While the news has been filled with claims that strange unidentified craft with unexplainable capabilities are appearing over highly sensitive U.S. installations and assets as of late, a much less glamorous, more numerous, and arguably far more pressing threat has continued to metastasize in alarming ways—that posed by lower-end and even off-the-shelf drones. Less than a year ago and just days after the stunning drone attacks on Saudi Arabia’s most critical energy production infrastructure deep in the heart of that highly defended country, a bizarre and largely undisclosed incident involving a swarm of drones occurred on successive September evenings in 2019. The location? America’s most powerful nuclear plant, the Palo Verde Nuclear Generation Station situated roughly two dozen miles west of Phoenix, near Tonopah, Arizona.

In a trove of documents and internal correspondences related to the event, officials from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) described the incident as a “drone-a-palooza” and said that it highlighted concerns about the potential for a future “adversarial attack” involving small unmanned aircraft and the need for defenses against them. Even so, the helplessness and even cavalier attitude toward the drone incident as it was unfolding by those that are tasked with securing one of America’s largest and most sensitive nuclear facilities serves as an alarming and glaring example of how neglected and misunderstood this issue is.

What you are about to read is an unprecedented look inside a type of event that is less isolated in nature than many would care to believe.

A Rapidly Accelerating Threat

Troubling incidents of protracted activity by swarms of drones, including a series of very strange incidents in Colorado and neighboring states last year that the mainstream media was quick to blow off without any real evidence to prompt such a dismissal, are occurring over and near some of America’s most critical infrastructure. These events are occurring as lower-end and lower-performance unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) have become weaponized to increasingly remarkable degree in recent years. Even those built-in sheds in the middle of warzones have been employed with not only deadly, but also a highly disruptive effects. As we mentioned a moment ago, drones have even inflicted major damage to one of the world’s richest and most heavily defended country’s cash cow—oil production. They have also been used in an attempt to assassinate a country’s ruler. And yes, the potential for them to be used for similar purposes exists right here in the United States, as well.

Even as lower-end drones that are armed with explosives and capable of precision attacks are being mass-produced overseas and America’s adversaries are openly perfecting far more complex swarm capabilities, the U.S. military and federal agencies are desperately trying to play catch-up to the threat even though they had years to proactively work to nullifying it before its inevitable manifestation. It wasn’t before weaponized drones were careening into and dropping bomblets on Iraq soldiers’ heads during the Battle of Mosul that the U.S. military had no choice but to begin to take the issue seriously. Today, American soldiers deal with the ominous presence of drones overhead and even dropping munitions daily in overseas hotspots. America’s top military commander in the Middle East is all too aware of this compounding threat and the lack of resources being placed on countering it:

“I argue all the time with my Air Force friends that the future of flight is vertical and it’s unmanned,” U.S. Marine General Kenneth McKenzie, head of U.S. Central Command, said at an event hosted by the Middle East Institute last week. “I’m not talking about large unmanned platforms, which are the size of a conventional fighter jet that we can see and deal with, as we would any other platform.”

“I’m talking about the one you can go out and buy at Costco right now in the United States for a thousand dollars, four quad, rotorcraft, or something like that that can be launched and flown,” he continued. “And with very simple modifications, it can make made into something that can drop a weapon like a hand grenade or something else.”

…

“Right now, the fact of the matter is we’re on the wrong side of that equation.”

With all this in mind, it isn’t a matter of if similar events will occur in the homeland, it’s a matter of when and of what scope. As it sits now, all the warning signs are there, especially in terms of where mysterious swarms of drones are popping up without explanation.

Two Nights In Late September

Douglas D. Johnson, a volunteer researcher affiliated with the Scientific Coalition for UAP Studies (SCU), was able to obtain a large number of internal documents regarding the September drone incidents at Palo Verde from the NRC via the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) and kindly shared them with The War Zone. It is important to note that these documents primarily reflect the NRC’s perspective rather than that of any other U.S. government agencies at the federal, state, or local levels. The Arizona Public Service Company, which operates the Palo Verde Generating Station, is also a private entity not directly subject to the FOIA.

Johnson did also submit a FOIA request for relevant documents to the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). DHS said it found 32 pages of documents related to the incident from CISA, but declined to release them, citing exemptions related to law enforcement activities. Another 17 pages of relevant records are still undergoing a review by the Transportation Security Administration (TSA).

