will be harder to detect themselves, due to some of the low observable design features of the Super Hornet. “The Hornet is easier to ‘see’ than a Super Hornet,” he says. There are negatives though. “Seeing a different aircraft at the merge is helpful for fleet aviators. Most squadrons only ever see Super Hornets when they’re fighting.”

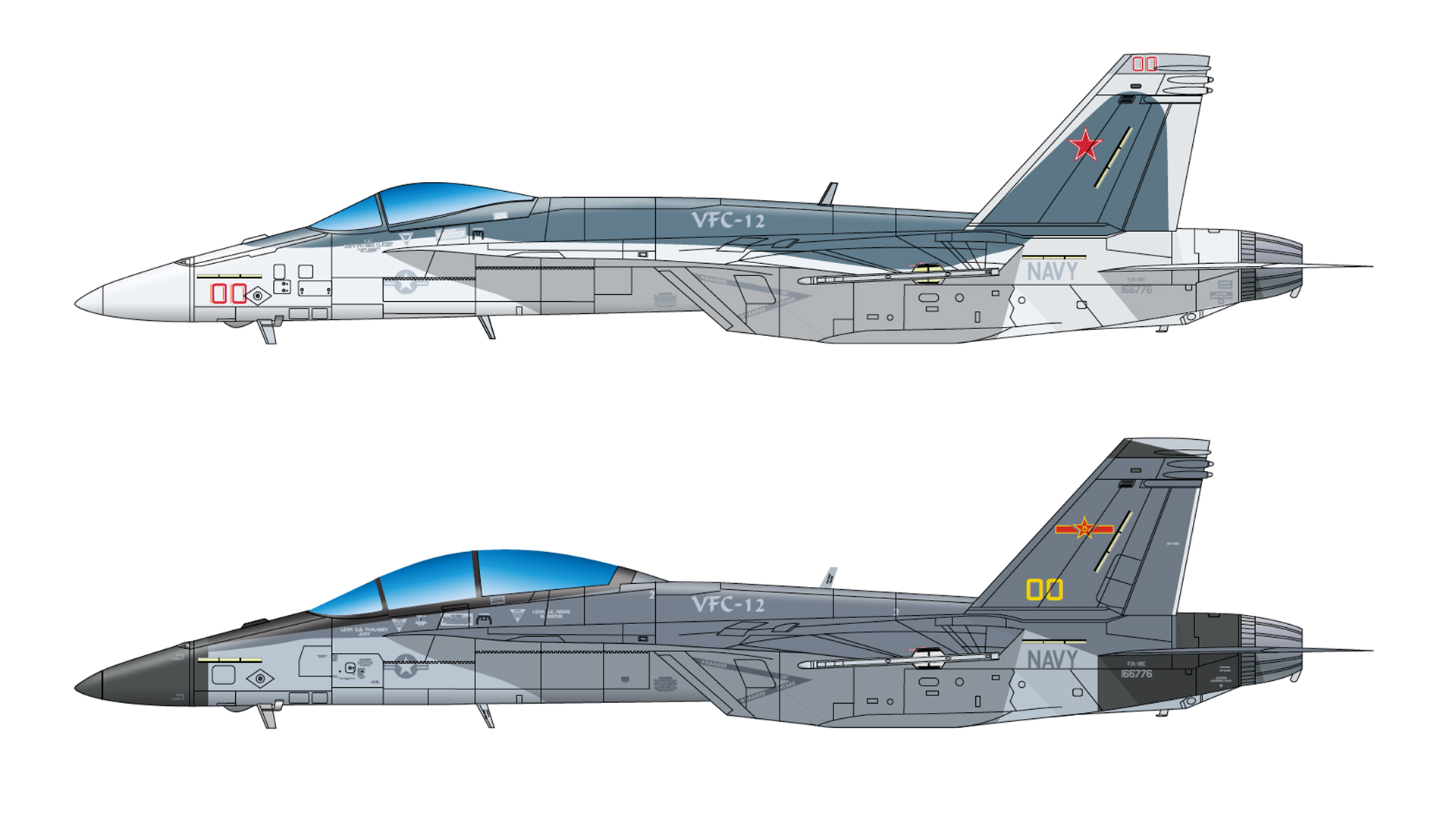

To make its Super Hornets look like realistic bandits, some remarkable special adversary schemes are being lined up for the new VFC-12 jets by Grant Little. Painting these aircraft differently compared to standard gray fleet jets will be more important than ever to help distinguish the bad guys. With a host of incredible suggested Russian and Chinese liveries on the drawing board, VFC-12 is well placed to retain its position flying some of the coolest-looking jets in the Navy, as well as upping its game to retain its standing as the Navy’s premier adversary squadron. We will be featuring a full set of the proposed VFC-12 Super Hornet schemes as a follow up to this exclusive story very soon.

Regardless of how they end up being painted, the Super Hornets will breathe new life into the Fighting Omars and will go a long way when it comes to keeping fleet pilots ready for any potential threats they could encounter while cruising some of the world’s tensest waters.

Editor’s note: Updated text to reflect that Grant Little was behind the new aggressor schemes that VFC-12 is applying to its jets. Hat tip to José “Fuji” Ramos for the heads up!

Contact the editor: Tyler@thedrive.com