Japanese Defense Minister Taro Kono has publicly announced a decision to suspend the establishment of two Aegis Ashore missile defense systems in the country indefinitely. Kono cited technical issues and rising costs as the main factors, but there has been significant domestic opposition to the program, which already forced Japanese authorities to abandon plans to deploy one of the missile defense systems at a site in the country’s northeastern Akita Prefecture.

Japan’s top defense official informed members of the press about the shift in the country’s missile defense plans on June 15, 2020. Kono said he had told Prime Minister Shinzo Abe about the decision on June 12. The Japanese government finalized their initial plans to set up the two Aegis Ashore sites back in December 2017. The U.S. government formally approved the sale of the missile defense systems, as well as ancillary items and support services, a complete package valued at around $2.15 billion, in January 2019. Japan had already pushed back the date it hoped to have both Aegis Ashore systems up and running from 2023 to 2025.

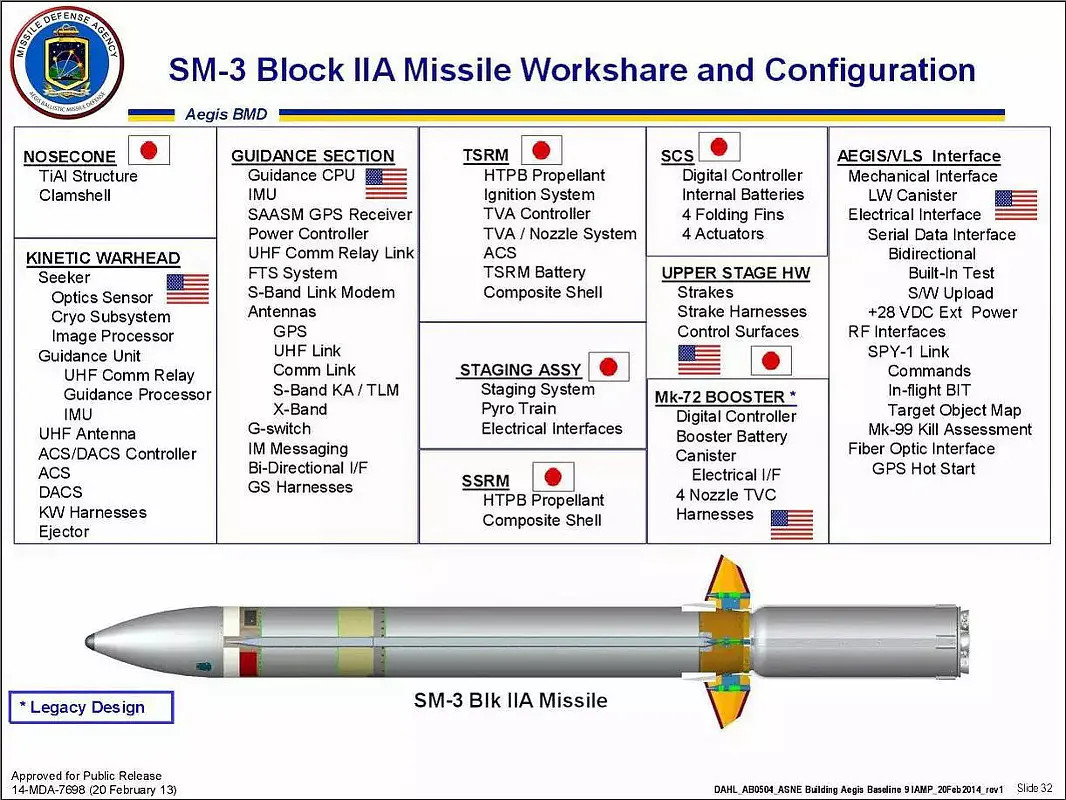

Kono blamed technical issues, and the costs to rectify them, as the primary reasons behind the suspension of the Aegis Ashore plans. The main issue, he explained, was ensuring that the rocket booster from the SM-3 missile interceptors that are the system’s primary armament would fall away from the rest of the interceptor and not hit populated areas down below. The Japanese Defense Minister said that attempts to modify the software in these weapons to make sure the debris only lands in designated areas has been unsuccessful so far.

