The possibility that Turkish troops may intervene directly in Libya’s simmer civil war is growing after lawmakers in Ankara approved a military cooperation deal that President Recep Tayyip Erdogan signed with his Libyan counterpart Prime Minister Fayez Al Sarraj last month. This reflects Turkey’s apparent growing geopolitical ambitions, which have also recently prompted a crisis over maritime boundaries and resource rights in the Eastern Mediterranean and is inflaming a growing divide with traditional allies, chiefly the United States.

On Dec. 16, 2019, Turkey’s parliament approved the agreement that Erdogan and Sarraj had signed on Nov. 27 in Istanbul. This deal reaffirmed the Turkish government’s commitment to providing military assistance and materiel support to the internationally-recognized Government of National According (GNA) based in Tripoli. It also leaves open the possibility for the Turkish military to deploy its own “quick reaction force” in direct support of the GNA. The Turkish and Libyan leaders had met again in Turkey on Dec. 15, but there has been no official announcement of the impending arrival of Turkish troops in the North African country.

“We will be protecting the rights of Libya and Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean,” Erdogan had said on Turkey’s A Haber television network on Dec. 15. “We are more than ready to give whatever support necessary to Libya.”

The Turkish President had also decried Libyan strongman Khalifa Haftar, who as “not a legitimate leader” and “representative of an illegal structure.” Haftar has been leading a challenge to the GNA from his main base of operations in the eastern Libyan city of Benghazi for years now. Forces aligned with his Libyan National Army (LNA), with support from Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and Russia, control much of the country. You can read more about Haftar and the origins of the current Libyan conflict in this past War Zone piece.

On Dec. 12, 2019, Haftar had announced a new offensive aimed at taking control of Tripoli and ousting Sarraj and the GNA. The LNA had tried and failed to do the same in April.

“Today we announce the decisive battle and the advancement towards the heart of the capital to set it free … advance now our heroes,” Haftar had declared in a televised speech carried on Saudi Arabia’s Al Arabiya television network.

Haftar claims that the LNA is the country’s legitimate military and that he is simply fighting terrorists and Islamist militants on behalf of the central government. At the same time, however, he has also disputed the GNA’s authority, saying that they are in league with the same terrorists and militants he says he is fighting, and clearly has designs on running the country.

Turkey’s growing role in Libya’s civil war

Libya has been in a state of near-constant civil conflict since a NATO-led intervention enabled rebels to unseat and kill long-time Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi in 2011. The GNA, which came into being following a United Nations-brokered deal in 2015, continues to enjoy the ostensible support of most of the international community, including the United States and major Western European powers, such as France.

Turkey, however, has emerged more recently as one of the GNA’s most active and ardent supporters. On Dec. 13, the day after Haftar announced his new offensive and before Turkish legislators had even approved the new deal with Libya, a Boeing 747-412 cargo aircraft, which belonged to Moldovan charter service Aerotranscargo, flew from Istanbul to Misrata, a city to the East of Tripoli under GNA control.

Observers and experts widely believed that this plane was carrying a mix of weapons, ammunition, and other military equipment bound for GNA forces. In addition, plane watchers using only tracking software spotted what might have been a Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2 unmanned aircraft, which can be configured to carry weapons, heading toward Misrata, as well.

The LNA promptly launched an airstrike on the Misrata airport, which appeared to target a pair of hangars where arms, ammunition, and equipment could have been stored. Unconfirmed video purporting to depict the aftermath of those strikes shows a large fire at the airport.

Also on Dec. 13, 2019, the LNA claimed to have shot down another TB2 near Tripoli.

Libya has technically remained under a U.N. arms embargo, but a recent report from that international organization has found that foreign supporters of both the GNA and the LNA have flaunted it repeatedly. In May 2019, following Haftar’s failed offensive to take Tripoli, the Turkish government began visibly supplying the GNA with various weapons, ammunition, and other military equipment. This also notably included shipments of Bayraktar TB2s, as well as BMC Kirpi mine-protected wheeled armored vehicles.

Drones have become an increasingly important feature on both sides of the Libyan conflict. The Chinese-made Wing Loong family of unmanned aircraft, a rough analog the U.S. MQ-1 Predator and MQ-9 Reaper, which came by way of the United Arab Emirates along with manned IOMAX AT-802i armed crop dusters, have supported the LNA since 2016.

