The U.K. government has disclosed for what appears to be the first time that it is not necessarily committed to eventually upgrading all 48 of the F-35B Joint Strike Fighters that it plans to buy with the still-in-development and increasingly costly Block 4 package. Jets without the updates would be left with more limited capabilities. This also raises questions about how existing and future F-35 operators might approach the same question.

Jeremy Quin, the U.K. Minister for Defense Procurement and member of the country’s Conservative Party, offered this note about upgrading the F-35Bs in response to a question from Kevan Jones, a member of parliament from the opposition Labor Party, on June 23, 2020. Jane’s Gareth Jennings noted the exchange in Hansard, the official record of the proceedings of both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, on Twitter.

Jones asked “whether the F-35 Block 4 upgrade is already (a) costed and (b) budgeted for in the existing F-35 programme budget for the U.K.; how many aircraft will be upgraded; and what the forecast programme cost range is.”

“The F-35 Block 4 upgrade has been included in the U.K. F-35 programme budget since its inception,” Quin responded. However, “decisions on the number of aircraft to be upgraded will be made on the basis of military capability requirements.”

The clear implication here is that while Block 4 has been a factor in the U.K. government’s budgeting around the F-35, that doesn’t mean that it plans to upgrade all 48 of the jets it expects to receive. Quin also declined to offer a figure for the total project cost of the upgrades, though Jennings noted that it has been reported to be as high as 22 million pounds – nearly $27.4 million at the rate of exchange at the time of writing – per aircraft in the past.

The Block 4 package is slated to give all three variants of the Joint Strike Fighter the ability to use the latest sensor configurations. Among the future sensors for the F-35 will be a new Raytheon Distributed Aperture System (DAS), which allows the pilot to “see” in all directions, including through the fuselage, via video feeds projected on the visor of their helmets. You can read more about this system, and the existing Northrop Grumman AN/AAQ-37 DAS, in detail in this past War Zone piece. Jennings noted that the U.K. government has already signed on to add this new DAS, itself a costly upgrade, to its F-35Bs. The aircraft’s Electro-Optical Targeting System (EOTS), which is based on out of date mid-2000s technology, will also be upgraded, among other sensor enhancements.

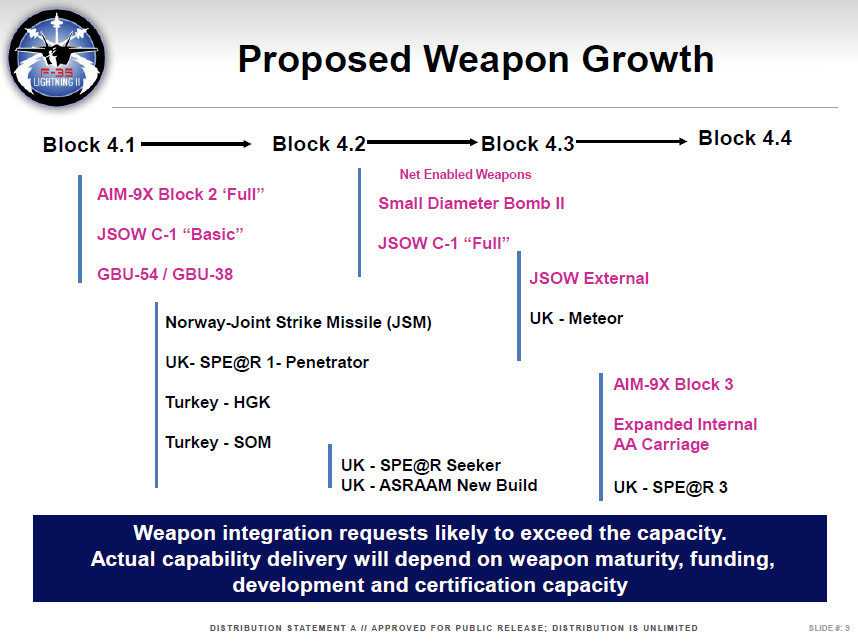

The Block 4 updates will also include the integration of new weaponry, such as the GBU-53/B StormBreaker precision-guided bomb and the SPEAR 3 miniature cruise missile, the latter of which is a U.K.-specific requirement. Some weapons that had been slated to come along with the Block 4 package are already being integrated, such as the AGM-154 Joint Stand-Off Weapon (JSOW). It’s also worth noting that earlier this month, in response to a Freedom of information request, the U.K. government revealed that it has no plans to buy any 25mm gun pods for its F-35Bs.