This promises to be an issue for all SM-3 variants, including the still-in-development Block IIA version, which the Japanese government has been working on together with the United States for years now. Japan has spent approximately $1.02 billion of its own money on that project, which you can read more about in this past War Zone piece. The Block IIA is designed to offer significantly expanded capabilities against larger missiles over earlier versions of the SM-3, all of which are intended to engage ballistic missile threats flying outside the Earth’s atmosphere during the midcourse portion of their flight. The Aegis Ashore sites also have the potential to be able to launch other missiles, such as the increasingly capable SM-6 missile series, in the future, as well.

The Japanese Defense Minister’s explanation, however, inherently underscored the significant pushback that the country’s authorities have faced over the Aegis Ashore plans since they were first announced two and a half years ago. There has been significant public concern about the potential health impacts from the radiation from the Aegis Ashore system’s powerful radars. Japan’s sites are set to use Lockheed Martin’s Long Range Discrimination Radar (LRDR) in place of the AN/SPY-1 that the U.S. Navy presently employs in its version of the system.

On top of that, in June 2019, Japanese officials had to make the embarrassing admission that they had picked one of the two planned Aegis Ashore sites, the Araya Maneuver Area in Akita Prefecture, based on miscalculated terrain data from Google Earth. Japan’s Ministry of Defense agreed to redo 20 geographical surveys to reassess whether Araya was indeed the best option, and hoped to have the results ready by March.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic has repeatedly pushed that schedule back and authorities announced that they had formally abandoned plans to use the site in Akita without choosing a substitute in May. Domestic opposition had also been building in communities near the other proposed site situated in the country’s southwestern Yamaguchi Prefecture.

“For the time being, we’ll maintain our capability of missile defense by Aegis-equipped destroyers,” Kono said. At present, the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) has seven guided-missile destroyers across three classes with the Aegis combat system that are capable of firing SM-3 variants, which represents a key component of the country’s current ballistic missile capabilities. This includes the advanced JS Maya, the first of two planned so-called 27DDG destroyers, which the JMSDF commissioned in March and that you can read more about in depth in this past War Zone piece. These ships are also set to receive the advanced SM-3 Block IIA interceptors.

The Japan Air Self Defense Force (JASDF) also operates a number of Patriot surface-to-air missile system batteries, as well, a number of which are now capable of launching the newest PAC-3 Missile Segment Enhancement (MSE) interceptors. However, these systems still have a far more limited terminal phase ballistic missile defense capability compared to the mid-course intercept capabilities of the existing Aegis destroyers and planned Aegis Ashore sites.

The Aegis Ashore sites were supposed to provide Japan with an additional layer of defense against potential threats, especially from North Korea’s ballistic missile arsenal, which has been steadily growing in size and scope in recent years. The North Koreans, who have recently begun making worryingly provocative threats against South Korea and have shut down formal lines of communication after years of thawing relations between the two sides, have test first missiles over Japan’s home islands, as well as near Japanese territorial waters, on multiple occasions in the past.

There were also expected to expand the country’s general regional missile defense capabilities. Friction between Japanese and Chinese officials over long-standing territorial despites, particularly surrounding the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea, which Japan controls, has been growing in recent years. The Senkakus are more than 550 miles southwest of Japan’s home islands, but are less than 250 miles east from the Chinese mainland.

Japan’s Aegis Ashore sites were also set to be heavily integrated with the U.S. military’s own ballistic missile defense assets in the country and the overall American ballistic missile defense infrastructure around the world. A new delay in the Japanese government schedule for setting these sites up, or if authorities in Tokyo decide to give up on the effort entirely, could also limit the defenses available to U.S. forces in the country and elsewhere in the region during a major contingency.

Regardless, for now, Japan has halted its Aegis Ashore missile defense plans. With no sign that domestic opposition to the establishment of the two sites is waning, it very much remains to be seen how the Japanese government will now decide to proceed with the project in the future.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com