Even though AeroVironment’s products, or at least emulations of them, have starred in a number of Hollywood Blockbusters and extremely high-profile video games, few outside the defense community have ever really heard of the company. The reality is that AeroVironment is among the most fascinating and visionary aerospace companies on the planet. They saw the potential in lower-end drones that could be deployed by those on the front lines before pretty much anyone else did, and changed warfare as we know it as a result.

Though its hand-launched Raven reconnaissance drone is its most widely distributed product, AeroVironment’s Switchblade, which is launched like a mortar and works as both a reconnaissance drone and a deadly missile, is probably its most intriguing. Often referred to as a ‘suicide drone’ in informal parlance, in so many ways Switchblade was a harbinger of what was to come.

Now, with lower-end drones becoming consumer goods and new innovative concepts, like swarming, distributed reconnaissance, and other advanced networking architectures having begun to take center stage, AeroVironment sits with a pedigree like few if any other aerospace firms have to take full advantage of the drone revolution. This means migrating existing products to different launch platforms—like submarines, armored vehicles, and unmanned combat air vehicles—and the invention of totally new products that further break down the cost and temporal barriers of close air support, airborne reconnaissance, and even telecommunications.

With all this in mind, The War Zone talked in-depth with AeroVironment’s Chief Marketing Officer, Steve Gitlin, about the company’s storied lineage, its established game-changing product lines, and what is coming on the horizon not just for them, but for the brave new world unmanned warfare in general.

Tyler: Steve, can you just give us an idea of what your position is in the company and how you ended up with the AeroVironment?

Steve: So, I’m Chief Marketing Officer and I’m also in charge of our strategic planning at the company and I joined the company actually in 2002… I’ve kind of grown as the company has grown. When I came to the company, we were probably 200 and change people, $25 to $30 million in revenue. Last fiscal year, we were knocking on 800 people and $214 million in revenue…

The company was founded, as you probably know, by Dr. Paul MacCready, who was, among other things, known as the father of controlled human-powered flight. He designed the Gossamer Condor, the first human-controlled, human-powered airplane, that’s now in the Smithsonian collection… That led to a DNA of problem solving and innovation that has fortunately stayed in the bloodstream of the company and has powered the innovation that’s driven us to where we are today.

We really compete in three main areas, tactical unmanned aircraft systems primarily for reconnaissance and information collection, tactical missile systems for precision surgical strike, and high-altitude pseudo-satellites or high-altitude long-endurance [HALE] systems… We’re active in each one of those areas. We’ve been active really since—well, we’ve been active in tactical missile systems since the early 2000s and in tactical unmanned aircraft systems and high-altitude pseudo-satellites since the 1980s.

We believe in each of those spaces and support early adopters ensuring they are successful and then growing as the demand for solutions has grown. We’ve got a group called MacCready Works that’s working on far-reaching stuff that we believe has an opportunity to turn into meaningful new products and markets and capabilities in the future.

Tyler: Switchblade is probably your most known of your products, at least in the media, because it’s whatever you wanna call it, a missile system, or suicide drone. Can you describe the system as it exists today? What control concepts does it use? Is it all man-in-the-loop or is there any sort of movement to give it some sort of autonomy, both in terms of flying the aircraft and in the targeting and execution of those targets?

Steve: Great question. Let me begin by giving you a little bit of background of how Switchblade evolved. So, when we equipped soldiers and Marines and special forces with our tactical unmanned aircraft systems like Raven, Puma, and Wasp, Raven being the most prolific military drone in the world, they began recognizing the benefits of that on the frontline. Now, for the first time, frontline warfighters had the ability to gain situational awareness and actionable intelligence wherever they were, wherever they were, whatever the conditions at the time, and they didn’t have to depend on some other unit or some other asset to be made available to do that for them or have to send people into harm’s way to find out what’s over the next ridgeline or what’s on the other side of that wall.

