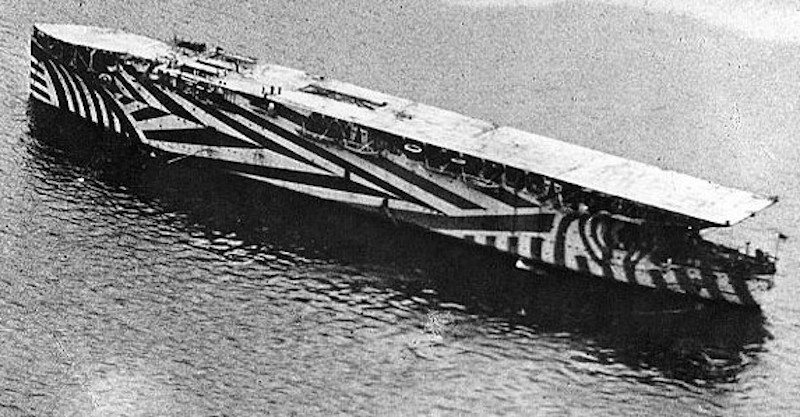

Air forces around the world will often give their aircraft specialized paint jobs to commemorate anniversaries and other notable occasions, but it’s far less common to see navies do the same thing with their ships. Recently, however, the Royal Canadian Navy’s Halifax class frigate HMCS Regina recently took part in a training exercise wearing an iconic blue, black, and gray paint job, commonly known as a “dazzle” scheme, a kind of warship camouflage that first appeared during World War I.

At the end of March 2020, Regina, and her unique paint job, had joined HMCS Calgary, another Halifax class frigate, along with the Kingston class coastal defense vessel HMCS Brandon and two Orca class Patrol Craft Training (PCT) vessels, Cougar and Wolf, for Task Group Exercise 20-1 (TGEX 20-1) off the coast of Vancouver Island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean. The training continued into the first week of April. TGEX 20-1 was part of Calgary‘s Directed Sea Readiness Training (DSRT) in preparation for that particular ship’s upcoming deployment.

Regina had first emerged in the dazzle scheme in October 2019 ahead of the U.S. Navy-led Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise, a massive naval training event that takes place every two years and includes U.S. allies and partners from around the Pacific region. It reportedly took 272 gallons of paint and cost the Royal Canadian Navy $20,000 to give Regina the dazzle treatment.

The frigate will wear the camouflage pattern until the end of 2020. The Royal Canadian Navy also painted up the Kingston class HMCS Moncton, which is homeported in Halifax on the other side of the country, in a similar scheme. The paint job on both ships is in commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the end of the Battle of the Atlantic. This refers to the Allied fight to both enforce a naval blockade of Germany during World War II and secure critical maritime supply routes from North America to Europe. The battle officially ended with the surrender of the Nazi regime in May 1945.

In this context, the paint scheme has significant for both Regina and Moncton. The first Royal Canadian Navy ships to carry these names were both Flower class corvettes that fought in the Battle of the Atlantic. Moncton conducted convoy escort operations between 1942 and 1944, before being transferred to the Pacific Theater. Regina also protected allied merchant vessels making the cross from 1942 to 1944, when she was unfortunately sunk by the German U-boat U-667 off the coast of the United Kingdom. She succumbed to the seas in less than 30 seconds and 30 of her 85 crew members died.

