Under the darkly ironic codename Operation Vegetarian, the United Kingdom developed a scheme to respond in kind should Nazi Germany unleash a biological warfare attack on the British mainland during World War II. The fear of Hitler employing germ warfare was very real, intensifying after the fall of France in the summer of 1940, after which the United Kingdom was expected to be the next major target of the German military conquest of Western Europe.

Chair of the Bacteriological Committee in the United Kingdom, Lord Maurice Hankey urged Prime Minister Winston Churchill to look into the practicality of biological weapons “so as to put ourselves in a position to retaliate if such abominable weapons should be used against us.” Churchill agreed and set up a team of scientists at Porton Down, a top-secret laboratory in Wiltshire, southwest England, to embark on a project examining options for reprisal — should it ever be needed.

The choice of biological weapon fell on anthrax. Caused by the bacteria Bacillus anthracis, anthrax is a familiar agent of biological warfare. Anthrax spores occur in nature and can be produced in a lab. The spores can be delivered in the form of powders or sprays, or via contaminated food and water, and can persist in the environment for decades. Humans contract the disease when spores enter the body via a cut or scrape (cutaneous anthrax), via inhalation (pulmonary) or by consumption of infected meat (gastrointestinal). While pulmonary is the most lethal (around 80% mortality, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration), the gastrointestinal version used for Operation Vegetarian still results in death in between 25% and 75% of cases. These figures all depend on levels of exposure and availability of antibiotics, which can usually treat cutaneous anthrax.