So, having these portable tools, hand-launchable tools, organic assets, gave them incredible capabilities… But then, as they gained experience with them, they came back to us and said, “Wow, we love this, this is really… It helps us succeed, but what we would really like to do is that now that we can find the threat, we’d like to be able to address that threat, equally, rapidly, accurately.” So, that really led the development of Switchblade, which is the integration of many of the technologies underlying our tactical unmanned aircraft systems, but integrating them into a different architecture that you’ve launched, wing spring open type of an architecture and with a high explosive warhead.

As we began showing that to customers, they got really interested in it to the point where they began co-funding our development. Then the Army’s first public announcement that they were being used by the Army was in, I believe, December 2012, when they had been deployed to Afghanistan. Since that time, that’s grown to become a very important part of our business.

So, back to your question, what’s the concept of deployment? These are portable assets. They’re transported in the tube that they fire from. The tube is set up like a little mortar on the ground. And using the ground control system, the operator launches it. It exits the tube. Its wings spring open. Its propeller spins up, and it starts flying in the direction the operator wants it to and streaming live video back to that operator, viewable on the screen in the middle of that hand-control unit.

Once the operator identifies the threat, be it a sniper or somebody laying wait in ambush, they then designate that target on the control station screen, and the Switchblade then navigates itself in the terminal guidance mode and detonates on to that target. It does so in such a way that if there are non-combatants nearby, they won’t be harmed but the target will obviously be neutralized. So, that concept of operation involves a man-in-the-loop and it could also be GPS designated, for example, if something’s not moving. Because of the way we designed the system, because of the algorithms we developed, if the target moves or starts heading in a different direction, the Switchblade will actually follow that target, which is a very helpful capability.

Tyler: It’s a hybrid system with man-in-the-loop and some autonomy at the end there? It does its own end-game solution to kill that target basically?

Steve: Yeah, the designation of the target, the operator has to actually arm it. So, there’s a man-in-the-loop in the arming sequence.

Tyler: Right, but for it to actually find its way to hit the target really accurately, it’s not relying on a guy to basically fly the thing into the target itself. It does this in an automatic mode, once it’s been cleared to do so?

Steve: Similar to the way our tactical unmanned aircraft systems operate, unlike radio-controlled devices, the operator is not flying the aircraft, the operator’s simply indicating what he wants to look at, what he wants the camera to be pointing at, and the onboard computer flies the aircraft to that point and maintains on target. We have a similar capability in our tactical unmanned aircraft systems. You could lock in on a target and the aircraft will basically maintain position on that target, autonomous.

Tyler: Is your team working on any ideas to make it where it’s more autonomous as far as autonomous target recognition? Any of those sorts of ideas moving forward?

Steve: We’re working on a number of enabling capabilities that will benefit our entire product line and make them more capable, reduce the cognitive load on the operator, and ultimately result in greater accuracy and operations in denied environments. So, there are a number of capabilities. I can’t really get into details of them, but they’re very much on our roadmap and we look forward to being able to introduce those to customers.

One other interesting capability I should mention is the Switchblade could actually be used in tandem with one of our tactical unmanned aircraft systems. For example, if a unit is operating a Puma overhead, circling up a few thousand feet away, zooming in using the incredible i45 sensor that we developed for the Puma system, if the operators at Puma then identify a threat, the information and the geolocation information can be passed digitally directly to the Switchblade, which we then task to that target.

Tyler: Is Switchblade reusable at all or is it that once it’s launched, it’s gone?

Steve: It’s a single-use.

Tyler: Who are the customers today? Can you disclose anybody outside like the U.S. Army that’s using it?

Steve: So the Army, and more recently, the Marine Corps in the government fiscal year ’20 budget appropriations, the Marine Corps were in there for a procurement of Switchblade. So, Army and Marine Corps are public.