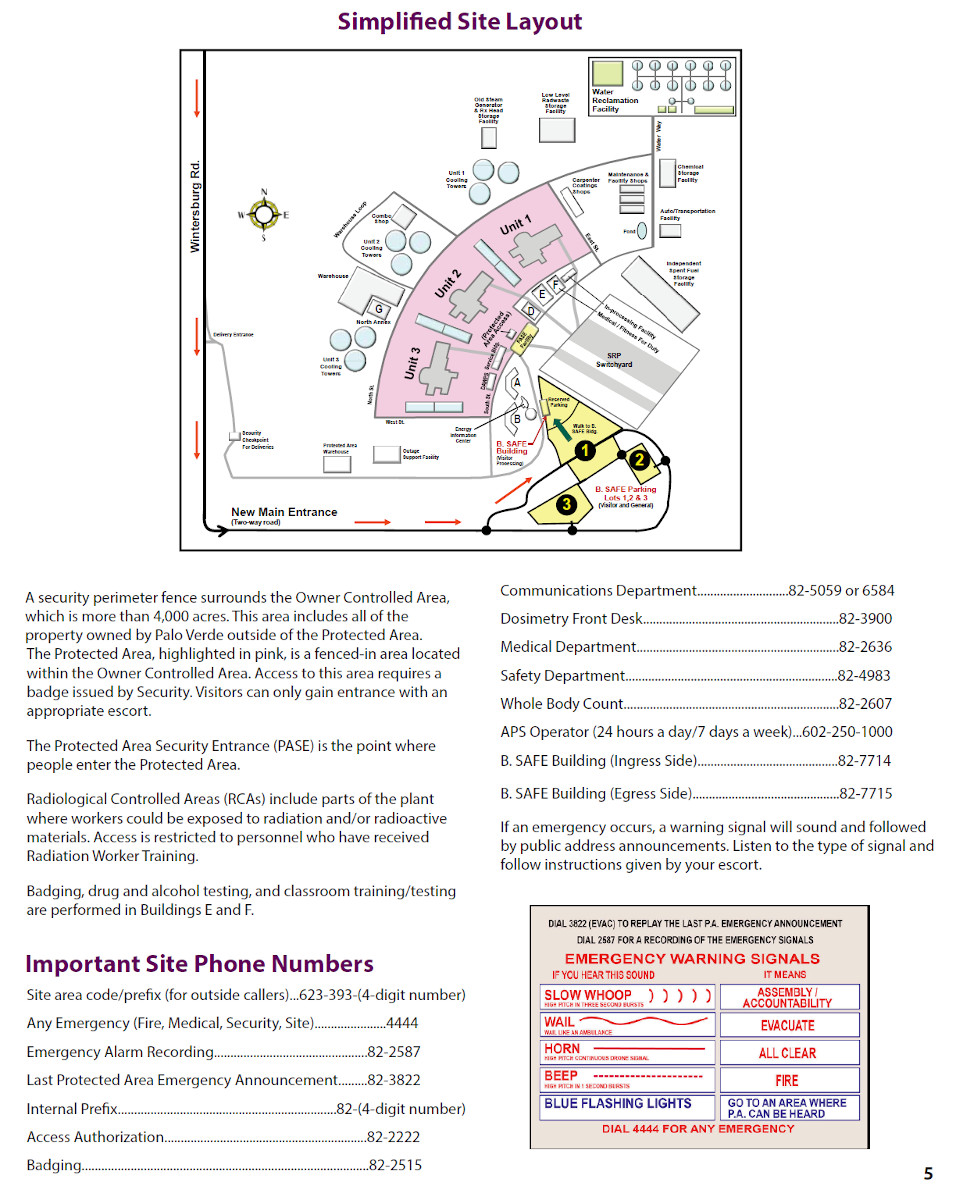

This particular story starts on Sept. 29, 2019. Shortly before 11:00 PM local time at the Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station, Daphne Rodriguez, an Acting Security Section Chief at the plant, called the duty officer at NRC’s Headquarters Operations Center (HOC). Rodriguez reported that a number of drones were flying over and around a restricted area near the nuclear power plant’s Unit 3, which houses one of its three pressurized water reactors.

