Turkish officials have called for a no-fly zone over Syria and say they consider forces aligned with Syrian dictator Bashar Al Assad to be legitimate targets. This follows the death of at least 33 Turkish troops, and the wounding of another 32, in airstrikes in the northwestern Syrian province of Idlib, where Russian warplanes have been heavily engaged. This prompted massive retaliatory strikes from Turkey. Russia, Assad’s principal ally, has, in turn, accused Turkey of violating the terms of ceasefire deals regarding that area stretching back to 2017. A recent surge of fighting between Turkish-backed groups and the regime has already raised fears that a broader regional conflict may be emerging.

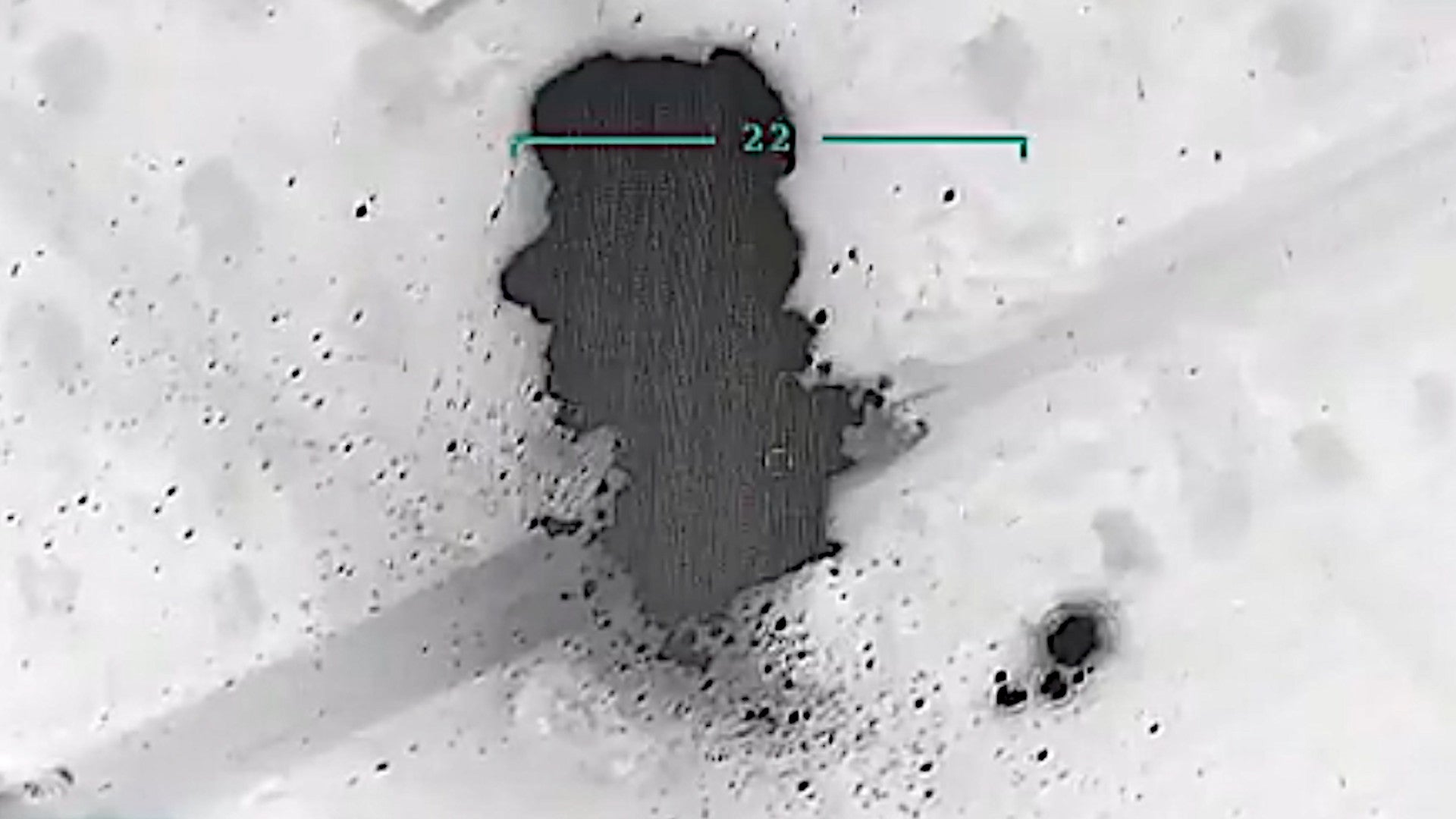

This most recent escalation in the violence began on Feb. 27, 2020, with the airstrikes that killed the Turkish troops in Idlib. The Turkish Ministry of Defense says that it responded during the night of Feb. 27-28 with its own air and artillery strikes on 200 Syrian regime targets across the northwestern portion of the country. Turkey claims that it destroyed five helicopters, 23 armored vehicles, 23 artillery pieces, one Buk-M1-2 medium-range surface-to-air missile system, and one Pantsir-S1 point defense air defense system. It also said that it killed 309 of Assad’s troops.