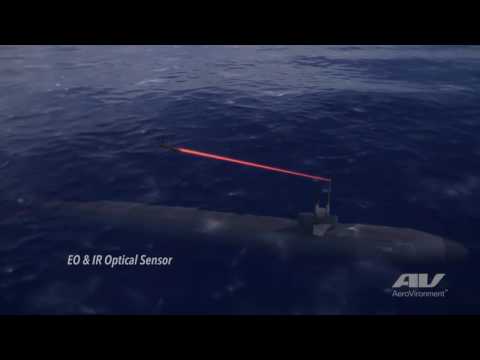

Tyler: I want to move on to Blackwing because it’s something that I think people just have a hard time understanding how big of a deal this is… So, just to start, can you talk a little about it and its development status or deployment status?

Steve: We developed Blackwing as one of the variants of Switchblade. As we were demonstrating Switchblade to early customers, some of them would bring other potential customers who got very interested in the capability and said, “We really like this, but we need it to be operated in this slightly different way,” and we began working on some of the variations of Switchblade. One of those variants, the first one we disclosed is Blackwing, which is a Switchblade type of a solution, but instead of a warhead, it carries extra batteries for longer flight endurance. And then, instead of being carried in a rucksack and set up on the ground, it’s actually launched out of existing tubes in submerged submarines, which is then launched in another sort of a device that takes it to the surface, and from the surface, it launches like the regular Switchblade.

The way I describe it is a remote-controlled periscope, sort of a remote-controlled periscope that extends the range dramatically for any kind of a submarine operation… And it doesn’t have to launch right away. It could be sent to the surface and set to launch at some later time when no submarine’s in the area.

It can be programmed to conduct a mission and because it incorporates the digital data link that AeroVironment developed for all of our tactical unmanned aircraft systems and Switchblade, not only can it collect information and generate situational awareness, but it can also act as a pop-up mesh network in the middle of the ocean to connect surface vessels to undersea vessels to manned vessels to unmanned vessels, and create basically a pop-up mesh network in the ocean.

Tyler: So it can act as a connectivity gateway, through via data link once it’s up there?

Steve: Yep, exactly.

Tyler: How does the submarine stay connected to it?

Steve: I would leave that to our customers to answer.

Tyler: It has a beyond line of sight capability, generally speaking?

Steve: So, it can be programmed to go to wherever you want it to go.

Tyler: Right. On autopilot, right? On a pre-disposed, pre-planned course, but they can fly it man-in-the-the loop if they’re within line of sight, correct?

Steve: If they maintain line of sight, yes.

Tyler: Has it been looked at to carry electronic warfare or decoys payloads, or any other sort of secondary uses? I’m sure you can put different payloads on it, right?

Steve: It, like other members of the tactical missile systems family and our small UAS, it really does offer lots of possibilities with the modularity of payloads and interchangeability of payloads and the batteries, for example, but our customers haven’t really gone into that level of detail and we won’t either at this point.

Tyler: With Switchblade and Blackwing, because they’re so related, have you looked at using the airframes to create swarms… Disposable swarms of drones that are networked together and work cooperatively?

Steve: We actually also developed a multi-pack launcher for Switchblade, which can house up to nine or 12 different Switchblades. Imagine a large box. And that’s really useful, for example, in a forward operating base, where the military forces that are occupying that FOB may not want to expose themselves to enemy fire, but they may be taking fire. So, rather than they all get up and put their selves at risk to try to find, fix, and defeat the enemy, with a multi-pack launcher, they could actually stay in a secure area, launch one or more Switchblades and target them to the threat that they’re facing. So in a way, that’s a kind of an answer to the question you’re providing or you’re asking. It enhances the capability of the warfighter and takes advantage of the capabilities of a Switchblade system.

You can watch a short video from Aeroviromant about the multi-pack launcher and how the company’s reconnaissance drones like Puma can work with Switchblade to prosecute targets in the maritime environment here.

Tyler: Any way of looking at infusing autonomy into that swarming concept where they can work cooperatively together? That might not be for attacking targets on the ground, but for surveillance of different types, or anything of that nature?