Regardless of what the package will or won’t include, the development of the Block 4 updates has been mired in delays and cost increases for some time now. In 2019, the Pentagon told Congress that the total estimated lifecycle costs of U.S. military F-35s had gone up by $22 billion entirely due to Block 4. At that time, the Pentagon said it expected to spend $1.196 trillion on operating and sustaining Joint Strike Fighters across the Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps through 2070.

The year before, the F-35 Joint Program Office had announced plans to try to begin adding some Block 4 capabilities on a rolling basis as part of a concept known as Continuous Capability Development and Delivery (C2D2). It had already presented the possibility of breaking the upgrade package in four separate smaller updates referred to as Blocks 4.1, 4.2, 4.3, and 4.4.

A concept called “concurrency” has long imposed a variety of costs on the F-35 program from the very beginning. Under this plan, Lockheed Martin began actually building Joint Strike Fighters knowing full well that there would be a need to insert fixes and modifications over time, albeit the scale and scope of those rework requirements were grossly underestimated. The idea, in theory, was that this was supposed to reduce costs by ramping up production earlier than normal.

In practice, the decision drove up costs, created schedule delays, and has created a need for costly fixes and updates. Just today, Defense News reported that Lockheed Martin had disclosed a new issue with the Onboard Inert Gas Generation Systems (OIGGS) on U.S. Air Force F-35As, saying that it “appears this anomaly is occurring in the field after aircraft delivery,” which could point to the need for a new fix of some kind. The OIGGS fills empty space within the aircraft’s fuel tanks with nitrogen-enriched air, mitigating the risk that an aircraft suffering a lightning strike on the ground or in the air could experience a catastrophic explosion. This is a long-standing issue that you can read about in more detail in this past War Zone piece.

The rolling nature of these required reworks has also created a situation wherein there are many sub-configurations within the young fleet of F-35s, creating additional difficulties for both operating and maintaining the jets. Some of the earliest U.S. military examples are simply not fully combat capable and have been relegated to training and test and evaluation roles.

The long-troubled Autonomic Logistics Information System, or ALIS, a cloud-based computer system that handles a host of maintenance and operational planning tasks, which you can read about in more detail in this past War Zone piece and is now set to be replaced, struggles with this reality. The continuing issuing of spare parts that simply don’t work on certain aircraft and the misdiagnosis of problems contributes substantially to high sustainment costs and low readiness rates.

While F-35 operators outside of the United States, such as the United Kingdom, which received their aircraft later on, or have yet to even take delivery of their first examples, have escaped some of the worst impacts of concurrency, the Block 4 upgrade presents a new additional sustainment cost issue. Even if much of the research and development work has been paid for already, the remaining costs to actually update the jets will still be high. Certain modifications are especially cost-intensive given how hard it is to upgrade the aircraft’s physical structure due to its fixed mold-line built and the high-level of integrated across its systems.

If the U.K. government does expect the unit cost of the upgrade package to be around $27.4 million, that would amount to increasing the purchase price of the jets by roughly a quarter or more. There have already been questions about whether there might be cuts to the planned British F-35 fleet in the face of other budget uncertainty in recent years.

Other existing F-35 operators will have to make similar choices about the costs and benefits of upgrading their jets when the Block 4 package arrives. Even the newest Joint Strike Fighter customers, such as Poland, which expects to receive its first examples in 2024, could be impacted. As of 2019, the Joint Program Office’s timeline for Block 4 had the very first production aircraft with the upgrades getting delivered in the 2023 Fiscal Year.

That is all dependent on the development of the upgrade package proceeding as planned and getting delivered in full by that time. Aircraft delivered with some form of interim Block 4 update could still need updates depending on the operator’s exact requirements and the state of the upgrade package at the time of rolling off of the assembly line.

Joint Strike Fighter operators could certainly use aircraft without the upgrades for training or test and evaluation roles, just as the branches of the U.S. military have done with their older aircraft. However, for smaller operators, relegating some of the handful of jets they have to primarily non-combat missions would reduce the overall combat capacity of their F-35 fleets and would result in mismatched fleet management.

All told, the U.K. government’s ambiguous statement about whether or not it will upgrade all of its F-35Bs with the Block 4 package only further underscores the difficulties and growing costs that Joint Strike Fighter operators will continue to have to mitigate and defray as time goes on in order to get the most out of their F-35 fleets.

There is no doubt that the Block 4 enhancements are extremely important to helping the F-35 realize its full potential, but they are going to come at a hefty cost that some operators may not be willing to bear.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com