It’s unclear if all of these strikes occurred last night or if this tally might include strikes from earlier in the month. There were unconfirmed reports that Turkey attacked Russia’s Khmeimim Air Base outpost and it possible that anti-Assad forces launched their own attacks as the Turkish strikes were ongoing. There has little further reporting on this, increasing the likelihood that Syrian militant groups were responsible, if anything happened at all.

Turkey, together with its local partners, has been attacking regime ground and air forces for weeks now, including with armed drones, as it seeks to stem the offense in Idlib. The Turkish government has stepped up deliveries of heavier weaponry, including armored vehicles and howitzers, to various Syrian militant groups opposed to Assad, as well.

Turkey’s increasing intervention in the conflict has also included the deployment of a larger number of license-made Stinger shoulder-fired man-portable air defense systems, or MANPADS, as well as the reported deployment of vehicle-mounted systems employing the same short-range heat-seeking missile. MANPADS have brought down a number of Syrian helicopters in recent weeks. There is evidence that actual Turkish military personnel may be the ones employing them and that they may have also been trying to shoot down Russian, as well as Syrian, combat jets. Of course, MANPADS have been a feature in the Syrian conflict for years now, as well.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan told his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin that “every Syrian government unit” was a “legitimate target” during a phone call between the two leaders on Feb. 28, 2020. Earlier this month, Erdogan had threatened a massive response against Assad if any Turkish troops died in strikes in Syria. Before this large number of Turkish troops died in the airstrikes yesterday, more than a dozen of them had already been killed in the fighting in Idlib since the beginning of February.

“Millions of civilians are being bombarded by air for months now. Infrastructure, including schools and hospitals, is being targeted by the regime systematically,” Fahrettin Altun, the communications director for the Turkish presidency, who also called for the international community to establish a no-fly zone, wrote on Twitter on Feb. 28. “A genocide is happening slowly before our eyes. Those with conscious [sic; conscience] and dignity must speak up.”

The Kremlin’s official statement on Erdogan and Putin’s call says that the Russian President expressed “Serious concern about the escalation of tensions in Idlib.” It said he had also called for greater coordination between the Turkish and Russian defense ministries.

Russia “did all it could to ensure [the] security of Turkish service members,” Dmitry Peskov, Putin’s top spokesperson, told reporters later on Feb. 28. He further implied that the Turkish troops would have been fine had they confined themselves to their observation posts in Idlib. Turkey established 12 of these sites following a ceasefire deal with Syria and Russia in 2018. The three countries had already agreed to designate the province as a “de-escalation zone” the year before, this had failed to stop fighting between Assad’s forces and militants.

“None of these Turkish servicemen either suffered or came under threat at these posts,” Peskov said. “The tragic deaths of Turkish troops occurred at the places of offensive operations by terrorist formations, among which, incidentally, there are numerous foreign mercenaries, including citizens of the former Soviet Union.”

“The Turkish side did not report about the presence of Turkish forces there, despite our inquiries,” he continued. Turkish authorities have disputed this, saying that they did provide Russia with details about their force posture in Syria prior to the strikes.

It’s important to note that who carried out the strikes that killed the Turkish troops and how remains somewhat disputed itself. The Turkish government has insisted that the Syrian air force conducted the airstrikes on its forces, but reports say that combat jets that only Russia flies in Syria were also seen overhead at the time. Any airstrikes that occurred after dark would have also been beyond the capabilities of Syria’s limited air assets.

The Russian Ministry of Defense has said that Syrian artillery was to blame, according to Russian state media. It also denied that its forces were operating in the area at the time at all.

“The Syrian Army has every right to respond to repeated ceasefire violations in the Idlib zone and suppress terrorists,” Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov also said on Feb. 28. “We cannot stop the Syrian Army from implementing the provisions of U.N. Security Council resolutions on the uncompromising fight against all forms of terrorism.”

However, Russia’s air assets in Syria are infinitely more capable than those of the Syrian Air Force, which has suffered numerous losses over nearly a decade of conflict, including with other regional adversaries, and operates almost exclusively during the day. Video and pictures from observers on the ground show that Russian sorties simply outnumber those of their Syrian counterparts.

Still, this would not be the first time Turkey has blamed apparent Russian airstrikes on Assad. Turkish officials also said that the Syrian Air Force was responsible for killing its troops in an incident on Feb. 20, despite evidence to the contrary.

Fighting, including more airstrikes, has continued in Idlib, despite these various pronouncements and it’s unclear where the various parties will go from here. The Turkish government called an emergency meeting with representatives from its NATO allies on Feb. 28. Despite declarations of support for Turkey, none of the Alliance’s members, so far, appear to be moving to more actively support Ankara in the conflict.

The official statement from NATO’s Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg decried “indiscriminate airstrikes by the Syrian regime and its backer Russia,” but did not blame one party in particular for the deaths of the Turkish troops. It also called for de-escalation on all sides and a return to the provisions of the 2018 ceasefire deal.