Steve: Well, as I mentioned before, we’ve got a good number of people focused almost entirely on underlying technologies that will enable different levels of autonomy. Our systems already have levels of autonomy, basic levels as some would describe. But our road map calls for much higher levels of autonomy that are going to enable multi-domain operations across dynamic battlefields, and some very interesting capabilities that we think our customers are gonna find quite valuable.

Tyler: What does the Switchblade cost?

Steve: We’ve not disclosed that… It’s a very competitive space.

Tyler: So you’re talking about sea launch, like a submarine launch, which is a very challenging environment… Are you looking into an air-launch variant of any of these or other systems?

Steve: One of the big differences between our tactical missile systems, Switchblade and Blackwing, for example, and our tactical unmanned aircraft systems is, in the TUAS part of our business, all of our fixed-wing assets are portable and rely upon an individual tossing them in the air to get them into flight. They can land. They do a deep stall landing and they just almost vertically land in a very confined area, so getting them down is not an issue. But once you automate the launch process, the launch sequence, by putting it into a tube and making it a push-button launch mechanism, that launch tube can be installed in a wide variety of platforms.

Submarine is one example, a multi-pack launcher is another. We have a TMA agreement with General Dynamics Land Systems, where we’re working with them to integrate Switchblade into a next-generation armored vehicle system for a new Army program. So in that concept, think of it as… where a convoy of armored vehicles are heading into a town. Before they even get there, the commander can actually launch a small UAS to scout the road ahead and see if there are any threats, and if they find a threat, they can then launch a couple of Switchblades to neutralize those threats before the convoy gets in harm’s way. And be able to follow up on it…

Tyler: And being able to also ‘look over a wall,’ right? That’s kind of the biggest thing, right? To be able to just look behind things?

Steve: Look over a wall, on top of a building, behind obstacles, behind a corner. Well, you name it. The other relationship we’ve developed is with Kratos, whom I suspect you’re familiar with… We’re working with Kratos to equip their unmanned fighter jets with Switchblade systems, so that those Switchblades would effectively be air-launched from that system… Using a flyer, they could be transported a great distance in a short amount of time, and then be deployed to neutralize any number of targets, whether they be human threats or infrastructure, or whatever. Whatever the need is.

Tyler: You could just think of the disruption of enemy air defenses. I’m sure you could put an RF Seeker on it… Are you talking about XQ-58? Are you talking about the Valkyrie drone?

Steve: It’s that program, yeah.

Tyler: We’ve seen sort of the democratization, I don’t know what to call it exactly, of drone technology via it moving to the commercial space. Where you guys were innovative with Switchblade years ago, and now the enemy has figured out, “Well, we can take a commercial drone that we can buy for 1,500 bucks and make it a weapon.” Where do you see that going in the future? Obviously, I’m sure you guys have an eye on it with the Iranian attacks and everything else. Can you comment a bit about that, and where the company sees that space heading in the future, and how is the best way we can defend against such threats?

Steve: Let me begin by taking a giant step backwards. If we look ahead five, 10, 15 years in the future, it’s hard to imagine a future where drone technology does not become pervasive in society. And that means delivering goods, delivering people, surveilling borders, scanning pipelines and power lines in remote areas that are difficult to get to, and monitoring traffic, you name it. There are so many applications where drone technology that’s obviously proven to be safe and reliable, combined with regulations in unmanned traffic management schemes, can enable all kinds of benefits for society.

Similarly in the military domain, we’ve talked about a number of ways, what we’re working on, that have the potential to dramatically help our warfighters and those of our allies operate more safely, more effectively, and also much more accurately. Because we, our country, cares a lot about the people who are not in the fight, making sure that if possible, we can avoid the collateral damage that is often an unfortunate byproduct of warfare.

So, these technologies can find their way into lots of different places. But to your point, that means that Pandora’s Box is open. That means all kinds of people can use drone technology for all kinds of things. And in addition to making sure that what our forces use and what we deploy in the national airspace for commercial operations or war operations are safe and reliable and effective, we have to be very cognizant of how the technology can be used against us.

