Nearly a decade ago, the U.S. Intelligence Community began work on an experimental ultra-quiet, high-efficiency reconnaissance drone with an advanced hybrid-electric propulsion system. Very limited details about this secretive project, known as Great Horned Owl, have emerged since then. Now, The War Zone can share previously unseen schematics and other details about the resulting stealthy flying-wing-shaped unmanned aircraft called the XRQ-72A, which Scaled Composites, a subsidiary of Northrop Grumman well known for producing advanced aircraft designs, developed.

The

War Zone obtained the information via a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to the U.S. Air Force. The Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) supported the Great Horned Owl program, which the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) first disclosed in 2011. IARPA is one of the Intelligence Community’s top research and development arms and answers to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. It’s not clear which intelligence agency or agencies may have had requirements that led to the Great Horned Owl effort, but the CIA has operated a variety of drones with a wide range of capabilities over the years to conduct various missions.

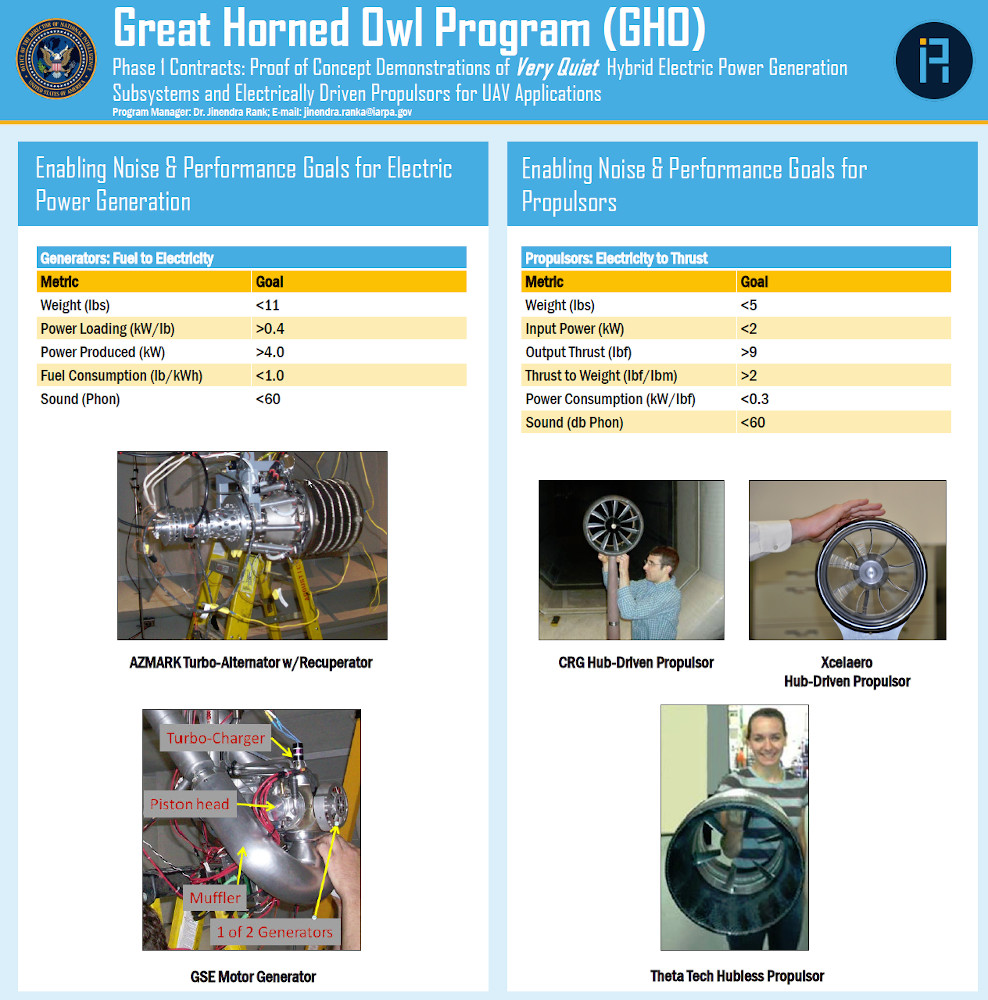

“The Intelligence Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR) role for UAVs [unmanned aerial vehicles] is dependent upon the ability of the UAV to do its mission without the adversary being able to counter it. For many such ISR applications, the acoustic signature of the UAV alerts the adversary to the UAV’s presence and can interfere with the mission,” IARPA explained in a public notice regarding the Great Horned Owl effort in 2011. “Battery powered UAVs are very quiet but lack endurance and payload capability. Better, more efficient, quiet power sources and propulsion techniques are needed to build next generation UAVs for ISR mission applications.”

The resulting XRQ-72A has a general planform reminiscent of other Northrop Grumman designs, including that of the B-21 Raider stealth bomber. It also has some broad external visual similarities to flying wing unmanned aircraft that other companies have developed over the years, including designs from Lockheed Martin.

The drone has a 30-foot wingspan, is 11.2-feet long measured from the nose to the ends of the wingtips, and is four feet tall when including the vertical wingtip stabilizers, according to the schematics we obtained via FOIA. Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works’ X-44A, which The War Zone was first to report on and which the Air Force did not publicly acknowledge until 2018, also has a wingspan of around 30 feet. The X-44A represented an important “missing link” in the chronology of that company’s advanced flying wing drone developments, including the RQ-170 Sentinel stealth drone.

It’s not clear how heavy the XRQ-72A is, but another AFRL document we received said that the Great Horned Owl program’s requirements called for an air vehicle weighing between 300 to 400 pounds. The drone also appears to have at least some stealthy features, including its general shape and shrouded exhausts, and is made out of composite materials.

