The U.S. Navy’s two massive hospital ships, the USNS Comfort and USNS Mercy, are presently deployed to Los Angeles, California and New York City, New York, respectively. Both vessels are helping to ease the burden on hospitals ashore that are treating growing numbers of patients with the COVID-19 novel coronavirus by providing critical medical attention to individuals with other, unrelated ailments. The ships have become an important symbol of the U.S. government’s response to the pandemic, which makes it all the more interesting to remember that the Navy pushed to retire them two years ago.

Mercy began treating patients on Mar, 30, 2020, three days after arriving in the Port of Los Angeles. Comfort also arrived in New York Harbor on Mar. 30. The Navy had rushed to activate the ships earlier in March – Comfort

was actually undergoing maintenance when the service first ordered the deployments – as COVID-19 cases continued to grow exponentially, especially in New York City, which has become a major epicenter for the pandemic in the United States.

“The USNS Comfort arrives in New York City this morning with more than 1,100 medical personnel who are ready to provide safe, high-quality health care to non-COVID patients,” U.S. Navy Captain Patrick Amersbach, who is the top officer in charge of the hospital ship’s onboard medical facilities, said in a statement on Mar. 30. “Like her sister ship, USNS Mercy, which recently moored in Los Angeles, this great ship will support civil authorities by increasing medical capacity and collaboration for medical assistance.”

The Navy first acquired the two hospital ships, which are both converted oil tankers, in 1986 and 1987. Each one is approximately 900 feet long and displaces around 69,360 tons with a full load. The U.S. Naval Institute noted that if you stood Comfort on her stern on the pier in New York Harbor, she’d be the thirteenth tallest building in the city.

The ships have a typical crew complement of around 1,200 personnel, consisting of both uniformed members of the military and civilian mariners. Comfort presently has a crew of more than 1,200, drawn from 22 different naval commands, according to the Navy. The service does not appear to have released a similar breakdown of the personnel on board Mercy.

The ships were designed primarily to handle combat casualties during expeditionary operations overseas and can accommodate up to 1,000 patients at a time, including 80 in an intensive care unit. Comfort and Mercy both have an array of other specialized medical facilities more commonly found in hospitals ashore, including a dozen operating suites, burn wards, a testing laboratory, MRI and x-ray equipment, a blood bank, and the ability to generate its own oxygen. You can read more about these ships in this past War Zone piece.

Both of the hospital ships have demonstrated their ability to respond to humanitarian crises and natural disasters, and perform other less intensive non-combat missions, in the United States and abroad. Comfort notably also sailed to New York City to help in the aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

The Navy, as well as the Pentagon, has stressed that the hospital ships, with their wide-open treatment bays, are not properly configured to adequately treat patients with readily transmissible COVID-19 coronavirus. However, they have offered a valuable way to expand general medical capacity relatively quickly so facilities ashore can focus on patients who have contracted the virus.

However, had the Navy gotten its way two years ago, one or both of these ships would not have been available now. In its budget proposal for the 2019 Fiscal Year, which the service released in the Spring of 2018, it proposed sending either Comfort or Mercy, or both, into mothballs. The Navy cited the high costs involved in operating and maintaining the pair of unique ships, as well as their age and new distributed concepts of operations, in announcing its decision.

“The problem with those [hospital] ships is, there’s only two of them, and they’re big, and we’re moving to a more distributed maritime operations construct,” U.S. Navy Vice Admiral William Merz, then Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Warfare Systems, told members of Congress in April 2018. “There’s no lack of commitment [to this medical capability]; matter of fact, we’re taking a broader look at the capabilities on whether or not they are aligned with the way we plan to fight our future battles.”

This was hardly the first time the Navy had tried to retire Comfort and Mercy. “They’re wonderful ships, but they’re dinosaurs,” now-retired U.S. Navy Vice Admiral Michael Cowan, then the Surgeon General of the United States Navy, said in 2004. “They were designed in the ’70s, built in the ’80s, and frankly, they’re obsolete.”

Members of Congress quickly pushed back against the Navy’s proposal in 2018, arguing both that the ships continued to provide valuable capabilities for military operations in the absence of a direct replacement. Lawmakers also argued that the vessels offered invaluable utility for humanitarian missions and a useful way to project so-called “soft power” to help advance American interests overseas.