As you know, there’s a lot of investment going into counter-drone technologies and ideas, and we’re tracking mostly with that, we understand that space very well. We haven’t really talked about anything we’re doing there, but let’s just say we understand it well. We believe that that’s going to be an important part of the mix. Being able to defend against adversaries using that against us is important.

Tyler: On drones, just the design of them, you look at your team’s products and they’re really different-looking. They have a unique look to them visually. There have been some moves to be able to better mask drones from the enemy and one of them is to make drones look a little bit more like biological lifeforms, birds mainly. Have Aerovironment played around with that, trying to take a Switchblade type of concept and making it look more like something that would just be in an environment that wouldn’t draw so many eyeballs?

Steve: Have you ever seen the Nano Hummingbird, robotic hummingbird drone?

Tyler: Yeah.

Steve: So we invented that. That was a DARPA project, but DARPA came to us with that same question, “We want you to develop a drone that looks and operates like a hummingbird,” and we created that demonstrator in about 2011, we showed it and it generated all kinds of interest. Now, that’s not a product, but it gives a sense for nanoscale, what you could possibly do to develop sort of a drone employing biological mimicry.

In terms of disguising any of our existing products to look like any other thing, we’re pretty focused on doing the things you see in front of you, the products you see on our website. There are certainly a number of other things that we do that we can’t talk about. But by and large… I’m not aware of any concerted effort to disguise any of our products to make it look like something they’re not.

Tyler: Let’s talk about High-Altitude Pseudo-Satellites… Obviously, there’s a huge commercial side of this, massive potential. But when we look at it from a defense side, is this something that could be used, say, with space being so contested… Could these systems be used to potentially replace certain communication capabilities or other satellite capabilities, like during a time of conflict?

Steve: We believe there are a number of potential applications for the technology. We think of it as a near-space asset above the clouds, above most air traffic that basically provides a platform. And on that platform, this platform is capable of carrying a certain amount of weight, size and provide a certain amount of power. So the commercial example is the Hawk30 that we’re developing for our joint venture with SoftBank that’s called HAPS Mobile, Inc that will carry a telecom payload into the stratosphere at about 65,000 feet and dwell there for months, acting as a stratosphere cell phone tower.

But you can imagine other kinds of payloads, whether they’d be remote sensing or communication or peering over the horizon types of things, or even looking up into space. There are all kinds of things and ideas out there that really provide a new value position because it’s so high. Command of the Earth below is very, very large. So, for example, the Hawk30 for telecom has a footprint of about 200-kilometer diameter, a circle 200-kilometer diameter. It’s a very big area to operate over. Obviously, depending on the payload, that can either be larger or smaller, depending on what’s needed.

So, one example of how a Hawk30 or a solar HAPS system could be deployed would be with a carrier battle group. Imagine it has its own carrier battle group satellite system dwelling overhead, providing network communications and remote observation and sensing over a very large distance. That is one example that would apply to the military.

Tyler: Just the networking ability to create an active net over the battlespace without depending on satellites, I mean you can place them anywhere. It’s just massive potential.

Steve: That’s right.

Tyler: How long can they stay up there? What sort of endurance do those craft have?

Steve: Well, what we’ve said is it’s designed to dwell for months in the stratosphere… We haven’t put a specific number on that yet. We’re in the test flight phase, the flight demonstration phase. We announced the first two successful test flights and we’ll look to announce subsequent test flights at the appropriate time.

Yeah, you could imagine the applications, the same thing could apply, let’s say there’s an operation in some part of the world where there’s not a great deal of connectivity or satellite availability overhead, simply re-deploying one of these assets over that area for the duration of that operation could be extremely helpful, whether it’s for network comms or for remote observation or other types of payloads.

Tyler: Are you seeing enhanced interest in it now that the space domain is becoming so openly contested?

