The U.S. Marine Corps has an ambitious 10-year transformation plan that could see the service eliminate its entire tank force, dramatically scale back howitzer batteries, and cut a significant number of aviation units in favor of land-based rocket artillery and stand-off missile launchers and unmanned aircraft. The proposal follows an already dramatic announcement from the Corps’ top officer last year about the need to move away from reliance on large traditional amphibious warfare ships, something The War Zone explored in depth. All of this is rooted in the prevailing view that Marines will have to fight in small groups and in a distributed fashion in any major conflict in the future, especially in the Pacific region, in order to remain relevant.

The Wall Street Journal was the first to report on the Marines plans for the radical shift on Mar. 23, 2020. The newspaper interviewed Marine

Corps Commandant General David Berger about his proposal, which would fundamentally change the face of his service for years to come.

“China, in terms of military capability, is the pacing threat,” Berger told the Journal. “If we did nothing, we would be passed.”

“I have come to the conclusion that we need to contract the size of the Marine Corps to get quality,” he added.

“The wargames do show that, absent significant change, the Marine Corps will not be in a position to be relevant” in a high-end conflict against a “peer competitor,” U.S. Marine Corps Lieutenant General Eric Smith, head of the Marine Corps Combat Development Command, also explained to the Journal. Berger had been head of this command, which is responsible for developing new and improved concepts of operations for the Corps, before becoming Commandant.

Berger’s contraction is significant and wide-ranging. Over the next decade, he wants to shrink the entire size of the Corps from approximately 189,000 personnel to 170,000.

To do this, he would get rid of a number of units, including all seven existing Marine tank companies, along with their M1 Abrams and support vehicles. Three bridging companies, necessary to get those heavy vehicles across waterways, would go get shuttered. Marine armored vehicles fleets would be limited to the service’s existing fleet of LAV-25 8×8 wheeled armored vehicles and its new Amphibious Combat Vehicles (ACV), another 8×8 wheeled design. The ACV will increasingly supplant the tracked Assault Amphibious Vehicles (AAV) in the coming years.

“We need an Army with lots of tanks,” Berger said. “We don’t need a Marine Corps with tanks.”

The total number of 155mm howitzer batteries would also drop from 21 to just five. Three of the 24 infantry battalions are also set to get cut under the plan, though the Marines have talked about increasing the size of infantry squads, and by extension the remaining infantry units, at the same time.

The total number of Marine fighter attack squadrons, all of which are transitioning to variants of the F-35, would remain at 18. However, the size of each of these squadrons will shrink from 16 aircraft to just 10, according to a separate report from USNI News.

Three MV-22B Osprey tilt-rotor squadrons, two light attack helicopter squadrons equipped with AH-1Z Vipers and UH-1Y Venoms, and three heavy helicopter squadrons are all set to get cut from the overall force structure. The latter of these units are equipped with CH-53E Super Stallion helicopters, which are set to get replaced by CH-53K King Stallions. Trimming those squadrons could impact the total number of CH-53Ks, which have had a long-troubled development, the Marines expect to buy in the end.

Despite this contraction, Berger is planning to make additions, as well, including tripling the size of land-based rocket artillery and stand-off missile units from seven to 21. This would include M142 High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems (HIMARS) launchers that the Marines want to be able to fire Naval Strike Missile anti-ship missiles in the future, in addition to 227mm guided artillery rockets and short-range quasi-ballistic missiles. The Corps is also planning to introduce land-based launchers able to fire the Tomahawk cruise missile.

The Marines’ unmanned aircraft force would also double in size, from three to six squadrons. The service is very much in the process of defining exactly how it envisions the composition of these drone fleets. In its most recent budget request for the 2021 Fiscal Year, submitted as part of the larger U.S. Navy proposal, the Corps’ revealed that it was reassessing its Marine Air Ground Task Force Unmanned Aircraft System Expeditionary program, or MUX, as well as scaling back plans to acquire MQ-9 Reapers in the interim.