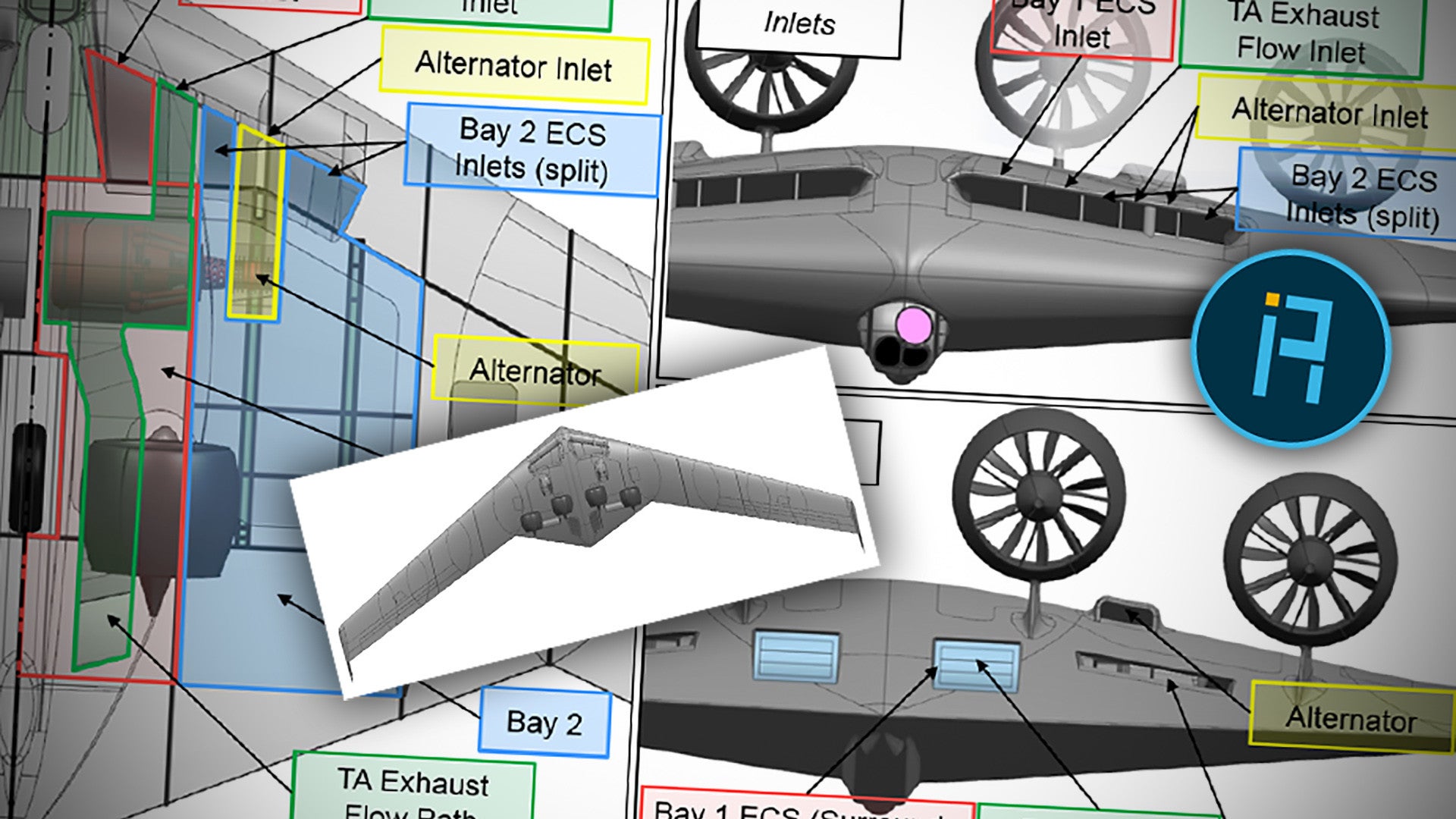

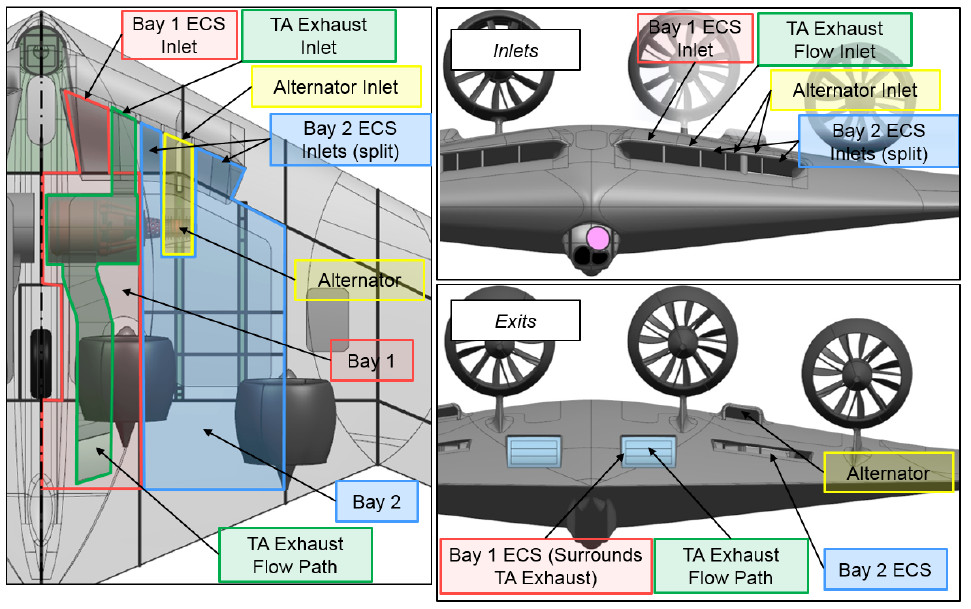

Its most important feature, of course, is its hybrid propulsion system. A pair of fuel-powered generators inside the central fuselage produce the electricity that powers four ducted fan propulsors mounted on top of the aircraft’s flying-wing fuselage. This is in some ways visually reminiscent of the general configuration of the Boeing X-48 series of experimental unmanned blended wing body demonstrators, but those aircraft used small turbojet engines.

