Considering that the Junkers Ju 88 was the most versatile combat aircraft operated by Nazi Germany’s Luftwaffe in World War II, it is somewhat surprising that only two fully intact examples survived the conflict and can be seen today. One of those aircraft is the sole reconnaissance version of the Ju 88 that made it out of the war unscathed — and the story of how, aided in part by a Romanian defector, Nicolae Teodoru, it eventually made it to the United States, is a remarkable one.

Teodoru, then a Sergeant in the Romanian Air Force, brought the German-made Ju-88D-1, construction number 430650, to Limassol airfield in July 1943. At the time, Romania was an ally of Nazi Germany and had acquired various combat aircraft and other weaponry from that country.

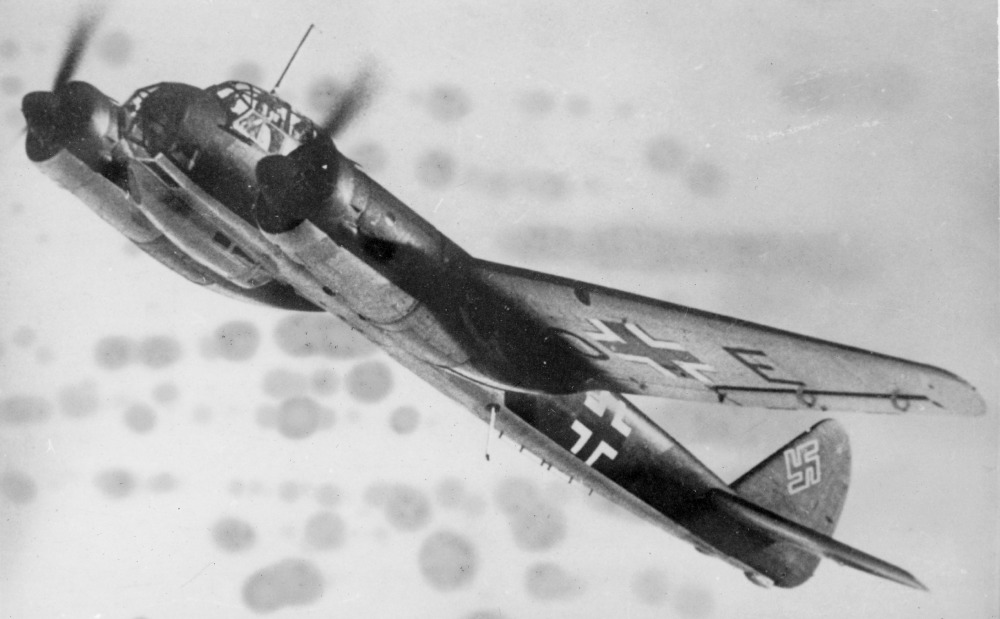

By that point, the Ju 88 had been a key component of the Luftwaffe’s combat fleets for years and, despite originally being designed as a bomber, proved readily adaptable to a host of other missions. Different records state that between 14,500 and 15,000 Ju 88s, in total, were churned out by different factories between 1939 and 1945, in as many as 60 different variants and sub-variants. The twin-engine type served in almost every conceivable role: bomber, heavy fighter, reconnaissance aircraft, night-fighter, anti-tank aircraft, anti-shipping aircraft, unpiloted missile, and more.

The Ju 88D-1 was a long-range reconnaissance aircraft, powered by a pair of Junkers Jumo 211J inverted V12 engines, providing 2,400 horsepower between them. The aircraft had a maximum speed of around 295 miles per hour and a range of over 1,500 miles. The D-1 had a normal crew of four and defensive armament of three MG 15 machine guns of 7.92-millimeter caliber.

The D-1 had first entered Luftwaffe service in the summer of 1940, but was also widely exported to Nazi allies, along with other variants. Ju 88s of various types also flew in the hands of Croatia, Finland, Hungary, and Italy.

At the time of Teodoru’s defection, Romania had only been operating the type for a matter of months. The country received its first batch of 50 Ju 88s, including a dozen Ju 88D-1s, in the first half of 1943, and their crews were trained in Ukraine, by Luftwaffe instructors. These aircraft were part of a larger effort by the Nazis to build up the air force of its Axis partner, which was also fighting against the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front.

The Ju 88D-1s were assigned to the Romanian Air Force’s 2nd Reconnaissance Squadron, based at Mariupol, in southeastern Ukraine. Sergeant Teodoru, a civil pilot who had been called up for duty at age 28, was among the personnel assigned to that unit.

Between June and July 1943, he flew 11 missions over the Eastern Front, without incident. He was, however, less than happy with military service and hatched a plan to defect to the Allies. In the words of Romanian aviation historian Danut Vlad, Teodoru was “unable to accept military discipline.”

Teodoru planned an escape in one of the Ju-88s, which would involve him crossing the Sea of Azov via Novorossiysk, on Russia’s Black Sea coast, to Aleppo in Syria. There, he would refuel before taking off for the final leg of his mission, to Beirut in Lebanon, which was then a major Allied base for its naval operations in the Mediterranean.

