Satellite imagery that The War Zone has exclusively obtained calls into question the scale, scope, and effectiveness of airstrikes the U.S. military carried out on its own key base in northern Syria. U.S. personnel had operated the facility alongside their predominantly Kurdish allies, the Syrian Democratic Forces, or SDF, up until being abruptly evacuated last week under very controversial orders.

The photos indicate that a substantial portion of U.S.-constructed structures at the site remain intact despite statements that the strikes were supposed to have degraded “the facility’s military usefulness.” This all comes amid the announcement of a Turkish-Russian agreement on a buffer zone along the Turkish-Syrian border and uncertainty over the future of the U.S. military’s presence in the country as a whole.

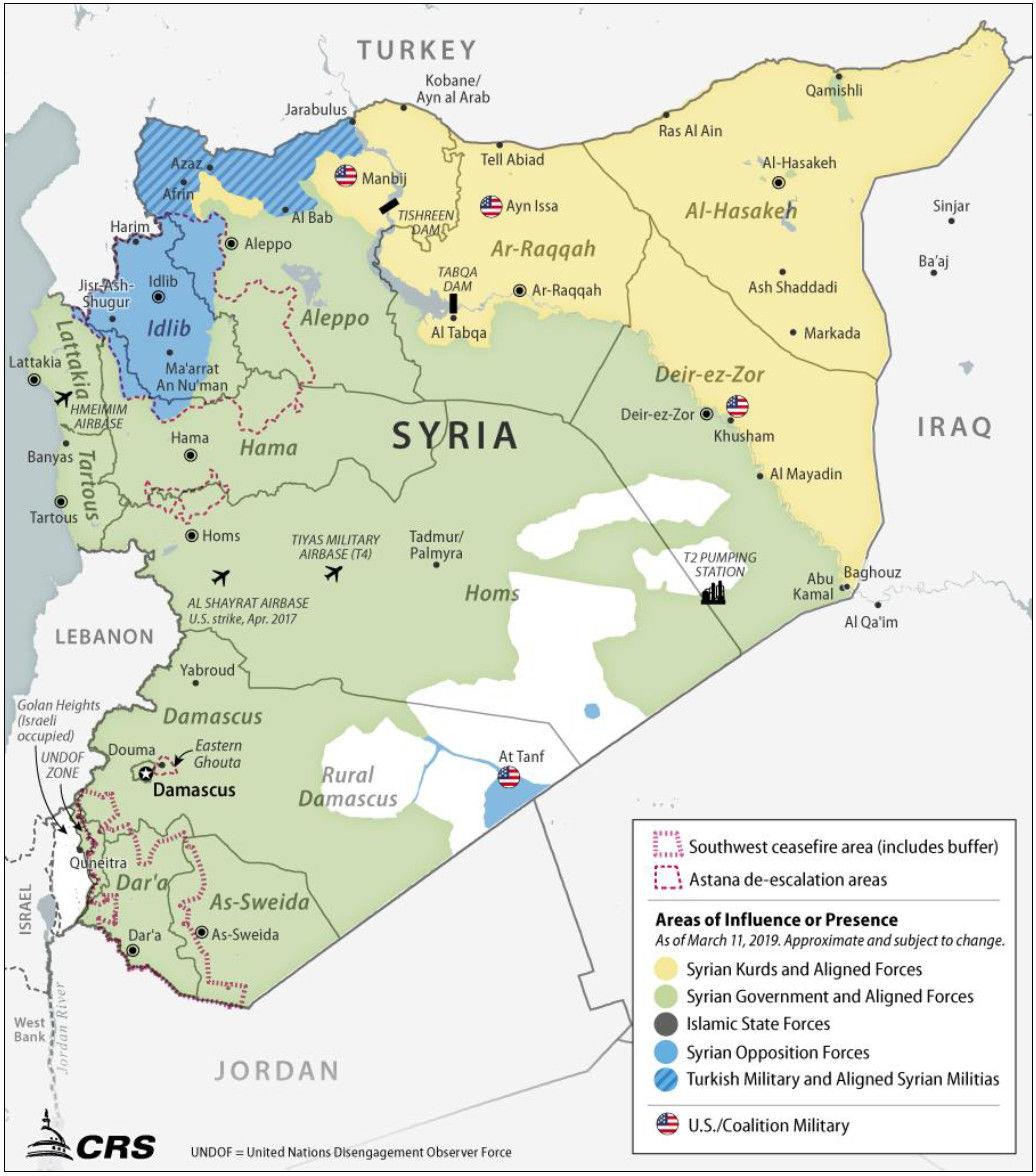

The U.S. military publicly announced that a pair of U.S. Air Force F-15E Strike Eagles had struck the now-defunct Lafarge Cement Factory in northern Syria, on Oct 16, 2019. This facility sits along the highly strategic M4 highway between the cities of Ain Issa and Kobane, also written Kobani, and had served as the “headquarters of the de facto Defeat-ISIS coalition in Syria,” U.S. Army Colonel Myles Caggins, the chief spokesperson for the U.S.-led coalition fighting ISIS in Syria and Iraq, said on Oct. 15, 2019.