The importance of drones has only increased as the availability of manned aircraft to both sides, such as GNA Mirage F1s and LNA MiG-23s, has steadily dropped as they have become increasingly difficult to operate and maintain. Anti-aircraft fire has claimed a number of these jets over the years, too.

Possibility of Turkish troops on the ground

If Turkey were to deploy actual troops to Libya, it would represent a significant escalation in its participation in the conflict. Both the GNA and the LNA have employed mercenaries over the years, but the overt presence of actual foreign forces fighting on one side or another would be a marked change in the character of the fighting, in general.

However, there are indications that things have been trending in this direction in recent months. Last year, reports first began to emerge claiming that the shadowy Russian private military company Wagner, which has strong ties, if not more direct links, to Russia’s intelligence services, had sent personnel to support Haftar. The rogue Libyan general has been actively courting Kremlin support for at least two years now and the U.S. government has accused actual Russian troops, in addition to the Wagner forces, of taking part in the conflict on his behalf this year.

“So this is something we’ve been talking about for some time, but it is Russian regulars and the Wagner forces that are being deployed in significant numbers on the ground and support of the LNA,” U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs David Schenker told reporters on Nov. 26, 2019. “We think this is incredibly destabilizing.”

The United Nations has also accused Sudan’s Rapid Security Forces (RSF) of deploying 1,000 personnel to Libya to support the LNA, possibly in coordination with Russian government forces or Wagner mercenaries. The RSF is best known for overseeing the notoriously brutal Janjaweed militias, accused of numerous atrocities while fighting rebels in Sudan’s Darfur region. It has also been responsible for violently suppressing renewed protests against the country’s new military junta that took power after it ousted long-time dictator Omar Al Bashir in April 2019 following major public demonstrations. Wagner was also linked to efforts to keep Bashir in power.

Needless to say, the possibility of Turkish troops finding themselves fighting directly against the LNA, as well as its foreign mercenaries, and any actual troops Hafter’s international backers may have sent covertly, raises the real possibility that the conflict could enter an entirely new phase and have impacts well beyond Libya’s borders.

U.S. involvement in Libya

That same kind of risk calculous may have been a factor in the U.S. military’s decision to order special operations forces to evacuate from an area to the west of Tripoli via a U.S. Navy Landing Craft Air Cushion (LCAC) hovercraft in the face of LNA advances in April. The United States has continued to operate within Libya amid the country’s unrest since 2011, with the main focuses at present being containing the spread of ISIS’ Libyan franchise and other terrorist groups, as well as hunting down individuals linked to the infamous attack on the U.S. consulate in Benghazi in 2012.

American personnel operate from a number of forward locations in the country in both GNA- and LNA-controlled territory in support of these missions and have at least appeared to try to deconflict on some level with Haftar’s forces in the past. In November, the LNA admitted that it had shot down an American drone flying over Tripoli, but said it had done so accidentally. U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) subsequently said that it believed a Russian-supplied air defense system was responsible for the shoot-down, thought it could not say whether Russian mercenaries were operating it at the time.

They “didn’t know it was a U.S. remotely piloted aircraft when they fired on it,” U.S. Army General Stephen Townsend, head of AFRICOM, told Reuters earlier in December, adding that the incident has apparently caused some strain between the U.S. military and the LNA. “But they certainly know who it belongs to now and they are refusing to return it. They say they don’t know where it is but I am not buying it.”

There have been rumors that U.S. forces or diplomatic staff have withdrawn from Tripoli, via LCAC, from the same location as they were in April. Given the identical details, this may just be a mistaken re-report of the earlier news.

In addition, C-17A Globemaster III airlifters were seen on online flight tracking software appearing to fly routes to and from Benghazi for unclear reasons. U.S. Africa Command’s public affairs office said that there have been no evacuations or “relocations,” the term it used to describe the movement of forces near Tripoli in April, in response to recent events.

The U.S. State Department’s press office also declined to say whether or not any of its personnel had left Libya recently. However, the U.S. Embassy in Tripoli has been shuttered indefinitely since 2014 in light of the country’s unstable security situation.

There have also been questions in the past about whether the United States might, despite its public pronouncements of continued support for the GNA, be looking to change tack and back Haftar instead. There were reports in April that President Donald Trump and his administration had given at least tacit approval to the LNA’s offensive toward Tripoli. The U.S. government did change tack, but has continued to engage directly with Haftar and the LNA, ostensibly in an attempt to resolve the conflict.

