A Lockheed Martin job posting has offered new details about the design and development schedule of a tactical, ground-launched hypersonic weapon that the U.S. Army and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency are working on together. The company won the contract to proceed to the third phase of this program, known as Operational Fires, or OpFires, two weeks ago.

Steve Trimble, Aviation Week‘s defense editor and good friend of The War Zone spotted the job opening for a “Staff SRM [solid rocket motor] Propulsion Engineer” at Lockheed Martin’s facility in Grand Prairie, Texas, on Jan. 20, 2020, and shared it on Twitter. The posting itself is dated Dec. 17, 2019. This was in advance of the Maryland-headquartered defense giant officially getting the Phase 3 OpFires contract, worth just under $32 million, on Jan. 10. Phase 1 had wrapped up in 2019 and Phase 2, which involves further development and testing of various components of the system, is ongoing now. Phase 3 will involve Lockheed Martin integrating the various pieces into a complete weapon system and conducting an end-to-end test, presently scheduled to take place in 2022.

“The [OpFires] Program will be entering Phase 3, Weapon System Integration and Demonstration Phase, a three-phase effort for integrated system design, development, and flight test,” the job listing says. “The propulsion engineer will need to have the ability to work with different suppliers, including the ability to evaluate the designs and technologies of motors in the 32-inch diameter size, and make recommendations for down-select on both rocket motor stages to both internal and external (DARPA) customers.”

The intended “payload” in the OpFires system will be an unpowered hypersonic boost-glide vehicle. The rocket booster will propel it to an optimal altitude and speed, after which it will glide in a relatively level trajectory inside the atmosphere to its target at extremely high speeds.

The job posting further explains that Phase 3 will include two separate competitions to pick solid-fuel rocket motors for both the first and the second stage of the Lockheed Martin’s OpFires weapon design. It says that the first stage will have a traditional rocket motor, while the second stage will feature one with throttleable thrust.

“The second stage motor development has been ongoing for DARPA as part of their Phase 2 activity, and the continued development of the second stage will transfer to Lockheed Martin oversight during Phase 3a – with a down-select of the current 3 designs,” Lockheed Martin’s job notice says. In October 2019, DARPA released video footage that showed subscale rocket motor tests that Aerojet Rocketdyne, a team consisting of Exquadrum and Dynetics, and the Sierra Nevada Corporation had conducted as part of Phase 1.

Outwardly, OpFires is similar, in broad strokes, to the Long Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW), another road-mobile system that the Army is developing separately in cooperation with the U.S. Air Force and Navy, which you can read about in more detail in this past War Zone story. However, the LRHW will use the Common Hypersonic Glide Body (C-HGB), a conical, unpowered hypersonic boost-glide vehicle, as its warhead. The Air Force’s air-launched AGM-183A Air-launched Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW) and the Navy’s submarine-launched Intermediate-Range Conventional Prompt Strike (IR-CPS) weapon will also use this joint-service boost-glide vehicle.

OpFires will use its two-stage rocket to launch DARPA’s Tactical Boost Glide (TBG) hypersonic boost-glide vehicle, instead. TBG is a more complex half-cone design, which aims to be faster, more maneuverable, and have greater accuracy than the C-HGB.

Ostensibly, the general mission of OpFires is similar to that of LRHW, as well. The goal of the road-mobile OpFires is to provide valuable long-range strike capability, especially against time-sensitive targets. The range and speed that a hypersonic boost-glide vehicle offers, as well as its ability to maneuver in the atmosphere to dodge defenses and otherwise hit targets from unpredictable vectors, present obvious benefits to commanders on the ground. DARPA has said in the past, that the TBG vehicle could have a maximum speed of up to Mach 20, giving it the ability to hit opponents thousands of miles away in a matter of minutes.

OpFires promises to be more capable and flexible than LRHW, because of the half-cone hypersonic boost-glide vehicle and, perhaps more importantly, the throttleable rocket motor. This is significant because the ability to throttle back the second-stage rocket motor means that this weapon system could have a shorter minimum range, meaning it could engage threats closer to the launch site, as well as a broader overall engagement envelope. Being able to hit widely different ranges with extreme speed and accuracy with the same weapon system would be very useful in a variety of operational scenarios, especially in any future distributed operations, where friendly forces may be situated across an especially broad area.