The United States has been hastily pulling troops out of cities across northeastern Syria in increasing numbers after Turkey launched its own incursion into the region, dubbed Operation Peace Spring, ostensibly targeting the SDF, in cooperation with the Turkish-backed Free Syrian Army (TFSA), on Oct. 9, 2019.

The strikes only occurred “after all Coalition personnel and essential tactical equipment departed” the site, Caggins had stressed in a Tweet on Oct. 16, 2019. “As Turkish-backed militias advanced towards the Lafarge Cement Factory, between Kobani and Ain Issa, on Tuesday, Oct. 15, the SDF set fire to, then vacated, its facilities and equipment,” the colonel had explained to Foreign Policy‘s Lara Seligman the day before.

“We want to be very deliberate and very safe as we go about it,” U.S. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper had told reporters on Oct. 19, 2019, in reference to the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Syria. “Job number one, though, remains [the] protection of our forces.”

Satellite imagery that The War Zone obtained of the site as it existed on Oct. 12 and then how it appeared on Oct. 22, after the withdrawal and subsequent strikes, seem to tell a different story about just how useful the installation may remain now.

The U.S.-led coalition’s official statement only identified “an ammunition cache” as one intended target of the Oct. 16 strikes, but there is clear damage to at least two distinct buildings. One smaller structure is almost entirely destroyed and there is significant damage to another. It is not clear if the F-15Es struck these buildings or if personnel on the ground may have demolished them. We also don’t know if the structures held ammunition or if they housed other assets or had been serving in another role, such as acting as a command center.

There is evidence of another possible strike on or demolition of a set of small structures to the immediate southwest of the damaged buildings, as well. This does not appear to have been the area that SDF forces had burned on Oct. 15, which is further to the southwest, meaning that coalition forces would have been responsible for destroying any assets at this particular location, as well. This could have been the ammunition depot mentioned by the coalition spokesperson, we just don’t know at this time.

Both of the damaged buildings predate the U.S. ground intervention into Syria, though the smaller one appears to have received some additions on the left side since American personnel arrived. Lafarge’s operations in the country also began before the beginning of the Syrian Civil War in 2011. Last year, a French court indicted the company over complicity with crimes against humanity and financing terrorists after years of investigations indicating that the firm had paid millions to ISIS to release hostages and leave the plant alone. The French government also intervened in 2014 to ensure that the U.S. military did not bomb the site on the grounds that it was still a functioning civilian enterprise.

It’s not surprising that U.S. and other coalition forces chose to occupy it and use it for their own purposes after beginning to move into the region in force circa 2015. The site was already relatively fortified and offered the high ground, providing great force protection and offering a unique opportunity to monitor surrounding areas over a great distance. It also had a number of large concrete pads that were readily convertible into helicopter operating areas, too.

Other satellite imagery from Oct. 15 had shown a large fire at a tertiary location just to the southwest of the main Lafarge plant, which is likely where SDF forces had their associated base of operations. As of Oct. 22, whatever this adjacent site had been was still smoldering a week after the blaze was spotted.

It’s impossible to tell from the imagery what the inside of the remaining structures might look like and what U.S. and other coalition forces removed before making a hasty retreat. The satellite images from Oct. 12 and Oct. 22 make clear that the base’s occupants had evacuated a substantial number of helicopters, vehicles, and other equipment, including entire shipping containers, before they left for good.

At the same time, the assertion that the subsequent airstrikes made a real impact to “reduce the facility’s military usefulness” is questionable at the very best. It certainly pales in comparison to other “terrain denial” strikes the U.S. military has carried out to deny opponents access to certain areas in the past.

It’s certainly valuable to deny any potential enemy forces access to any weapons and ammunition, but that doesn’t negate the value of the facilities there, which American forces substantially upgraded and expanded for military purposes. Days after all coalition and SDF forces had left the site, the vast majority of the facilities, seem to be intact.

Three clamshell hangars, ubiquitous features of U.S. military forward operating locations around the world, notably remain standing adjacent to an area that U.S. forces had turned into a heliport. Satellite imagery shows that these had supported U.S. Army UH-60 Black Hawk transport helicopters and AH-64 Apache gunships.

Special operations helicopters, such as those belonging to the Army’s elite 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment have made use of the site, as well. Various satellite images over the years clearly show the presence of shadowy Sikorsky S-92 helicopters, which have been seen supporting coalition special operators on multiple occasions.

Rows of structures, include large tents and shipping containers, which would have provided living space, mess halls, and other amenities to U.S. and coalition personnel at the site remain in place across the factory, the main boundaries of which are around a mile long from north to south and nearly a half a mile wide. While they may not offer the same quality of life as before, they certainly look habitable, at least from the air. Some regional journalists have already shot video inside the site, which shows fires burning in some buildings, but it is unclear if these were set before or after American personnel left or how widespread that damage might be. By every available indication, U.S. and other coalition forces left significant and potentially useful infrastructure behind.

