China has made massive investments in modernizing its military over the better part of the past three decades and has established new and improved research and development and training bases to support those efforts. The People’s Liberation Army has fully embraced the idea of utilizing highly realistic facilities to prepare its forces for the sorts of environments they’d be likely to fight in during future conflicts, drawing significant lessons from the experiences of the U.S. military and those of its allies. The Zhurihe Training Base in remote Inner Mongolia is the largest of these sites and notably features a huge full-size mockup a portion of downtown Taipei, the capital of the island of Taiwan, including highly elaborate recreations of its Presidential Office Building and Ministry of Foreign Affairs. There’s also a cloverleaf highway interchange, a mock airfield and, bizarrely, a replica of France’s Eiffel Tower.

Zhurihe, also known as the Zhurihe Combined Tactics Training Base, is China’s largest training base by physical size. Observers have compared it, together with its adjacent training ranges, to the U.S. Army’s Fort Irwin in southern California and that base’s associated sprawling National Training Center (NTC). The NTC is home to a large number of diverse facilities that also give the Army room to conduct large scale unit exercises covering a wide variety of combat scenarios. As with the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment at the NTC, Zhurihe also has its own dedicated units to play the role of enemy forces during drills. These are known as the “Blue Army,” a play on the Western term “Red Force” to refer to Opposing Forces during exercises.

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) first established Zhurihe in 1957, primarily as a tank training base. Four decades later, Chinese authorities decided to transform it into a multi-functional “first-class” facility that would prepare its forces for “hi-tech battles” of the future.

China’s military leaders had closely watched the U.S. military lightning victory over Iraq during the First Gulf War in 1991 and already started to question the adequacy of the equipping and training of their own units. In 1996, then-U.S. President Bill Clinton’s sent a pair of carrier strike groups to sail through the Taiwan Strait in response to a major crisis between authorities in Beijing and on the island, which is seen as a critical event that contributed to China’s subsequent decision to initiate a massive military modernization effort across the board, which included the expansion of Zhurihe.

