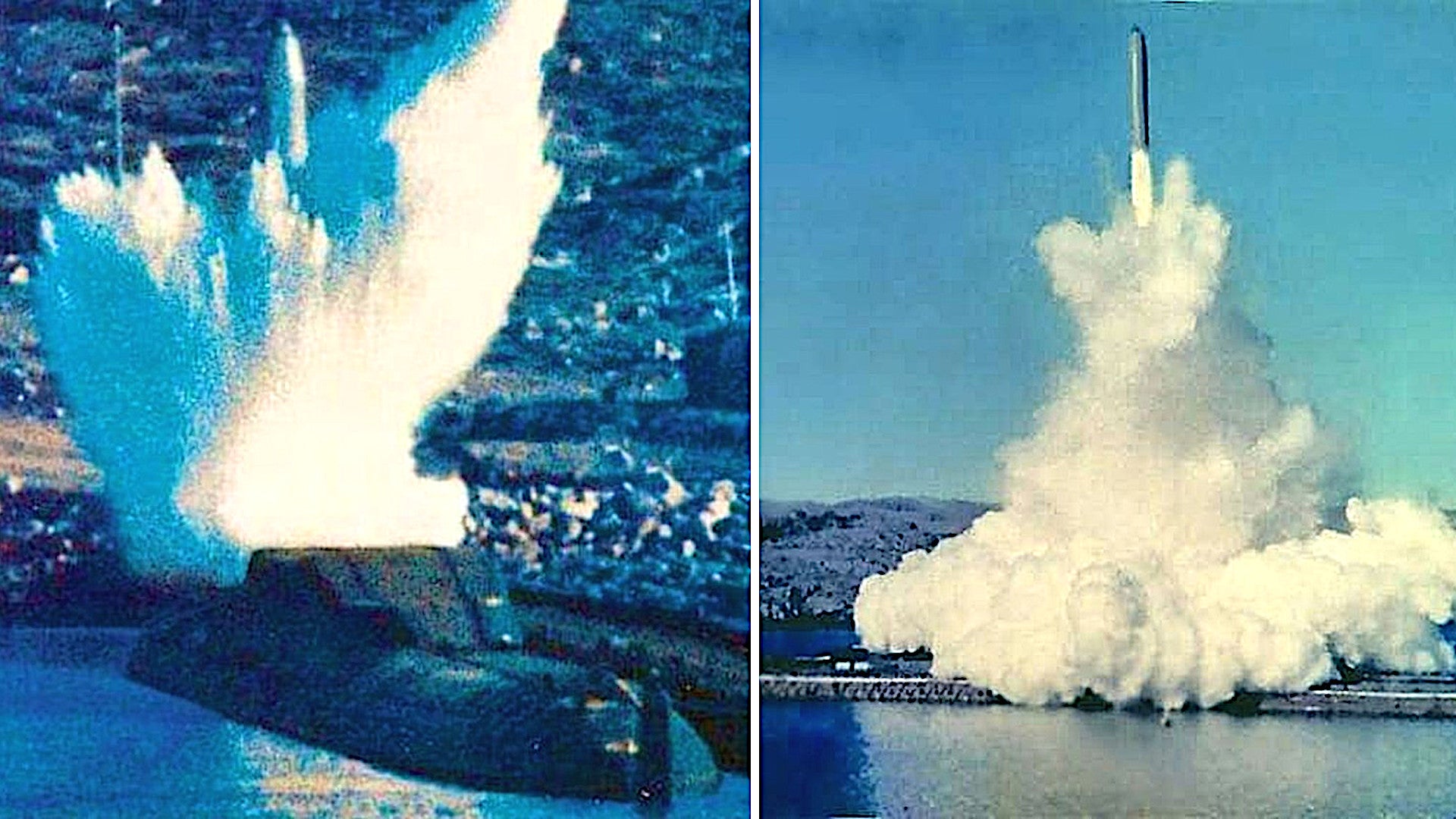

Pictures have been circulating online of a Soviet Delta III class nuclear ballistic missile submarine firing an R-29R submarine-launched ballistic missile during an exercise while still in port, a unique tactic that no other country appears to have ever employed. Last year, the Russian Navy reportedly conducted a similar test, but which involved a Yasen class guided-missile submarine conducting a pier-side launch of a Kalibr cruise missile, apparently for the first time ever.

The date and exact circumstances of the particular exercise seen in the photos on social media are unclear. An article in Russia’s Izvestia newspaper in 2019 said that the Soviet Navy had first begun training ballistic missile submarine crews to carry out these pier-side launches in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

This would fit broadly with the fact that a Delta III class submarine is seen in the pictures firing the R-29R missile. The Soviet Navy commissioned the first of the Delta IIIs, also known as Project 667BDR Kalmar class boats, in 1976.

