Recently, a very unique and heavily modified Boeing 707 aircraft arrived at the U.S. Air Force’s famous boneyard at Davis Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona. For nearly three decades, Lincoln Laboratory had operated this aircraft, most recently nicknamed Shashambre, as a flying testbed for various advanced sensors, electronics, and more, as part of a collaborative effort with the Air Force.

Shashambre touched down at the boneyard on Oct. 26, 2020. The Lincoln Laboratory, a Department of Defense-funded research and development center housed within the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and first founded in 1951, had previously announced that the aircraft, which also carried the U.S. civil registration code N404PA and has been referred to in the past as the Lincoln Multifunction Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance Testbed, or LiMIT, had flown its last test mission on Sept. 15.

The War Zone has now obtained pictures, seen at the top of this story and below, of the aircraft as it appears now at Davis Monthan AFB. One of the jet’s two distinctive cheek fairings, which could hold radars, as well as other sensors and payloads during testing, is still prominently visible in the photos.

However, a large dorsal hump at the rear of the fuselage, typically associated with wideband satellite communications systems, and a smaller dome on top of the fuselage above the cockpit, as seen in the videos below, which had been fitted the aircraft on and off since at least 2009, are now missing.

Multiple platter-type antennas that had been fitted on various occasions to each side of the center of the fuselage, and which are also commonly associated with ultra-high-frequency satellite communications systems, have notably been removed, as well. The aircraft does still has various other smaller antennas on top of and below its fuselage, as well as one on the tip of its tail.

The Lincoln Laboratory first acquired this aircraft in 1988, in order to support a specific program “that explored electromagnetic influences” on electronics, according to an official news item about Shashambre’s retirement. “The Boeing 707 platform was chosen because of its size, availability, low purchase cost, and the extensive experience on the part of the Air Force and others in modifying the airframe,” according to a separate Lincoln Laboratory document.

The laboratory subsequently found a suitable example in a Florida boneyard, where it had been sitting in storage for some time. The jet in question had first rolled off Boeing’s line in 1965 and was among the first batch of 707s to be powered by Pratt & Whitney JT-3D turbofan engines, also known as the TF-33. This is the same engine still found on the Air Force’s B-52 bombers and also powered various variants of that service’s C-135 family, including certain KC-135 tankers and RC-135 spy planes.

It initially entered service with Pan American airlines with the name Clipper Seven Seas. Before its retirement from airline duties, “the aircraft had been leased by several regional carriers, shuttling college students to Daytona Beach for spring break, among other duties,” according to the Lincoln Laboratory.

“There are lots of stories about the overhaul process: we discovered cracks in the wing spars that needed repair; the engines were from an airline in China, so all the service data and manuals were in Chinese, forcing us to strip the engines down and essentially ‘zero time’ them [start from scratch],” David Kettner, who headed up the program the aircraft was initially purchased to support, said in the Lincoln Laboratory’s piece on its recent retirement. “I sometimes wondered if we were ever going to get all the work done.”

The jet eventually made its way to E-Systems in Greenville, Texas, a firm well-known for its involvement in various Air Force intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) projects and other specialized aircraft modification and conversion programs dating back to the 1960s. E-Systems has changed hands multiple times since then and is now a division of L3Harris.

The final converted 707 finally arrived at Hanscom Air Force Base in Massachusetts in 1991. The Lincoln Laboratory had established a small flight test center at the base, which remains there to this day, and at the time, it was also home to the Electronic Systems Division of Air Force Systems Command. The following year, that unit was redesignated as the Electronic Systems Center and became part of the restructured Air Force Materiel Command (AFMC).

The jet, originally nicknamed Paul Revere, after the famous Revolutionary War patriot and Massachusetts icon, continued to support the electromagnetic research effort until 1999. After that program ended, the Lincoln Laboratory decided to continue operating the jet together with the Air Force to support various other test programs. Over the years, a number of additional improvements and modifications to the aircraft were made.