Steve: Well, so I’m not in a position to speak to how… From renewed interest of space is influencing the reaction to this platform. The benefits of this platform stand alone; incremental bandwidth, remote observation, 24/7 surveillance capability, all those kinds of things are very valuable to a wide variety of customers, whether there’s a lot going on in space or not.

So we think that stratosphere is an un-tapped resource and we are aiming to be the ones to unlock that and then be able to deploy the technology in conjunction with our partners for the commercial market, and then on our own or with other partners, as the case may be, in the defense market.

Tyler: What type of altitudes are we talking about when it’s up there on station?

Steve: 65,000 feet.

Tyler: So Global Hawk territory… Definitely is a lot of line of sight up there…

Where do you see the industry heading on the defense side? Both in terms of the lower-tier end of the drone space and just in general? Where do you see things heading in this unmanned space that’s become so dominant in our everyday lives?

Steve: Well like I said earlier, it’s hard to imagine a future where unmanned systems are not ubiquitous in society. We have been able to pioneer these market segments of tactical unmanned aircraft systems, tactical missile systems, and HAPS, and we believe we’re at the very, very early stages of adoption in those. Obviously that’s the case in HAPS because we’re still in the development stage, but even with the kind of reach we’ve achieved in tactical and aircraft systems, we sell to all branches of the U.S. DOD, 45+ allied customers around the world. We currently only sell the Switchblade to the U.S. government and that’s not yet been approved for export, but we believe at some point that capability is just going be too valuable not to be almost everywhere in every military force around the world, especially because at the tactical end of it, it’s much more affordable than the much larger, much more costly systems like the one you mentioned, at the high-altitude. Not a lot of countries can afford those.

So as we introduce more capabilities, we’re constantly developing new innovative systems. We’re really fortunate to be living at the intersection of these four future lining technologies of robotics, sensors, software analytics, and connectivity, and to be able to develop these advanced solutions to integrate those and take advantage of the developments in other industries such as smartphones with batteries and sensors and software development and put those together in very robust and reliable solutions that ultimately, when a warfighter reaches into the rucksack to pull out a Raven system, they’ve gotta know it works, and their lives may very well depend on that.

So developing more capabilities that go into those systems like the ones we talked about before, whether it be enabling operations in denied airspace against great peers or delivering specific kinds of payloads to different areas, there’s going be a lot more of that in the future and we’re fortunate to be in a very sweet spot in the market to help create that reality.

Tyler: Your company is probably known best for devolving the unmanned aerial capabilities down to the individual warfighter, at least from my perspective. Do you see that becoming maybe even a larger trend in the decade that we’re in now, in the near future?… Basically what I’m saying is are we going to move further away from high-end platforms like say an F-16 that needs to hit a target with a $30,000-$40,000 laser-guided bomb in support of ground troops when you can do it with a Switchblade by a guy right there on the front line. Do you see that as the strategy going forward or where do you see your company in that area?

Steve: So you mentioned a term earlier that we use a lot to describe what our innovations have done, the democratization. In our sense, it’s democratizing the access to information and the ability to take action. So if you think about what our small unmanned systems or tactical systems like Raven and Puma, and Wasp have done, those are to, let’s say reconnaissance satellites, what smartphones are to mainframe computers, if you follow the comparison.

Mainframes were few and far between, extremely expensive, very limited in access, and someone else controlled them, just like the strategic assets. Smartphones are in your pocket, so any time of the day, if you need to find out who won the 1962 National League Playoffs, you can find that out now. Information is democratized all of a sudden. That’s precisely the way our unmanned aircraft systems are operating on the front line. If we’re a squad somewhere and we come across some obstacle and we wanna know whether we need to go right at the fork or left at the fork, we don’t have to take the chance, we don’t have to wait for some other asset to be made available that may be two hours away and the situation can change dramatically. We can simply deploy a Raven, and in a couple of minutes, we’ll know the answer and we can make the decision, and the outcomes are much better.