Whether or not the West, in general, remains committed to the GNA also came up when its forces captured U.S.-made Javelin anti-tank guided missiles, along with Chinese-made guided artillery shells, purportedly from LNA units. France later claimed these that weapons belonged to its forces in the country, but that they were inoperable and had been awaiting destruction. The apparent extremely close proximity of French elements to LNA forces raised questions about whether officials in Paris were playing both sides of the conflict.

A Mediterranean maritime boundary crisis

Regardless, the conflict in Libya has already had larger international impacts when it comes to humanitarian issues and there is already evidence that the new deal between Ankara and Tripoli may have serious and broader second-order effects. Beyond the security cooperation components, the agreement between the two countries formalizes a bilateral agreement on maritime boundaries in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The Turkish government sees the arrangement as giving it sole rights to exploit natural gas resources in one particular area. Egypt, Israel, Greece, and Cyprus, to varying degrees, see it as infringing both on their sovereign territory and their own exclusive economic zones, in violation of international law. It could also effectively block plans for a massive undersea Eastern Mediterranean gas pipeline that would connect Levantine countries, such as Israel and Lebanon, with Cyrpus and Greece, and, by extension, the rest of Europe.

“Egypt, Israel, Greece, and Cyprus cannot carry out excavations in the Mediterranean without the permission of Turkey,” Turkish President Erdogan said during an interview with the Turkish TRT television network in November. ”We will protect our maritime borders in accordance with international agreements, thus protecting our rights and the rights of the Turkish part of Cyprus.”

It’s not clear if Libyan Prime Minister Sarraj agreed to these provisions to ensure the promise of Turkish military support, but the arrangement has infuriated all of the other countries that have claims in the region. Egypt staged a major maritime drill in response, which included a demonstration of its Soviet-era, Chinese-built, American-upgraded Romeo class diesel-electric submarines and their ability to launch UGM-84 Harpoon anti-ship missiles. Greece has expelled Libya’s ambassador to the country in protest. The European Union, of which Greece and Cyprus are members, has also criticized the deal. The entire situation looks set to be, at best, a protracted legal dispute, akin broadly to challenges in international courts to China’s claims to the vast majority of the South China Sea.

Aggressive Turkish foreign policy

All told, Turkey’s recent decisions regarding Libya reflect its increasingly assertive and unilateral foreign policy, overall. Erdogan has already demonstrated his willingness to both ignore and outright act against the geopolitical interests of traditional Turkish allies, such as the United States, with little apparent regard for the ramifications.