The last member of the 14-ship class entered Soviet Navy service in 1982. The posts online generally agree that the launch took place prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Today, just one of these submarines, the Razan, also known as K-44, remains in active service as a ballistic missile submarine. Another Delta III, the Orenburg, or BS-136, is also still sailing, but has been converted into a special projects submarine capable of serving as a mother ship for small spy submarines, which you can read more about in this past War Zone piece.

Nuclear ballistic missile submarines, or boomers, such as the Delta IIIs, have long offered the countries that operate them invaluable nuclear second-strike deterrent capabilities. This is in no small part because of their ability to operate submerged, often cruising slowly and quietly in remote areas, for weeks or months at a time.

Why the Russians decided to train their boomer crews to also be prepared to have them launch their world-ending weapons without ever leaving port is not entirely clear. “The fleet does not always have the deployment time necessary for the ships to depart from the pier and proceed to the previously designated strike area,” Igor Kurdin, a retired Russian Navy submarine captain and head of the St. Petersburg Club of Submariners, a naval veterans organization, told Izvestia last year.

The R-29R has a range of just under 4,040 miles, which would have allowed submarines armed with those missiles, such as the Delta IIIs, to hit anywhere in Europe, as well as portions of Alaska, Canada, and the northeastern United States, from naval bases in Russia’s northwestern corner. Ballistic missile submarines based in Russia’s Far East region would have been within range of Alaska, as well as, along with Hawaii and other targets in the Western Pacific, such as major American military bases on Guam.

While the submarines would not be hidden in any way while in port, being able to fire their missiles while still moored at the pier would have made them a standing threat at all times. The Soviets could also have made use of the submarines without the need to find a full crew and otherwise provision them for long cruises, if necessary.

The tactic would also have given the Soviets some added defense against a first strike or otherwise losing ballistic missile submarines in port before they could fire their missiles during the initial wave of strikes in a nuclear conflict. Submarine bases would have been high priority targets in either of those scenarios and, as the retired Russian Navy captain Kurdin noted, the boomers might not have been able to escape out to sea before incoming strikes hit. Being able to fire their missiles from their moorings would have allowed them to still attempt to launch retaliatory strikes before being destroyed.

There are, of course, risks and drawbacks to doing this, as well, not least of which what could happen if the missile were to fail for some reason. The shock and blast from firing the missiles might also cause increased wear and tear, and even damage, to the submarine’s moorings.

There is no indication that the U.S. Navy, or any other country that operates nuclear ballistic missile submarines, has ever experimented with or actively trained to employ this same tactic. It’s unclear whether the Russian Navy continued to train boomer crews to carry out these operations after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In March 2019, Izvestia did report that Russia’s sole Project 885 Yasen class guided-missile submarine, the Severodvinsk, had fired a Kalibr land-attack cruise missile while pier-side at the Nerpichya Naval Base, part of the larger Zapadnaya Litsa base, in Murmansk. This appeared to indicate a more recent revival of the tactic that was afforded by the fact that the Severodvinsk has a vertical launch capability. Other Russian submarines capable of firing Kalibrs do so by launching them via their torpedo tubes, something that cannot be readily done in port.

The 3M-14 variants of Kalibr, which can carry nuclear warheads, have a range between 930 and 1,500 miles, according to publicly available information. Russia is also reportedly working on a new, extended-range Kalibr-M that can hit targets over 2,800 miles away, at least.

With a range of 1,500 miles, Severodvinsk, or any other submarine capable of vertically launching these variants of Kalibr, such as the improved Project 885M Yasen-M submarines now under construction, could strike targets across Scandanavia and in northern Europe, as well as Iceland, on short notice from bases in northeastern

Russia. Other improved cruise missiles, such as the shadowy hypersonic 3M22 Zircon, which is in development now, could further expand those capabilities. From what we know, however, Zircon has a significantly shorter range than Kalibr.

Increased Russian submarine activity in the Atlantic has become a particular point of concern for the U.S. military, as well as its NATO allies, in recent years, which you can read about more in these past War Zone stories. The Kalibr cruise missile has also come up as representing an especially notable threat to America’s European allies and partners.

“The Kalibr class cruise missile, for example, has been launched from coastal-defense systems, long-range aircraft, and submarines off the coast of Syria,” U.S. Navy Admiral James Foggo, head of U.S. Naval Forces Europe and commander of NATO’s Allied Joint Force Command Naples, said in 2018. “They’ve shown the capability to be able to reach pretty much all the capitals in Europe from any of the bodies of water that surround Europe.”

Russia’s revival of the tactic of being able to fire missiles from submarines in port only increases the flexibility of Severodvinsk and other future guided-missile submarines with vertical launch system capabilities, even in times where there might be too few resources to actually put them out to sea. It offers the benefit of being able to make use of boats on short notice for long-range strikes and reducing the chance of a pre-emptive strike negating their retaliatory capability just as it did for the Soviet Navy’s boomers.

If nothing else, it’s another example of interesting and unique naval tactics and capabilities that the Soviets developed during the Cold War and that continue to inform Russian Navy operations to this day.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com