The Romanian sergeant set out on the afternoon of July 22, 1943, taking off from Mariupol, a major city in what then Germany-occupied Soviet Ukraine, in Ju 88D-1 430650. He was alone in the cockpit and carried no maps so that his plan would not be revealed if he were to be shot down or crash.

Things were proceeding smoothly until Teodoru made his way over Novorossiysk, after which a strong easterly wind over the Black Sea began to blow him off course, towards Turkey. He eventually arrived in that country’s airspace somewhere near Anamur on the coast of the Black Sea. Whether aware or not of the error, he continued to fly over Turkish territory and then entered the Mediterranean, on a course headed for Cyprus, which was home to an important Allied air base.

Four British Royal Air Force Hawker Hurricane IIB fighters were duly scrambled from their base at Nicosia in Cyprus once Teodoru’s Junkers arrived over the island. The Romanian clearly managed to signal to the RAF pilots that he intended to land and was not on a combat mission. They escorted him down to a landing at Limassol airfield, where he touched down in the early evening.

After landing, Teodoru reportedly handed his aircraft over to his RAF hosts, declaring that it was a “gift from the Führer.”

The Ju 88D-1 was a very useful intelligence windfall for the British and, with only 50 flying hours, was ideal for extensive evaluation. Duly repainted in RAF colors and markings, the Ju 88 was moved to Heliopolis near Cairo in Egypt for flight testing. Here, a series of trials were undertaken under the command of test pilot Wing Commander Charles Sandford Wynne-Eyton.

What became of Nicolae Teodoru is unclear, but an individual with this name appears again in a CIA report on the post-war Romanian Air Force, dated April 1953. This document identifies the individual in question as commander of the 6th Bomber Regiment at Brasov Airfield, as of 1949, and that the unit was established with pilots who had “multiple-engine experience.” This could suggest that Teodoru eventually made his way back to Romania and continued his career in the Communist-era air force.

As for the Ju 88D-1 he had defected in, after concluding its test campaign, the British decided to transfer it to the United States. Earlier that summer, the United Kingdom had acquired a more advanced variant, a Ju 88R-1 night-fighter, which had landed in Scotland as the result of another defection from within the Luftwaffe.

After providing the United Kingdom with first-hand experience of the performance and capabilities of one of its enemy’s key aircraft, the Ju 88D-1 would now provide similar insight for the U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF), which was also engaged against Axis forces in North Africa, Italy, and Western Europe.

In October 1943, a USAAF crew flew the Ju 88D-1 from Heliopolis to Deversoir Air Base, near Cairo, where they then became familiarized with the aircraft, with the aim of flying it to the United States where it could be more extensively assessed. Heading up the USAAF team was then-Captain Warner E. Newby, who already had useful experience on the B-25 Mitchell, a comparable American twin-engine bomber.

The Junkers required considerable modifications for its multi-leg flight to the United States, including additional external fuel tanks that were obtained from a crashed USAAF P-38 Lightning fighter, rigged up to the fuel system using pumps “borrowed” from a B-24 Liberator bomber. Meanwhile, instead of German fuel, oil, and coolant, the team used U.S.-specification equivalents.

The aircraft’s machine guns and cameras were removed and an ARN-7 direction-finder added to help with long-range navigation over the route. The conversion work and subsequent flight testing were far from straightforward and on one occasion an external fuel tank was accidentally jettisoned and exploded, showering the aircraft with shrapnel and injuring several crew members.