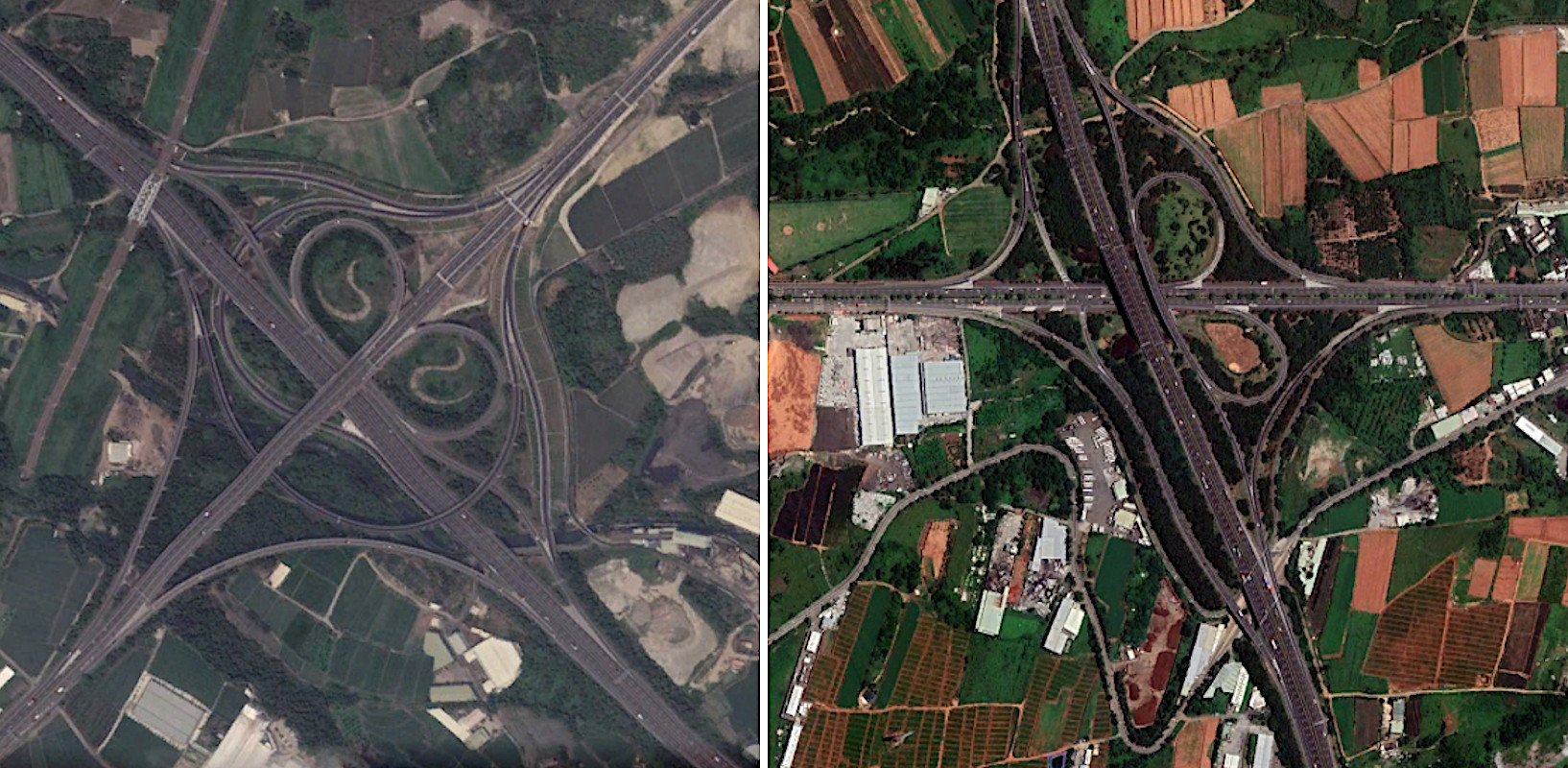

By the mid-2000s, Zhurihe’s facilities had significantly expanded in size and scope, with a heavy emphasis on features that would be used to prepare forces for what the U.S. military calls Military Operations in Urban Terrain (MOUT). By the end of 2014, it had further grown to include the Taiwan-related structures, as well as other features to support larger exercises, including an associated operational air base with a more than 9,000-foot-long runway to the northwest and a huge railhead to allow the rapid movement of vehicles, heavy weapons, other equipment, and personnel to and from the site. All of this is visible in high-resolution satellite imagery of the area that The War Zone recently obtained.

You can view the full high-resolution satellite images that The War Zone obtained by clicking here. The one below has been downsized to give an overview of the base for this article.

Zhurihe’s main administrative center, which includes a full military hospital and barracks facilities, is at the northern end of the base. This is one of a number of areas that have seen substantial expansion over the past two decades.

It’s interesting to note that there are no less than 20 basketball courts near the barracks. Despite its Western origins, the Chinese Communist Party, and the People’s Liberation Army, in particular, have actively promoted basketball for decades, with the popularity of the sport notably surviving the Cultural Revolution. As a result, Chinese military bases are curiously easy to identify by the presence of basketball courts.

The railhead runs along the eastern edge of the base. It features a large reception building with a blue-topped awning over a large portion of the platform right in front of it. In China, as in many places around the world, trains remain a critical method for moving heavily military vehicles and other equipment around both for exercises and operational purposes.

The associated operational air base, situated some seven miles northwest of Zhurihe’s administrative center, has also seen significant expansion over the years. At present, it has the aforementioned 9,000-foot main runway, as well as 28 separate helipads and numerous hangars. It also has six more basketball courts in its own not insubstantial administrative and barracks area.

Construction of this air base was in its early stages in 2011 and was still ongoing in 2013. Between the hangars, the helipads, and the space on the base’s apron, there is a lot of room for tactical aircraft and helicopters to support fully integrated combined-armed training.

Also to the northwest of Zhurihe’s main base, with its own dedicated access road, is an extremely heavily fortified compound encapsulated by four separate fences and walls with watchtowers at its corners. It’s not clear what this facility’s purpose is, but most of the structures inside appear to have garages, meaning it could be used to store particularly sensitive vehicles, such as transporter erector launchers for ballistic missiles. It might also serve as storage for equally important weapons, such as nuclear warheads. Alternatively, it almost has the look of a military prison or a place where very important officials could flee to in a crisis.