The present plan includes exploring a “system of systems” that could including various smaller drones, as well as larger, land-based unmanned aircraft. The original MUX concept, which you can read about in more detail in this past War Zone piece, had envisioned large Marine unmanned aircraft capable of performing various complex roles and intended to operate from large amphibious warships.

The Marines would also add another squadron of KC-130J Hercules aerial refueling tankers, which can also serve as airlifters and gunships.

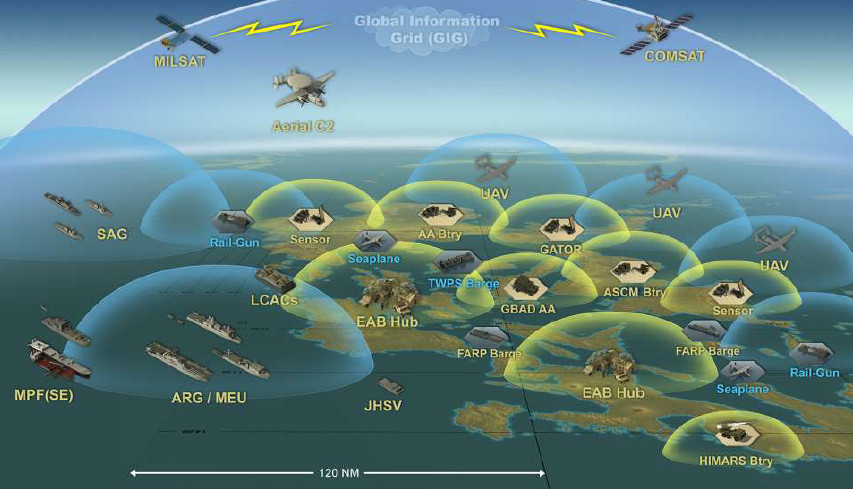

These massive force structure changes are driven in part by budgetary concerns, as well as a new, over-arching operating concept the Marines have been experimenting with, on paper and during exercises, called Expeditionary Advance Base Operations (EABO), for some years now. EABO is heavily center on an idea of an island-hopping blitzkrieg of sorts during a major conflict in the Pacific region where ground units could easily find themselves distributed across a front thousands of miles long separated by large expanses of water.

Unlike the other U.S. military services, even the U.S. Army, the Marines do not expect to have the capacity to conduct large-scale stand-off operations and plan to fight almost exclusively inside “the weapons engagement zone” of a potential opponent, such as China, according to the Journal. China, in particular, has invested significant resources in the development and fielding of anti-access and area denial capabilities, including air, sea, and ground-launched anti-ship cruise missiles, as well as medium and intermediate-range ballistic missiles, including air-launched ones, some of which carry hypersonic boost-glide vehicles or that may have anti-ship capabilities. Longer-range surface-to-air missiles and supporting sensors are also part of the picture. All of this forces large traditional amphibious warfare ships to operate further and further from actual objectives, limiting the ability of the Marine Corps in its present configuration to contribute in the minds of Berger and other senior service officials.

Under the EABO concept, smaller elements of Marines would use air assaults and smaller ships, including unmanned surface vessels, to seize control of small islands and rapidly set up forward operating bases. Unmanned platforms, including drones, unmanned ships, and unmanned ground vehicles, including remotely-operated mobile artillery systems, would be important to giving these Marine units additional capabilities without the need for significant amounts of additional manpower.

Missile units, especially with anti-ship missiles, would then be able to conduct strikes on hostile ships from this constellation of island outposts. Depending on the facilities available or that could be readily made available, they might also support forward manned or unmanned aviation operations. Targeting data from forward-deployed Marine units would also be passed back to other assets, including Navy ships and U.S. Air Force aircraft, which could then conduct their own stand-off attacks.

To keep the enemy on edge and to prevent them from effectively counter-attacking, Marines would reposition from one outpost to another every 48 to 72 hours. Decoy movements, which could be physical or generated using electronic warfare systems, would further confuse the enemy. Constantly changing positions would also enable Marines to attack from different vectors, forcing an opponent to be constantly evaluating their own defenses and potentially spreading their forces thin to protect against all avenues of attack.

