The U.S. Army has released what appears to be one of the first images of a prototype low-cost surface-to-air missile following a successful flight test. The weapon is primarily designed to provide a defense against unmanned aerial vehicles and cruise missiles, but could also engage fixed and rotary wing aircraft in certain envelopes. It is intended to be cheaper to employ than the Patriot surface-to-air missile system, but has a greater range and is otherwise far more capable than the shoulder-fired Stinger man-portable air defense system, or MANPADS.

The Army’s Combat Capabilities Development Command’s (CCDC) Aviation and Missile Center announced the successful flight test on Twitter on Nov. 9, 2020. The social media post did not say when or where the service had fired the missile or offer any additional details about the test parameters.

This is not the first flight test of this missile under what is formally known as the Low-Cost Extended Range Air Defense (LOWER-AD) program. However, the accompanying picture the Army released, seen at the top of this story and below, showed a yellow band on the forward portion of the missile body, which typically indicates the presence of a live high-explosive warhead, as well as a brown one at the center, generally used to mark the location of a missile’s rocket motor. All this suggests that this may have been one of the first tests of a fully-functional prototype against an actual target of some kind.

“LOWER AD will conduct a flight test in fiscal year 2021, using various targets at extended ranges to demonstrate Level 6 maturity of the technology,” CCDC had said in September 2019. The 2021 Fiscal Year began on Oct. 1.

The Army’s most recent budget request for the 2021 Fiscal Year had also said that its plans for the previous fiscal cycle had included integrating the “motor, airframe, mission computer, power supply, telemetry, and data link as an interceptor for demonstrating initial capability in two Ballistic Test Vehicle (BTV) flight tests.” There is notably no mention of a warhead with regards to those flight tests.

It’s also not clear who the U.S. Army is working with on the development of the missile. It does have some visual similarities to concept art Raytheon has previously released of its Peregine, a small air-to-air missile derived from the AIM-120 Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile (AMRAAM), but we no indication that there is a relationship of any kind between the two weapons.

We do know that the service has conducted other flight testing in support of the LOWER-AD program since at least 2018, when it carried out “successful Launch Test Vehicle flight tests to verify operation of the launcher testbed and validate predictive dynamic models,” according to one CCDC document. The program, as a whole, has been ongoing since at least 2012.

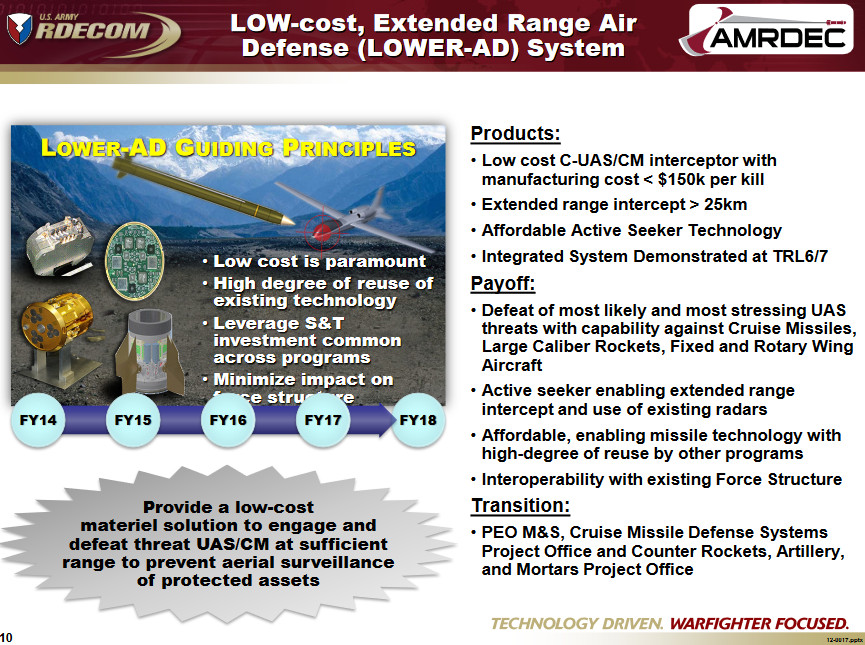

The stated goal at that time was to develop an air defense interceptor that would have a range of more than 25 kilometers, or over 15.5 miles, and be able to knock down fixed and rotary wing aircraft and large artillery rockets, as well as drones and cruise missiles. The missile would be cued using existing Army radars and use an active seeker of an unspecified type to home in on its target in the terminal phase of flight.

The hope was that the weapon would be able to do this all while costing less than $150,000 “per kill.” It’s not clear what the current projected unit cost of the LOWER-AD interceptor is, but, for comparison, the Army said it expected to pay just over $3.85 million for each of 122 examples of the latest PAC-3 Missile Segment Enhancement (MSE) interceptors for its Patriot systems in its 2021 Fiscal Year budget request.

Various interceptors for Patriot have demonstrated their ability to knock down targets representing subsonic cruise missiles and lower-end unmanned aerial vehicles, but at a significant expense compared to that of the incoming threat. “That quadcopter that cost 200 bucks from Amazon.com did not stand a chance against a Patriot,” now-retired Army General David G. Perkins, then commander of the Army’s Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), said during a speech in 2017, underscoring the cost disparity. Perkins was referring to a then-recent intercept that an unspecified “ally,” possibly Israel, had carried out using that surface-to-air missile system.

The concern has long been that during an actual conflict, it could become exorbitantly expensive for the Army to intercept waves of incoming cruise missiles or swarms of unmanned aircraft using Patriot alone. Smaller, cheaper interceptors, such as LOWER-AD, could also offer Army units valuable additional magazine depth when dealing with large groups of threats.