Thomas Kendzia, a Headquarters Emergency Response Officer (HERO) at the HOC, subsequently created an incident report in the NRC’s Security Information Database (SID). The HOC’s policy is to have one Headquarters Operations Officer (HOO) and a Headquarters Emergency Response Officer (HERO) on duty, 24 hours a day, every day, with no exceptions. “The designated HOO for the shift has the primary responsibility for receiving reports and determining appropriate actions. The HERO counterpart role provides procedural, communications, and administrative support,” according to a 2018 NRC Office of the Inspector General’s report on headquarters staffing issues.

The key portions of the SID entry that Kendzia created, which was then updated as time went on, are as follows:

“Officer noticed several drones (5 or 6) flying over the site. The drones are circling the 3 unit site inside and outside the Protected Area. The drones have flashing red and white rights and are estimated to be 200 to 300 hundred feet above the site. It was reported the drones had spotlights on while approaching the site that they turned off when they entered the Security Owner Controlled Area. Drones were first noticed at 2050 MST and are still over the site as of 2147 MST. Security Posture was normal, which was changed to elevated when the drones were noticed. The Licensee notified one of the NRC resident inspectors.

As of 0237 EST, no drones have been observed at the site since 2230 MST. Officers believe drones were over 2 feet in diameter.

Personnel at the HOC also then called the duty officer at the NRC’s Intelligence Liaison and Threat Assessment Branch (ILTAB), a division of the Office of Nuclear Security and Incident Response. ILTAB’s mission is to “provide strategic and tactical intelligence warning and analysis of all threats to the US commercial nuclear sector, and serve as NRC’s liaison and coordination staff to the US intelligence and law enforcement communities,” according to a 2010 briefing.

That wasn’t the end of it, though, for Palo Verde. The very next night, Ismael Garcia, a Security Supervisor at the plant called ILTAB to report another drone incursion over sensitive areas.

This new information was originally added as an update to the previous incident, but the HERO on duty, Donald Norwood, eventually set up a new, separate SID entry, which again received additional updates as the situation progressed, with the key details being as follows:

Four (4) drones were observed flying beginning at 2051 MST [on Sept. 30, 2019] and continuing through the time of this report (2113 MST). As occurred last night, the drones are flying in, through, and around the owner controlled area, the security owner controlled area, and the protected area. Also, as last night, the drones are described as large with red and white flashing lights. Spotlights have not been noted tonight.

The licensee has not changed their security posture. The licensee continues to monitor the drones.

As of 0355 EDT, no drones have been observed at the site since before 0020 MST. LLEA [local law enforcement agency] surveyed the area and were unable to locate drones on the ground or anyone controlling the drones.

The licensee notified FAA (both Phoenix and Albuquerque), FBI, DHS, and the Maricopa [County, Arizona] Sheriff’s Office. The licensee notified the NRC Resident lnspector.

Palo Verde security officials had filed their own report on this second incident, which eventually made its way to NRC. It included the following narrative:

“On 9/30/19 at approximately 2051 hours, it was reported by a Security Team Leader that Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) were approaching the plant from the east (true east). The hours of darkness made it difficult to estimate the altitude at which the UAVs were flying. Two Security Team Leaders [redacted]. The UAVs appeared to have been launching from behind the mountain range at the intersection of Southern Ave and 361 Ave just east of the plant. Four UAVs were confirmed to have been spotted at one time flying northwest over Unit 1 and returning northeast over Unit 3. LLEA (MCSO) [Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office] deputies were dispatched to the area of the mountain range with a Security Unit Team Leader in an attempt to determine the location of the UAV operators, but were unsuccessful. No other UAVs were observed after approximately 2300 hours.”

“These UAVs are believed to have been the same UAVs that flew over the plant the night before on 9/29/19 at approximately 2020 hours (refer to CR# 14095 for details).”

“All required notifications were made IAW [in accordance with] 20DP-0SK49 Security Integrated Response Plan and additional Security contingency measure [sic] were implemented IAW 21SP-0SK11 Security Contingencies. No additional compensatory measures are required IAW 20SP-0SK08 Compensatory Measures for Loss of Security Equipment/Effectiveness.”

A Futile Distraction?

Curiously, one of ILTAB’s top priorities seemed to be getting the staff at Palo Verde, or anyone from any other NRC-licensed facility, to stop calling them in the middle of the night about reported drones. “Our folks got calls last night at 2am, which is correct per the procedure,” Laura Pearson, ILTAB’s chief, wrote an Email on Sept. 30 to Silas Kennedy, the Chief of the Operations Branch within the Division of Preparedness and Response of NRC’s Office of Nuclear Security. “However, I am wondering if there is a way to cut down on calls in the middle of the night for issues that ILTAB can’t add value to,” Pearson continued. “The call last night about drones is a good example-in the middle of the night, ILTAB can’t really do anything about it anyway apart from say ‘ok thanks’ and handle it in the morning.”