The schematics also show the XRQ-72A equipped with a typical ball-type sensor turret, which could include various types of video cameras. IARPA made no specific mention of what sensors it might be interested in any Great Horned Owl demonstrator being able to carry in its original 2011 announcement.

It’s not clear from the Air Force documents how the drone takes off or lands. There no landing gear present in the schematics, which could point to runway-independent operation using a catapult or rocket-assisted zero-length launch system.

The Great Horned Owl program was initially focused simply on exploring technologies that could enable the development of a very quiet and efficient unmanned intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance drone. Hybrid propulsion concepts, which have been and continue to be of great interest to both military and commercial aviation communities, offer a potential path to significant improvements in fuel efficiency, reliability, and reduced acoustic signature over traditional aircraft propulsion concepts. AFRL is still experimenting with these ideas today, which you can read about in much greater detail in this past War Zone piece.

The XRQ-72A’s exact capabilities are unclear. AFRL said that it expected the drone to have a “low acoustic signature at a speed of 50 KEAS [Knots Equivalent Air Speed],” according to the documents we obtained via FOIA. IARPA’s stated goals in 2011 were a high-efficiency design that could be as quiet as 50 Phons at speeds up to 100 knots. A Phon is a unit of sound measurement equivalent to 1 decibel at a frequency of 1 kilohertz.

Sound can be hard to measure. A typical conversation, where people are speaking without raised voices, or the hum of a dishwasher are typically described as being around 50 decibels loud, though that dissipates the further away you get from the source. A typical jet engine on a commercial airliner still registers around 130 decibels or more during takeoff, even at a distance of 100 feet.

In 2012, IARPA did issue contracts to various companies to craft various ducted fan designs, as well as other propulsion system components as part of Phase 1 of the Great Horned Owl program. CRG and Xcelaero supplied hub-driven propulsors, while a firm called Theta Tech developed a hubless, or rim-driven design. As their name implies, hub-driven propulsors have a centrally mounted propeller inside the propulsor. A hubless design has fan blades mounted on the inside of a ring that rotates within the body of the propulsor. The schematic of the Northrop Grumman XRQ-72A shows hub-driven propulsors.

The exact timeline of the Great Horned Owl program, including whether or not it is still ongoing, is not entirely clear, either. When IARPA first announced the project publicly in 2011, it said it expected it to wrap up in June 2016. This schedule included plans for a second phase involving system integration and ground testing and a third phase with actual flight testing.

At least one testbed drone emerged during that timeframe, called Talos. Oklahoma State University’s Unmanned Aircraft Systems program helped develop this unmanned aircraft, which first flew in 2013. Talos is a completely different design from Northrop Grumman’s XRQ-72A with a more traditional wing configuration and overall planform.