This is in line with the American pullout from Manbij, further to the west, which occurred on Oct. 15. Russian private military contractors and media outlets had subsequently shot extensive video from inside the former U.S. base there, showing food and personal items still on tables in the mess hall, functional electrically-powered gates at entry control points, and more. This was a major propaganda coup on top of a very practical victory for the Kremlin and its Syrian regime allies.

The cement plant still clearly offers military utility, raising questions about who may now be able to exploit those remaining capabilities, both for practical and propaganda purposes. It seems unlikely that American or other coalition forces will return to the site any time soon, if ever. ISIS already claims to have sent fighters inside to investigate.

Leveling the entire installation may not be necessary or realistic, but certainly destroying whatever unfortified improvements exist and making the cement plant turned military headquarters into a far less turn-key facility for military operations seems highly logical.

On Oct. 22, 2019, Turkey and Russia also announced plans to establish a buffer zone along the full extent of the Turkish-Syrian border with both countries conducting patrols in certain areas. The deal also leverages a 1998 arrangement between Turkey and Syria to cooperate on fighting terrorists and separatists, which will enable Turkish forces to remain in the country indefinitely. Turkey views the Kurdish People’s Protection Units, also known as the YPG, which contributed the bulk of the manpower for the SDF, as terrorists. The YPG has less than a week to withdraw from the entire buffer zone or face a major offensive.

The U.S. military and the SDF have already withdrawn to the southeast from this buffer area. The Pentagon says that it still plans to pull out the bulk of American forces from the country in the coming weeks in line with a decision that U.S. President Donald Trump first announced in December 2018.

That plan, as it stands now, will also see American troops continue to operate a small garrison at At Tanf near Syria’s southern borders with Iraq and Jordan. The rest of the forces withdrawing from Syria have been flowing into Iraq and the Pentagon had said that these personnel would remain there to conduct cross-border operations against ISIS, if necessary. However, the Iraqi government has said that it has not given permission to its American counterparts to increase their force posture within its border that these personnel can only remain in the country “in transit” before they have to go somewhere else.

In addition, the Pentagon has now proposed retaining a similar base near the Syrian oil fields around the city of Deir Ez Zor, though it has not made a decision about whether or not to implement that plan. Without the stability that a larger U.S.-occupied zone in northeastern Syria affords and the logistical infrastructure there, it is unclear how viable such a forward outpost would be, even in the near term.

At the same time, a backlash to Turkey’s intervention in Congress, which had led to calls for an arms embargo and substantial sanctions, has been steadily dying down since the Trump Administration’s decision to largely acquiesce to Turkish demands with regards to the buffer zone along the border. Trump himself, who at one point vaguely threatened to “obliterate” Turkey’s economy if Operation Peace Spring did not proceed according to his liking, has repeatedly dismissed criticism of his handling of the situation, saying bluntly last week that “it’s not our problem.”

Senator Lindsey Graham, a Republican from South Carolina and a major Trump ally who had been among the harshest critics of Trump’s handling, has also notably changed his tone in recent days. “[I am] Increasingly optimistic that we can have some historic solutions in Syria that have eluded us for years, if we play our cards right,” Graham said in an interview on Oct. 20, 2019. However, opposition to the Trump Administration’s policies remain and some American legislators did recently issue a joint statement with various counterparts in Europe condemning Turkey’s actions in Syria.

The situation in Syria itself remains fluid and will likely continue to evolve in complex ways in the coming weeks and months as the U.S. proceeds with and finalizes its withdrawal plans. Unfortunately, Turkey’s intervention has already provided space for ISIS and other terrorist groups in Syria to reassert themselves and handed Syrian dictator Bashar Al Assad, together with his Russian and Iranian allies, major territorial gains.

On top of that, there have also been steady allegations of TFSA fighters committing atrocities and the Turkish operation has already prompted a major humanitarian crisis. There are very real concerns that the Turkish occupation of northern Syria could lead to ethnic cleansing across northeastern Syria, if it hasn’t already begun, and Turkey says it plans to resettle millions of Syrian Arab refugees into the zone, despite the continuing lack of security and basic infrastructure.

Ethnic Kurds, as well as other ethnic and religious minorities in northern Syria, the communities that provided the vast majority of the personnel for the SDF and who were instrumental in rolling back ISIS, feel betrayed and have openly protested the departure of American forces. As more American troops withdrew this week, some Syrian Kurds threw stones and tomatoes at U.S. vehicles, while others held signs lamenting their departure. Some Iraqi Kurds showed similar frustrations as those forces arrived in Erbil, the capital of Iraq’s semi-autonomous Kurdish region, which has been under de facto U.S. protection since the 1990s and where American troops have generally been treated with appreciation.

For the moment at least, the now-abandoned major operations outpost at the Lafarge Cement Factory has become something of a troubling monument to the ghost of America’s military operation in Syria that had been successfully churning along for years up until just days ago.

With so much of the base intact, it’s more likely than not that the new powerbroker in the very troubled region will set up shop there and use America’s investments in the facility for their own objectives, whatever they may end up being.

Author’s Note: We have updated this story to clarify that it is unclear which target or targets the F-15Es hit and about the prospects that coalition forces on the ground may have demolished more structures in the compound.

Contact the author: Tyler@thedrive.com