The F-117 Nighthawk continues to capture the public’s imagination well over a decade after it was officially retired. Even though it flies on in a limited fashion for testing and training purposes, its days as a combat aircraft are long behind it. While it was best known for snaking its way through enemy air defenses to strike fixed targets with pinpoint precision using conventional laser-guided bombs, the truth is the ‘Black Jet’ was fully equipped to deliver far more devastating weaponry if the balloon went up during the twilight of the Cold War.

Originally, the Senior Trend program that gave birth to the F-117 included the goal of having the aircraft be able to carry the majority of the weapons the Air Force had to offer for its tactical fighter and attack aircraft at the time—the 1970s. The realization of the jet’s limitations and strengths paired down its operational weapons menu considerably. Still, all the cockpit interfaces and diverse stores management capabilities were baked into the design—including the provision to carry and employ nuclear gravity bombs—namely the B57 and B61 (shown front and center in banner image).

The F-117s cockpit included an Aircraft Monitoring And Control (AMAC) panel that interfaced with the Permissive Action Link (PAL) on the nuclear weapons that allowed them to be armed and programmed prior to delivery. This hard-wired nuclear capability lasted throughout the F-117’s entire career, and, at least for a time, it wasn’t just something the Air Force largely forgot about.

At first glance, the F-117 would have been a terrifying nuclear delivery platform for the Soviets to contend with. It was built to penetrate dense enemy air defenses via a cocktail of measures. Shaping, which accounted for roughly 75 percent of the aircraft’s radar cross-section reduction, and radar-absorbent materials and coatings, which made up the rest, are the aircraft’s most known and innovative traits, but its mission planning software, which was state-of-the-art at the time, was also extremely important when it came to the plane’s enhanced survivability.

The F-117’s route was meticulously planned before each strike mission, with the latest electronic and other intelligence on enemy air defense threats and overall force posture factored into its every pre-planned move. Even the angle at which the F-117 presented itself to known threatening emitters was part of the computerized planning process that aimed to give the F-117 pilot the best shot at surviving based on all known factors. As such, when taking on the Russian Bear’s deeply entrenched air defenses in Eastern Europe, the F-117s chances of making it to its target would likely have far eclipsed that other tactical jets in the Air Force’s inventory at the time.

Beyond these finite details, it was a stealth attack plane the likes of which the world had never seen. It represented an almost magic-like technology at the time. Without knowing its Achilles heels, it would likely have seemed invincible to Moscow. But using the stealth jets poised to strike on the front lines of the Cold War as a nuclear deterrent wasn’t meant to be.

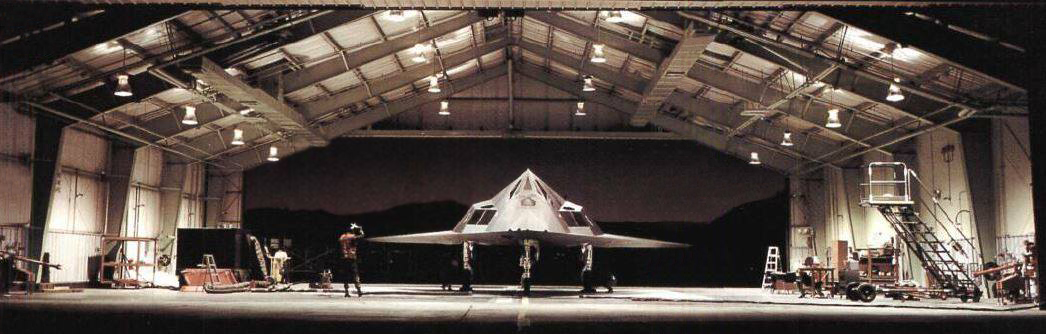

During the mid-1980s, as the F-117 program morphed from a development and testing effort to also an operational one, the idea of forward-deploying groups of F-117s to stand nuclear alert in the United Kingdom and even South Korea were examined. The main issue with doing so was the fact that the aircraft was one of America’s most closely guarded secrets, so extending operations to two points around the globe on any scale could have resulted in the aircraft’s existence, and even its configuration and its general capabilities, to be known. Also consider that during this time the aircraft was such a tightly held secret that it lived at a remote, extremely high-security airfield in Southern Nevada and only came out at night. All of the sudden pushing the F-117 overseas, even in small groups, would have negated all the work that had been done and continued to be done to keep it secret.

Just the unique infrastructure the F-117s required for prolonged large-scale operations would have made such an idea highly unattainable on a security level, not to mention it being an expensive proposition, to say the least. For so few aircraft, only 59 F-117As were built, and considering it could carry just two bombs, the trade-off in secrecy and cost against the impact they would have on a sudden nuclear exchange just didn’t balance.

So, saving contingency operations, the F-117 would not serve in the nuclear alert role in any standardized fashion, at least while its existence remained highly classified.

That didn’t mean that the nuclear strike mission was abandoned. Instead, operational F-117s units were well aware of the jet’s latent nuclear capability and their regular precision strike training that included infiltrating deep into enemy airspace also prepared pilots for the nuclear mission, in at least a tertiary fashion. If there was a crisis that would have required the F-117’s presence in a nuclear weapons delivery role, regardless of if it compromised the veil of secrecy surrounding it at the time, crews would have been able to spin up quickly for the unique mission and execute it if need be.

