Boeing has announced that it recently conducted an experiment together with the Navy in which an EA-18G Growler electronic warfare aircraft oversaw two other EA-18Gs flying missions semi-autonomously. The test demonstrated technology that would allow the service’s Growlers, as well as its F/A-18E/F Super Hornets, to work closely together with unmanned aircraft and could also point to a future pilot-optional capability for these combat jets.

The Chicago-headquartered plane maker revealed the tests had occurred in a press release on Feb. 4, 2020, but did not say when they had taken place. The company did say that the Growlers had operated from Naval Air Station Patuxent River, one of the Navy’s premier aviation test facilities and home of Naval Air Systems Command, and that the sorties had been part of the Navy Warfare Development Command’s annual fleet experiment (FLEX) exercises.

“This demonstration allows Boeing and the Navy the opportunity to analyze the data collected and decide where to make investments in future technologies,” Tom Brandt, the firm’s Manned-Unmanned Teaming demonstration lead, said in a statement. “It could provide synergy with other U.S. Navy unmanned systems in development across the spectrum and in other services.”

“This technology allows the Navy to extend the reach of sensors while keeping manned aircraft out of harm’s way,” he continued. “It’s a force multiplier that enables a single aircrew to control multiple aircraft without greatly increasing workload. It has the potential to increase survivability as well as situational awareness.”

Boeing says that the experiments consisted of a total of four flights, during which the three EA-18Gs performed 21 “demonstration missions,” in total. The company did not say what these entailed. Given the Growler’s primary mission set, they may have involved simulated electronic warfare sorties against mock threats, as well as simply showing off the ability of the EA-18G operating as the “mission controller” to direct and otherwise coordinate the activities of the other two semi-autonomous aircraft.

There were pilots on board the two Growlers that flew semi-autonomous during the experiments, with those personnel performing the take offs and landings and otherwise acting as backups in case of system failures, according to Military.com. It’s also unclear if the Navy is specifically interested in a pilot-optional capability for the EA-18G or was simply using these test flights as an opportunity to explore manned-unmanned concepts, in general.

When it comes to electronic warfare, the general concept that Boeing demonstrated during these recent tests makes good sense. Modern air defense systems and the sensors that support them, especially those in service or in development among “great power” competitors such as Russia and China, are increasingly more capable and have longer ranges.

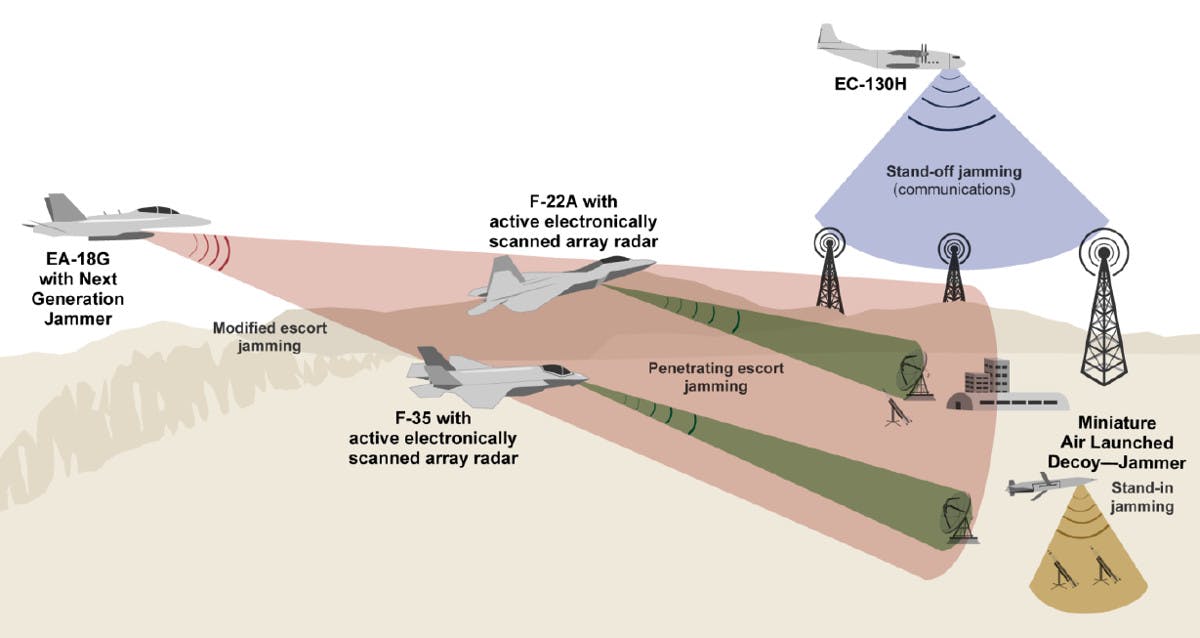

This, in turn, presents ever-growing threats to the non-stealthy EA-18Gs, especially in future operations where they might be called upon to support stealth platforms, such as F-35 Joint Strike Fighters. The Navy already expects the Growlers to perform their primary missions from a standoff distance, but this may not be enough to keep the aircraft adequately shielded from potential threats as time goes on.

