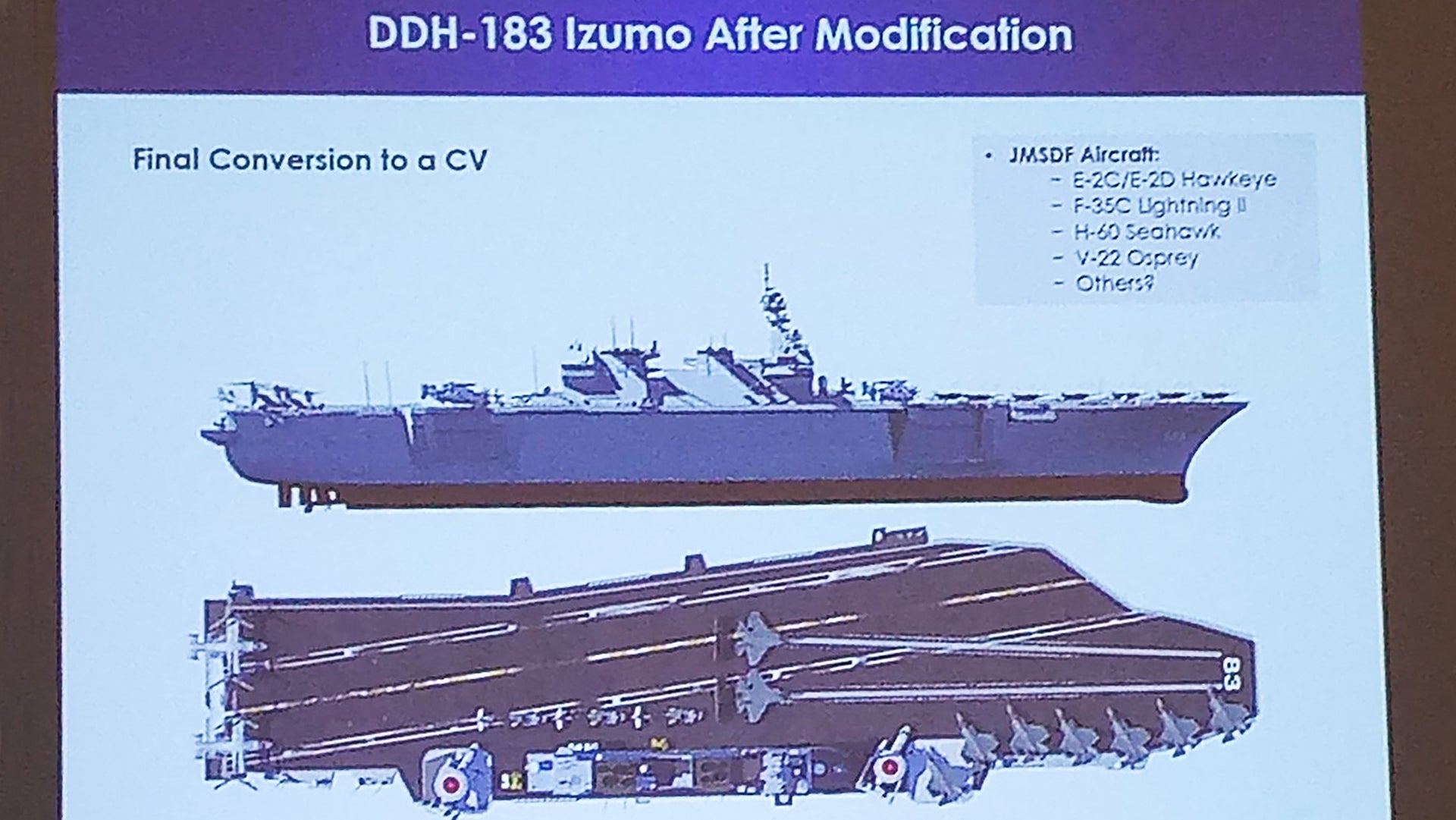

I have been bombarded with questions from readers today regarding a Powerpoint slide that has leaked depicting a drastically refitted Japanese Izumo class helicopter carrier with a pair of catapults and an angled landing area with arresting cables. In other words, the slide, which is from General Atomics, shows a Catapult Assisted Take-Off Barrier Arrested Recovery (CATOBAR) reimagining of Japan’s two largest warships. Then it was proclaimed by another site that Japan “has grand ambitions” to do this and buy the F-35C to pair with it. The problem here is that there is no actual evidence of this being the case. It’s recklessly uninformed at best, straight-up fantasy at worst.

The origin of the slide itself is important here—General Atomics. The privately-owned company does a ton of things in the scientific and defense fields, but they are probably best known for the Predator and Reaper lines of unmanned aircraft systems. They also happen to build the troubled, but one-day promising Electromagnetic Catapult System (EMALS) that will replace steam catapults on all U.S. Navy supercarriers going forward, as well as the Advanced Arresting Gear system that will do the same for recovering planes. Both systems are already installed on USS Gerald R. Ford.

In other words, no, General Atomics is not a ship designer, builder, or a complete ship systems integrator. So, this is very likely, if not absolutely some lighter concept art to pitch their catapult capabilities to Japan based on a theoretical design—a common tactic in the blue sky world of future defense capabilities discussions. There is a rendering for virtually everything.

The fact of the matter is that Japan is already buying 43 short-takeoff and vertical landing F-35Bs and is modifying its Izumo class carriers for this aircraft, specifically. This process has been made easier because, just as posited, the Japanese Ministry of Defense kept this possibility in mind when it originally ordered what are the country’s largest warfighting vessels since the end of World War II.

