The House of Representatives and the Senate have agreed to a version of an annual bill outlining defense policy and budgeting for the 2020 Fiscal Year that would stand up an all-new U.S. military service devoted to operations in space. After years of debate, Space Force now looks all but certain to formally arrive next year, but the language in the law that would create it shows that serious questions remain as to its organization and function. These issues, in turn, could hamper its ability to perform its missions at a time when threats to American interests outside of the Earth’s atmosphere are increasing and as U.S. military officials say they’re still trying to figure out what it will look like to “dogfight in space.”

Late on Dec. 9, 2019, the House Committee on Rules released a conference report detailing the outcomes of negotiations between the House and Senate on various provisions in their respective versions of the so-called National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2020. This includes a subsection, also referred to as the Space Force Act, which is devoted to the creation of the Space Force under the Department of the Air Force, as well as various other space-focused positions within the Air Force and the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

“I’ve been glowing for the last day,” Representative Mike Rogers, an Alabama Republican and one of the original proponents of a separate space branch within the U.S. military, had said at the Reagan National Defense Forum on Dec. 7, 2019. News had emerged the day before that members of the House had cut a deal to pave the way for Space Force in exchange for White House support for a separate provision regarding paid maternity leave for federal employees. President Donald Trump has been an outspoken supporter of Space Force for nearly two years now, as has Vice President Mike Pence.

“We have allowed China and Russia to become our peers, not our near peers and that’s unacceptable,” Representative Rogers added. “We have been doing some things short of the Space Force. I feel good but I will feel a lot better in about three or four years.”

Rogers and other Space Force advocates have long argued that the U.S. military needs a dedicated space-focused branch in order to adequately prioritize the defense of American interests in orbit. The Alabama congressman and others have said that the Air Force, which has historically managed the vast majority of military space research and development programs and acquisition efforts, cannot adequately perform this function given the demands of its terrestrial functions.

The current language in the Space Force Act aims to address these concerns and change the U.S. military’s relationship with space, as well as speed up developing and buying critical space-related systems, by transforming Air Force Space Command and its subordinate units, as well as potentially other elements from within the Air Force, into Space Force. The new Chief of Space Operations (CSO) will be a four-star general who sits on the Joint Chiefs of Staff and has the same standing as their colleagues from the Air Force, Army, Navy, and Marine Corps.

This arrangement fixed worrisome issues in a previous Space Force proposal that would have placed the head of the service under the direction of an Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for the Space Force, which would have put them at a bureaucratic disadvantage as the War Zone previously explained in detail. Under the new plan, the CSO will report directly to the Secretary of the Air Force, similar to how the Commandant of the Marines Corps reports to the Secretary of the Navy.

At least for the first year of Space Force’s existence, the CSO will be the same individual in charge of the recently re-activated U.S. Space Command (SPACECOM), not to be confused with Air Force Space Command. SPACECOM is a joint operational command that is responsible for overseeing and coordinating space-related activities across the U.S. military, which you can read about more in this past War Zone piece.

The Space Force Act would also lead to the establishment of a new Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy position within the Office of the Secretary of Defense, as well as new Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Space Acquisition and Integration and a Service Acquisition Executive of the Department of the Air Force for Space Systems and Programs roles within that service. These individuals would help further prioritize and advocate for space-related policy and spending.

They would also sit together with the Undersecretary of the Air Force, the CSO, commander of SPACECOM, and the director of the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), the U.S. Intelligence Community’s main satellite intelligence arm, on a new Space Force Acquisition Council to be coordinate and develop space-related acquisition requirements and policy.

“What we need is capability. We need assets in space, not a vast bureaucracy,” Secretary of the Air Force Barbara Barrett said alongside Representative Rogers at the Reagan National Defense Forum on Dec. 7. “We don’t need duplicate acquisition programs. We need to inspire people. People want to be associated with the Space Force. It’s a renewed excitement. We need to be moving quickly in acquisitions, we need efficient systems to get that done.”

Barrett is right about the need to increase emphasis on activities in space and Rogers isn’t wrong about the growing threats to American interests there, issues

The War Zone

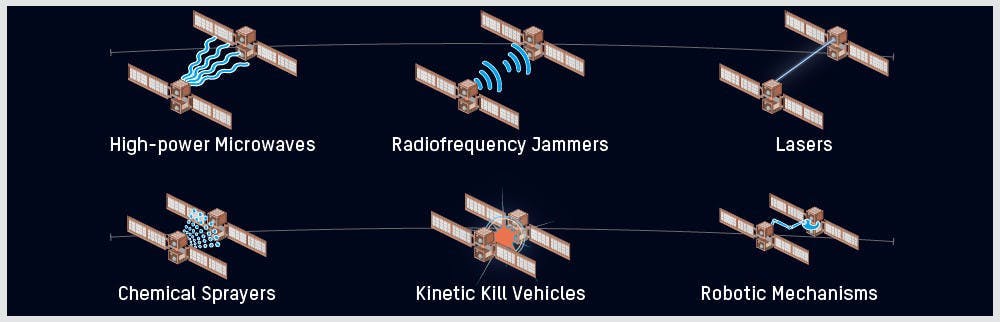

highlights on a regular basis. Space-based capabilities, including satellites handling early warning, intelligence gathering, communications, navigation, and more are absolutely essential to how the modern U.S. military operates every day. At the same time, potential adversaries, such as Russia and China, have been rapidly expanding their space-related activities, as well as developing means to counter the United States’ long-standing edge in satellite capabilities in this regard. This includes various anti-satellite weapons, including “killer satellites” and ground-based and air-launched interceptors, as well as non-kinetic systems to jam, spoof, or otherwise disrupt the operation of U.S. space-based systems. Other countries around the world are also beginning to take notice, including India, which demonstrated its own anti-satellite capability this year, and France, which plans to launch laser-armed mini-satellites to defend its assets in orbit.