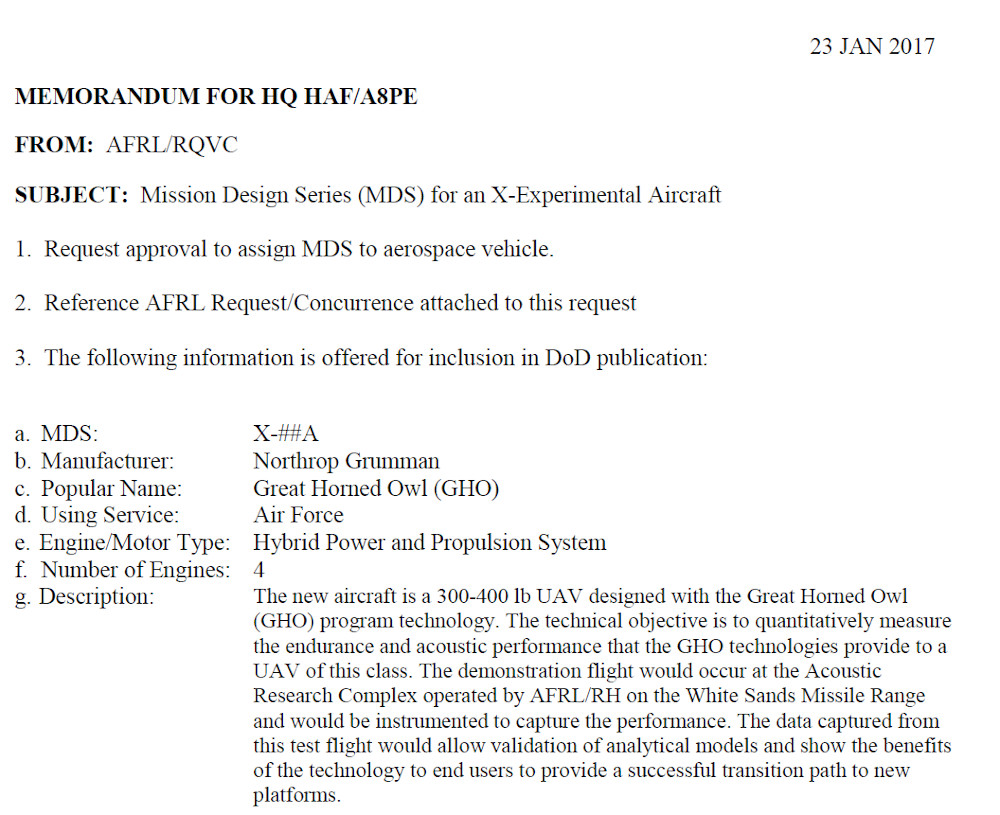

However, AFRL only requested a formal designation for the Great Horned Owl drone in January 2017, according to the documents we received via the FOIA request. “It is planned that the GHO [Great Horned Owl] demonstrator would complete a series of flights at the Acoustic Research Complex operated by AFRL/RH [Airman Systems Directorate] on the White Sands Missile Range incorporating the hybrid power and propulsion system, and then be available for future demonstrations of additional technology and/or vehicle configurations,” the memorandum explained.

What’s also interesting is that AFRL asked for an X-plane designation, which are typically applied only to purely experimental aircraft. One notable exception was the Bell X-16, which was publicly described as a high-altitude testbed, but was, in fact, a competitor to the famous U-2 Dragon Lady spy plane.

“The X-## Mission Design Series Assignment is very important at this time to highlight to the aerospace R&D community the importance of the development of hybrid power and propulsion for future USAF aircraft,” the memo noted. “While potential benefits to a broad range of future vehicles have been identified, such a dramatic change in the design paradigm is a slow process. The X-## designation for the GHO will dramatically improve awareness of the research and help preserve the technical achievements, increasing opportunity for technical transition of the experimental results and design philosophy to future USAF air vehicles.”

