Publicly available data suggests that a Russian inspector satellite has shifted its position in orbit to bring it relatively close to a U.S. KH-11 spy satellite. Russia has a number of what it calls “space apparatus inspectors” in orbit, which the U.S. government and others warn the Kremlin could use to gather intelligence on other satellites or function as “killer satellites,” using various means to damage, disable, or destroy those targets.

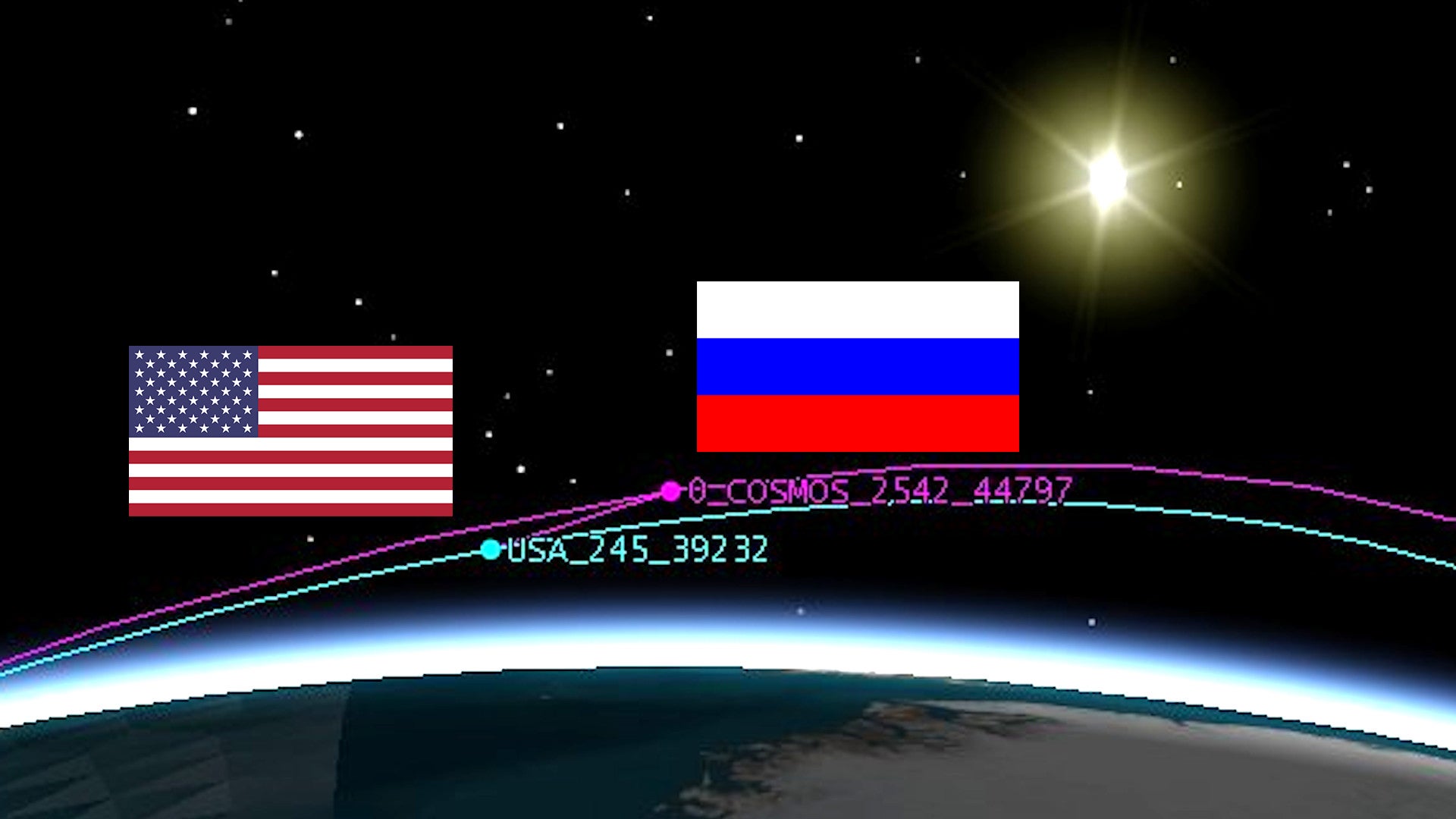

On Jan. 30, 2020, Michael Thompson, a graduate student at Purdue University focusing on astrodynamics, posted a detailed thread on Twitter about the Russian inspector satellite Cosmos 2542, also written Kosmos 2542, appearing to synchronize its orbit with a U.S. satellite known as USA 245, which is understood be one of the National Reconnaissance Office’s KH-11 image gathering spy satellites. Russia launched this particular satellite from the Plesetsk Cosmodrome on Nov. 25, 2019, according to Space-Track.org, a U.S. government website that provides public data on space launches from the U.S. military’s Combined Space Operations Center and the U.S.-Canadian North American Aerospace Defense Command. This is just one of a number of space apparatus inspectors and other curious satellites that the Kremlin has put into orbit over the past decade.

“This is all circumstantial evidence, but there are a hell of a lot of circumstances that make it look like a known Russian inspection satellite is currently inspecting a known US spy satellite,” Thompson wrote. “A pretty thorough look of the satellite catalog can’t produce another potential target that looks as good as this in terms of the orbits and viewing geometry.”

Starting on Jan. 20, 2020, Cosmos 2542 had conducted a series of maneuvers to change its position and timing to match USA 245’s “orbital period.” The Russian satellite had previously been circling the planet in the same plane as its American counterpart, Thompson explained, but in such a way that the two only came relatively close to each other once every 11 to 12 days.

“Note that any two satellites in the same plane with offset periods will have passes like this at some regular cadence,” Thomspon added. “It’s enough to raise suspicion, but not prove anything.”