Still, serious questions about how Space Force will operate, as well as how much it will cost, remain unanswered. The Space Force Act that members of the House and Senate have agreed to includes provisions asking for numerous reports detailing the service’s basic structure, function, and budget that would not be due until February, after Congress has already agreed to establish it.

This effectively means that lawmakers will be agreeing to buy Space Force sight unseen without any firm estimates about the resources it will need to do a job it has yet to fully define, setting up the very real potential for budget battles in the near future. The current version of the NDAA outlines a budget of just under $75.5 million for the service’s first year of operations, approximately two percent of what then-Secretary of the Air Force Heather Wilson said in 2018 would be necessary. Even then-Deputy Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan, who aggressively pushed back against Wilson’s figures, said that Space Force could need around $5 billion in total funding in its first five years.

“If she [Secretary Barrett] needs more, tell us and that’s our problem,” Representative Rogers stressed at the Reagan National Defense Forum, a position that ignores how fraught debates in Congress over increasing defense spending or reallocating existing funds are regularly. “We want the secretary to create the best Space Force the world has ever seen.”

Beyond the budgetary questions, there are major organizational issues that remain unresolved. As it stands now, the Air Force’s space elements will form the core of the new service. There is no plan to transfer the space-related assets under the control of the Army or the Navy to Space Force.

Though it’s true that Army and Navy space-related activities are much smaller than those present within the Air Force, the plan still means that Space Force will not have absolute control over the space “domain” and will have to coordinate, within Space Command, with the other services. Space Force also will not take control of space assets from the National Reconnaissance Office or other members of the Intelligence Community, such as the National Security Agency and Central Intelligence Agency. The existing Space Development Agency, Air Force Space Rapid Capabilities Office, and the Air Force Space and Missile Center, all of which charged with development and acquisition of space-related capabilities, are set to get placed be under the direction of the new Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Space Acquisition and Integration rather than Space Force.

All of this calls into question the true value of creating an entirely new service, which will live in the Department of the Air Force, and, at least foreseeable future, seems largely limited to roles and functions that that service is already performing. All told, despite years of studies and debate, both in public forums and behind closed doors, the Air Force, and the rest of the U.S. military, do not appear to have come to a clear understanding of how Space Force will actually work, despite its impending activation.

“There is a war room that has started to meet to work this out,” Barrett said at the Reagan National Defense Forum. “The whole team is very much devoted to the idea that this is a serious business and we have to get this done … We are going to get this as close to right from the beginning.”

“The central point is that we need a cadre of people who grow up and spend their whole careers learning and thinking: ‘how we dogfight in space,’” Air Force Major General Clinton Crosier, the Deputy to the service’s Deputy Chief of Staff for Strategy, Integration, and Requirements, said of Space Force at an event the RAND Corporation think tank held on Dec. 6, 2019. “Our adversaries have things on orbit that are looking at ways to do harm to our systems.”

Crosier’s comments speak to a larger and perhaps more pressing issue, that the U.S. military is still fundamentally unclear about what war in space might look like and how that fits with traditional notions of terrestrial conflict. In April 2019, former Secretary of the Air Force Wilson warned that the United States might have to demonstrate its resolve to respond to attacks in space, but it seemed apparent from her comments that the thresholds for such a response, and whether it would occur in orbit or down on Earth, remain worryingly unresolved.

This is made especially concerning when one considers the importance of space-based systems, including early warning and communications satellites, to the functioning of America’s nuclear deterrent. Attacks on these assets could leave the United States blind to subsequent strikes and hampered in its ability to launch its own counterstrikes, raising real questions about how the U.S. government might feel compelled to respond if it were to lose those assets. You can read more about these issues, which The War Zone has explored in-depth in the past, here.

At the Reagan National Defense Forum, Representative Rogers and Secretary Barrett had both called also called for greater declassification of U.S. space programs and capabilities. This could potentially offer greater insight into what options the U.S. military has right now with regards to conflicts in space and what kind of developments it is pursuing for the future. Declassifying intelligence on what potential adversaries, such as Russia and China, are doing could also give a better sense of existing and emerging threats.

“Declassifying some of what is currently held in secure vaults would be a good idea,” Barrett said. “You would have to be careful about what we declassify, but there is much more classified than what needs to be.”

“The lack of an understanding really does hurt us in doing things that we need to do in space,” Barrett continued. “There isn’t a constituency for space even though almost everyone uses space before their first cup of coffee in the morning.”

Right now, though, it seems hard to understand how Congress can be comfortable in ordering the creation of a Space Force without a clear understanding of its roles and missions, or what that will cost taxpayers, especially when the basic question of what a future conflict in space, or at least one involving hostile activities in that domain, looks like remains unanswered.

Space Force “has to be effective inside the national security environment from day one,” Air Force Lieutenant General David Thompson, Vice Commander of Air Force Space Command, who looks set to become the second in command of the new Space Force, said at the RAND event last week. “We have to create enough mass in the organization. We can’t worship efficiency if it means it’s going to create a struggle for this organization to integrate with the rest of the national security organizations.”

Right now, Congress looks to be about to create Space Force without a firm understanding of how it might fit into the larger U.S. national security apparatus, or having a sense of how much money it will need to set aside in future budgets to make that happen, let alone what it will take to address the potential struggles in doing so.

Contact the author: joe@thedrive.com