“An extensive fiber-optic network backbone was installed along with two workstation tables, each capable of hosting six operators with computer access to the network,” according to the Lincoln Laboratory. “The power system was upgraded, several additional radomes were installed to handle communications antennas, and a liquid-cooling system was installed to cool power-hungry electronics.”

The aircraft, which subsequently received the nicknames and Hannah and then Shashambre, the exact origins of which are unclear, also got upgrades focused on giving it an increasingly more modular, plug-and-play architecture to allow for different test payloads to be more rapidly installed and removed. “We like to think of this flying laboratory as a Mr. Potato Head,” Dr. Joe Chapa, a Lincoln Laboratory researcher, said in 2004. “We can put a different nose or a different eye on.”

All told, “N404PA has capabilities not available in other test aircraft, which allow the laboratory to rapidly prototype and demonstrate solutions to the hard communication and ISR challenges facing the nation,” Stephen McGarry, a member of the laboratory’s senior staff and former assistant leader of its Tactical Networks Group, said in the official story on the aircraft’s retirement.

A full list of the projects the former airliner took part in is unknown and many likely remain classified. “In 2001, the aircraft was assigned to an Air Force–sponsored program that was developing and demonstrating an intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) platform that would be interoperable with other aircraft,” which “contributed to the modernization of military airborne command and control flight platforms that are still in use today,” according to the Lincoln Laboratory.

In 2002, it supported work “to develop and demonstrate a next-generation multi-sensor command and control airborne test platform.” It’s not clear what that program might have been, but the following year, a team consisting of Northrop Grumman, Boeing, and Raytheon received a contract from the Air Force to begin development of what would become known as the E-10A Multi-Sensor Command and Control Aircraft (MC2A), which was to be based on the Boeing 767-400ER.

This was an ambitious effort meant to eventually replace the service’s E-3 Sentry Airborne Warning And Control System (AWACS) radar planes and E-8C Joint Surveillance Target Attack Radar System (JSTARS) battle management aircraft, as well as its E-4B Nightwatch “doomsday” command and control jets and RC-135V/W Rivet Joint spy planes. In 2007, the Air Force canceled the project. Boeing sold the E-10A prototype to Bahrain, after which it was converted into a VIP aircraft.

In the early 2000s, N404PA supported a program to test new software algorithms designed to improve Ground Moving Target Indicator (GMTI) and Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) data processing in support of Discoverer II space-based radar program, a program the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) conducted together with the Air Force and the secretive National Reconnaissance Office (NRO). “GMTI from space brought on challenges beyond those for airborne systems because of the very high velocities of satellites (approximately 40 times that of airplanes),” according to one Lincoln Laboratory document.

“The Laboratory developed and optimized the performance of a set of space-time adaptive processing (STAP) algorithms specifically for space radar,” it continued. “However, without a space-based radar, it was difficult to carry out two key steps in the Laboratory development approach: field testing and demonstration of operational utility.”

