Turkey and Russia have cut a deal that will put a new ceasefire into place between forces aligned with Syrian dictator Bashar Al Assad and anti-regime groups in northwestern Syria. It also lays out plans for a formal buffer zone between the two sides that Turkish and Russian troops will patrol together. This follows a massive burst in fighting in Syria’s northwestern Idlib province, which, in turn, prompted a major Turkish military intervention after dozens of Turkish troops died there in airstrikes last week.

Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin, standing side-by-side, announced the agreement following a face-to-face meeting in Moscow on Mar. 5, 2020. The two leaders had agreed to meet in the aftermath of still murky airstrikes that killed at least 33 Turkish soldiers in Idlib on Feb. 27. After days of drone and artillery strikes on Assad’s forces, and increased support to Turkish-backed Syrian forces, Turkey officially launched Operation Spring Shield into northwestern Syria on Mar. 1. The Syrian regime has lost multiple fixed-wing combat jets and helicopters, dozens of armored vehicles and artillery pieces, and thousands of troops in the recent fighting.

“Considering all the recent developments, a new status quo is inevitable in Idlib,” Erdogan said at the press briefing on the agreement. “We have deployed additional military units to Syria to ensure regional stability. Our priority is to enable de-escalation in Idlib.”

“We have always solved our problems by working together,” Putin said. “Today was no different.”

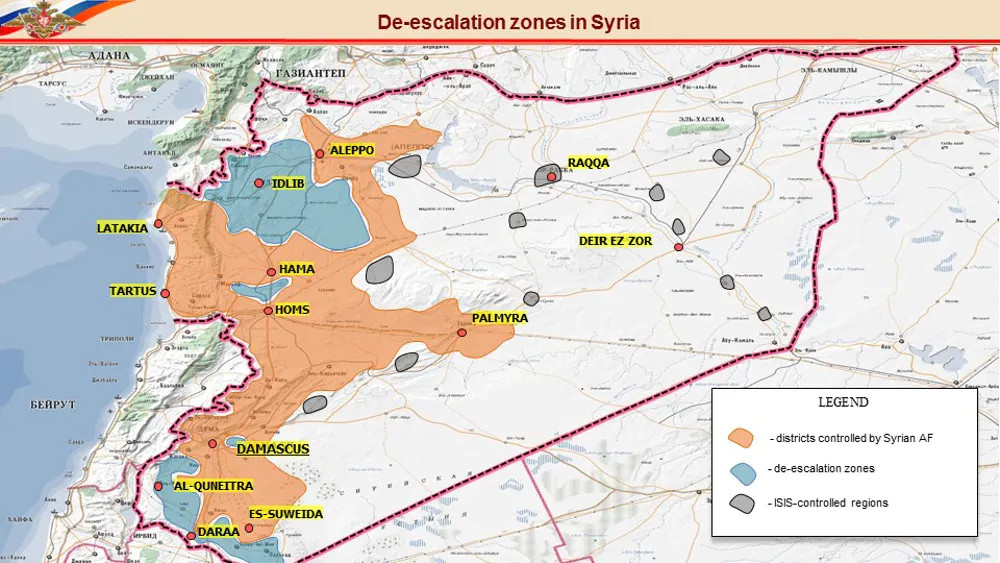

The agreement contains three major provisions, the first of which is a ceasefire which will go into effect at 12:01 AM local time on Mar. 6. This halt to “military actions” is limited to “the line of contact in the Idlib de-escalation area.” In 2017, Turkey and Russia, together with Iran, agreed to turn Idlib into an ostensibly neutral safe zone, a deal you can read about in more detail in this past War Zone piece.

The second and third provisions cover the establishment of a buffer zone that will extend six kilometers, or just under 4 miles, both north and south of the M4 highway in northwestern Syria. “Specific parameters of the functioning of the security corridor will be agreed between the Defense Ministries of the Turkish Republic and the Russian Federation within seven days,” the text of the agreement says. Turkish and Russian troops will begin actively patrolling along the M4 to enforce this corridor starting on Mar. 15.

The deal represents an immediate territorial gain for Assad, as it creats a hard front line that pushes Turkish-backed forces north of the M4 and cedes areas south of that highway, which had been part of the original de-escalation zone, to his regime. The Syrian regime also remains in control of the M5 highway, which it recently recaptured and is a major strategic route.