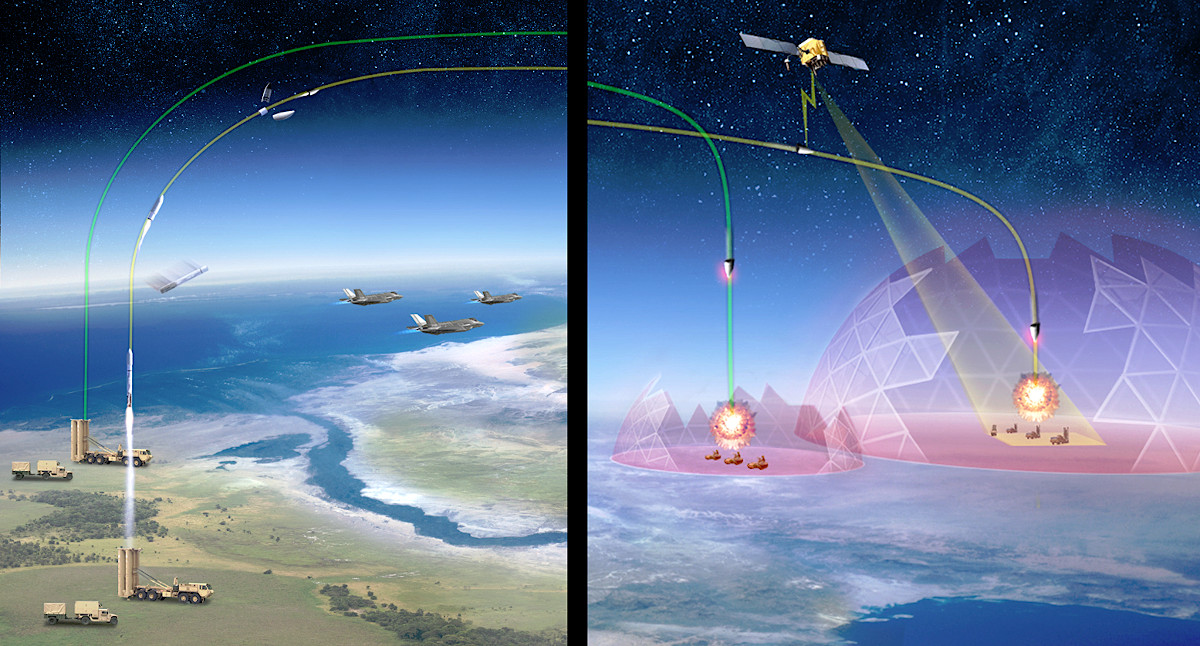

One of the most readily apparent uses for OpFires would be as a ground-based tool to suppress or destroy hostile air and missiles defenses, mission sets also referred to as SEAD/DEAD, clearing the way for follow-on strikes by friendly aircraft and air-, sea-, or ground-launched missiles. Though any asset can perform this mission, aircraft and cruise missiles are the tools the U.S. most commonly employs for SEAD/DEAD operations. Using aircraft is inherently risky, even for modern stealth combat aircraft with standoff weapons, and existing cruise missiles are also slower and more vulnerable to hostile defenses than future systems, such as OpFires.

The Army is already exploring how it might be able to use existing and future stand-off ground-based strike capabilities to assist in this mission using targeting information from aerial platforms, including the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, which you can read about in much greater detail in this past War Zone piece. OpFires concept art, seen earlier in this story, shows the use of space-based sensors for standoff targeting, as well.

Phase 2 of OpFires is set to wrap up later this year, after which Lockheed Martin will begin Phase 3 and start actively testing various components and subsystems, including the chosen first and second-stage rocket motors. Those tests are set to continue into 2021 and lead to a Critical Design Review, after which, DARPA and the Army hope that the final design will be ready for actual flight testing in 2022. This is also when the Army intends to test the LRHW for the first time, though the service is planning to rush that system into service, at least to a limited degree, by 2023. When OpFires might actually become operational is unclear.

All of this comes amid a massive surge, in general, in the development of hypersonic weapons across the U.S. military, as well as among potential opponents, such as Russia and China. Still, OpFires is an especially interesting program that promises unique capabilities and flexibility over other hypersonic weapons that the United States has in the works.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com