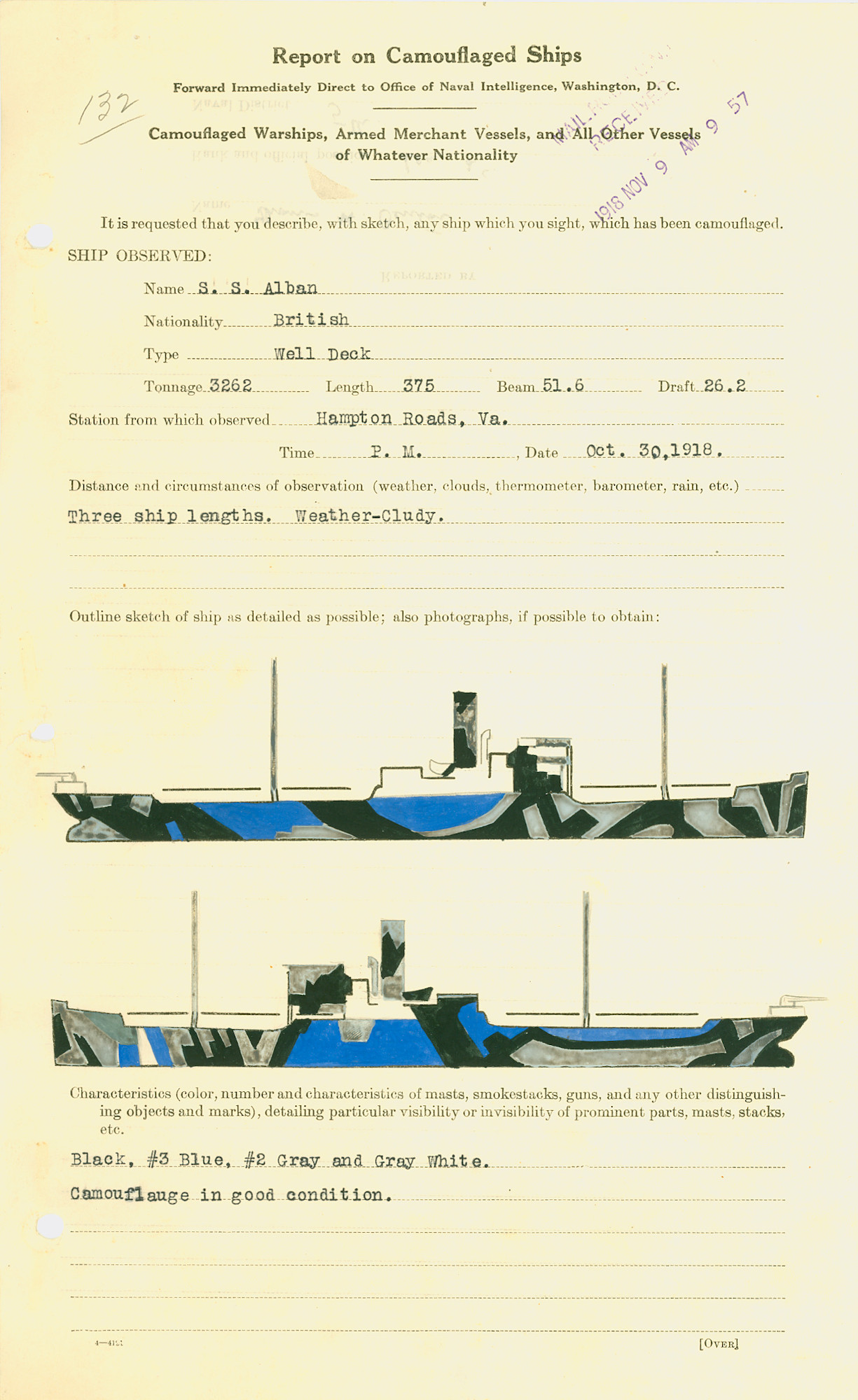

Despite the commemorative nature of the paint schemes, dazzle and other disruptive naval camouflage patterns date back to World War I. British artist Norman Wilkinson, primarily known for maritime paintings, is credited with inventing the dazzle concept, which consisted of angular patterns applied to a ship’s hull and superstructure intermittently. White and black were the most common colors, but some patterns included blue and gray, just like the commemorative ones that Regina and Moncton are wearing right now.

In 1917, Wilkinson, who was then a Royal Navy Lieutenant Commander, proposed his camouflage idea in response to Imperial Germany’s successful unrestricted submarine warfare against Allied shipping in the Atlantic. The idea was that that paint scheme would make it difficult for German submarine crews to effectively gauge the distance, heading, and speed of ships on the surface, making it more difficult for them to position themselves for an attack and increase the opportunities for friendly forces to the detect them. The same general principles applied, at least in theory, to surface engagements, especially at long ranges, given the relatively limited capability of optical sighting systems at the time. The British Army also experimented with similar disruptive schemes on motorized vehicles and its tanks, a then-new type of weapon that the service was first to introduce on the battlefield.

While dazzle is commonly used today as a catchall term for a number of disruptive naval camouflage schemes, at the time, it technically only refers to the patterns that came out of a special unit that the Admiralty in the United Kingdom had set up late in World War I with Wilkinson at its head. Between 1914 and 1915, the Royal Navy, at the direction of then-First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, had experimented with more fluid disruptive schemes employing contrasting colors and countershading, such as painting the tops and undersides of main gun barrels in dark and light colors, respectively. These schemes were intended to produce the same results as the later dazzle patterns.

This earlier concept had originated with John Graham Kerr, a British biologist, who took his inspiration from natural camouflage in the animal kingdom. American naturalist and artist Abbott Handerson Thayer also promoted the idea of animal-inspired camouflage both in the United States, where he was rebuffed, and to Churchill. After Churchill left the role of First Lord of the Admiralty in 1915, the Royal Navy abandoned these patterns. Kerr unsuccessfully tried to win legally-binding credit for coming up with the idea for disruptive naval camouflage first after World War I ended.

How effective the dazzle patterns actually were in combat remains a topic of debate. Data collected at the time indicated that the camouflage did make it slightly more difficult for enemy submarines to launch attacks, but also made the ships more visible, increasing the total number of attempted attacks.

The Royal Navy continued to use of dazzle patterns, as well as more schemes with more fluid edges known formally as Admiralty Disruptive Pattern, during World War II. Flower class corvettes, such as the original Regina and Moncton, wore both types of paint jobs during the war, among others. The U.S. Navy and the German Navy also employed disruptive schemes.

After World War II ended, dazzle and similar paint schemes quickly fell into disuse. Improved optics and radars increasingly rendered the patterns obsolete. The camouflage that Regina and Moncton are presently wearing, which is based on a World War II design known as the Western Approaches Color Scheme, would offer no defense against warships equipped with modern radars, as well as, long-range infrared surveillance and targeting systems.

Still, the dazzle paint schemes are an interesting reminder of what naval combat looked like during the first half of the last century and a great way to commemorate the achievements and sacrifices the Royal Canadian Navy made to safeguard the trans-Atlantic convoys that played an essential role in supplies Allied forces in crushing the Axis war machine in Europe.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com