However, how Cosmos 2542 is orbiting now means that it now has a “consistent view” of USA 245. “As I’m typing this, that offset distance shifts between 150 and 300km depending on the location in the orbit,” according to Thompson.

A spacing of 150 to 300 kilometers, or between 93 and just short of 186 and a half miles, may not seem “close” by terrestrial standards, but it is for objects circling Earth in the vacuum of space at speeds of thousands of miles per hour. “The relative orbit is actually pretty cleverly designed, where Cosmos 2542 can observe one side of the KH11 when both satellites first come into sunlight, and by the time they enter eclipse, it has migrated to the other side,” Thompson Tweeted, meaning that the Russian satellite has the potential opportunity to observe both sides of USA 245.

Cosmos 2542 had already been involved in other curious activities since its launch in November 2019. On Dec. 6, 2019, Russia announced that it had deployed another smaller satellite, dubbed Cosmos 2543, while in orbit. Nico Janssen, another satellite observer, noted that USA 245 had shifted its own orbit between Dec. 9 and Dec. 10, possibly to prevent a collision with Cosmos 2543, according to RussianSpaceWeb.com. Janssen had also noted that Cosmos 2542 had synchronized its orbit with the American spy satellite.

It’s still unclear what, if anything, in particular, Cosmos 2542 might actually be doing in this new orbit. One possibility is that it could be using onboard systems, such as cameras or other sensors, to gather information about the KH-11, the capabilities of which are highly classified. The Russian Ministry of Defense has said that the satellites exact capabilities are classified, but Interfax reported that its cameras are also capable of Earth imaging, in addition to monitoring other satellites in the inspector role, according to RussianSpaceWeb.com.

Thompson questioned the intelligence value of visually observing the exterior of the American satellite, pointing out that publicly available information has already allowed for good estimates as to the basic imaging capabilities of these spy satellites, the first variations of which entered service in the 1970s. Of course, USA 245 was last of the most modern KH-11 Block IV satellites, also known as the Evolved Enhanced CRYSTAL System, to be launched and there may still be value in examining it externally. It may also be possible to gather electronic or signals intelligence data that could be of additional value.