Pearson raised concerns that the late-night calls “interrupts sleep” and that her staff would then arrive at work “either groggy or come in late, so there’s negative returns on it from an, organizational perspective.” Kennedy told her that ILTAB could, on its own accord, change its requirements for when personnel at nuclear sites would need to immediately contact the duty officer to report an incident.

Before the second drone incursion had even occurred on Sept. 30, ILTAB was already working on revising its instructions from when the HOC staff should contact them. Pearson also asked Kennedy if there was a way to halt all calls about drones in and around Palo Verde, specifically. “There is nothing ILTAB can do about it at night, and if my staff has to be woken up about it each night, it will start to cause other problems for us. We have a small staff and having people out or late because they are not getting adequate sleep will impact our ability to get work done,” she wrote in another Email on Oct. 1.

“Please place a note in the turnover log stating ‘Until further notice, do not call the ILTAB duty officer from 10 pm until 6 am for drone flyovers of Palo Verde. Send an email to ILTAB in the morning. This is specific to Palo Verde only. For all other licensed facilities, continue to follow HOO procedures until changes are made,’” Kennedy subsequently instructed other staff at the HOC.

At that time, per a subsequent Email, the list of instances in where HOOs or HEROs were supposed to immediately notify ILTAB included, but were not necessarily limited to the following:

- Ongoing security events. (basis for the drone calls since they were loitering in the OCA [owner controlled area])

- Verbal/telephone/e-mail threats.

- Bomb threats.

- Threats to site employees.

- Fence jumpers/intrusions.

- Security barrier penetrations.

- Discovery of weapons or explosives.

- Event involving law enforcement response/investigation on the owner-controlled area (OCA) or watercraft exclusion areas.

- Event involving FBI investigation.

- Security-related media attention at any level.

- Sabotage/Tampering.

Other NRC officials appear to have been unsure as to how they could necessarily help in responding to the incidents, in general. “[Palo Verde] Site security was unable to observe any identifying markings on the UAVs themselves or locate the operator(s), so I do not know how much additional investigation can be undertaken,” an Intelligence Specialist at the Response Coordination Branch for NRC’s Region IV, whose name is redacted, wrote in a separate Email.

Inconclusive Investigation

The situation on the ground at Palo Verde was completely different. By Oct. 2, officials at the plant were working together resident NRC personnel, as well as local law enforcement, the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). A subsequent Email shows that the FBI’s Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) Coordinator was specifically contacted in relation to the drones.

They were also in the process of deploying unspecified drone detection systems acquired from a company identified in one Email as “Area Armor.” This is very likely an error in referring to Aerial Armor, which describes itself as having “been at the forefront of the drone defense industry since 2015 as a service provider and systems integrator for C-UAS solutions.” The company’s website also says “On countless deployments, we’ve worked hand in hand with local law enforcement, FAA, FBI, DHS and private security professionals throughout the US.”

“This technology apparently has a 13-mile radius and can determine the specific point from which the UAVs were launched so that LLEA / site security can locate the operator(s),” a Region IV Response Coordination Branch Intelligence Specialist, with their name redacted, possibly the same individual referenced earlier, wrote in an Email. “I confirmed with the licensee that they have coordinated the use of this counter drone technology with FAA, and they informed me that this technology only locates the UAVs; it does not interfere with the flight pattern of those UAVs in any way.”

Aerial Armor supplies drone detection systems from various manufacturers, including small radars and ones that work by spotting and tracking the unmanned aircraft’s signal emissions. Some of them also include full-motion electro-optical and infrared video cameras that can be slewed to visually monitor targets of interest after the other sensors spot them.

It’s not entirely clear what drove the decision at the time by the Palo Verde staff to set up systems to detect rather than knock down the drones. It’s possible that the detections systems were the only ones readily available or that this was the established protocol for security at the plant at the time.

Regardless, it underscored serious questions about what the plant operators could actually do, legally, in response to the intrusions. “At this time, the pilots are not violating any laws or regulations by flying over the plant,” Joseph Rivers, a now-retired Senior Level Advisor on Security for NRC, wrote in an Email on Oct 2.