The F-117 test enterprise, which was extremely active alongside the operational elements of the program throughout the aircraft’s early operational days to its retirement, worked at validating various deployment profiles of at least the B61 tactical nuclear bomb throughout the 1980s. It isn’t exactly clear just how diverse a set of tactics and procedures they validated, but it’s safe to say that by the end of the Cold War and beyond, the jet’s nuclear weapons delivery capability became more proven. This also points to the reality that the test team could have ramped up nuclear weapons delivery trials and refined existing procedures further in short order if geopolitical events required them to do so even early on in the jet’s active-service career.

One example of the ongoing nuclear delivery profile expansion testing lies in an incident with a test F-117 flying out of Groom Lake in 1985. The aircraft had a major malfunction with its v-tail section during the test flight that included at least in part, a weapons compatibility objective. While the weapon was hanging out in the slipstream during a maneuver, the aircraft began to shake violently. The pilot was able to recover safely and the issue was quickly fixed, but the weapons integration test the program was executing during that flight was for a delivery profile—supposedly a toss from medium altitude—with a dummy B61 nuclear bomb.

Veteran F-117 pilot Robert “Robson” Donaldson, Bandit #321, recently appeared on the Fighter Pilot Podcast, in which a very brief mention of the F-117’s secondary nuclear mission was made, prompting our investigation. You should give the segment a listen here. We got in contact with Donaldson through our friends at the Fighter Pilot Podcast to learn more about his experience with the Nighthawk and the plane’s very seldom discussed nuclear role. Considering he flew the jet at the very tail end of the Cold War, from 1989-1992, just as the aircraft was really maturing on an operational level and at the very end of its deep ‘in the black’ existence, he would certainly be able to clarify the off-hand mention in the podcast.

Donaldson told The War Zone that they never really practiced heavily for the mission, but it was always looming in the background. If the jets were needed in a crisis, they were prepared to deploy to the United Kingdom where they would prosecute targets in Eastern Europe. He remembers having to fully memorize the mission to hit his assigned target, which was in Rostock, East Germany, and he was tested on it in front of other officers in the unit to make sure he was fully up to speed should the call come. This was apparently a common experience across the active F-117 pilot corps at the time. His preparation for this mission was for a conventional weapons delivery—GBU-27 laser-guided bombs—but the idea of sudden snap deployment to hit targets in Eastern Europe could have ported over to the nuclear mission, as well.

Donaldson also notes that if the aircraft were to have exercised its nuclear weapons employment capability, it would have likely used the laydown method of delivery nuclear bomb delivery profile to maximize its stealthiness and survivability. This is where the aircraft zooms overhead the target and drops a retarded nuclear bomb, which would use a parachute to slow its descent to the ground, in some cases lying in the target area for a short moment in time before detonating. This allows the aircraft to get away without being caught in the nuclear weapon’s powerful shockwave. Using this method would have allowed the F-117 to maintain a relatively conservative attitude along a very carefully planned path while also minimizing the time the jet’s bay doors are open, which balloons its small radar signature.

As we just mentioned, the F-117s could have been used in the non-nuclear role during World War III, as well, knocking out key infrastructure and defenses in the opening days of a conflict. Its limited range would have curtailed just how far it could have struck into the USSR and operating over an active nuclear battlefield in an aircraft no more hardened for the nuclear combat environment than any Tactical Air Command fighter of the era, may have also been issue as the conflict matured. The question of what basing and tanker support would even have been left by the time the F-117s mobilized overseas makes their involvement in any form of World War Three, aside from the opening punches if they were forward deployed in advanced, fairly questionable.

The F-117 crept out of the darkness just as the Cold War and the 1980s were ending. Forward deploying the jets even while the program was still largely under wraps was tested successfully following the aircraft’s combat debut in Panama in 1989. The F-117s recovered at England AFB in Louisiana after the mission, a detail that wasn’t disclosed until many years after the mission took place.

The F-117s executed a true test deployment, also to England Air Force Base, under far less secrecy in 1990, which really paved the way for future expeditionary operations. So, even with some of the secrecy and security restrictions having been relaxed, the question of if the world’s first stealth combat aircraft would be folded into NATO’s larger nuclear strategy on a consistent basis would never be answered, and thankfully so.

While the F-117 could and did deploy overseas with some regularity after its declassification, with the threat from Russia diminished and other hotspots taking the spotlight, the notion of sending the F-117s on some sort of standing nuclear alert eroded even further. The B-2 Spirit had also transformed from dream to a flying reality in this same period and that aircraft, which was totally optimized to the deep nuclear strike mission, provided the U.S. with a penetrating stealth bomber with a huge weapons load that could duke it out with a major power during the apocalypse. The introduction of the AGM-129 stealth cruise missile into service in 1990 also made the F-117’s latent nuclear capabilities even more redundant.

So, all said, you can think of the F-117’s nuclear capability as very real, but it was kept largely in reserve during the Cold War. The jet’s extreme secrecy kept it from actively deterring the unthinkable, but if a major crisis in which there was time spin-up and push some of the Nighthawks to the frontline had occurred, they could have been ready to weave their way through enemy air defenses beyond the Iron Curtain and even over of the Demilitarized Zone that bisects North and South Korea, if called upon.

As for the F-117’s nuclear capability long after the Cold War ended—it never fully melted away, although by the end of the Gulf War the Nighthawk had been crowned America’s silver bullet precision conventional strike superweapon and further refining that capability would continue to be the program’s focus till its official retirement in 2008.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com