To this day, details about the weapons in America’s nuclear arsenal, especially regarding their warheads, remain some of the most secretive, while still publically known, elements America’s nuclear weapons enterprise. There is no better single example of this than a material that the U.S. Department of Energy has used to build thermonuclear warheads, also known as hydrogen bombs, that is so secret that no one knows exactly what it does or exactly what it’s made of, and that is only ever referred to publicly by a codename, Fogbank.

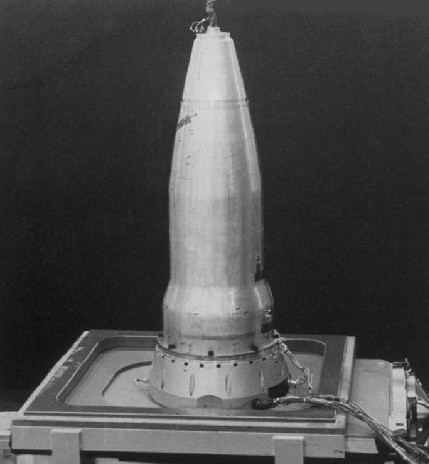

Fogbank first gained relatively widespread public attention between 2007 and 2008 as it emerged that the material was at the root of technical delays in the life extension program for the W76 warhead. The W76 series is employed on Trident II submarine-launched ballistic missiles, also known as Trident D5s, in service with both the U.S. Navy and U.K. Royal Navy. The National Nuclear Security Administration delivered the last life-extended W76-1 warheads in 2018.

“There is a material that we currently use and it’s in a facility that we built … at Y-12,” then-NNSA director Thomas D’Agostino told members of the House of Representatives in 2007, referring to the Y-12 National Security Complex, a nuclear weapons production facility located near the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee. “It’s a very complicated material that – call it the Fogbank. That’s not classified, but it’s a material that’s very important to, you know, our [W76] life extension activity.”

“There’s another material in the [W76] – it’s called interstage material, also known as Fogbank, but the chemical details, of course, are classified,” then-NNSA director Tom D’Agostino told senators later that year.

D’Agostino’s description of Fogbank as an “interstage material” has led experts to largely conclude that it sits between the primary and secondary stages of a two-stage thermonuclear weapon. When the first stage, which is a normal fission reaction, goes off, the interstage material would turn into superheated plasma and then trigger a fusion reaction in the second stage.

Experts also believe that Fogbank is an aerogel, a category of ultralight gels in which the traditionally liquid component is instead a gas. Jeffrey Lewis, an expert on missiles and nuclear weapons at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, posted in 2008 that the codename Fogbank might be derived from nicknames for aerogels, such as “frozen smoke” and “San Franciso fog.” In that same post on the Arms Control Wonk blog, he laid out a number of other known and highly likely details about the material and its production.

Lewis noted that, in 2007, NNSA’s D’Agostino had also told legislators that Fogbank’s production included purifying the material in a process that “uses a cleaning agent that is extremely flammable.” In a talk that same year at the Woodrow Wilson Center, the NNSA director had also “another material that requires a special solvent to be cleaned” and identified the solvent as “ACN,” the abbreviation for acetonitrile, which is commonly used in aerogel production.

“That solvent is very volatile,” D’Agostino said at the time. “It’s very dangerous. It’s explosive.”

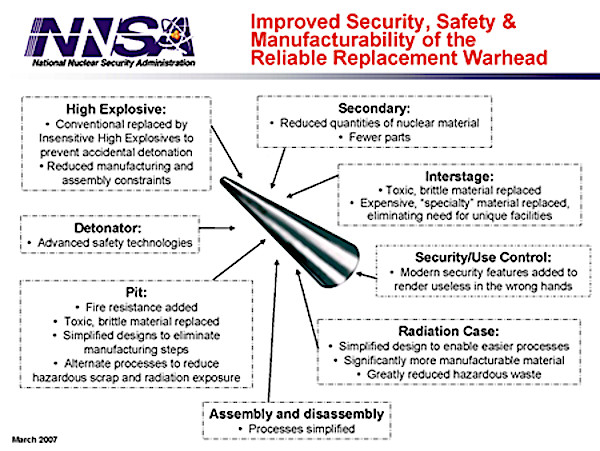

A 2007 NNSA briefing slide on a program known as the Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW), which sought to develop a new warhead design to replace various existing types, further points to Fogbank’s potential aerogel composition. Congress de-funded the RRW effort in 2008 and President Barack Obama formally canceled it the following year.