Linking the jets together with small groups of unmanned platforms with their own sensors and electronic warfare packages would enable the manned aircraft to detect and classify threats, as well as potentially engage them, from further away. The teams of pilotless aircraft could also cover a much broader area at once, while still reducing the risks to actual pilots.

Back in 2017, the Navy had announced it was working with Northrop Grumman on developing swarms of very small drones carrying electronic warfare or other payloads that EA-18Gs could deploy using modified air-launched canisters typically used for cluster munitions. The Navy has also demonstrated the ability of F/A-18E/F Super Hornets to deploy drone swarms that could confuse or distract hostile air defenses, among other possible missions, in the past, as seen in the video below.

Of course, these latest manned-unmanned tests may not necessarily be related specifically to the electronic warfare mission, which is ever-more distributed, including through the development of expendable non-kinetic munitions, and increasingly does not necessarily require a highly complex and expensive dedicated platform, such as the EA-18G. The Navy, specifically, has spent the better part of the last decade, at least, exploring and developing components for an over-arching, distributed, multi-platform electronic warfare architecture. The War Zone was first to report on the full extent of this program, known as Netted Emulation of Multi-Element Signature against Integrated Sensors (NEMSIS), which you can read about in much greater detail here.

The EA-18Gs at Patuxent River may simply have been the platforms available with the most appropriate existing systems installed to conduct the tests, which might be focused more on broader developments with regards to ‘loyal wingman’ type drones and largely-autonomous unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAV). Simply turning existing combat jets into pilot-optional platforms would certainly offer a low-cost, low-risk path to a UCAV, albeit an unoptimized one with significantly limited capabilities compared to a design that does not need to in any way account for a pilot being onboard.

In 2016, the U.S. Marine Corps notably conducted its own test involving an AV-8B Harrier jump jet flying together with a Kratos Unmanned Tactical Aerial Platform-22 (UTAP-22), also known as a Mako, acting as a “loyal wingman.” The AV-8B employed the Tactical Targeting Network Technology (TTNT) high-bandwidth data link during that experiment to exchange information and instructions with the UTAP-22. The EA-18G was the first aircraft to carry the TTNT system, which is now also now being integrated into the Navy’s Block III F/A-18E/F Super Hornets.

All of this also comes as Boeing is continuing to develop the MQ-25A Stingray, a drone tanker that is set to be the first operational unmanned aircraft to join the Navy’s Carrier Air Wings and which could take on additional missions in the future. The service is also in the midst of re-examining what the next generation of naval combat aircraft might look like and what mix of manned and unmanned platforms may be the most optimal, something War Zone has previously covered in-depth.

The MQ-25 program itself is as much about proving the concept of unmanned carrier aviation and developing the required infrastructure on the Navy’s carriers to support those operations as it is about the tanking mission itself. The service is in the process of installing drone control centers on its carriers now as they go through normal overhaul and maintenance periods, which it already says could support the fielding of additional unmanned platforms after the Stingray.

In 2019, Boeing’s Australian subsidiary also conducted an experiment using a pair of jet-powered surrogate drones to demonstrate semi-autonomous teamed flight. This was in support of the company’s separate work on a new loyal wingman drone for the Royal Australian Air Force.

Of course, this is certainly not the first time a branch of the U.S. military has demonstrated these types of manned-unmanned teaming capabilities. In 2015, the U.S. Air Force conducted a very similar test, known as Have Raider, involving a manned F-16D Viper fighter jet working with another, unmanned F-16. Two years later, as part of the follow-on Have Raider II experiment, the pilotless Viper actually broke formation with its manned counterpart, flew a pre-determined route, and then rendezvoused again with the F-16D.

The reality is that the U.S. military, together with various defense contractors, notably including Boeing, already proved that semi-autonomous and autonomous UCAVs could work cooperatively with minimal human interaction nearly two decades ago. These UCAVs represented the biggest leap in air combat since the jet engine before they totally disappeared from the Air Force’s plans and nomenclature and got peculiarly passed over by the Navy.

You can read all about this bizarre and puzzling history and its consequences in this past special feature of ours. With this in mind, the Growler tests simply add to the already substantial mountain of evidence underscoring the validity and feasibility of these concepts, raising the question of why these capabilities still remain almost completely confined to experimental settings or the realm of deep classification.

Hopefully, Boeing and the Navy will release more information about these latest Growler tests at Patuxent River and their objectives soon.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com