“The LOWER AD technology will make it possible to reduce the size of the missile, which in turn will allow more missiles per launcher,” the Army said in 2019. “Internal components of the LOWER AD missile technology will include improved navigation and a low-cost seeker and warhead, which will maximize its capability to protect defended areas and troops.”

LOWER-AD is just one of a multitude of efforts the Army, along with the other branches of the U.S. military, is working on now, including using 155mm self-propelled howitzers to shoot down cruise missiles, to make up for the fact that shorter-range and lower-tier air defense capabilities quickly atrophied across all of the services after the end of the Cold War. You can read about these somewhat dire circumstances in more detail in this past War Zone piece. This has come as the U.S. military, as a whole, has sought to reorient itself to be more prepared for potential high-end conflicts against major adversaries, such as Russia and China, who are developing increasingly more capable drone and cruise missile technology.

Of course, small drones and lower-end cruise missiles are also increasingly proliferating to smaller countries and even non-state actors. All this has underscored the threat these weapons pose to American troops on the battlefield, as well as in garrison, especially at bases overseas, not to mention to other sensitive targets outside of a conventional conflict. These are issues that the War Zone

has been exploring and highlighting for years now.

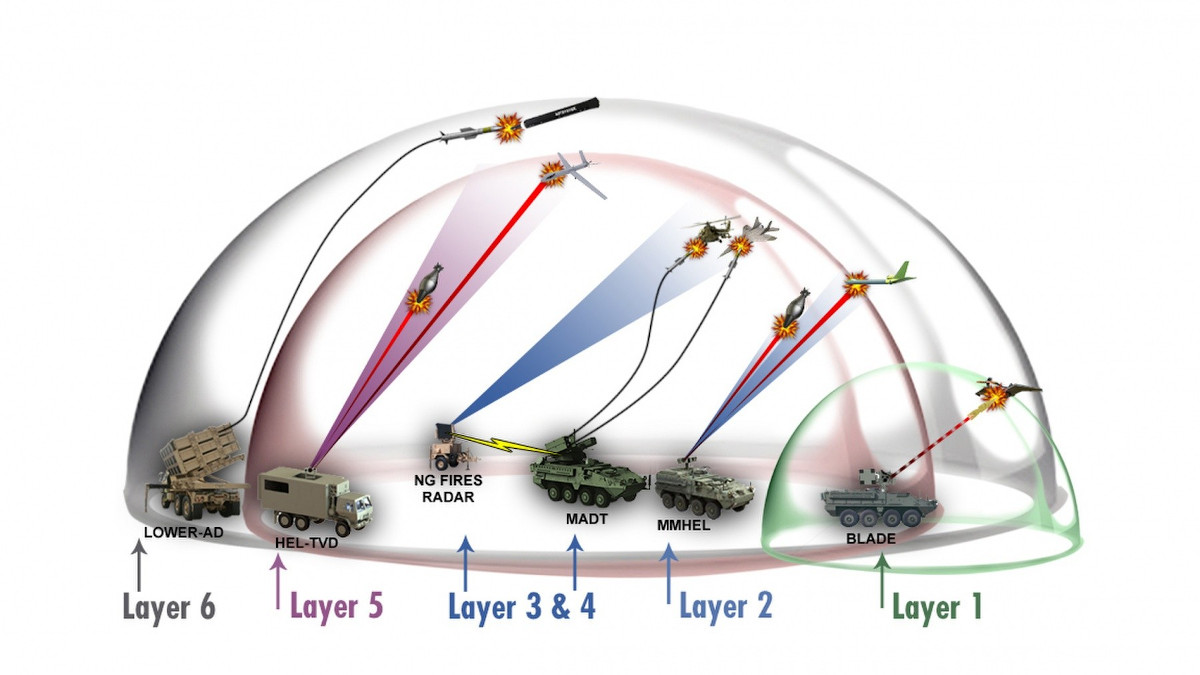

LOWER-AD is also set to form the top end of a future Army layered shorter-range air defense architecture that also includes a number of other gun, missile, and directed energy-based systems meant to counter a variety of threats, ranging from fixed and rotary wing aircraft to artillery rockets, shells, and mortar bombs. The latter mission set is typically referred to as Counter Rockets, Artillery, and Mortars, or C-RAM. The service’s primary C-RAM system at present is Centurian, a ground-based version of the U.S. Navy’s Phalanx Close-In Weapon System (CIWS), which features a 20mm Vulcan cannon.

In October, the Army also received the first of two batteries worth of the Israeli-made Iron Dome system, which is primarily geared toward the C-RAM mission. However, the service had initially decided to acquire these systems primarily to satisfy interim cruise missile defense requirements. This demand had become more pronounced with its separate decision to cancel work on its Multi-Mission Launcher (MML) system, a truck-mounted system that was to be capable of firing various kinds of air and missile defense interceptors to respond to a variety of threats.

However, the Army subsequently halted those plans over concerns about whether Iron Dome could adequately defend against these threats, as well as issues relating to integrating the systems with its over-arching Integrated Battle Command System (IBCS) network architecture, which you can read about in more detail in this recent War Zone feature. It’s unclear how the two batteries it has already agreed to buy will now be integrated into the service’s overall air and missile defense force structure plans.

On top of all that, the Army recently announced plans to acquire a ground-launched version of the U.S. Navy’s SM-6 missile, ostensibly as a medium-range surface-to-surface weapon. However, the existing variants of this missile have air and missile defense capabilities, as well, which might lead to their future inclusion into its integrated air defense plans.

LOWER-AD, and the recent successful test of a prototype interceptor, represents another important push to develop a low-cost air and missile defense interceptor that could fill a critical gap between Patriot and lower-end short-range air defense systems.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com