In the single slide we have, the modified Izumo class looks pretty cool as a conventional aircraft carrier, but the amount of work that would be required to realize such a conversion would be massive. In addition, although it seems that most people think slapping catapults and an angled flightdeck on an existing helicopter carrier is a relatively straightforward way of making a CATOBAR aircraft carrier, it’s not.

The added systems, mass, and huge changes in weight distribution that the ships were never designed for have snowballing impacts, regardless of cost. The vessels’ sea handling, speed, and fuel economy alone can be heavily impacted, and large parts of their interiors would have to be redesigned. That’s not saying it is impossible, but it makes little sense. Beyond that, the design shown in the slide is something of a nightmare for CATOBAR operations on multiple levels. A very limited amount of deck space and the inability to launch any aircraft while recoveries are underway are just a couple issues that are glaringly apparent.

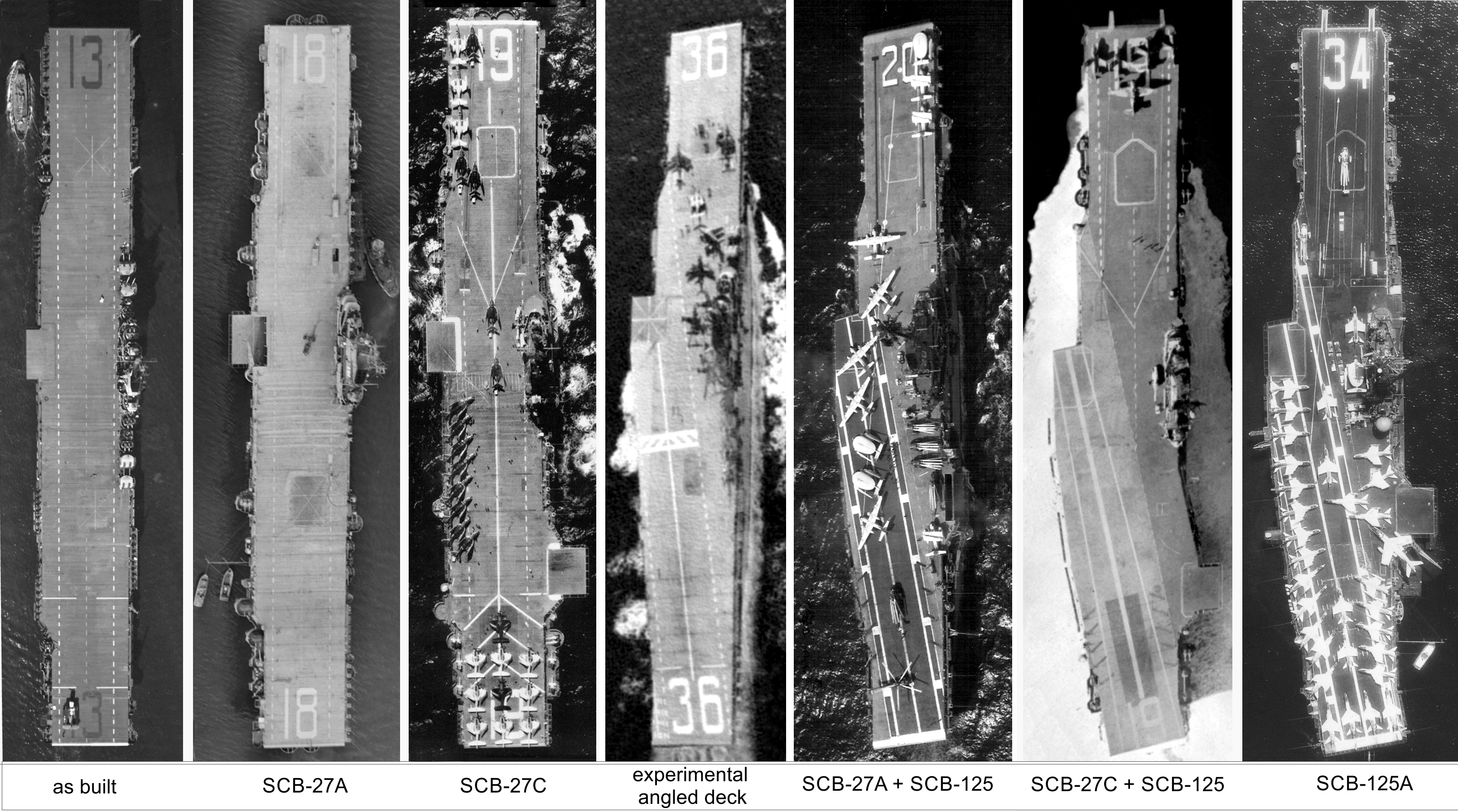

The Essex class from World War II is probably the best example of a relatively straight-forward flattop being turned into a post-WWII-era jet-capable carrier, but that was also a major undertaking and those ships were already designed as fixed-wing carriers. More so, in an era where the F-35B is available, an aircraft capable of ‘first day of war‘ operations alongside its A and C variant cousins, such an intricate and risky project has small advantages for this size of ship. Even the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps are still learning just how much combat capability they can squeeze out of their own similar amphibious assault ships with a heavy contingent of F-35Bs embarked.

If Japan really wanted to go with a conventional carrier design, then it would be best off just building those ships specifically for the task, not tearing apart the helicopter carriers they already have that were already designed with the F-35B in mind. But once again, there is no great reason for this nor is it anything but a hypothetical drawing as far as well know, and Japan has never shown interest in such an undertaking or footing the bill for introducing a CATOBAR capability into its force structure in the first place.

So, fun picture. We can always dream. But unless there is a whole story we don’t know, this image is little more than a common marketing exercise, and no, Japan has no intention of executing such a vision.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com