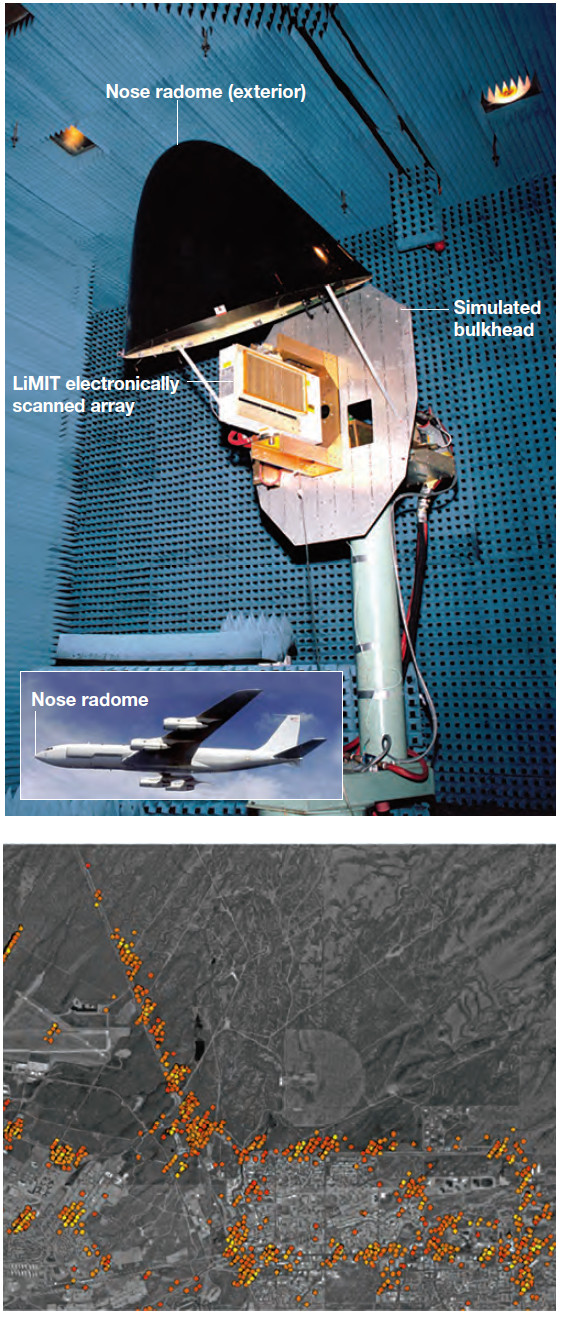

Lincoln Laboratory personnel subsequently installed a “scaled system [that] consists of a small multichannel antenna, similar to the antenna architecture for the space radar” in the nose of their modified 707. ” In this role, LiMIT has participated in a number of enterprise-level field exercises to demonstrate the ISR potential of space-based radar.”