At the same time, the Syrian government’s ability to reassert authority over all of Idlib looks beyond reach for the forseeable future. This is despite Turkey and Russia “reaffirming their commitment to the sovereignty, independence, unity and territorial integrity of the Syrian Arab Republic” in this new agreement.

The plans for joint patrols along the western end of the M4 sound like they will mirror patrols that Turkish and Russian forces presently conduct on parts of that same highway in northeastern Syria. In October 2019, the two countries agreed to create another buffer zone along that end of the Turkish-Syrian border. This followed a unilateral Turkish intervention earlier that month that was primarily aimed at ejecting U.S.-backed predominantly Kurdish forces from that same area. For practical purposes, all of these deals have left Turkey in de facto control of a wide swath of northern Syria.

Whether or not this agreement reduces tensions and curbs the fighting in northwestern Syria, or in any way helps the millions of innocent Syrians presently caught in the middle and who are in the midst of a humanitarian catastrophe, very much remains to be seen. Fighting looks set to continue right up until the ceasefire begins.

Erdogan has also reserved his right to attack Syrian forces, or those aligned with them, in Idlib again in the future, if necessary. For his part, Assad has never given up his claim to Idlib, or any other part of Syrian territory presently under the control of foreign or foreign-backed forces.

In 2018, despite the designation of Idlib as a “de-escalation zone” the previous year, the Syrian regime, with support from Russia, moved again to recapture the province in the face of persistent attacks from Turkish-backed militants there. Another deal between Turkey and Russia brought those plans to a halt and allowed Turkish forces to establish dozens of observation posts in the region with the goal of halting further attacks from anti-regime forces. Those Turkish outposts have since become their own point of contention between Assad and the Turkish government.

The desired end to anti-regime violence emanating from Idlib never materialized and Assad has launched a number of subsequent offensives, the most recent of which began, again with Russian support, in January. Erdogan’s government, which has been staunchly opposed to Assad since the Syrian civil war began in 2011, steadily increasing its involvement in the fighting in Idlib in response, including indirect and direct support for various anti-regime groups.

An explosion in the use of shoulder-fired man-portable air defense systems, or MANPADS, against both Syrian and Russian combat aircraft flying over the region, was one particularly notable development. Armed Turkish drones, as well as F-16 Viper fighter jets, also proved to be an especially decisive factor in keeping Assad’s forces at bay.

After the airstrikes that killed the Turkish soldiers on Feb. 27, Erdogan gave Assad an ultimatum to withdraw, which was promptly ignored and led to Operation Spring Shield. It’s worth noting that Turkey and Russia both say Syria was responsible for those strikes, but there is evidence to suggest Russian jets may have actually carried them out.

Still, despite all of this, Turkey and Russia seem most interested in finding a stable status quo that meets their particular agendas. Turkey appears intent on neutering Assad’s military capabilities if it cannot secure his ouster in some way for good. Russia’s main reason for being in Syria in the first place is continued access to geopolitically strategic naval and air base facilities along the Eastern Meditterren Sea, which does not require the Syrian regime to exercise authority over any significant portion of the country.

Ergodan and Putin themselves have an obvious interest in maintaining the relations between their two countries, too. The increasingly dictatorial Erdogan has moved closer to the Russian sphere of influence in recent years and away from his NATO allies, especially the United States. The Turkish government’s purchase of Russian-made S-400 surface-to-air missile systems has caused particular strain with other members of the Alliance, even causing the U.S. government to eject Turkey from the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program.

“There is always something to talk about, but now the situation in a well-known area – Idlib – has escalated so much that it requires our direct, personal conversation,” Putin said in remarks with Erodgan before the meeting that led to the new agreement on Idlib. “We need to talk about the situation that has developed to date so that nothing like this happens again, and so that it does not destroy the Russian-Turkish relations, which I, and as I know, you too, treat very carefully.”

For the moment, that relationship has led yet another new status quo to emerge in Idlib and the rest of northwestern Syria. Unfortunately, Ergodan and Putin still face serious challenges in preserving their latest deal and the course of the Syrian conflict, as a whole, remains uncertain as ever.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com