“We have an obligation to our soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines, and also the civilians across this world… Because there will come a time when we need that [hospital ship capability] and we need to always be ready,” Representative Trent Kelly, a Mississippi Republican said in defense of the ships during a hearing in March 2018. He also highlighted Comfort‘s deployment to both his state and Louisiana in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

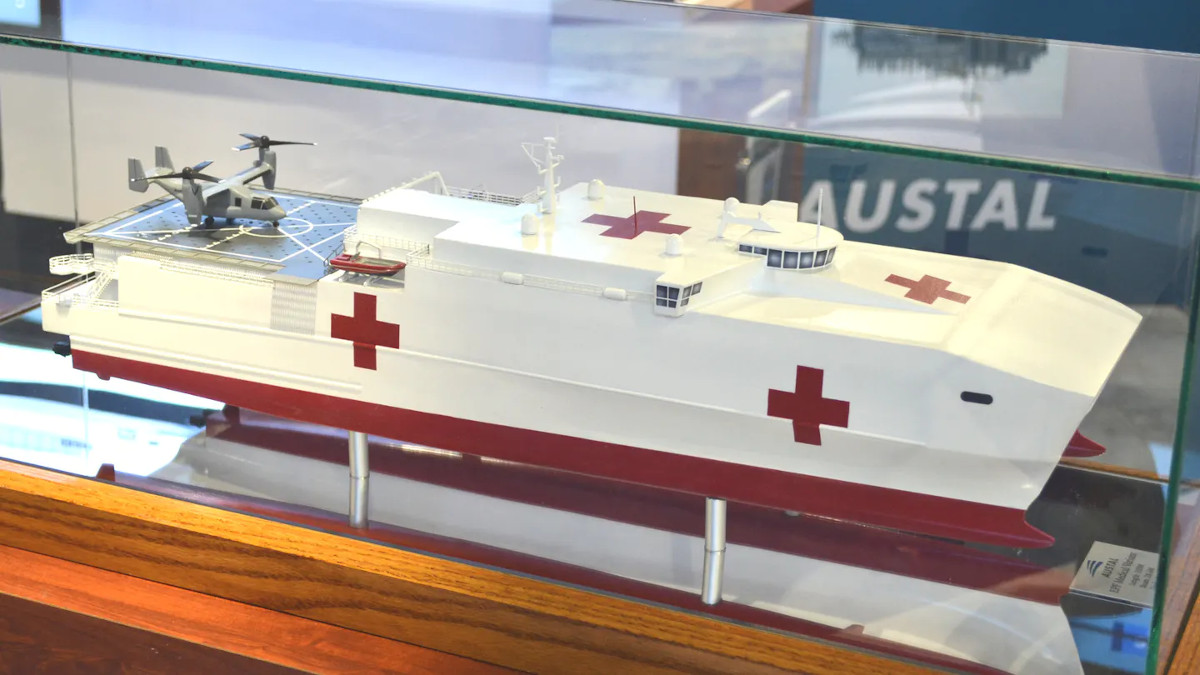

The Navy ultimately dropped its plans to retire the hospital ships without a direct replacement. Since then the service has been exploring a number of future options, including containerized medical facilities that it could deploy onboard various existing ships, including its Expeditionary Sea Base (ESB) ships and its much smaller Spearhead class expeditionary fast transports.

The Common Hull Auxiliary Multi-Mission Platform (CHAMP) program, which sought to develop a fleet of auxiliary ships for various missions at a lower cost by using a common hullform, was also supposed to include a hospital ship variant. In December 2019, the White House’s Office of Budget and Management sent a memorandum to the Navy that, among other things, ordered it to effectively cancel its existing CHAMP plans and develop a lower-cost proposal. The Navy had expected to begin buying the first CHAMP ships in 2025, but those plans are now uncertain.

It has certainly turned out to be a good decision not to retire the Comfort and the Mercy without any replacements in service. Representative Kelly’s comments about how there would come a time when we absolutely needed the ships to be ready has definitely come true.

“We are ready and grateful to serve the needs of our nation,” the Comfort’s Captain Amersbach said yesterday. The nation is equally grateful, and lucky, that the hospital ships, among other military capabilities, are available to help combat the spread of COVID-19.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com