Turkey could conceivably attempt to enforce a no-fly zone over Idlib and other areas of northwestern Syria by itself. It could also keep combat jets, such as its American-made F-16 Vipers, on routine patrols on its side of the Turkish-Syrian border, poised to chase away any intruding aircraft or conduct more retaliatory strikes on short notice, as a deterrent.

Both options do raise the risk of direct confrontations with Russia’s aircraft or air defenses in Syria. It’s certainly true that Turkey has not shied away from shooting down Russian, as well as Syrian, aircraft in the past, but there are some indications that authorities in Ankara might be more wary of being faced with the prospect of finding itself in a major aerial engagement without explicit support from its allies. It’s important to remember that Turkey has moved closer to Russia’s sphere of influence in recent years, too, including buying advanced weaponry from them in spite of protests from their NATO allies.

In a clear sign that Turkey did not get the level of support it wants now from NATO, Turkish officials have effectively removed all restrictions on the movement of Syrian refugees and other foreign migrants out of the country and many of those individuals have already begun attempting to make their way westward into Europe. Erdogan has long threatened to weaponize these groups, tapping into growing European anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim sentiments and offering to keep them contained within Turkey in exchange for various concessions. This seems to be the exact calculus for the abrupt shift in Turkish policy now.

Furthermore, last week, Turkey approached the United States about deploying batteries of Patriot surface-to-air missile systems to its southern Hatay province, which borders Idlib. This plan reportedly envisioned those air defense assets as presenting an additional deterrent to Russian and Syrian air operations across the border.

Since then, the Pentagon has said it has talked with its Turkish counterparts about possible ways the two countries, together with the international community, can cooperate on Syria, but has yet to respond publicly to the request for Patriots one way or another. U.S.-Turkish relations have been strained over a number of issues in recent years, including Ankara’s decision to purchase Russian-made S-400 air defense systems, which resulted in Turkey’s Air Force getting booted from the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program, and its unilateral intervention into northern Syrian last year.

“I hope that President Erdogan will see that we are the ally of their past and their future and they need to drop the S-400,” Kay Bailey Hutchison, the U.S. Ambassador to NATO, told reporters on Feb. 27. “They see what Russia is, they see what they’re doing now, and if they are attacking Turkish troops, then that should outweigh everything else that is happening between Turkey and Russia.”

Turkey continues to refuse to get rid of the S-400s, which are slated to become operational in April. At which time it is possible that they could, ironically, deploy them to the border areas to challenge Russian and Syrian aerial activity, as well.

U.S. Senator Lindsey Graham, a South Carolina Republican and close ally of President Donald Trump, who himself has a good relationship with Erdogan, has called for a no-fly zone in Syria, as well. Trump has called on Assad, and its Russian allies, to halt their offensive in Idlib, but he has repeatedly expressed his desire to disengage the United States from the Syrian conflict, too. It seems unlikely that the U.S. government, broadly, is interested in putting itself in a position where it would explicitly be threatening to shoot down Russian aircraft, either.

Turkey’s military resources are also increasingly strained as Erdogan has pursued a more assertive foreign policy. While Turkish troops have been increasingly dying in Idlib, casualties are also mounting among the country’s forces in Libya, another expanding conflict that the War Zone

It’s also worth pointing out that while Turkey and Russia appear to be embroiled in low-level conflict in northeastern Syria already, the two countries continue to conduct joint military patrols along a buffer zone in northeastern Syria. Ankara and Moscow both see these operations as essential to their respective agendas of keeping Kurdish groups in check and challenging a dwindling American military presence in that region.

A collapse in Turkish-Russian ties would upend all that, something that neither side seems interesting in allowing to happen. Preparations are now underway for a meeting between Erdogan and Putin over Idlib in March.

At the same time, neither Assad nor Turkey seems inclined to back down over control of Idlib, the last major bastion of anti-regime forces in northwestern Syria. As the fighting continues the risks of further errors in judgment and miscalculations, ones that might be too big to simply explain away by blaming the regime in Damascus, will only increase. As noted, there is evidence that Turkish forces on the ground have been trying to shoot down Russian combat jets, as well as Syrian military aircraft and helicopters.

This, in turn, raises the possibility of an overt confrontation between Turkey and Russia, which could quickly spiral into a larger regional conflagration.

UPDATE: 9:40pm EST

A U.S. State Department official has told reporters that the United States is now looking at ways to support Turkey with regards to the situation in Idlib, but that there are no plans to send any U.S. troops or Patriot surface-to-air missile systems. When it comes to the Patriots, the official said that there were simply none of these air defense systems available at present for such a deployment, an issue that The War Zone

had previously noted might come up. The U.S. government could look to increase intelligence sharing or at providing logistical or other non-combat support to Turkey.

In addition, the State Department official did not specifically blame Russia for the airstrikes that killed the Turkish troops in Idlib on Feb. 27. However, they did say the idea that the Syrian Air Force was making any meaningful contributions to the air campaign in Idlib it was “laughable.”

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com