Similarly, if we come under fire from a sniper somewhere, we’re gonna duck and cover, and we can either call in an Apache from some base if it’s indeed available, and if it is, it’s likely not gonna be there right away, or you can send me out there and put me in harm’s way and I can just see if I can find the threat. Now with Switchblade, you can deploy it, find a threat and neutralize it before the sniper has the ability to blend into the countryside, for example.

So, that democratization of the access to situational awareness and actionable intelligence and the ability to respond quickly and accurately with a precision strike is kind of like taking an air squadron from the deck of a carrier and putting it in your rucksack, if you think about it broadly. We’re not saying for a minute that it replaces the other, but it takes airpower and puts it into the rucksack with a very tactical reach.

Similarly, integrating these systems as I described into armored personnel carriers or armored vehicles takes an air squadron and puts it on a vehicle. This air squadron is small, it is relatively low-cost compared to other air—actually fraction of the cost of other aircraft. Not anywhere near the same capabilities, but enough capability to dramatically extend what those small teams can do and how they can keep themselves safe on the frontline.

Tyler: On deploying drones from combat vehicles, are you looking at adapting to this space in any unique ways in the future, such as tailoring capabilities to urban combat?

Steve: Well, certainly, we’re very much aware that the COIN [counter insurgency] threat environment that we’ve been facing for the last 19 years will remain. That’s not going away, but in addition to that, we’ve got to be prepared for the next fight which may very well end up being against a peer or near-peer and that could very well involve more urban types of battle and operating environment.

So, definitely we are looking at that and planning for that, and investing in the development of capabilities that are going to help our forces succeed in that. I would point out that the investment piece is really important. Unlike many traditional defense companies, we invest a very, very high percentage of our revenue every year in internally funded R&D, typically between 10% and 12%, and we also tend to attract up to 20% in customer-funded R&D. So at any given time, there’s a great deal of research and development going on in our company that’s working on the capability that I’ve been talking about to address the next threat down the road.

Tyler: I think that we’re missing the human element in this discussion… A lot of times it’s the guys on the frontline that are controlling these systems. What new technology or maybe even off-the-shelf technology are you looking at or is in development to make that interface between man and unmanned system even better? Is it VR goggles, is it an Xbox controller? Is there anything new that’s coming that will help you make it even easier for a soldier to pull out a Switchblade or a Raven and put it to use?

Steve: Oh yeah, absolutely. We’re very much aware that the ground control configuration that we’ve had in place for the last 15 years is not what’s gonna be needed for the next 15 years. And we’re actively involved in defining and developing the next kind of user experience and interface that will make it easier for frontline warfighters to get any information they need or take the actions they need. Because ultimately, that’s what it’s about. We’ve gotta put as little space as possible between the warfighter and the information they need to make better decisions, or the action they need to take to preserve lives and property. And we’re currently looking at ways of doing that… Keep following us, and in the not too distant future, we’ll probably be able to talk more about that.

Tyler: Is there anything else you’d like to add that we missed, or anything else you’d like to get across to readers as far as what your company does and what’s on the horizon?

Steve: Few people may be aware of our company. It’s hard to know really. Many people I talk to are, a lot of people aren’t. But what we’ve done and the market segments we’ve pioneered and are now leading really make a difference to those warfighters. We get emails and letters all the time from people who said because of our technology, they or their comrades have been able to go home, or they avoided a very bad situation.

To be able to deal with the most cutting-edge technologies and from our engineer’s perspective, create these incredible capabilities that ultimately help save lives is really important to us. We believe that what we do is very important, we take it very seriously. We’re very proud of our role supporting the military, our military, and those of our allies.

If you think what we’ve done in the past and up-to-date is interesting, wait till you see what’s coming.

Author’s note: This interview was conducted prior to the unveiling of AeroVironment’s Quantix Rcon VTOL drone. We hope to talk a bit about that with Steve in the future. Also, a huge thanks to Steve Gitlin for his time and to Sandra Loden for setting up the exchange.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com