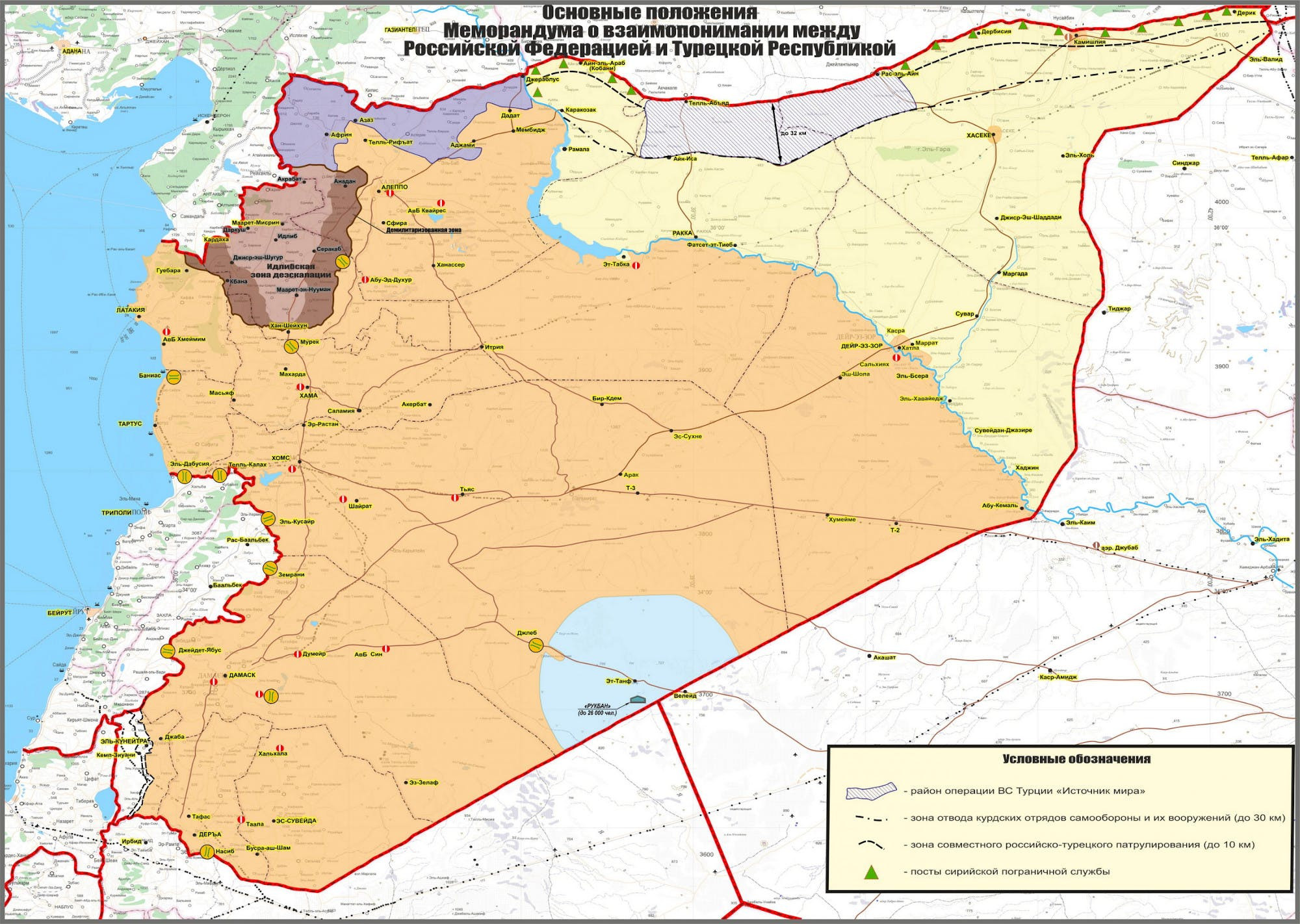

This was clear when Turkey launched its intervention into northern Syria in October 2019 that was aimed primarily at U.S.-backed predominantly Kurdish local forces. That military operation was followed soon thereafter with a deal between Ankara and Moscow about patrolling that part of the country.

Ergodan had already incited the ire of the United States and had drawn criticism from other NATO allies by insisting on buying S-400 surface-to-air missile systems from Russia. The U.S. government subsequently booted Turkey out of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program over operational security concerns, which you can read about more in these past

War Zone

pieces. Turkey has remained defiant, announcing plans to buy more S-400s and other Russian military hardware, which, in turn, looks set to result in serious U.S. sanctions and a potential arms embargo.

If the United States does take those actions, Turkey has threatened to respond by suspending American access to various bases inside the country, including Incirlik Air Base, which, at least far as is known, still hosts dozens of B61 nuclear bombs, and Site K, a radar facility that supports U.S. ballistic missile defenses in the region.

There has been a flurry of U.S. Air Force traffic to and from Incirlik in recent days, including a visit by a C-17A transport aircraft from 62nd Airlift Wing at Joint Base Lewis–McChord in Washington state. This unit has the so-called Prime Nuclear Airlift Force (PNAF) mission, making it responsible for air movements of nuclear weapons, which you can read about in detail in this past War Zone story. This followed an unusual sighting of another PNAF C-17A at Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands, another base where the United States keeps B61s.

It is unclear whether or not any of these movements indicate the withdrawal of any B61s, something the U.S. government has been reportedly considering doing since October, or other U.S. forces from Incirlik in response to recent U.S.-Turkish tensions.

Back in Libya, it’s unclear how the situation might continue to evolve in the coming days and weeks. As of yesterday, the LNA offensive toward Tripoli had appeared to stall as it had in April, which eventually led to Haftar’s forces withdrawing under international pressure.

If it looks as if Haftar and the LNA may finally be getting the upper hand, especially with backing from their various international partners, Turkey may feel compelled to intervene, which will only make the future of an already extremely complex conflict more uncertain and unpredictable.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com