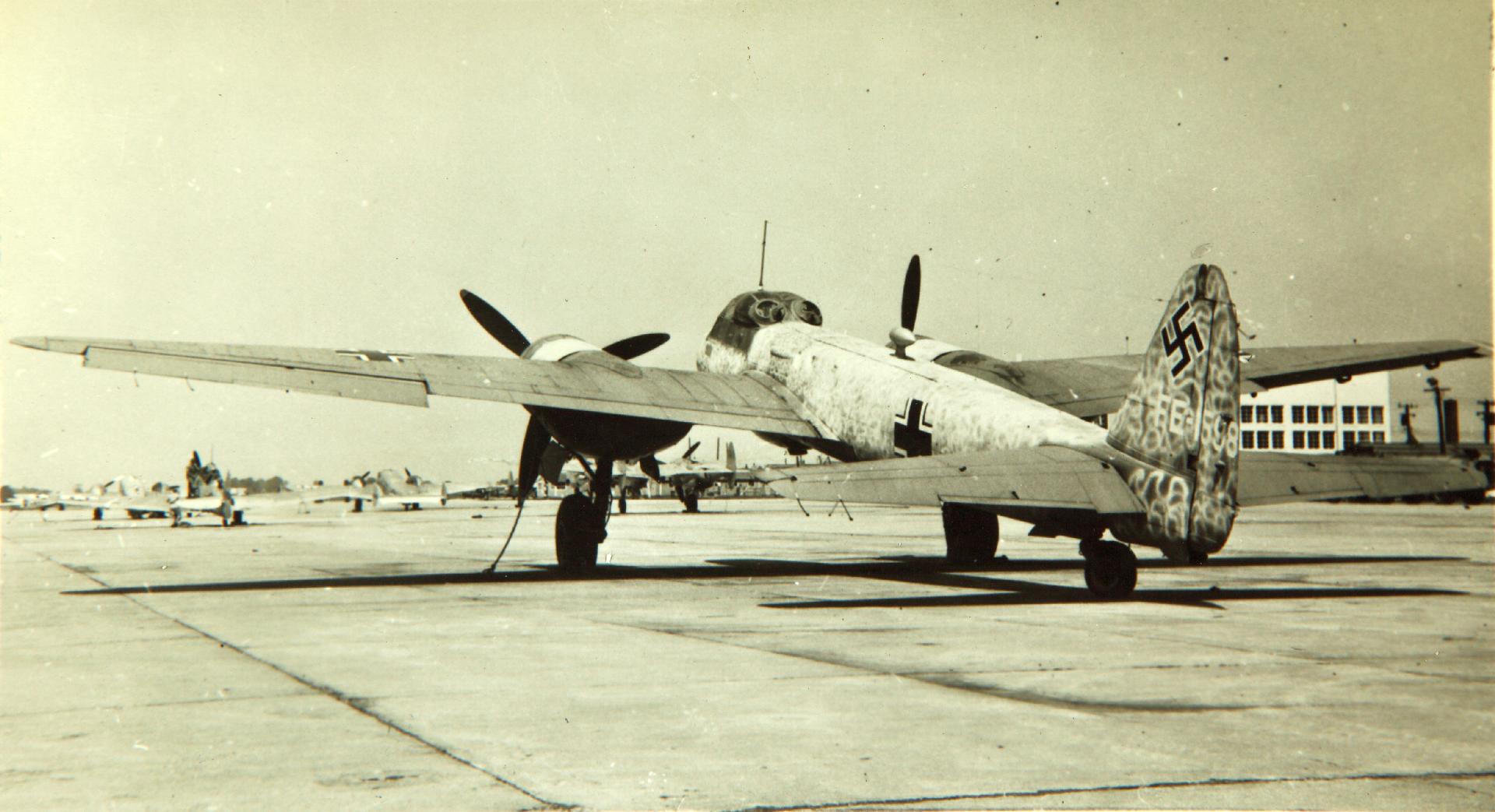

Now nicknamed “Baksheesh,” an Arabic word meaning a charitable monetary gift, the aircraft received its final preparations for the flight to its new home: extra-large USAAF markings, American flags on the wings, and, reportedly, a golden band around the rear fuselage.

With Captain Newby again heading up the crew, the flight to the United States began on October 8, 1943, and the distance of 10,400 nautical miles was completed in seven days. Refueling and crew rest stops were made in Sudan, Nigeria, the Gold Coast (today, Ghana), the United Kingdom’s Ascension Island in the Atlantic Ocean, Brazil (two stops), British Guyana, Puerto Rico, and West Palm Beach in Florida.

There were a few problems en route, including a lack of the correct fuel on Ascension Island. The crew was forced to use the wrong fuel type, risking potential engine failure. During one of the landings in Brazil, the aircraft’s landing gear also failed to deploy properly, forcing the crew to resort to emergency manual override.

Finally, on October 14, the Baksheesh touched down at Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio, and began its test career with the Flight Test Engineering Division. It was test-flown there between November 1943 and March 1944, before going to Arizona for yet more trials.

The huge effort required to bring the Ju 88 to Dayton shows the lengths to which the United States was willing to go to get its hands on foreign aircraft equipment for analysis and evaluation, what is known today as foreign materiel exploitation (FME). During the Cold War, these efforts would result in an ex-Iraqi Air Force MiG-21 being loaned from Israel and tested over Groom Lake, Nevada, before the 4477th Test and Evaluation Squadron “Red Eagles” conducted highly classified missions with a fleet of Soviet-bloc jet fighters operated from the secluded Tonopah Test Range (TTR).

However, by 1946, the Ju 88D-1 had ceased to be of use, and it was decided to store it at Davis-Monthan Field (later Davis-Monthan Air Force Base) in Arizona, which, today, is home to the Air Force’s famed aircraft storage boneyard. In the meantime, the United States had acquired at least five other Ju 88s, but it was the Baksheesh that was destined to be preserved. In 1950, it was transferred to what was then the Air Force Technical Museum, in whose hands it remains today.

Despite the enormous production total, only two Ju 88 ultimately survived the war in complete condition, as opposed to having been recovered from crash sites or pieced together using surviving parts from more than one aircraft. One of those is 430650, the only remaining D variant and the only World War II-era Romanian Air Force combat aircraft in a museum collection anywhere in the world.

Teodoru’s Ju 88D-1 is preserved today at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, adjacent to what is now Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton. It stands testament to a unique intertwined wartime story, one that took it, and those who flew it, from Ukraine to North Africa, via the Mediterranean, and then finally on to the United States.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com