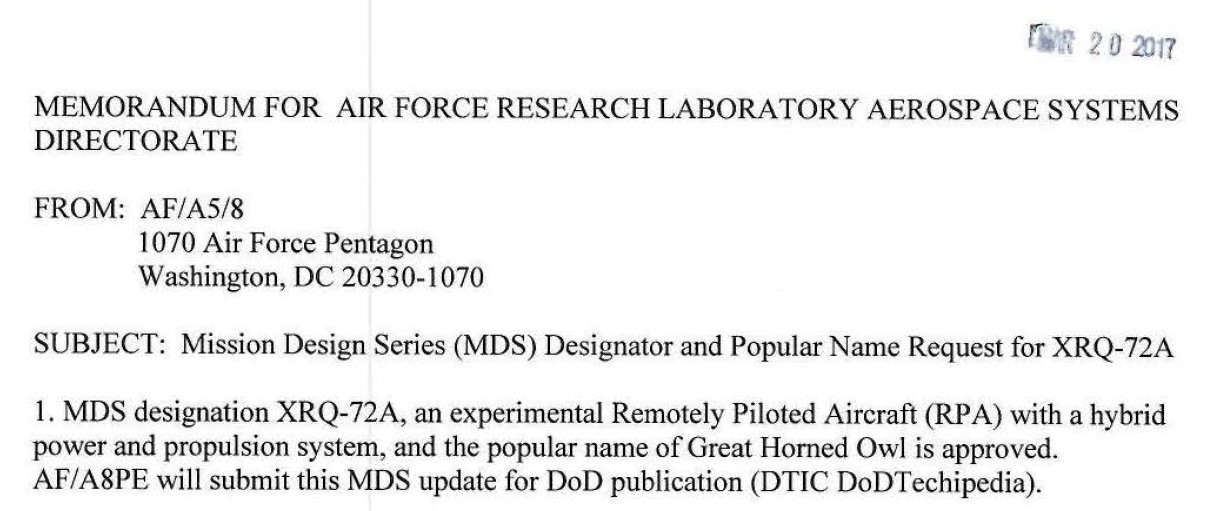

It’s not clear how the final XRQ-72A designation, which the Air Force approved in March 2017, came about. The “XRQ” prefix is very much not an X-plane designation and is more fitting for a prototype of a potentially operational platform. There numerous examples of experimental drones with “XQ” or just “X” prefixes, such as the Kratos XQ-58A Valkyrie and the Lockheed Martin X-44A, as well as the still curious YQ-11 prototype designation for the General Atomics Predator C/Avenger, so this appears to have been a deliberate decision.

The number 72 is also wildly out of sequence for either the X-plane category or the drone category in the U.S. military’s joint-service aircraft designation system. It is a number that has been informally applied on multiple occasions to advanced intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance aircraft designs in the past, as a reference to being a spiritual successor to the iconic SR-71 Blackbird spy plane.

In 2018, IARPA also initiated a follow-on project called Little Horned Owl, which had similar goals to Great Horned Owl, but called for a notably smaller overall design that would only have to carry a 10-pound payload. There was also a requirement for “innovative battery architecture to improve flight times for battery-only flight” and “runway independent operation (minimal ground support equipment).”

Regardless, as IARPA noted in 2011, there is a clear demand for the kind of technologies developed under the Great Horned Owl program. A drone with relatively long endurance and very quiet operation would enable persistent surveillance of targets of interest with a reduced likelihood of detection.

This, of course, would hardly be the first time the U.S. Intelligence Community, or the U.S. military, has acquired or otherwise experimented with ultra-quiet aircraft for reconnaissance and covert operations. The CIA famously used a pair of Hughes 500P helicopters, also known as the “Quiet Ones,” to conduct a top-secret wire-tapping operation in North Vietnam during the Vietnam War. The U.S. Navy and the U.S. Army also experimented with very-quiet manned surveillance aircraft, such as the YO-3A Quiet Star, during the Vietnam War.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the Army, as well as the U.S. Air Force and the CIA, further pursued higher-flying manned surveillance aircraft with low acoustic signatures, most notably the RG-8A Condor powered glider, some of which later found their way into U.S. Coast Guard service. The Coast Guard went on to fly the unique RU-38A Twin Condor, as well. You can read more about these aircraft, and the Coast Guard’s attempts to develop a successor, in this past War Zone piece.

When it comes to more modern quiet drones, The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has been pursuing similar developments for U.S. military use. In 2006, Lockheed Martin also supplied a hand-launched, electrically-powered drone called Stalker to an unnamed customer, reportedly U.S. Special Operations Command, specifically to meet a requirement for a quieter unmanned aircraft that opponents would have a harder time detecting. More recently, the company developed a propeller-driven flying wing design, called Fury, which is visually similar to the RQ-170, albeit smaller, and that also has a reduced acoustic signature.

The XRQ-72A represents a more advanced concept than smaller designs, such as the Stalker or the Fury, though. The Great Horned Owl program, as well as Little Horned Owl, also underscores how the U.S. Intelligence Community is driving unmanned aircraft developments themselves, including in the classified realm, independent of the U.S. military, though there is clear cooperation between them. The Department of Homeland Security had also expressed an interest in the outcome of the Great Horned Owl program to support the development of future unmanned aircraft for border surveillance.

Much about the XRQ-72A still remains a mystery and The War Zone has already begun working to uncover more about this drone and the shadowy program that spawned it. The biggest question is whether the drone, or further improved design based on the work done under Great Horned Owl program, is silently roaming the skies today.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com