Zhurihe’s most interesting, unique, and curious features are found at the southern end of the base. This is where the huge full-size realistic urban training areas, as well as a mock air base, are situated.

The Tapei section is one of the most elaborate urban training areas that we here at The War Zone are aware of. By itself, the recreation of the Presidential Office Building, a structure that is some five-stories tall with six-story high corners and a large central tower nearly 200 feet tall, is likely the largest of its kind anywhere in the world.

Beyond its functional purpose, Taiwan’s Presidential Office Building also holds important historical significant force both the island and mainland. Japanese colonial authorities built it between 1912 and 1919 and severely damaged during World War II. It was restored under Nationalist rule between 1947 and 1948. Between then and 2006, it was also referred to as Chieh Shou Hall, which Chieh Shou translating to “Long live Chiang Kai-shek,” in reference to the long-time Nationalist leader.

In many ways, the structure reflects the island’s continued de facto independence from the mainland and its general history of it being outside of Beijing’s control. As such, it’s hard not to interpret the mock structure at Zhurihe as a particularly ominous sign of the Chinese government’s intentions to bring Taiwan back into its orbit. Taking control of Taiwan’s seat of power during an actual invasion would certainly be a top priority. The fact that China has invested heavily in actually trains on doing so against a full-scale mockup is quite troubling, although such a practice isn’t unheard of. North Korea has a full-scale replica of South Korea’s Blue House that it trains on.

Further to the south, beyond Zhurihe’s Taiwan-related structures, is a mock air base, the initial iteration of which was completed between 2013 and 2014. At that time, it had a runway around 3,900 feet long and two separate aprons, as well as various small structures. In 2017, extensions were made the runway at both ends, bringing it to around 10,105 feet. Gates are now in place that can close off these additions from the main portion of the runway and there are a number of more austere aprons along the northern end.

This simulated air base would be a very valuable asset to have in order to help People’s Liberation Army units train to assault and seize control of enemy airfields. There are also three medium-size helicopters, two twin-engine turboprop transports, a single four-engine turboprop transport, and an airliner type jet aircraft to provide added realism. Some of these aircraft, especially the airliner, could provide space for specialized units to train to respond to hijacking and VIP protection scenarios, as well. The extended runway also means that the People’s Liberation Army Air Force could land larger aircraft, such as the Y-20 airlifter, directly at this site for training purposes and fly in newer and bigger planes to use as training hulks.

By far the most curious and still largely unexplained structure at Zhurihe is a metal tower that, by every indication, is a sub-scale scale replica of the Eiffel Tower in France. Constructed sometime around 2010, it predates the Taipei section and the mock airstrip.

The tower could be in use as a structure to support antennas or aerials and would offer a good field of view for line-of-sight communications in the area. The satellite imagery from February shows what appears to be a large wire linked to an upper section that could provide a hard link between it and a nearby structure.

It also appears to serve as an elevated view platform for commanders, Chinese VIPs, and dignitaries from foreign militaries observing exercises at Zhurihe. There appears to be four major platforms at different heights on the tower. It could even be used as a training aid for scaling large lattice structures.

The video below includes a brief clip at around the 1:22 mark in the runtime showing whats appears to be People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) transporter-erector-launchers for the DF-16 short-range ballistic missile driving under the tower at Zhurihe.

Interestingly, this isn’t the only Eiffel Tower replica in China, either. There is another one in Tianducheng, China, a suburb of Hangzhou in the country’s Zhejiang Province, which has an overall aesthetic meant to evoke the architecture in the French capital Paris. There is another recreation of the Eiffel Tower at the Window of the World theme park in the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen, situated on the mainland just outside Hong Kong.

Both of these structures predate the construction of the tower at Zhurihe, so there is also a possibility there might have been some desire to create a representative tower for training purposes, such as to prepare specialized military and police units for a domestic terrorism scenario at either location. Still, the exact motivation behind the design of the structure isn’t clear, but what is clear is that China likes to make replicas of iconic structures.

It’s also worth noting that Zhurihe isn’t the only place where the People’s Liberation Army has built realistic approximations of potential enemy facilities to train on. In 2006, it emerged that the Chinese military had built a full-size air base in the country’s northwestern Gansu Province modeled after Taiwan’s Ching Chuan Kang Air Base at Taichung airport to serve as a bombing target for the People’s Liberation Army Air Force.