“Since drones are aircraft and they are not violating a law, what is the action that can be taken legally if they locate the operator?” Mark Lombard, the Deputy Director of NRC’s Office of Nuclear Security and Incident Response, asked in response. The next Email in the chain is unrelated to that question and the one after that is redacted entirely. The last message in this particular string is also heavily censored, though it does say that “NEI has a drone working group and we will bring these examples to them.” NEI very likely refers to the Nuclear Energy Institute, a nuclear energy trade association and lobby group in the United States.

It’s unclear if whoever was flying the drones was still violating FAA regulations, which ban unmanned aircraft from flying lower than 400 feet over “designated national security sensitive facilities,” which includes nuclear power plants, even if they weren’t technically breaking any laws. Arizona also has its own state law prohibiting drones from flying under 500 feet over any critical infrastructure, including power plants.

Without knowing the exact altitude the drones were flying at during the incursions, it’s difficult to say what the exact legalities of the situation were. We also don’t know for sure if authorities at Palo Verde didn’t deploy counter-drone systems capable of actually knocking down unmanned aircraft later, though NRC’s officials never mention any such development in the documents The War Zone reviewed.

What we do know is that by Oct. 3, with assistance from the FBI and the Department of Energy, officials at Palo Verde had begun the process of rectifying that situation and getting the airspace over the plant designated as restricted through the FAA.

“DOE is working closely with FAA to designate areas over NPPs [nuclear power plants] are no-fly zones and we are working to communicate to licensees what that means,” Deputy Director Lombard wrote in an Email the following day. “At this time, we are not planning to impose new requierments [sic] on licensees, but the landscape is dynamic and changing.”

None of the authorities involved in subsequent investigations into the two drone incursions over Palo Verde were able to determine the operators of the drones or their intent. ILTAB followed up with other officials within NRC on Oct. 28 to see if there had been any new developments and had marked the two SID entries “closed unresolved” by Nov. 25.

Not An Isolated Incident

Whatever the exact story of what happened at Palo Verde might be, the internal Emails from NRC make clear that this was not an isolated incident. “We also had several high speed drones over Limerick [Generating Station in Pennsylvania] that caused a VP to call about 8 months ago,” Brian Holian, Director of NRC’s Office of Nuclear Security and Incident Response, wrote at one point.

“Yes, I agree that both of these overflight incidents at Palo Verde meet several criteria that we have historically used in triaging UAV overflights as particularly worthy of follow-up (# of UAVs involved, time of day, length of overflight, maneuvers, etc.),” another individual whose name is redacted added in the same Email chain.

Another response, from another redacted individual, is censored almost entirely. “Just my two cents worth of an observation. I’m off to a tabletop exercise,” the Email concludes with.

After the Palo Verde incidents, officials at ILTAB went back and checked and found 42 drone-related incident reports entered into the Security Information Database since 2016, including the two at the Arizona plant. There were another 15 in the system when they searched all the way back to Dec. 27, 2014. This includes another one involving a drone at Palo Verde, also “closed unresolved,” on Dec. 21, 2017. NRC redacted information about all of these remaining cases as “non-responsive” to Douglas Johnson’s FOIA request.

It’s also clear that NRC hasn’t been the only U.S. government entity grappling with this issue. Another Email notes that the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), part of the Department of Energy, had recently added a “suspicious activity reporting requirement” with regards to incidents at sites under its jurisdiction, but that it was also unclear as to how to approach drone incursions, necessarily.

“I just met with Shana Helton [Director of the Physical & Cyber Security Policy Division of the Office of Nuclear Security and Incident Response] and Jeremy Bowen [Deputy Director of the Office of Nuclear Regulatory Research] for a detailed discussion about drones, FERC, and where we are with reporting requirements,” Geoffrey Miller, Deputy Director of the Reactor Safety Division at the NRC’s Region IV office, wrote.

“I look forward to that discussion,” an individual, whose name is redacted, responded. “I would love to have a better understanding of where we

are going as an Agency on the topic of drones.”

“This week has been Drone-a-palooza for ssure [sic],” the Office of Nuclear Security and Incident Response’s Deputy Director Lombard had written in an Email on Oct. 4. “With the two drone swarm flyovers at PVNGS [Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station] early in the week getting a lot of attention in the agency and outside (e.g., folks who work in the EEOB [Electrical Engineering Operating Reactors Division of the Office of Nuclear Reactor Regulation]), we learned a lot and briefed a lot. And our UAV/drone Commission paper should go up to them next week.”