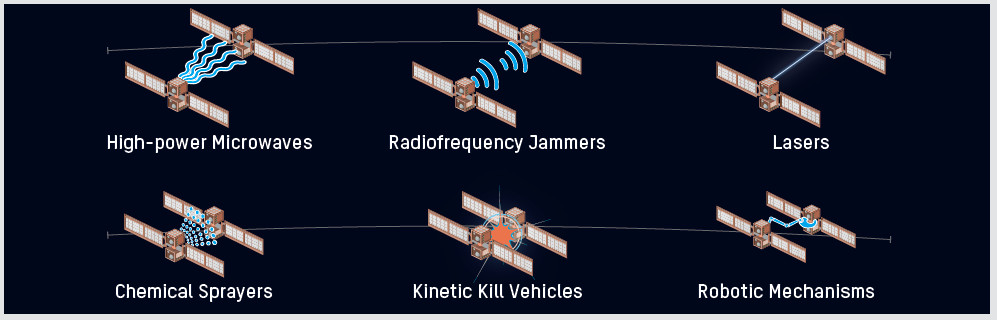

Beyond that, the ability of Cosmos 2542 to get into this position at all is notable and is exactly the kind of orbital maneuvering that the U.S. government had pointed to in the past evidence of potential “killer satellites.” A highly maneuverable, but small satellite could possibly get close enough to disrupt the operation of, disable, or destroy another object in space using a variety of means, ranging from electronic warfare jammers to directed energy weapons, such as a laser.

When it comes to spy satellites, it might be possible to just spray chemicals or other materials that blind or otherwise damage the lenses on their cameras. A low power laser could also blind optics persistently if the attack satellite were to be able to get in a good position. A killer satellite could also just simply smash into its intended target to try to damage or destroy it.

Russia insists that its inspector satellites are only in orbit for their ostensible mission of being available to get close to the country’s other space-based systems and examine them if they break down or otherwise malfunction. However, Thompson notes that the only other satellites in this particular plane are Cosmos 2523, Cosmos 2543, and the Russian commercial remote sensing satellite Resurs-P1. Cosmos 2523 is another inspector satellite. Cosmos 2523 is also part of a group of Russian satellites that observers have previously watched perform various curious maneuvers back in 2018, as well.

Whatever Cosmos 2542 is or isn’t doing, its present position is clearly deliberate and it is hard to see how it would not be related in some way to the position of USA 245. It is worth noting that this is hardly the first time similar confluences in orbit have occurred and that observers have spotted U.S. satellites possibly examining foreign satellites in the past, as well.

Russia is known to be interested in anti-satellite capacities and has developed or is developing a number of terrestrial anti-satellite weapons, including ground-based and air-launched interceptors, too. China is pursuing similar developments, as well. The appearance of Cosmos 2542 in its new orbit also comes as the U.S. military is very publicly working to address concerns about the increasing vulnerability of various space-based systems that it relies on heavily.

These space-based capabilities range from space-based early-warning systems to intelligence gathering platforms such as the KH-11 to satellites supporting navigation and communications, all of which would absolutely critical in any potential future conflict. The most obvious expression of this recent push is the creation of U.S. Space Force, an entirely new branch of the U.S. military to focus on American military activities in and related to space, as well as the procurement of satellites and other related systems and infrastructure.

One of Space Force’s immediate tasks will be to simply craft an understanding of what a future war in space might actually look like, which is an ever-increasingly realistic prospect, as The War Zone

has highlighted on numerous occasions in the past. Despite this reality, basic definitions of what a conflict in space might entail and how the U.S. might act in response, including possible shows of force or direct retaliation, significant issues that The War Zone has also previously examined in-depth.

“There may come a point where we demonstrate some of our capabilities so that our adversaries understand they cannot deny us the use of space without consequence,” then-Secretary of the Air Force Heather Wilson had said at the Space Foundation’s 35th annual Space Symposium in 2019. It remains unclear exactly what she meant, but her comments certainly indicated an increasingly tense environment for the U.S. military in space.

“The central point is that we need a cadre of people who grow up and spend their whole careers learning and thinking: ‘how we dogfight in space,'” Air Force Major General Clinton Crosier, the Deputy to the service’s Deputy Chief of Staff for Strategy, Integration, and Requirements, said at RAND Corporation think tank event in 2019. “Our adversaries have things on orbit that are looking at ways to do harm to our systems.”

U.S. military officials and politicians have also called for the declassification of more information about U.S. military space capabilities, which could potentially help explain what options may be available to deter or respond to potential threats in orbit. “In many cases in the Department [of Defense], we’re just so overclassified it’s ridiculous, just unbelievably ridiculous,” U.S. Air Force General John Hyten, the present Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said at a recent Air Force Association gathering, speaking broadly about classification issues, according to Defense News.

How to react to the activities of foreign satellites, such as Cosmos 2542, where it may not be clear what the threat is, or if there even is one, is exactly the kind of issue that the U.S. military, and the new Space Force, in particular, will only increasingly be faced with as time goes on.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com