The NNSA slide specifically noted a desire to replace an “expensive ‘specialty’ material” in the interstage section. This would also have resulted in “eliminating [the] need for unique facilities.”

Y-12 had closed down a top-secret and specialized site known as Facility 9404-11, which was used to produce Fogbank, following the completion of the final W76 warhead in 1989. The complex established what it called a “Purification Facility” in its place.

“It [the Purification Facility] reprocesses a material that we’re taking out of weapons so that we can reuse it in refurbished weapons. That’s probably all I can say,” Dennis Ruddy, who served for a time as President and General Manager of BWXT Y-12, the division of the Babcock & Wilcox Company that operated Y-12 under contract to the U.S. government between 2000 and 2014, once said. “The material is classified. Its composition is classified. Its use in the weapon is classified, and the process itself is classified.”

The Middlebury Institute’s Jeffery Lewis noted in 2008 that it was public knowledge that the Purification Facility at Y-12 worked with ACN. “On three separate occasions in March 2006, workers evacuated the Purification Facility after alarms went off. According to DOE [Department of Energy] documents, the Purification Facility is alarmed to monitor for acetonitrile (ACN) levels,” he explained.

There was also an ACN spill the forced the evacuation of the Purification Facility in December 2014, which thankfully caused no injuries. It took months to get the facility back up and running. An alert about another potential accident in March 2015 turned out to be a false alarm.

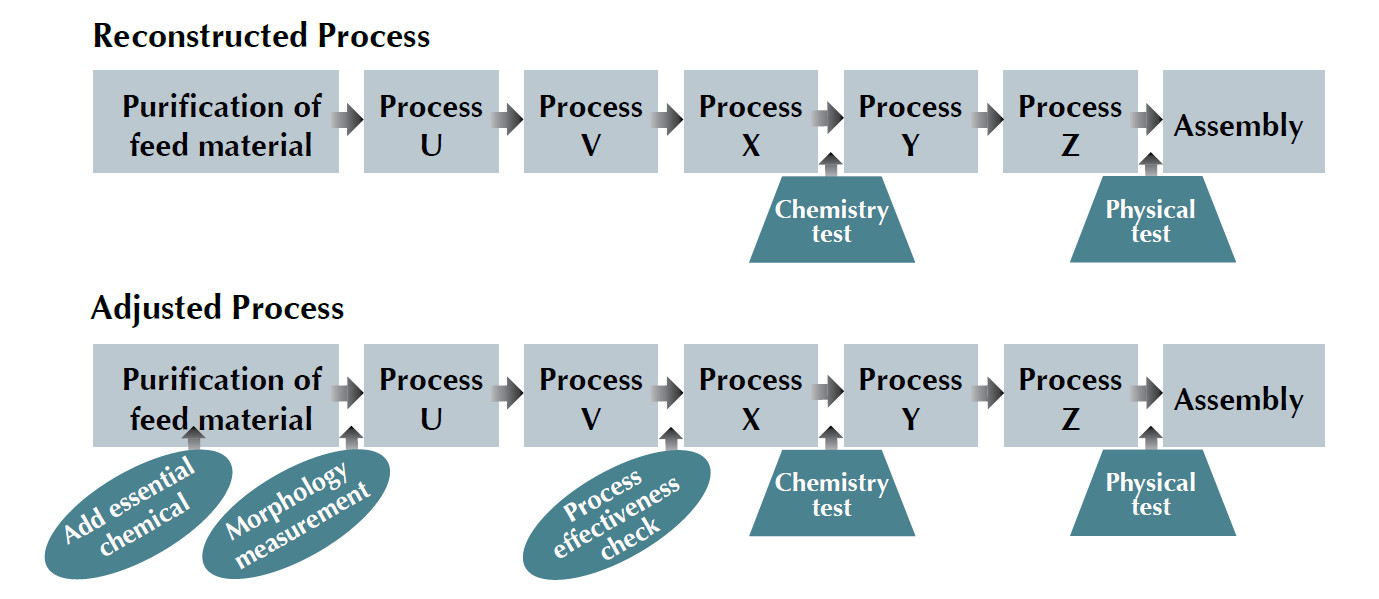

In 2009, an article had also appeared in an issue of Nuclear Weapons Journal, an official publication of the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL), which disclosed that the decision to re-start manufacturing Fogbank came in 2000 and confirmed that this decision was linked directly to the W76-1 warhead project. It also explained that in the intervening years, NNSA had lost virtually all of its institutional knowledge base regarding Fogbank and how to make it.