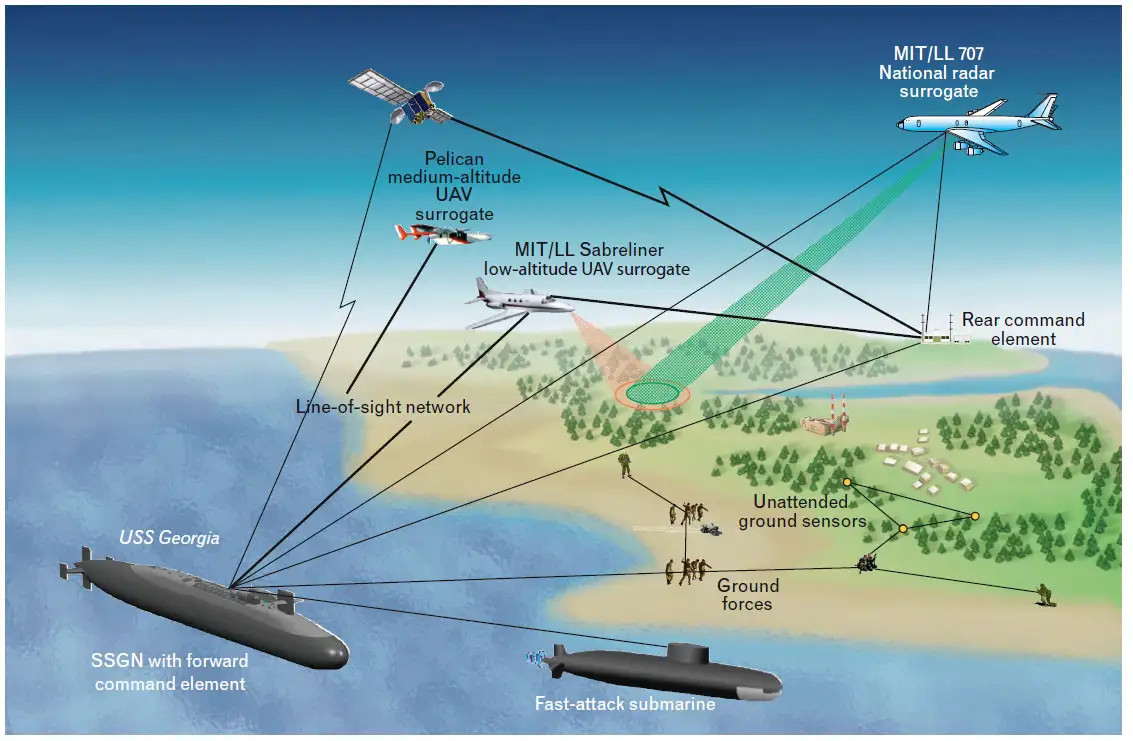

In 2004, in cooperation with the Air Force, the aircraft also demonstrated various communications and data-sharing capabilities during a Joint Forcible Entry Exercise (JFEX). A previous Air Force news item described the plane’s participation in that event as follows:

“Task Force Paul Revere, an airborne battle management command, control and communications application, helps makes testing machine-to-machine capabilities and global communication experiments possible by sending and receiving data between other airborne and space sensors and the Combined Air and Space Operations Center. This capability could allow United States and coalition warfighters from all services to simultaneously communicate from around the globe.”

“Currently, aircraft such as the Rivet Joint, Joint Surveillance Target Attack Radar System, U-2 or Airborne Warning and Control System take in information that is saved on disks, analyzed and manually sent to warfighters and planners. Today’s output bandwidth from these aircraft is limited. Task Force Paul Revere experiments with the capability of taking in information from ground, space and air assets and simultaneously and instantly sending the information back out on a global network that includes the CAOC.”

“During JEFX, Task Force Paul Revere is connecting information to Washington and routing it back through the base here.”

The aircraft also supported work on in similar veins in the mid-to-late 2000s, all of which notably took place around the time of the development of the Air Force’s Battlefield Airborne Communications Node (BACN) communications gateway. You can read more about BACN in this past War Zone feature.

In 2004, the modified 707 had played the role of an airborne radar with synthetic aperture and ground-moving-target indicator capabilities during a U.S. Navy exercise nicknamed Silent Hammer, which helped prove out various concepts of operation related to that service’s converted Ohio class guided missile submarines. You can read more about those specialized boats in detail, as well as that transformational exercise, in this past War Zone feature.

Starting in 2011, the modified 707 began supporting Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center projects, including the Family of Advanced Beyond-Line-of-Sight Terminals communications program, as well. The Lincoln Laboratory says that the jet has also been involved in the testing various radars, including phased arrays and a laser radar called Jigsaw, over the years.

“The teams who work through this test bed [sic] have truly put some of the best technology in the hands of the warfighter, and we really appreciate what you all have done,” Eric Evans, the Lincoln Laboratory’s Director, said at a retirement ceremony at Hanscom for N404PA in October.

“We achieved things with that aircraft that… definitely advanced both our understanding and our appreciation, and helped raise the spirit of why we do what we do each and every day,” Niles Cocanour, a retired Air Force Colonel who had worked with the Lincoln Laboratory team operating N404PA, also said at the event.

Despite Shashambre’s retirement, the Lincoln Laboratory will continue to provide flight test support for U.S. military programs with its other aircraft, a fleet that presently includes Dassault Falcon 20 and Gulfstream business jets, DHC-6 Twin Otter turboprops, and Cessna 206 single-engine plane. The MIT research center also works with other U.S. government agencies on flight test work, including experiments utilizing NASA’s unique WB-57F aircraft, which you can read about more here.

Of course, none of the Lincoln Laboratory’s remaining aircraft are nearly as eye-catching or uniquely capable as its now-retired heavily modified Boeing 707.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com