Rules, regulations, and reporting requirements are, of course, just one part of the picture. Joseph Rivers, the NRC Senior Level Advisor on Security who was coordinating with various other individuals around the Palo Verde incidents, highlighted in one Email that none of this would do anything to directly prevent a hostile actor from using drones in a more nefarious way.

“I would point out that restricted airspace will do nothing to stop an adversarial attack and even the detection systems identified earlier in this email chain have limited success rates, and there is even lower likelihood that law enforcement will arrive quickly enough to actually engage with the pilots,” he wrote.

“We should be focusing our attention on getting Federal regulations and laws changed to allow sites to be defended and to identify engineering fixes that would mitigate an adversarial attack before there our licensed facilities become vulnerable.”

You can find the full copies of the NRC documents as they were released to us, broken into four parts here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4.

The Changes That Never Came

The “drone-a-palooza” over America’s most powerful nuclear powerplant represents an intriguing and puzzling mystery. Who had the capability to put at least around a half a dozen drones up over the plant for hours on two consecutive nights and why? The fact that drone incursions aren’t totally new there, or at other major nuclear facilities, is equally concerning. But above all else, these internal documents show just how naive those tasked with dealing with such threats are to the potential nefarious capabilities of readily available unmanned aircraft.

Could smaller weaponized drones have the capability to trigger a catastrophic radiological event at a powerplant like Palo Verde? These facilities and the nuclear waste stored on their grounds are hardened to some degree, but that’s not really the point. Even throwing the plant into disarray and disabling it for a protracted period of time could have substantial impacts on the region as millions depend on the plant for power. Coordinated attacks on other plants across a region could have even more damning, if not somewhat unthinkable impacts.

Strategically speaking, a standoff capability with such a low barrier of acquisition, ease of use, and with such a high-chance of evasion for its perpetrators, is highly troubling. We will talk about these elements and tie together many other threads we have been weaving over the past year in an upcoming post, but for now, the Palo Verde drone scare of 2019 should be yet another reminder of how far we are behind dealing with this threat on a legislative, informational, and defensive level.

Oh, and if you think this event may have served as something of a wakeup call for the powers that be, you are mistaken. Just a month after it occurred, the NRC made the highly controversial, if not outright dubious decision to formally decline to require owners of U.S. nuclear power and waste storage facilities to be able to defend against drones.

“Staff has determined that nuclear power plants and Category I fuel cycle facilities do not have any risk-significant vulnerabilities that could be exploited using UAVs and result in radiological sabotage, theft of special nuclear material (SNM), or substantial diversion of SNM,” according to NRC’s review. “Similarly, the staff has determined that information gained from UAV video surveillance of an NRC-licensed facility is bounded by the type of information that could be provided by the knowledgeable insider currently permitted in the DBTs [Design-Basis Threats].”

Physicist Edwin Lyman, acting director of the Nuclear Safety Project at the Union of Concerned Scientists, a nonprofit organization, stated the following about the decision:

“The NRC’s irresponsible decision ignores the wide spectrum of threats that drones pose to nuclear facilities and is out of step with policies adopted by the Department of Energy and other government agencies… Congress should demand that the NRC require nuclear facility owners to update their security plans to protect against these emerging threats.

Many companies are developing technologies to protect critical infrastructure from drone attacks through early detection, tracking, and jamming… If the NRC were to add drones to the design basis threat, nuclear plant owners would likely to have to purchase such systems. Laws would also have to be changed to allow private facilities to disrupt hostile drone flights. But plant owners are loath to spend more on safety and security at a time when many of their facilities are struggling to compete with cheap natural gas, wind and solar.

The NRC seems more interested in keeping the cost of nuclear plant security low than protecting Americans from terrorist sabotage that could cause a reactor meltdown… The agency needs to remember that it works for the public, not the industry it regulates.”

Sadly, it’s unlikely that any action will be taken when it comes to the threat posed by lower-end drones until a catastrophe occurs. We will discuss just how much is at risk and highlight other even more concerning incidents that have all but proven how capable such an asymmetric and inconvenient threat can be in the very near future.

Regardless, the Palo Verde incidents serve as yet another warning of the potential dark side of the drones that fly among us daily.

Contact the authors: Tyler@thedrive.com and Joe@thedrive.com

You can reach Douglas D. Johnson via @ddeanjohnson on Twitter.