“Most personnel involved with the original production process were no longer available,” the article said. As such, NNSA personnel had reconstructed the production process from historical records.

In addition, “a new facility had to be constructed, one that met modern health and safety requirements.” That facility is very likely the Purification Facility at Y-12.

In a bizarre twist, the new production facility and reverse-engineered production process yielded a version of Fogbank that was of a higher purity than it had been in the past, according to the article. The problem, however, was that for Fogbank to work as intended in existing warhead designs, that previous level of impurity was actually essential. NNSA had to revise the process to ensure the final product was just as impure.

NNSA only succeeded in recertifying the production process in 2008, the better part of a decade after first deciding to restart Fogbank production. The production of life-extended W76-1 warheads began that same year.

It’s not clear how many U.S. nuclear warhead types, past and present, used Fogbank. Jeffery Lewis’ has posited that the W78 and W80, used on the U.S. Air Force’s LGM-30G Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missile and the AGM-86B Air-Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM), respectively, might have it based on when NNSA designed and produced those warheads.

Fogbank, or at the least the story of re-booting its production, has come up more recently amid the broad U.S. efforts to modernize America’s nuclear arsenal in recent years. This has included the fielding of a controversial low-yield variant of the W76, which entered service on some U.S. Navy’s Trident II submarine-launched ballistic missiles earlier this year, and the development of a new warhead, the W93, for those same missiles.

Work on the W93, in particular, has raised concerns about whether the Department of Energy, which oversees warhead construction, has adequate facilities and other resources to avoid potentially serious delays in the production of large numbers of new nuclear weapons. In March 2020, Allison B. Bawden, a Director on the Natural Resources and Environment team at the Government Accountability Office highlighted the past difficulties with the production of Fogbank in relation to the production of new nuclear weapons.

“Future weapon programs will require newly produced explosives, including some that NNSA has not produced at scale since 1993,” Bawden said during a hearing on Capitol Hill. “As we reported in March 2009, NNSA had to delay first production of the W76-1 from September 2007 to September 2008 when it encountered problems restarting production of a key material, known as Fogbank. NNSA is working to reconstitute its high explosives capabilities, as we reported in June 2019.”

You can read more about the production of specialized high explosives for nuclear weapons in this past War Zone piece.

The exact origins of the W93 design are unclear. Senior Department of Energy and U.S. military officials have shied away from calling it all-new, but it is certainly set to the be the first new warhead design to enter U.S. military service since the introduction of the W88 for the Trident II in 1989.

The W93 is based on “previously nuclear-tested designs, it’s not going to require any nuclear testing,” a senior defense official had told reporters in February. However, U.S. Navy Admiral Charles Richard, head of U.S. Strategic Command, told legislators that same month that the W93 itself “hasn’t been designed yet.”

The Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW) program had raised similar questions. NNSA had picked Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) to build the initial production version of the RRW, leading to speculation that it might be derived from LLNL’s W89. Work on the W89, which was intended to arm the Air Force’s air-launched AGM-131A Short Range Attack Missile II (SRAM II) and the Navy’s RUM/UUM-125A Sea Lance anti-submarine missile, officially ended in 1991. Neither the SRAM II nor the Sea Lance entered service, either.

It is possible that the W93 project will now leverage work from the RRW program, regardless of the latter’s origins. If the W93 does follow on from that earlier effort, there is also a distinct possibility that it will not use Fogbank in its interstage section.

Whatever happens, Fogbank will continue to be a prime example of both the complexity surrounding the construction of nuclear warheads, as well as the immense secrecy surrounding America’s nuclear weapon enterprise.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com