In the first half of the 2010s, the People’s Liberation Army also built a host of large-scale simulated targets in the Gobi Desert for its rocket forces to fire ballistic missiles at during training and testing. These sites included mock airfields, hardened aircraft shelters, piers, and even the outlines of large warships, some of which appeared to mimic American facilities and assets at various bases in Japan.

The construction of the Taipei section at Zhurihe and the targets in the Gobi came around when the Chinese government under President Xi Jinping was beginning to show signs of a more aggressive foreign policy, especially with regards to the country’s claims over the bulk of the South China Sea. That remains a major point of contention between Beijing and other countries in that region, as well as much of the international community, including the United States, in particular.

In addition, in late 2014, Taiwan’s Democratic Progressive Party, which has promoted the idea of declaring full independence from the mainland, also won a landslide victory in local elections. In July 2015, Chinese state television broadcast a segment, part of which is seen below, that briefly showed troops assaulting mock Presidential Office Building at Zhurihe, which was widely seen as a signal to Taiwanese officials.

In 2016, Tsai Ing Wen, then head of the DPP, won Taiwan’s presidency, which has led to steadily escalating tensions between authorities on the island and the mainland. Officials in Beijing had branded Tsai an “independence extremist” and have repeatedly threatened military action should authorities in Taipei attempt to formally break away from the rest of China. She has also cultivated a very close relationship with President Donald Trump and his administration, securing unprecedented arms deals, including for new Block 70 F-16C/D fighter jets.

One has to wonder whether we might soon see new activity at Zhurihe’s Taipei section as friction between Beijing and Taipei has flared even more significantly since Tsai won a second term in January. Last week she announced plans for “constitutional amendments” that might indicate a new push toward formal independence. Chinese authorities have, unsurprisingly, condemned the moves.

“We will not accept the Beijing authorities’ use of ‘one country, two systems’ to downgrade Taiwan and undermine the cross-strait status quo,” Tsai said in a speech at her inauguration on May 20, 2020. “This democratic process [of constitutional amendments] will enable the constitutional system to progress with the times and align with the values of Taiwanese society.”

“We will show no tolerance for any secessionist act and foreign interference,” Ma Xiaoguang, the spokesperson for the People’s Republic of China’s Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council, said that same day in response. “The DPP … has unilaterally destroyed the political foundation for peaceful development between the Chinese mainland and Taiwan. … National reunification is inevitable as the Chinese nation marches toward its great rejuvenation and cannot be stopped by anyone or any force.”

Though the general language of these threats is hardly new, there are concerns that more serious confrontation could be in the offing, especially given months of more tense interactions between Chinese and Taiwanese military aircraft and ships. In addition, Beijing has been more actively working to wedge Taiwanese officials out of international organizations, especially in regards to the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Chinese government appears to be using the current state of affairs around the world, where most of its primary opponents, such as the United States, are focused heavily on battling COVID-19, to pursue aggressive foreign policy activities elsewhere, too. Officials in Beijing are looking to enact a new national security law that would effectively strip Hong Kong’s unique semi-autonomous status. The enclave has already seen months of on-and-off-again protests in response to previous efforts to curtail certain freedoms in the past year or so.

China has triggered an unprecedented standoff along its border with India, ostensibly in response to Indian military construction, with unconfirmed reports that thousands of Chinese troops may now be encamped in Indian territory, as well. The Indian government has downplayed that highly fluid situation, saying that they are pursuing a peaceful resolution via official channels. A similar situation in that region in 2017 did ultimately end following diplomatic efforts between the two countries.

All told, the Chinese government under Xi appears to be entering the 2020s more assertive than ever in response to threats and challenges, real and perceived, domestic and foreign. This can only increase the emphasis within the People’s Liberation Army on staying prepared for major conflicts and other contingencies.

As such, Zhurihe will remain an essential training area, if not become more important, given its array of unique and specialized mock facilities, especially those related to Taiwan.

Zhurihe has, understandably, been a topic of interest for many years now. Here are some additional links to other earlier overviews and analysis that we referred to while researching this story.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com