“The Marine Corps will have three Marine Littoral Regiments (MLRs) organized, trained, and equipped to accomplish sea denial and sea control within actively contested maritime spaces as part of a modernized III MEF [Marine Expeditionary Force],” U.S. Marine Corps Major Joshua Benson, a Marine Corps Combat Development Command spokesperson, separately told USNI News in a statement. “This Pacific posture will be augmented by three globally deployable Marine Expeditionary Units (MEUs) that possess both traditional and Expeditionary Advanced Base capabilities that can deploy with non-standard Amphibious Ready Groups.”

In principle, the EABO concept certainly presents a number of potential benefits. There are also real questions about just how viable it would be in practice, especially from a logistical standpoint.

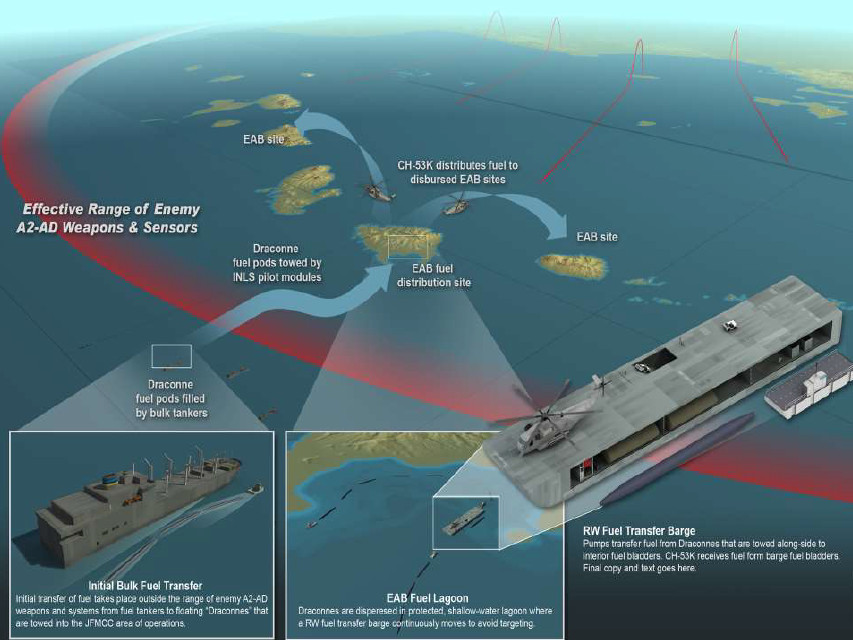

In his interview with the Journal, General Berger highlighted how 3D printing in small field workshops could help manufacture on-demand replacement parts to support distributed operations. But you can’t 3D print fuel, water, ammunition, or food. Water is a resource that U.S. military units particularly take for granted and which is absolutely essential to any operation.

The fuel demands for modern U.S. military units are also only increasing as more and more is required on a daily basis to power the generators that supply electricity for ground-based sensors, communications systems, living facilities, and more. There is work being done on alternate battlefield power concepts, including small nuclear reactors and hydrogen fuel cells, but these efforts are still in the very early stages of development.

The Marines have been looking at various distributed logistics concepts, including using unmanned ships and expendable supply drones, and even seaplanes, as ways to get critical supplies to forward units with limited risk. None of these proposals entirely eliminate supply chain disruption that could potentially have serious impacts on the ability of Marine units to operate under the EABO concept.

“Some of the capabilities we assume might pan out, will not pan out, and other technological things will come along that we have not even considered,” Berger told the Journal. He described his plan “as an aim point” and that the Corps would “monitor the threat all along as we go.”

It certainly remains to be seen how much of the Commandant’s ambitious proposal comes to fruition. However, it is clear that the Marine Corps’ present senior leadership sees radical changes as essential to ensure that the force continues to be useful in future major wars, especially in the Pacific region.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com