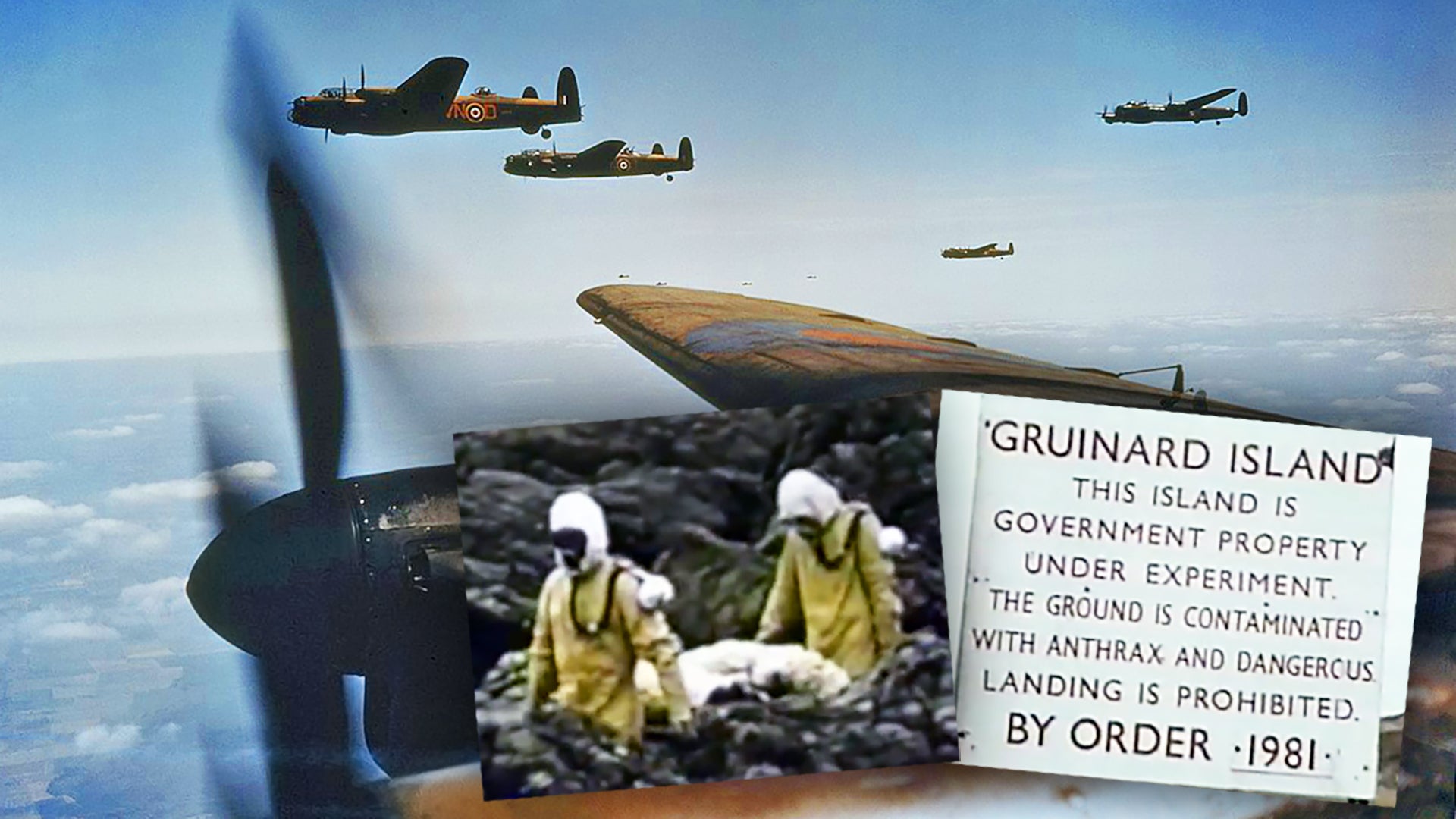

Tests were conducted on Gruinard Island on Scotland’s north coast and on Penclawdd off the Welsh coast. The former was bombarded with anthrax spores from the air by Vickers Wellington medium bombers, killing the island’s resident sheep within three days. Penclawdd, meanwhile, was attacked by a Bristol Blenheim in a follow-up test. The twin-engine bomber delivered a single device from around 5,000 feet. Its target was two lines of sheep — 60 in all — placed downwind of the impact point. The three pounds of liquid anthrax spores were found only to have killed two animals outright. Nevertheless, after these trials, anthrax was judged 100 times more effective than a chemical agent on a weight-for-weight basis.

January 1942 saw the go-ahead for Britain’s production of anthrax on a large scale with the War Cabinet simultaneously recommending that it be used against Germany as a reprisal weapon if Britain was attacked using germ warfare. Porton Down scientists by 1943 had produced an operational stockpile of five million cattle cakes infected with anthrax spores. Under Operation Vegetarian, these were to be delivered by Royal Air Force Avro Lancaster bombers — 12 in total — that would drop the deadly cargo over northern Germany. Aiming for farmland rather than population centers, the scheme was planned to wipe out the country’s beef and dairy cattle. As well as removing a vital food source, the bacterium would also work its way into the human food chain that was expected to lead to fatalities numbering tens or hundreds of thousands, if not millions.

The Lancaster was an obvious choice for the mission, had it ever been sanctioned. The four-engine type had entered service in December 1941 and would go on to excel both as a conventional heavy bomber and in a range of more unconventional missions, including dropping the 22,000-pound “Grand Slam” earthquake bomb and the “Upkeep” bouncing bombs that breached German dams in the raids of May 1943.

Of course, Hitler never sanctioned the use of biological warfare for reasons that have never been fully explained. It’s been speculated he may have had an aversion to germ warfare based on his experience of being gassed in World War I or his phobia of microbes. The Nazis nonetheless carried out research in this area including establishing an entomological institute to study the physiology and control of insects that inflict harm to humans.

British anthrax stockpiled under Operation Vegetarian was ultimately destroyed at the end of the war — all but two crates of infected cattle cakes were incinerated. It’s not clear what became of the remainder, but the spores they contained were still judged to be effective as of 1955.

The defeat of Nazi Germany was not the end of British interest in biological warfare. On the contrary, with the beginning of the Cold War, the focus now turned to the Soviet Union, which had begun its own experiments in the field before World War II and which had captured a Japanese biological weapons facility in Manchuria.

The effect of the anthrax tests on the British islands was dramatic and long-lasting, including reports of livestock deaths on the Scottish mainland after an infected sheep carcass from Gruinard was washed up on a beach. According to Porton Down’s official account, the mile-long island was not fully decontaminated until 1986 following a painstaking sterilization process amid mounting public pressure.

Today, Porton Down continues to play a role in biological and chemical weapons – rather than developing them for potential wartime use, it’s now tasked with developing countermeasures. It was also a focus of attention in the wake of the poisoning by nerve agent of former Russian military officer and double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter, Yulia Skripal, in nearby Salisbury in March 2018.

Operation Vegetarian — details of which for many years remained within classified the National Archives — is clearly one of the more extreme plans hatched by the Allies during World War II, but it’s a clear reminder of the kind of thinking at the highest military levels during one of the darkest periods in Europe’s history.

Contact the author: thomas@thedrive.com